“The figure of the flâneur – the stroller, the passionate wanderer emblematic of nineteenth-century French literary culture -has always been essentially timeless; he removes himself from the world while he stands astride its heart,” Bijan Stephan writes at The Paris Review. In essays by the poet Charles Baudelaire and critic Walter Benjamin, the flâneur wanders dreamily through the fashionable modern city, taking in the sights and sounds – he (and it is always a he) is not a tourist, but a critic, an observer, a sophisticated appraiser, detachment embodied.

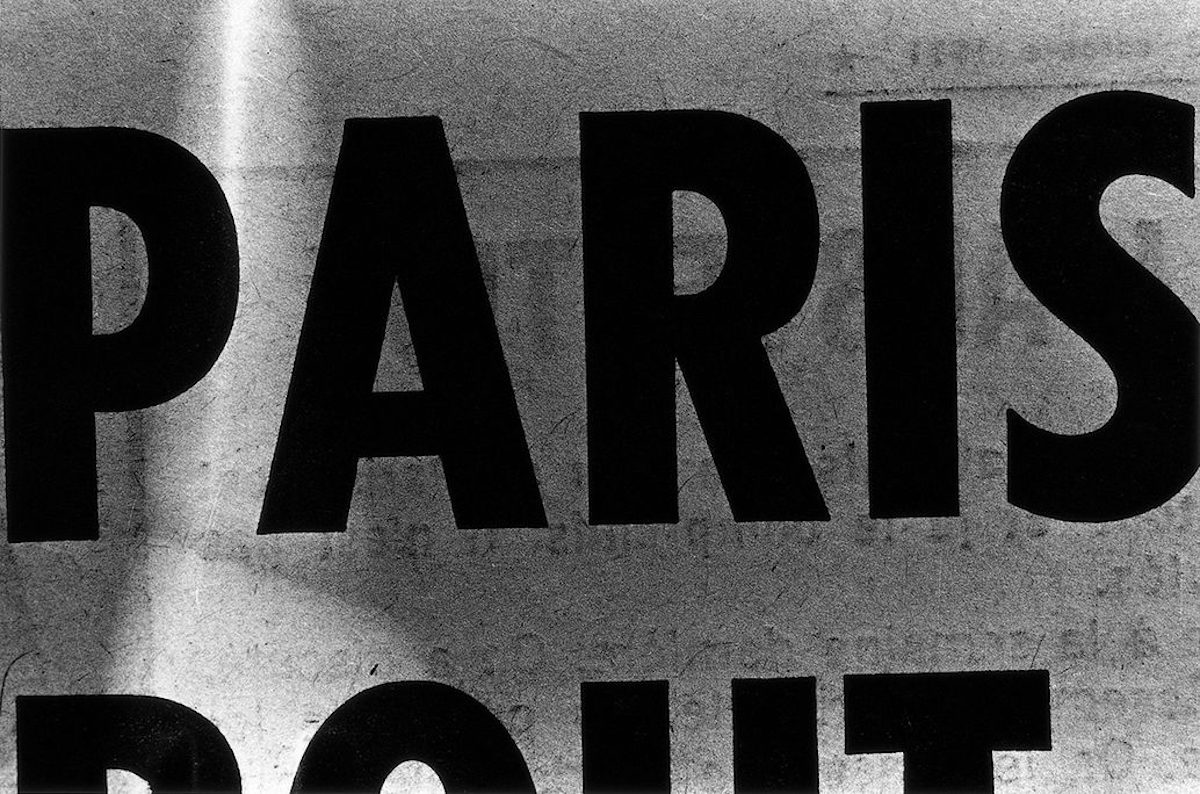

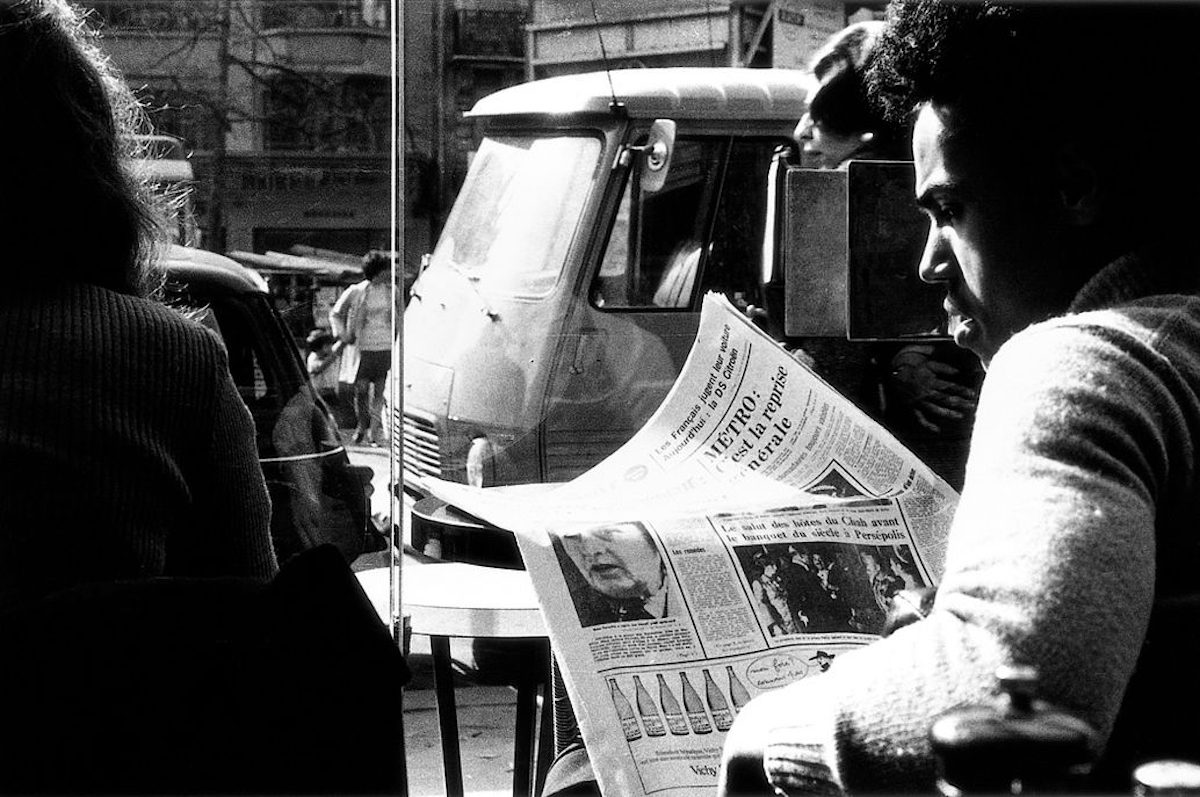

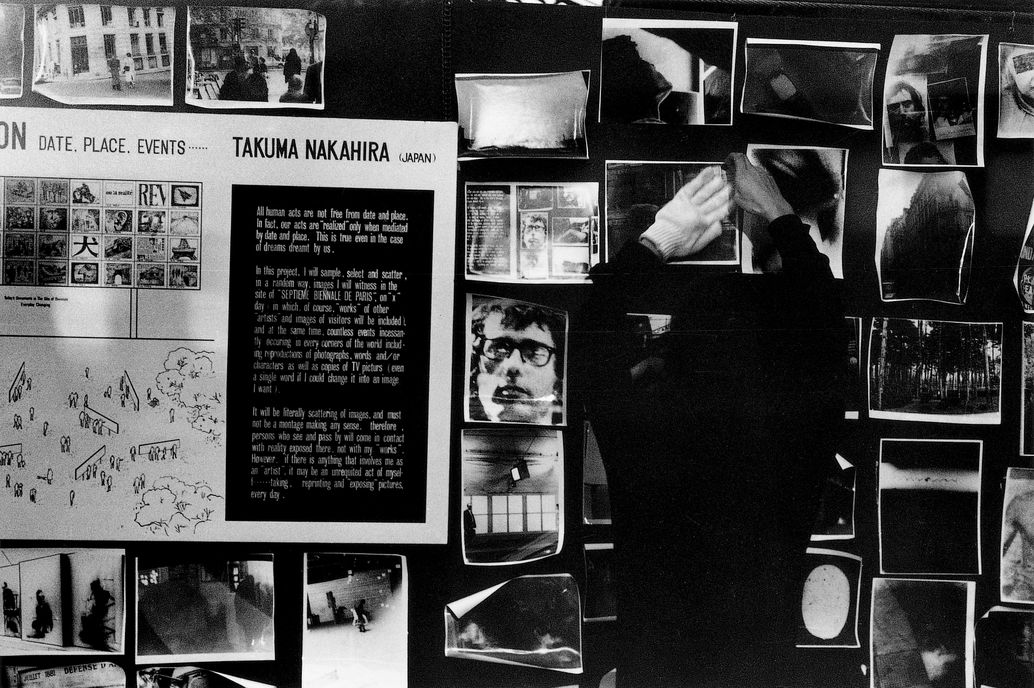

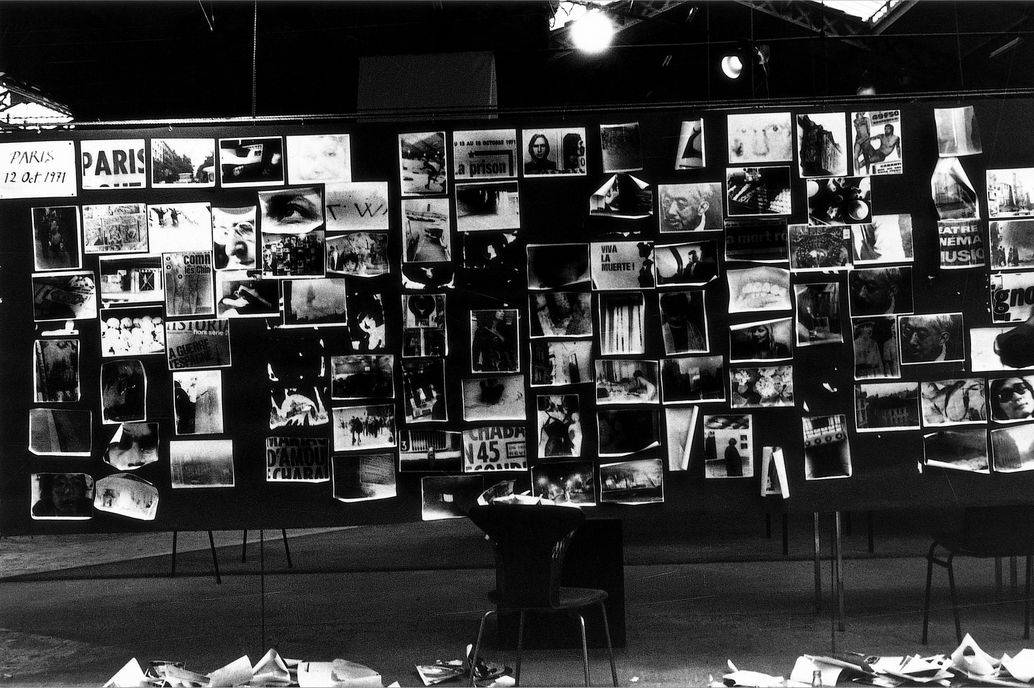

