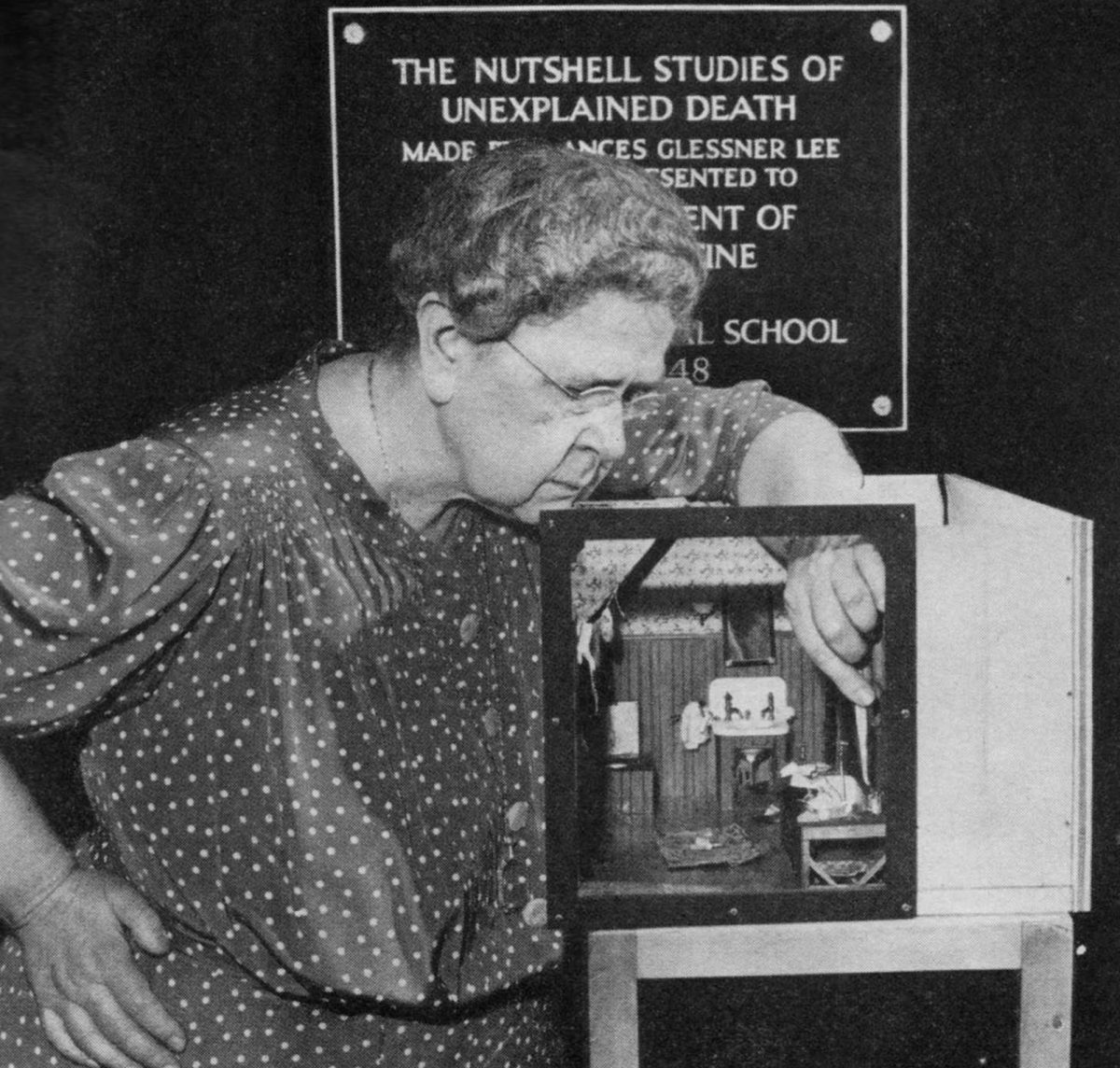

Frances Glessner Lee with her Nutshell diorama, Dark Bathroom. Image courtesy Glessner House Museum, Chicago, IL

There’s a touch of Gothic horror to Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962) hand-made dioramas of murder scenes. And like all good stuff in that seductive genre, that’s a touch of clear-eyed, innocent kitsch too. Setting and detail create atmosphere, intrigue and unease. Whodunnit? Dunno. But did you see the detail on those drapes, and you can actually read the letters scattered about the scene and soaked in the victim’s blood, which is splattered about Poe’s doll’s houses just as it would be in real life.

