Nothing thrills the masses like space travel.

A few names epitomise the mid 20th Century space race. One of them is Alan Bartlett “Al” Shepard, Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998). Alan B Shepard was the first American in space. And it was huge deal because the flight was broadcast on the TV.

When on May 5, 1961, Alan B Shepard was strapped into the the Freedom 7 spacecraft, millions tuned in. He was launched by one of former Nazi Werner Von Braun’s Redstone rockets on a ballistic trajectory suborbital flight.

He was cool. As delays took hold – and his space suit filled with his own urine – he told Mission Control: “I’ve been in here more than three hours. I’m a hell of a lot cooler than you guys. Why don’t you just fix your little problem and light this candle?”

Bang!

He rose to an altitude of 116 statute miles.

Around 15 minutes later, he landed in the Atlantic Ocean.

Alive.

Three weeks before that flight, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first man to fly into space.

…37-year-old Cdr Shepard of the US Navy was launched into sub-orbital flight from Cape Canaveral in Florida in a Mercury 3 capsule attached to a Redstone rocket. He travelled 115 miles into space and landed in the Atlantic just 15 minutes later. His first words after he was picked up by a helicopter were: “Boy, what a ride!” President Kennedy telephoned to congratulate the astronaut a few minutes after he was flown to aircraft carrier Lake Champlain.

In a veiled reference to last month’s achievement by the USSR’s space programme, the president said: “This is an historic milestone in our own exploration into space. But America still needs to work with the utmost speed and vigour in the further development of our space programme.”

During the flight, Cdr Shepard maintained constant communication with ground control. He opened his periscope, reported on cloud cover over Florida and North Carolina and commented, “Oh, what a beautiful view.”

As he re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere, the experienced test pilot was subjected to 11 times the force of gravity and travelled at 5,100mph but managed to report that he was “OK”.

The space capsule, which appears undamaged except for some heat scars, is being returned to Cape Canaveral for examination.

In this photo taken Sept. 25, 1959 in San Diego, California, U.S. astronauts laugh while standing around models of the Atlas and nose capsule designed to carry them into space. From left are Walter Schirra, J.R. Dempsey, executive of Convair, maker of Atlas, John H. Glenn, Jr., Virgil I. Grissom, Alan Shepard, Leroy G. Cooper Jr. and Malcolm S. Carpenter. RR Auction of Amherst, N.H. is auctioning off a letter Grissom wrote to his mother, how he and five of his fellow Mercury 7 astronauts resented John Glenn for getting the nod to be the first American to orbit the earth. (AP Photo/FILE)

Ref #: PA.18266821

Astronauts during survival training in the Mohave desert in an undated photo. From Left to right are L. Gordon Cooper, M. Scott Carpenter, John H. Glenn, Jr., Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Virgil I Grissom, Walter M. Shirra and Donald K. Slayton. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8611688