Contrast this figure with Takuma Nakahira’s fragmented 1971 vision of Paris in his series Circulation: Date, Place, Events, a photographic performance piece for the Seventh Paris Biennale that works as a kind of anti-flânerie, a postmodern pastiche of hastily composed snapshots. “The flâneur is a masculine figure, privileged, and an icon of leisure. The city, which he mapped with his walks, was a playground, the spectacle for his spectatorship,” write Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye. Nakahira, on the other hand, experienced the city as an almost violent sensory attack.

In a 1977 essay on the photographer Eugene Atget, Nakahira describes a “constant sensory abnormality that was brought about as a result of my habitual use of sleeping pills, which I had been taking for insomnia. It is difficult to briefly describe the hallucinations I had at the time. I call them hallucinations, yet it was not that I was having visions of something that was not there. This condition was instead the disintegration of this sense of distance, the loss of the balance that maintains the relationships between material reality and myself.”

In his Circulation series, Nakahira seems to recreate this disorienting and painful experience, “to photograph, develop, and exhibit,” he said, “nothing but the Paris that I was living and experiencing.” The Japanese photographer would take photos during the day, develop them at night, and “paste his sometimes-wet photographs up in the morning,” Dan Abbe writes at Popular Photography. “As the exhibition went on, his allotted space became more and more cramped, and the photographs eventually spilled out onto the floor.”