The detective artist’s work is being showcased in “Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. She made her scenes to train homicide investigators to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”

The scenes are contrived, of course, based on real crimes and her imagination, the corpse an Agatha Christie mannequin to trigger the sleuths’ hunt for clues. Constructed to teach students in Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine how to effectively canvass a crime scene, Lee made each component a potential clue designed to challenge trainees’ powers of observation and deduction.

Crime scene reports written by Lee under the police blotter-style line “Reported to Nutshell Laboratories” were given to forensic trainees alongside each diorama, encouraging visitors to act as the investigator, conjecturing: Was this death the result of a homicide, suicide, accident, or natural causes?

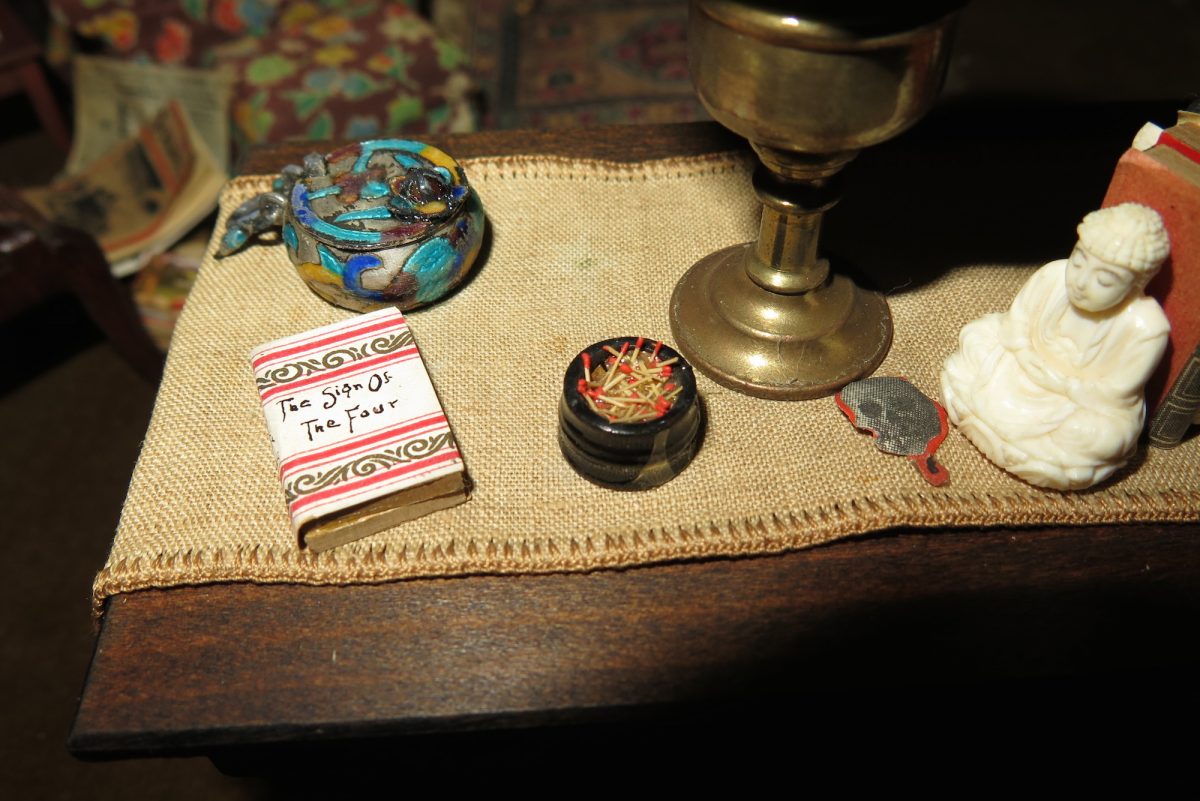

Detail of one of Frances Glessner Lee’s meticulous 1940s dioramas, Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Photograph: Corinne May Botz/Wellcome Images