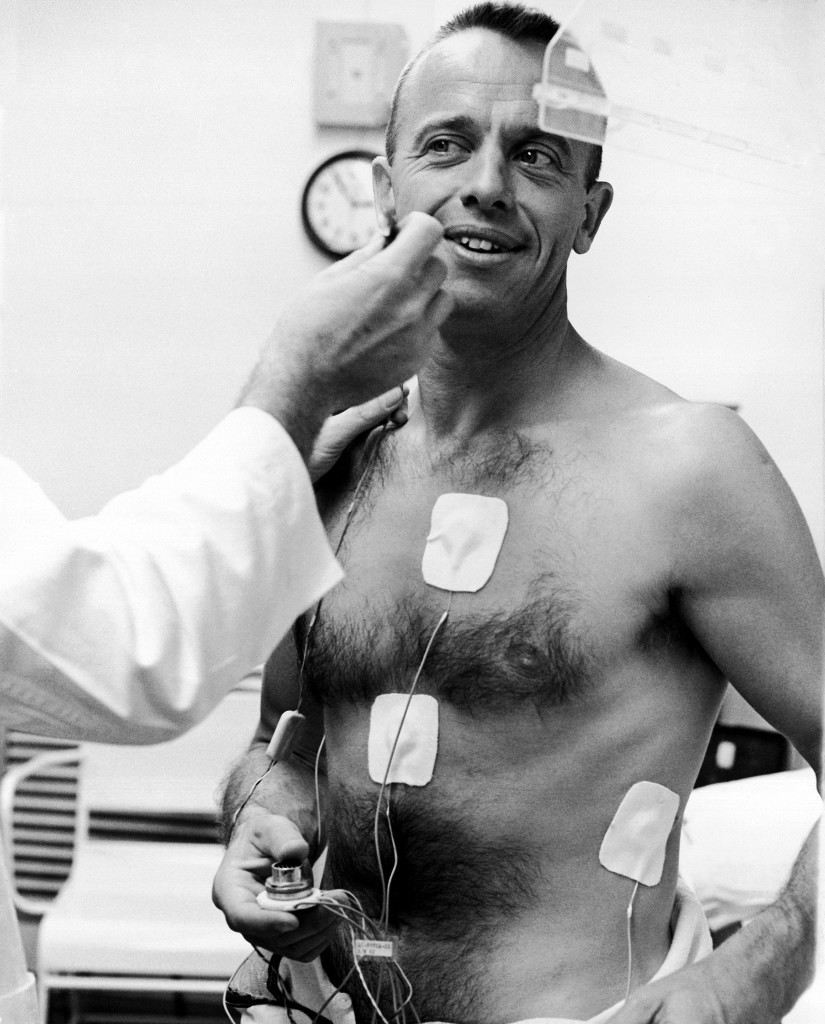

Alan B. Shepard, Jr., was in a light mood as he underwent final physical examination at his Cape Canaveral quarters for his manned space flight, May 5, 1961. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8611841A nurse serves breakfast for Astronaut Alan B. Shepard, Jr., left in his special quarters at Cape Canaveral, May 5, 1961 before he was suited for his space flight. At right is John H. Glenn, Jr., backup pilot for the manned flight. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8611835A thermometer in his mouth, Alan B. Shepard, Jr., watches as the astronauts? personal physician, Lt. Col. William K. Douglas, checks his blood pressure in Cape Canaveral, May 5, 1961. Shepard and his backup pilot, John H. Glenn, Jr., were given final physical examinations this morning at Cape Canaveral before Shepard took off on America?s first manned space flight. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8611817

