The history of auto design is filled with failed ideas and strange prototypes that never made it to the production line. In the wake of World War II especially, the industry kicked into high gear. Released from building tanks and munitions, large automakers like GM turned their focus back to giving consumers what they supposedly wanted most. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs like salesman Glenn Davis took advantage of the booming post-war economy to launch their own designs. “Davis’s timing could not have been better. Post-World War II America was ravenous for new cars,” writes Autoweek, “and the Davis publicity machine thrived in this consumer feeding frenzy.”

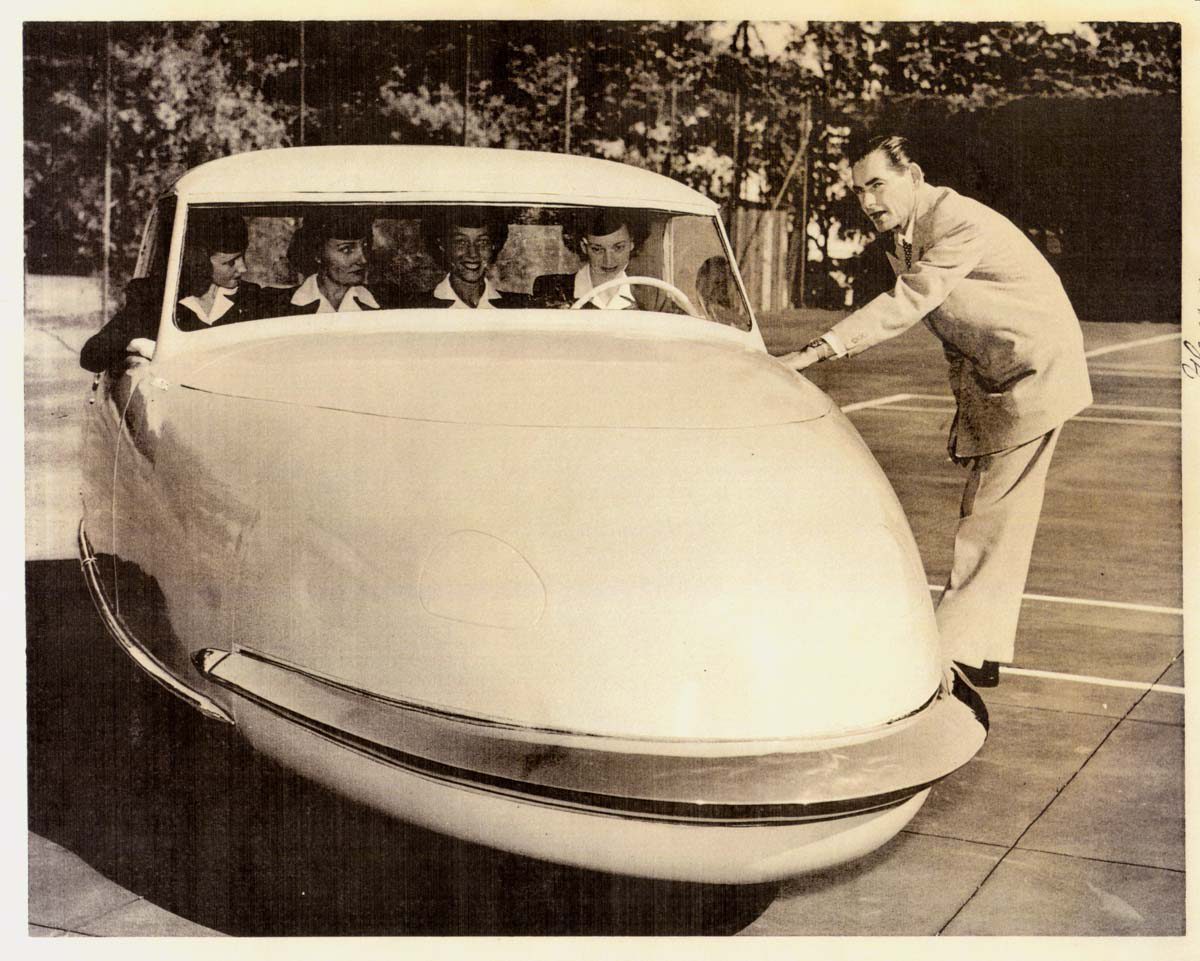

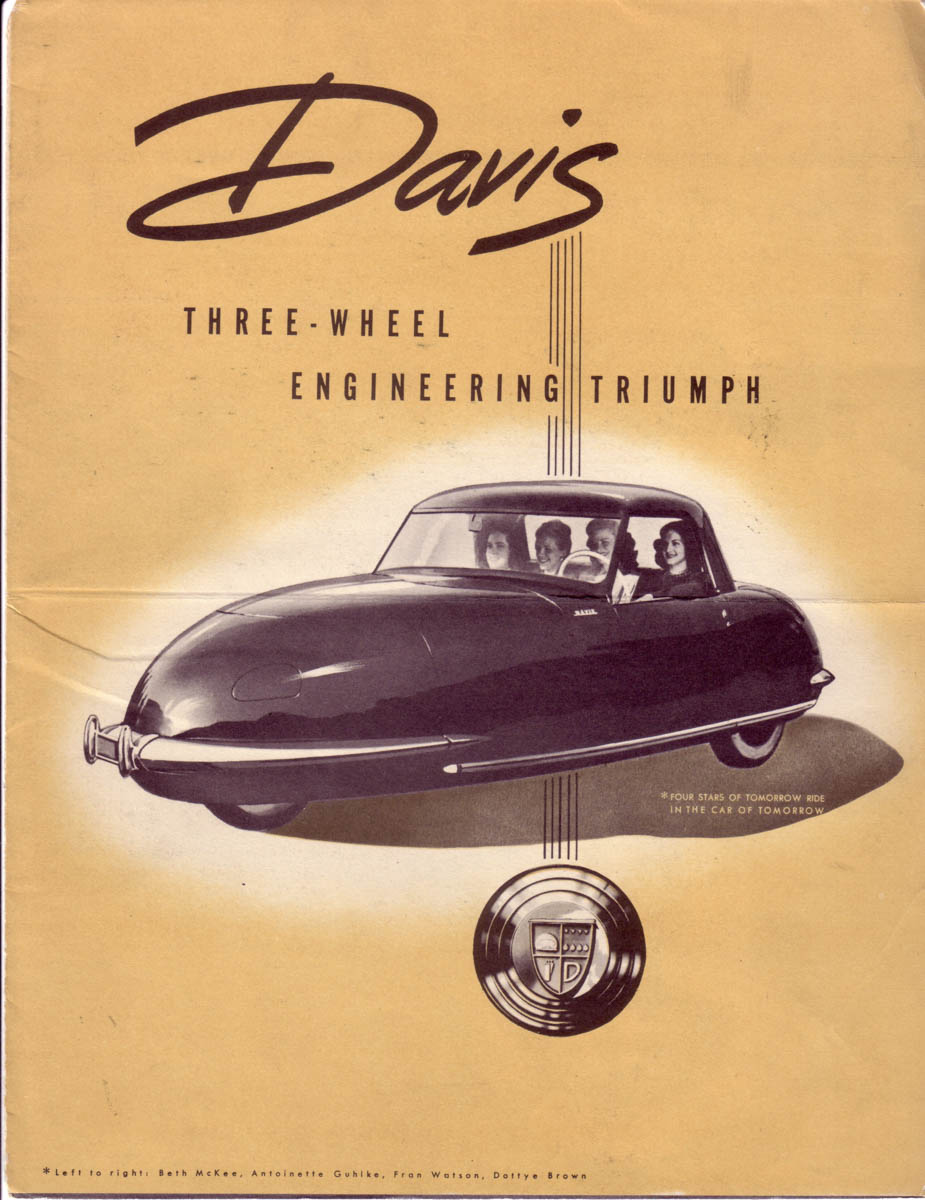

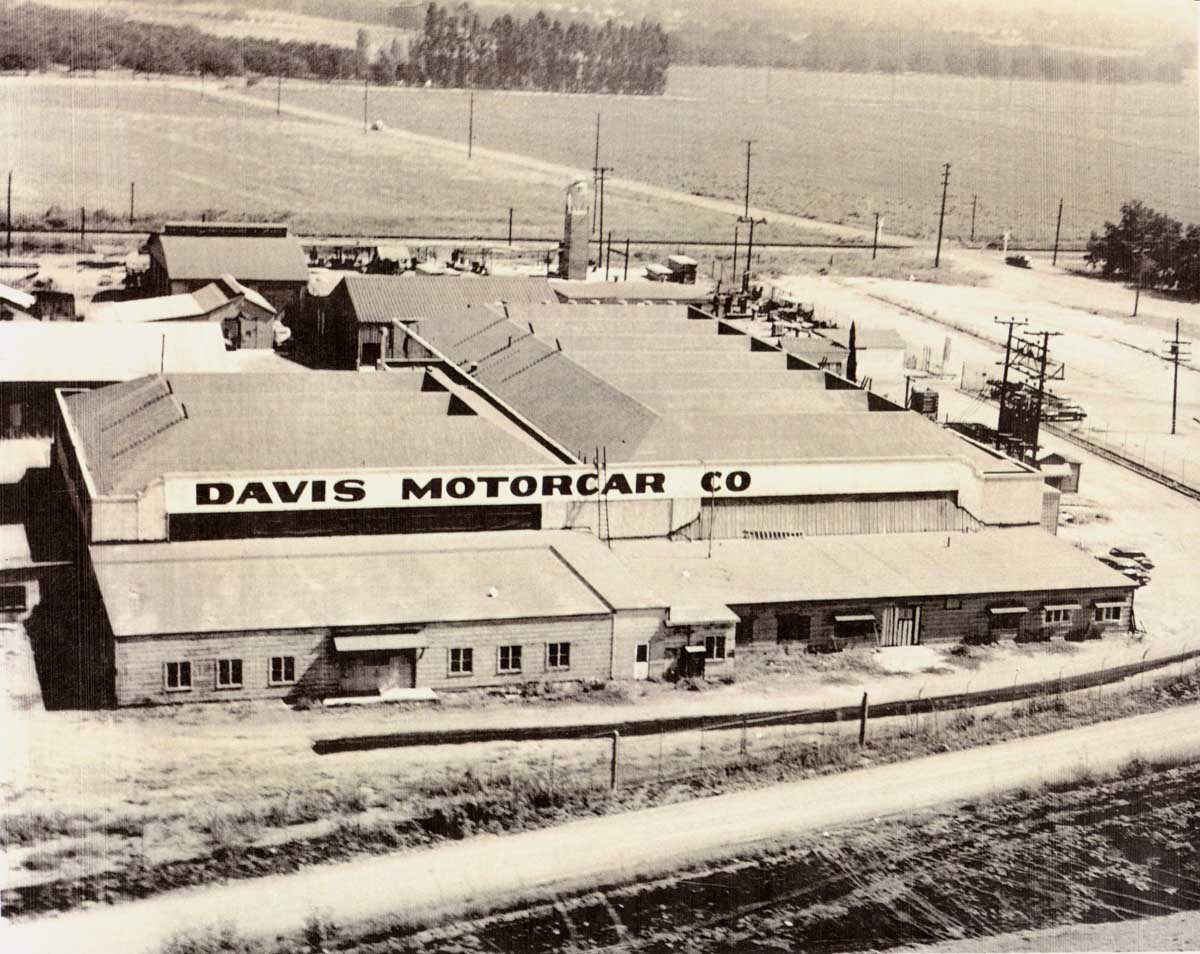

The three-wheeled Davis Divan began its life in 1941 when Indianapolis 500 racer Joel Thorne commissioned a custom vehicle from Frank Kurtis, the future founder of Kurtis-Kraft racing. Kurtis gave Thorne the Californian, and four years later, Davis somehow managed to take the car over as his own (no one is quite sure how this happened). Renamed the Divan, the car became the focus of an intense advertising campaign. New prototypes were manufactured at the new Davis Motorcar Company in Van Nuys, California. “The two-door sedan had one 15-inch wheel up front and two 15-inch driven wheels out back and was powered by a 47-hp, 132.7-cid Hercules L-head four cylinder engine (soon changed to a 63-hp, 162-cid Continental four) mated to a Borg-Warner three-speed manual. A removable hard top, covered headlights and a body shaped like a bar of soap completed the $995 package.”

The car must have looked like the future to many a prospective auto buyer—that is, had Davis ever delivered on his promises to mass produce the vehicle. Instead, only seventeen of them were ever made before the company folded.