HOW SHE DID IT

To assist with the project, she hired the carpenter at her estate, Ralph Moser, full time. A typical study took the duo three months and cost $3,000 to $6,000 (equivalent to $40,000 to $80,000 today), with constant reworking in consultation with Harvard chair Alan Moritz. Lee allotted duties between herself and Moser to suit their talents. Moser built the structures of the rooms and most wooden elements, like tiny working doors, windows, and chairs. He constructed every piece to Lee’s strict specifications, so much so that Lee once rejected a rocking chair made by Moser because it did not rock the same number of times as the original. To achieve a realistic patina on the siding of Barn, Lee had Moser shave slender strips of wood from an aged shed on her estate and glue two pieces together for each board. For Burnt Cabin, Moser went so far as to build the entire model, only to scorch his masterpiece with a blowtorch to convey the effects of fire.

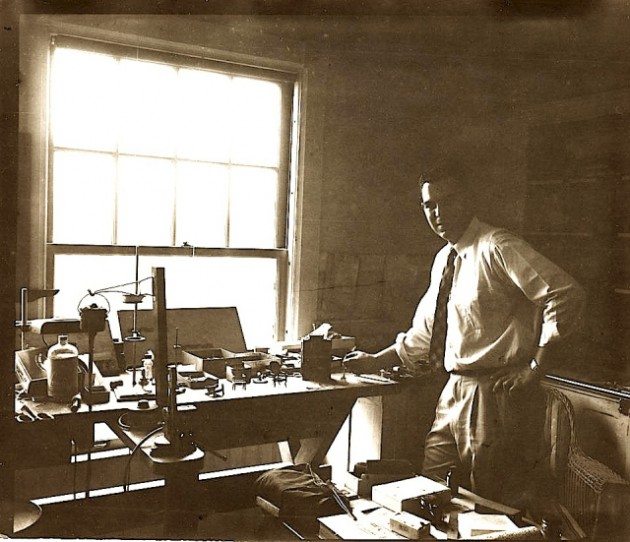

Frances G. Lee and Alan R. Moritz, head of the Department of Legal Medicine, courtesy Countway Library of Medicine

Other aspects were Lee’s domain. She often fashioned murder weapons from bracelet charms, and she took great pains to render bodies and blood evidence with scientific accuracy. The most trivial detail could provide context and circumstantial evidence—a hint for a motive or a refutation of a witness’s statement. She hand-knit tiny stockings with straight pins, addressed miniscule letters with a single-hair brush, and miniaturized the newspapers of the day. Lee would even wear clothes hopelessly out-of-date to attain the right level of wear befitting a scene.

Three-Room Dwelling (ca. 1944–46) Reported Monday, November 1, 1937

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Robert Judson, shoe factory foreman, his wife, Kate Judson, and their baby, Linda Mae Judson, found dead by neighbor Paul Abbott.

Mr. Abbott gave the following statement: Bob Judson and he drove to work together, alternating cars. This was Abbott’s week to drive. On Monday morning, November 1, he was late—about 7:35 a.m.—so, when blowing his horn didn’t bring Judson out, Abbott went to the factory without him, believing Judson would come in his own car. Sarah, Paul Abbott’s wife, gave the following statement: After Paul had left, she watched for Bob to come out. Finally, about 8:15 a.m., seeing no signs of activity at the Judson house, she went over to their porch and tried the front door, but it was locked. She knocked and called but got no answer. She then went around to the kitchen porch, but that door was also locked. She looked through the glass, and then, aroused by the sight of the gun and blood, ran home and notified the police. The model shows the premises just before Mrs. Abbott went to the house. Dawn broke at 5:00 a.m.; sunrise at 6:17 a.m.; weather clear. No lights were on in the house. Both outside doors were locked on the inside. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Three-Room Dwelling (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