Date: 05/05/1961

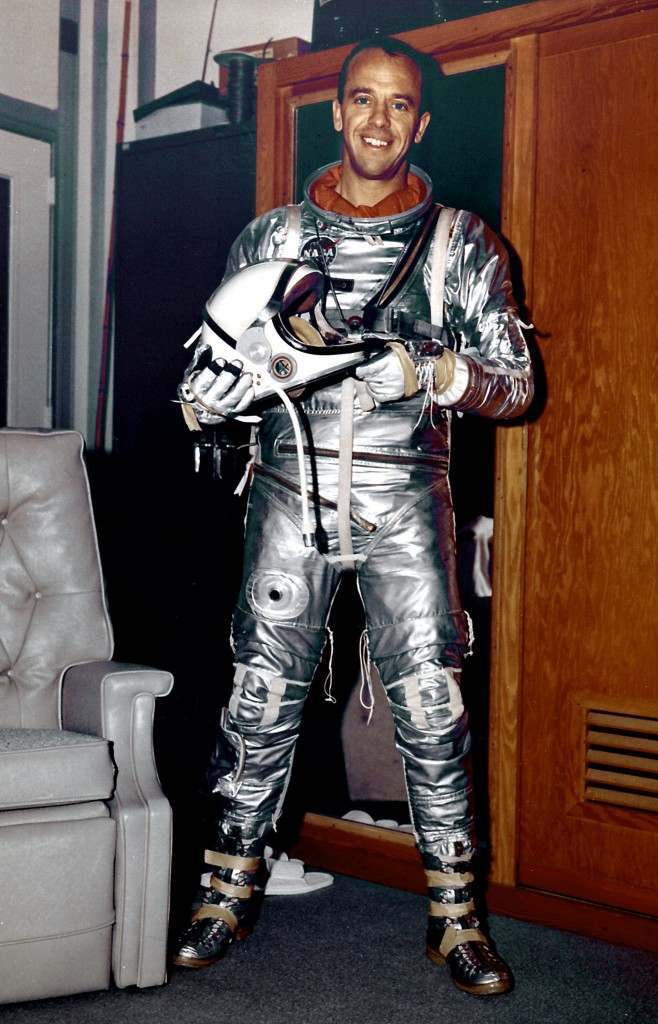

In his silver space suit, Alan B. Shepard, Jr., strides from the van as he arrives at the launching pad May 5, 1961 space flight from the cape. Towering in the background is the rocket which took Shepard on this country’s first manned space flight. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8628364

NASA Astronaut Alan Shepard Jr., is assisted into the Project Mercury spacecraft by his backup John H. Glen Jr., May 10, 1961. Astronaut Shepard made the first Project Mercury suborbital space flight and attained a speed of 5,100 miles per hour. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8566479

…once I learned the name Alan Shepard I treasured it, in part because he spelled his first name just as I spelled mine, and in part because hardly anyone else seemed to know who he was. This seemed very odd to me: Shouldn’t The First American in Space be a title of great honor? It was only years later, when I read Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, that I came to understand the complex national pathologies — the multi-front competition with the Soviet Union, the problem of knowing who your celebrated gladiators might be as long as your war stays Cold — that had produced the idolization of Glenn and the (comparative) marginalization of Shepard.\

Carrier Lake Champlain crew member shakes hand of Alan B. Shepard, Jr., alighting from helicopter aboard the carrier after his space flight from Cape Canaveral, Fla.Shepard was picked up at sea by the helicopter and taken to the carrier. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8611828

Almost beside herself with glee, Mrs. Alan Shepard, left, wife of famous astronaut, as she appeared on the front porch of her Virginia Beach home after the word had come that her husband was safe. With her are her mother and father, Mr. and Mrs. Russell Brewer, Alice Williams, a niece and her daughter Juliana in Norfolk on May 5, 1961. (AP Photo/Bill Allen)

Ref #: PA.8776619

Pioneering Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard and his wife Louise Shepard, sit in a car as they leave the White House May 8, 1961 after Shepard was presented with the NASA distinguished service medal by President Kennedy. In the car with the Shepards is Vice President Johnson. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.4932854

Navy Cmdr. Alan Shepard and his wife pose with Vice President Lyndon Johnson as they leave the White House for the Capitol in Washington on May 8, 1961. Approximately 250,000 persons lined downtown Washington streets to pay tribute to Shepard, first American to make a space flight. At the Capitol, Shepard and other astronauts were greeted by members of Congress. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8776607

Astronaut Alan Shepard, the United States first spaceman, waves to crowds lining 15th Street as he sits with his wife iLouise in an open car during a parade from the White House to the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington on May 8, 1961. Other U.S. Astronauts follow in the parade. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8776608

Mrs. Louise Shepard, wife of the first U.S. astronaut to make a space flight,Alan Shepard admires the NASA Distinguished Service Medal given Shepard by President Kennedy as Washington honored the spaceman. The couple poses at foot of ramp to plane at Andrews Air Force Base, Md. on May 8, 1961 taking them to Kangley Field, Virginia. (AP Photo/Paul Vathis)

Ref #: PA.8776626

Cmdr. Alan Shepard Jr., AmericaÂs first astronaut, kisses Mrs. Shepard upon his arrival at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington on May 8, 1961. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8776629