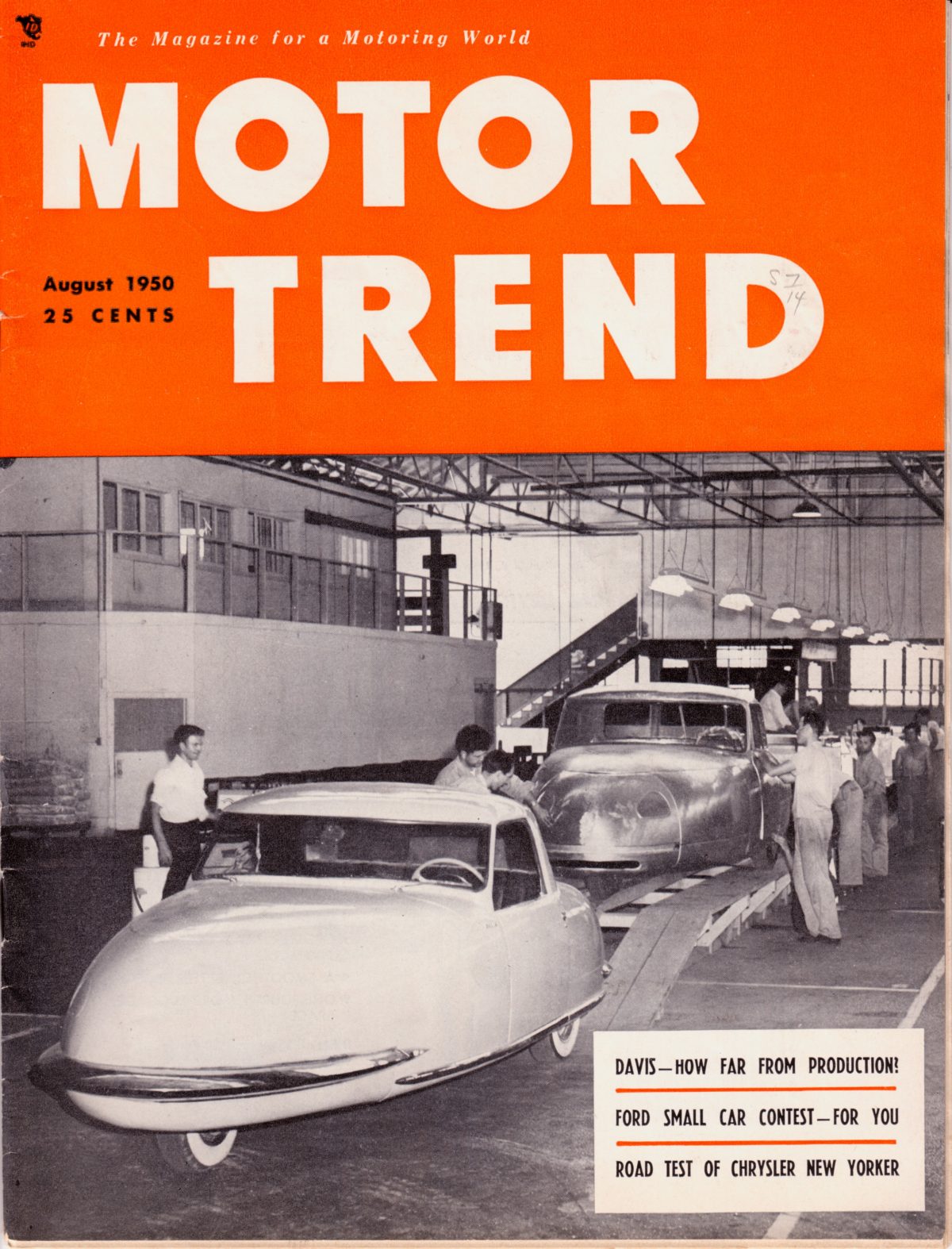

Davis Divans were soon in the news, on the covers of magazines and in newspaper ads. Franchise agreements were signed, and the quirky car looked poised for success. Yet despite the hype and the hyperbole, Davis had oversold and underfinanced his futuristic aluminum-bodied car. Impatient franchisees came looking for cars that were not there. Davis’s own employees—who initially agreed to work without salary on the promise of double pay once serial production began—began to revolt. By May 1948, the Davis Divan had gone from car of tomorrow to yesterday’s news. The Van Nuys factory was shuttered, assets were liquidated and Davis eventually served two years in prison for 20 counts of fraud.

Despite Davis’s own unreliability, the car was a solidly engineered machine that actually seated four people in its long front bench seat. Perhaps the fledgling automaker should not bear all the blame for its failure. “As always in these stories,” notes Forest Casey at Petrolicious, “it’s tough to figure out who to feel the most sorry for: the shortchanged dealers or the overworked employees. Surely it isn’t the beleaguered entrepreneur, who usually claims they were undermined by agents of the Big Three.”

Is Davis’s story “the story of Tucker and De Lorean”—a visionary outsider who couldn’t compete with the establishment? Or was he another version of that old American character so vividly captured by Herman Melville: the confidence man, selling wolf tickets to the eager while never intending to make good on his extravagant claims? No matter how we answer that question, there’s no doubt that the Divan deserves its place in automotive history as the three-wheeled engine that could… if only the financing had come through.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.