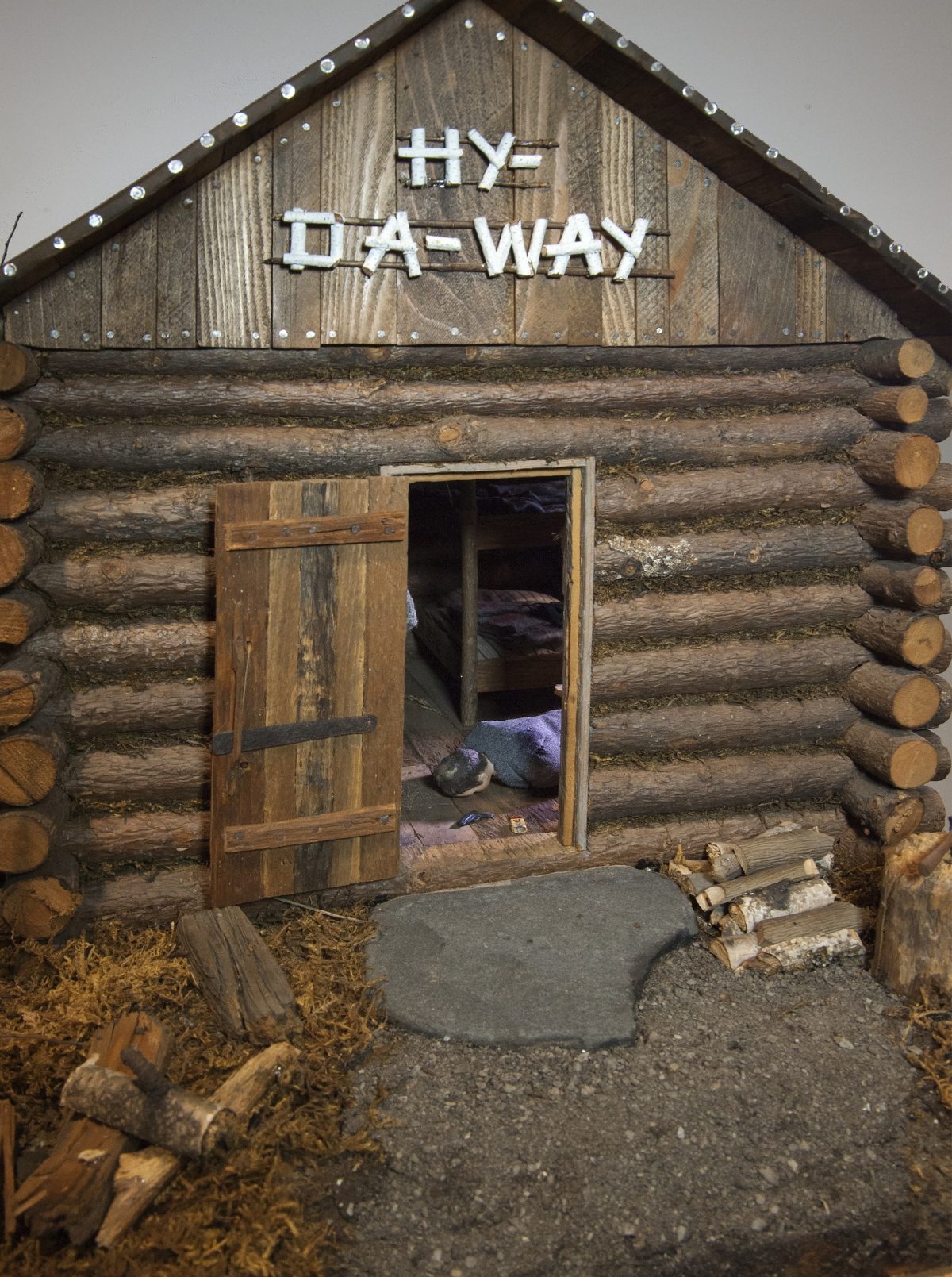

Log Cabin (ca. 1944–46) Reported Thursday, October 22, 1942

Frances Glessner Lee, Log Cabin (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Arthur Roberts, local insurance salesman, found dead by police who responded to a call from a friend of the victim, Mrs. Marian Chase. Mrs. Chase gave the following statement: She met Arthur at the log cabin on Wednesday, October 21, about 5:15pm. They were in the habit of meeting there. Roberts was married and living with his wife. Mrs. Chase was also married but not living with her husband. Roberts told her at this meeting that the affair between them was ended. There was no quarrel. They were standing at the foot of the bunk. He turned toward the door, took a pack of cigarettes from his outside pocket, selected a cigarette, but dropped it. As he stooped over to pick it up—a shot was heard, he fell flat, anda gun dropped beside him. Mrs. Chase picked up the gun but then replaced it. It did not belong to her. She then ran out of the door, jumped into her car and drove to summon the police. The gun was identified as belonging to Arthur Roberts. Mrs. Chase identified the handbag on the bunk as hers. A single bullet passed entirely through Mr. Roberts’s chest from front to back, and the powder around the entrance hole indicated it had been fired at a fairly close range. The model shows the premises just after Mrs. Chase left, and before her return with the police officer. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Log Cabin (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Log Cabin (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Striped Bedroom (ca. 1943–48) Reported Monday, April 29, 1940

Frances Glessner Lee, Striped Bedroom (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Richard Harvey, foreman in an ice-cream factory, found dead by his mother, Mary Harvey Mrs. Harvey gave the following statement: On Saturday night, April 27, Richard came home for supper as usual and after supper went back to work. He always worked late Saturday nights to get ready for the Sunday trade. She didn’t know when he came in as she went to bed early. Sunday morning she let him sleep while she went to church and then, as usual, proceeded to her sister’s for the day. When she returned home Sunday evening, Richard wasn’t around so she opened his door and found the premises as represented by the model. Richard was married about a year ago and brought his wife home to live. She was a nice girl and they were very happy. His wife was away now visiting her parents for a few days in another state. Richard was a good boy but sometimes he had a little too much to drink, especially on Saturday nights. The dishpan belonged in the kitchen. She didn’t know how it came to be in Richard’s bedroom. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Striped Bedroom (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Striped Bedroom (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Living Room (ca. 1943–48) Reported Friday, May 22, 1941

Frances Glessner Lee, Living Room (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Mrs. Ruby Davis, a housewife, found dead on the stairs by her husband, Reginald Davis Mr. Davis gave the following statement: He and his wife spent the previous evening, Thursday, May 21, quietly at home. His wife had gone upstairs to bed shortly before he had. This morning he awoke a little before 5:00 a.m. to find that his wife was not beside him in bed. After waiting a while, he got up to see where she was and found her dead body on the stairs. He at once called the family physician who, upon his arrival, immediately notified the police. The model shows the premises just before the arrival of the family physician. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Living Room (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Living Room (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Living Room (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Living Room (detail), about 1943-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Kitchen (ca. 1944–46) Reported April 11, 1944

Frances Glessner Lee, Kitchen (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Barbara Barnes, a housewife, found dead by police who responded to a call from the husband of the victim, Fred Barnes, who gave the following statement: About 4:00 p.m. on the afternoon of Tuesday, April 11, he went downtown on an errand for his wife. He returned about an hour and a half later and found the outside door to the kitchen locked. It was standing open when he left. Mr. Barnes attempted knocking and calling but got no answer. He tried the front door but it was also locked. He then went to the kitchen window, which was closed and locked. He looked in and saw what appeared to be his wife lying on the floor. He then summoned the police. The model shows the premises just before the police forced open the kitchen door. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Kitchen (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Kitchen (detail), about 1944-46. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Parsonage Parlor (ca. 1946–48) Reported Friday, August 23, 1946