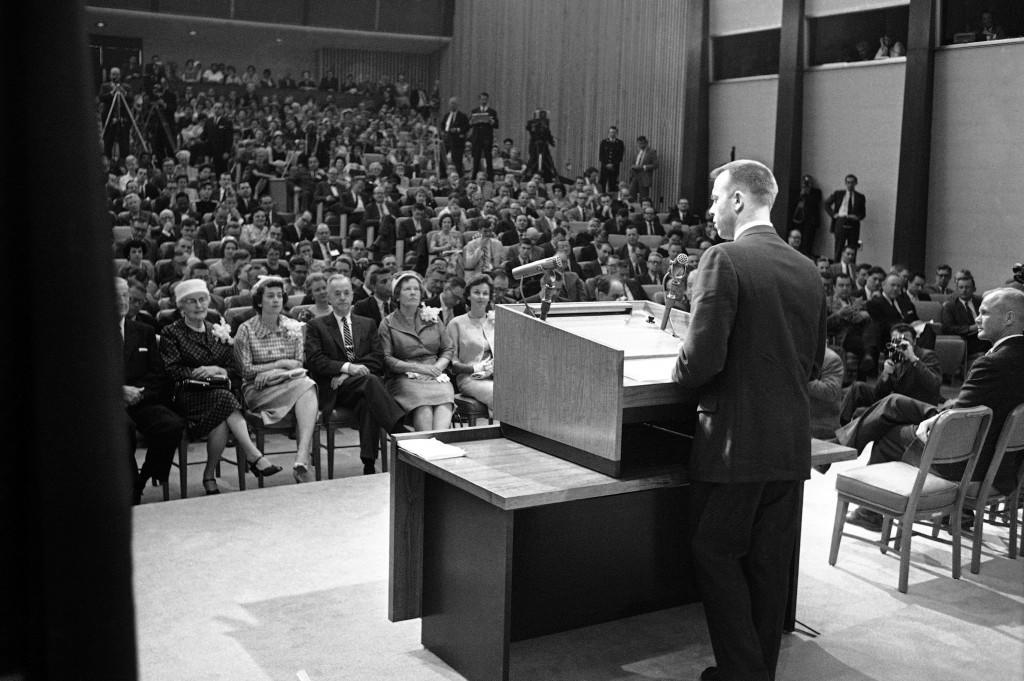

AmericaÂs first spaceman, Navy Comdr. Alan Shepard, appears in a crowded state Department auditorium at news conference on May 8, 1961. Sitting in the front row, from left, are: Mr. and Mrs. R. P. Brewer, parents of Mrs. Shepard; Col. and Mrs. Gordon Sherman, sister of Astronaut Shepard; Col. and Mrs. Alan Shepard, Sr., and Mrs.Louise Shepard, wife of the Astronaut. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8776615

Astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., the first American to make a space flight, relaxes beside a pool at a Cocoa Beach Hotel in Cape Canaveral, Florida on July 16, 1961. Mrs. Louise Shepard reads a book in the background. This week a second astronaut will duplicate ShepardÂs feat by making a suborbital flight from Cape Canaveral aboard a Mercury spacecraft atop a Redstone rocket. (AP Photo/Murray Becker

Ref #: PA.8776659

Woolf set the tone of what had gone:

Even in California, where it was very early, highway patrolmen reported a strange and troubling sight. For no apparent reason drivers, hordes of them, were pulling off the highways and stopping on the shoulders, as if controlled by Mars. The patrolmen were slow in figuring it out, because they did not have AM radios. But the citizenry did, and they had become so excited as the countdown progressed at Cape Canaveral, so ravenously curious as to what would happen to the mortal hide of Alan Shepard when they fired the rocket, it was too much. Even the simple act of driving overloaded the nervous system. They stopped; they turned up the volume; they were transfixed by the prospect of the lonely volunteer about to be exploded into hash.

This tiny lad, up on the tip of that enormous white bullet, appeared to have about one chance in ten of living through it. Over the three weeks since the great Soviet triumph of Gagarin’s flight, one terrible event had followed another. The United States had sent in a puppet army of Cuban exiles to conquer the Soviets’ puppet regime in Cuba, and instead suffered the humiliation that became known as the Bay of Pigs. This had nothing directly to do with the space flight, of course, but it heightened the feeling that this was not the time to be trying brave and desperate deeds in the contest with the Soviets. The sad truth was, our boys always botch it. Eight days after that, on April 25, NASA had another big test of an Atlas rocket. It was supposed to carry a dummy astronaut into orbit, but it went off course and had to be blown up by remote control after forty seconds. The explosion nearly wiped out Gus Grissom, who was following the rocket’s ascent as chase pilot in an F-106. Three days after that, April 28, a so-called Little Joe rocket with a Mercury capsule on top of it went off on another crazy trajectory and had to be aborted after thirty-three seconds. Both of these were tests of the Mercury-Atlas system, which would be used for orbital flights, and they had nothing to do with the Mercury-Redstone system, which Shepard would be riding—but it was far too late to make fine points. Our rockets always blow up and our boys always botch it.