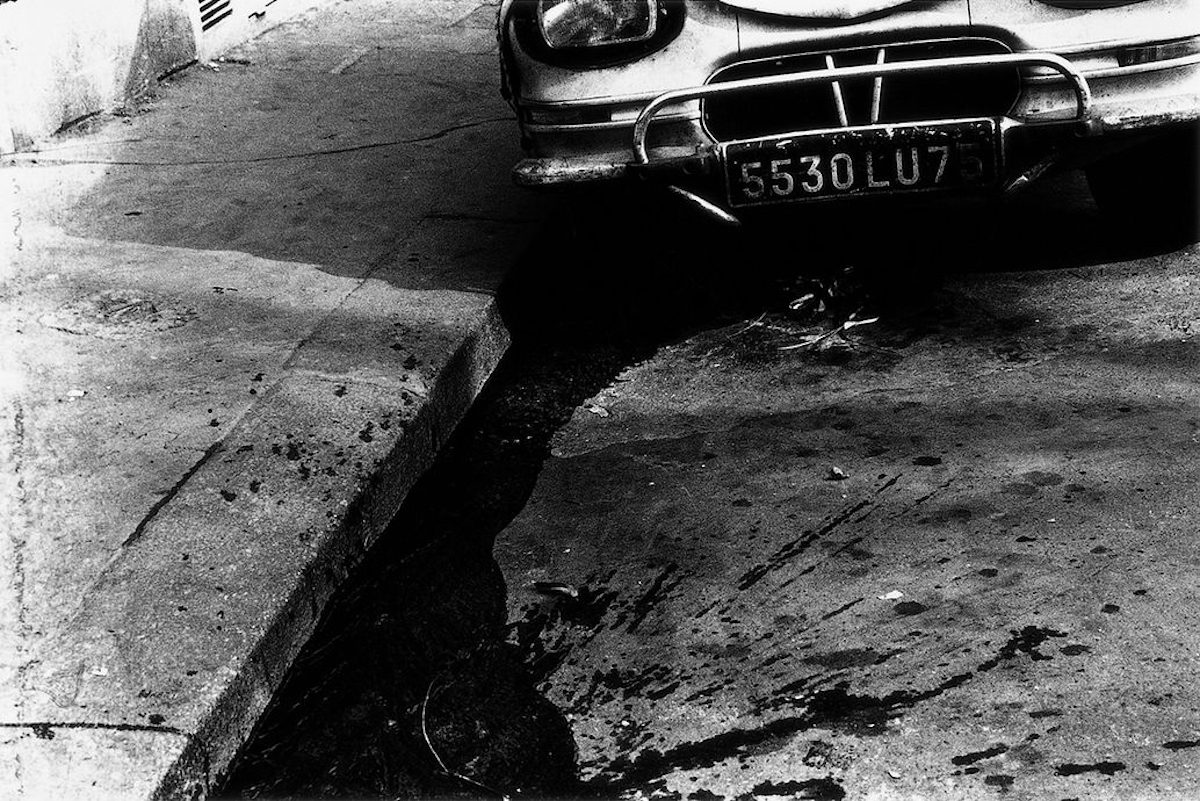

The Paris that emerges is not the monumental city of lights, but a disconnected succession of sudden impressions, often obscured and indistinct, a feature of the “blurry-grainy-out of focus” style of the artists associated with short-lived but influential Japanese photo magazine Provoke. It is a city of objects, where people appear almost as if by accident. Nakahira’s method emerged from his theoretical refinement as a writer as well as from his years of photographic experimentation. The question he asks in his essay on Atget is this: “What is seeing exactly?”

As if in answer, Circulation illustrates what it is like to see the city from the vantage of a “sick person,” someone who seems to lurch through the city, fleeing the terror of annihilation.

If I was at a café talking with a friend, I would suddenly notice that there was a glass on the table. In that instant, I could not ascertain the distance between the glass and myself. As a result, I was unable to recognize the glass as a glass. Once seized by the attack, I became seemingly immobilized with terror, and although at the time I completely lost the composure to be able to analyze indifferently what was happening, later I would look back and realize that this was exactly what was happening.

Looking out at the scenery beyond a train window, suddenly material reality would come at me and directly pierce my eyes. In order to protect myself within the train car speeding on, (the anxiety that I was unable to control myself and would leap out the window was very strong), I had to close my eyes and tightly clutch the armrest. Under this kind of sensory abnormality, I firmly believed that consciousness was a mass of scar tissue from the wounds inflicted by material things directly upon my eyes or my retina. For seeing material things meant that they would directly stab into my eyes. No longer able to go out and walk the streets, I was thus hospitalized. It’s not as though this anxiety has been eliminated, for even now my consciousness is taken over by that of a sick person’s. Therefore, isn’t “seeing” exactly the act described by the reversed expression, “material reality would come at me stabbing?”

Nakahira describes these disturbing psychological events almost apologetically: “All this will be a bit personal.” He offers the account, however, in service of a larger theoretical question that came to haunt the consciousness of postmodernity as it confronts the loss of fixed identities. “I understand the fact that seeing is to possess and give meaning to the world according to the process of establishing a secured distance between myself and the subject,” he writes, articulating the detachment of the flâneur. “But what happens if this distance disintegrates?” Circulation: Date, Place, Events immerses the eye fully in the onrushing materiality of the city.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.