Frances Glessner Lee, Parsonage Parlor, about 1946-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Dorothy Dennison, high school student, found dead after reported missing by her mother, Mrs. James Dennison. Mrs. Dennison and gave the following statement: On Monday morning, August 19, about 11:00 a.m., Dorothy walked downtown to buy some hamburger steak for dinner. She didn’t have much money in her purse. When she failed to return in time for dinner, her mother telephoned a neighbor who stated she saw the girl walking toward the market, but had not seen her since. Mrs. Dennison also telephoned the market and the proprietor said he sold Dorothy a pound of hamburger some time before noon, but didn’t notice which way she turned upon leaving the shop. By late afternoon, Mrs. Dennison, thoroughly alarmed, notified the police. Lieutenant Peale’s investigation report stated that on Monday afternoon, August 19, at 5:25 p.m., he received the telephone call from Mrs. Dennison at police headquarters, and at once took charge of the matter personally. The customary inquiries began and by Wednesday, August 21, a systematic search of all closed or unoccupied buildings in the vicinity was undertaken. It was not until Friday, August 23, 4:15 p.m., that he and Officer Patrick Sullivan entered the parsonage and found the premises as represented in the model. Temperature during that week ranged between 86°F to 92°F with high humidity. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Parsonage Parlor, collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MA. Photograph by Corinne May Botz, Parsonage Parlor (doll) from the series The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, 2004, courtesy of Benrubi Gallery and Monacelli Press

Frances Glessner Lee, Parsonage Parlor (detail), about 1946-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