………

His face was pointed straight up toward the sky, but he couldn’t see it because he had no window. All he had were two little portholes, one on either side, above his head. The true pilot’s window and hatch wouldn’t be ready until the second Mercury flight. He might as well have been inside a box. A greenish fluorescent light filled the capsule. He could see outside only through the periscope window on the panel in front of him. The window was round, about a foot in diameter, in the middle of the panel. Outside, in the dark, the launch crewmen on the gantry could see the lens of the periscope if he pointed it their way. They kept walking in front of it and giving him big grins. Their faces filled the window. There was a wide-angle distortion, so that their noses protruded about eight feet out in front of their ears. When they grinned, they seemed to have more teeth than a perch. Once the dawn broke he could look out of the periscope and turn it this way and that, and see the Atlantic over here… and some people down on the ground… although the perspectives were a bit strange, because he was lying on his back and the periscope window was not terribly big and the angles were unusual. But then the sun grew brighter and brighter and he kept getting bursts of sunlight in the periscope window, lying on his back like this and looking up, and so he reached up with his left hand and clicked a gray filter into place. That helped a great deal, even though it neutralized most colors. Now that the hatch had been bolted shut, Shepard could hear practically nothing from the outside world except the voices that came over the headset inside his helmet.

?Freedom 7?, the capsule Commander Alan B. Shepard rode into space, is unloaded from a ?Globemaster? plane at Rome?s Ciampino airport, June 10, 1961. The capsule will be displayed at the American exhibit at the International Electronic and Nuclear Fair, which will open on June 13, at the Universal Exposition complex in Rome. (AP Photo/Mario Torrisi)

Ref #: PA.8611645

Shown in Dallas on Monday, March 24, 2008 is a scoop used by Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell to pick up moon dust on the Apollo 14 mission. It is one of the items included in the Heritage Auction Galleries, Air and Space Auction, Tuesday, at the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas. (AP Photo/Donna McWilliam)

Ref #: PA.5802540

He’d journey into space again aboard Apollo 14 between January 31 and February 9, 1971. In the compnay of Stuart A. Roosa, command module pilot, and Edgar D. Mitchell, lunar module pilot. Maneuvering their lunar module, he trod on the moon – and played golf.

Workmen look on as the USNS Alan Shepard slides into the water as the ship is launched at the General Dynamics NASSCO shipyard Wednesday, Dec. 6, 2006 in San Diego. The USNS Alan Shepard, named in honor of the NASA astronaut, is the third ship of an expected class of 11 T-AKE dry cargo-ammunition ships to be built by General Dynamics NASSCO for the U.S. Navy. (AP Photo/Denis Poroy)

Ref #: PA.4208336

Astronaut Alan B. Shepard stands with the American Flag on Lunar Surface in February 1971. Shepard was the first American to fly in space and the fifth human to walk on the moon. This particular mission was Apollo 14 which launched Jan. 31, 1971, and returned Feb. 9, 1971 after having spent 33 1/2 hours on the surface. (AP Photo/NASA)

Ref #: PA.8637936

Five astronauts wait in Washington on April 17, 1967 to testify before a House investigating subcommittee in the probe of the fire aboard the Apollo I which took the lives of three follow spacemen at Cape Kennedy, Fla. From left are Frank Borman, James A. McDivitt, Donald K. Slayton, Walter M. Schirra Jr., and Alan B. Shepard. (AP Photo/Bob Schutz)

Ref #: PA.9931229

Alan Shepard, in his space suit makes last minute preparations for his historic ride into space, June 14, 1963. (AP Photo)

Ref #: PA.8566500

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.