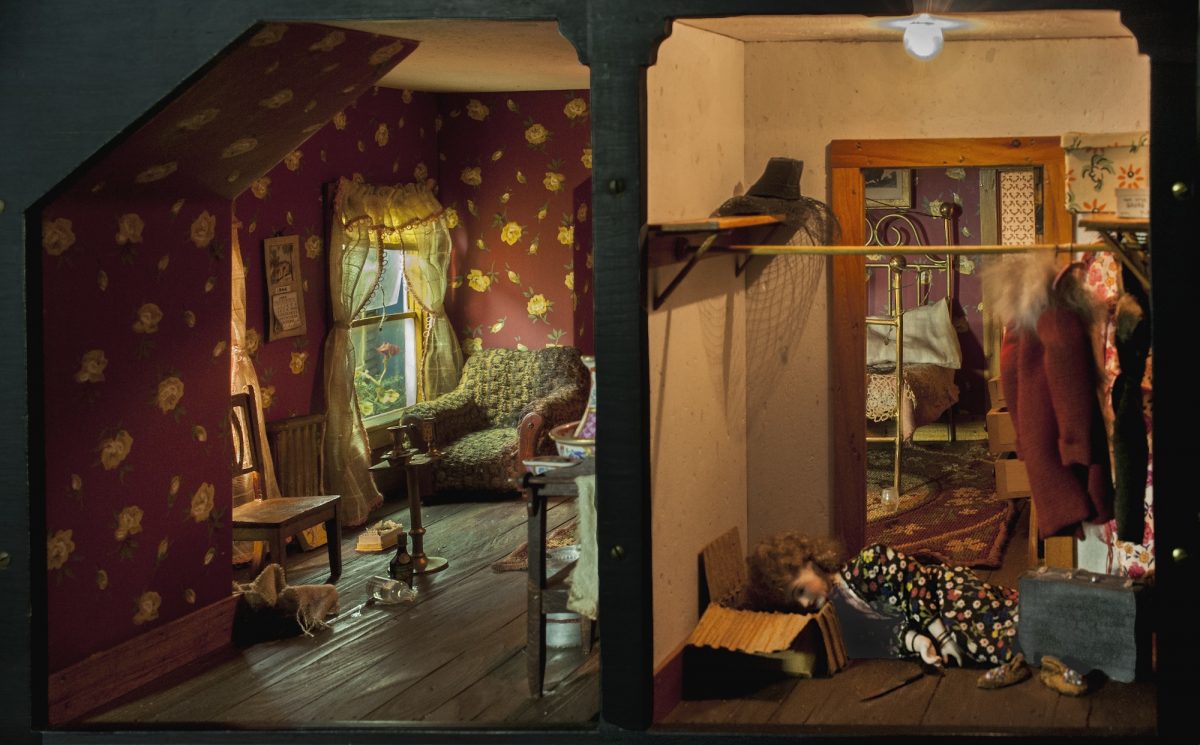

Red Bedroom (ca. 1944–48) Reported Thursday, June 29, 1944

Frances Glessner Lee, Red Bedroom, about 1944-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Marie Jones, prostitute, found dead by her landlady, Mrs. Shirley Flanagan. Mrs. Shirley Flanagan gave the following statement: On the morning of Thursday, June 29, she passed the open door of Marie’s room and called out “hello.” When she did not receive a response, she looked in and found the conditions as shown in the model. Jim Green, a boyfriend and client of Marie’s, came in with Marie the afternoon before. Mrs. Flanagan didn’t know when he left. As soon as she found Marie’s body, she telephoned the police who later found Mr. Green and brought him in for questioning. Mr. Green gave the following statement: He met Marie on the sidewalk the afternoon of June 28, and walked with her to a nearby package store where he bought two bottles of whiskey. They then went to her room where they sat smoking and drinking for some time. Marie, sitting in the big chair, got very drunk. Suddenly, without any warning, she grabbed his open jackknife, which he had used to cut the string around the package containing the bottles. She ran into the closet and shut the door. When he opened the door, he found her lying as represented by the model. He left the house immediately after that. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Red Bedroom, about 1944-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Red Bedroom, about 1944-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Barn or The Case of the Hanging Farmer (1943–44) Reported Saturday, July 15, 1939

Frances Glessner Lee, Barn, also known as “The Case of the Hanging Farmer,” about 1943-44. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Eben Wallace, local farmer, found dead by his wife, Imelda. Mrs. Imelda Wallace gave the following statement: Mr. Wallace was hard to get along with. When things didn’t go the way he wanted, he would go out to the barn, threatening suicide. Mr. Wallace would stand on a bucket and put a noose around his neck, but she would always manage to persuade him not to do it. On the afternoon of July 14, about 4:00 p.m., they had a dispute. Mr. Wallace made his usual threats, but she didn’t follow him to the barn right away. When she did go to the barn, she found the premises as represented in the model. The bucket usually stood in the corner just inside the barn door, but yesterday she used it and left it out by the pump. The rope was always kept fastened to the beam just the way it was found—it was part of the regular barn hoist. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Barn, also known as “The Case of the Hanging Farmer” (detail), about 1943-44. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD. Photograph by Susan Marks, Courtesy of Murder in a Nutshell documentary

Frances Glessner Lee, Barn, also known as “The Case of the Hanging Farmer” (detail), about 1943-44. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD. Photograph by Susan Marks, Courtesy of Murder in a Nutshell documentary

Attic (ca. 1946–48) Reported Tuesday, December 24, 1946

Jessie Comptom found dead in her house by Harry Frasier, a milk delivery man, who gave the following statement: On the morning of Tuesday, December 24, about 6:00 a.m., he stopped at Miss Comptom’s kitchen door to deliver the milk. The weather was very cold and he was surprised to find the door open. He put his head inside and called, but received no answer so he then went in to see if anything was wrong. There seemed to be nobody about. After looking the house over, he went part way up the attic stairs and saw Miss Comptom’s body hanging there, so he went downstairs and telephoned the police. Policeman John T. Adams received the telephone call at 6:43 a.m. Tuesday morning, December 24, and went at once to Miss Comptom’s house. The snow on the path to the kitchen door was somewhat trampled and no distinct footprints could be recognized. There were unwashed dishes for one person on the kitchen table. The house downstairs was neat. The bed was made and undisturbed. However, he found the attic as represented in the model. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

rances Glessner Lee, Attic (detail), about 1946-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD. Photograph by Susan Marks, Courtesy of Murder in a Nutshell documentary

Frances Glessner Lee, Attic (detail), about 1946-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD. Photograph by Susan Marks, Courtesy of Murder in a Nutshell documentary

Burned Cabin (ca. 1944–48) Reported Sunday, August 15, 1943

Frances Glessner Lee, Burned Cabin (detail), about 1944-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Daniel Perkins was missing and presumed dead. Phillip, Daniel Perkins’s nephew, gave the following statement: On Saturday evening, August 14, he came to spend the night with his uncle, as he frequently did. In the middle of the night, he was wakened by the smell of smoke and ran outside to find the house on fire and the fire engines arriving. He said he had been very confused and could not remember any other details. Joseph McCarthy, driver of fire engine #6, gave the following statement: The call to the fire was received at 1:30 a.m., Sunday, August 15. Upon arrival, the fire was quickly extinguished before the building was completely destroyed. He noticed Phillip, fully clothed, wandering around near the house. The model represents the premises after the fire was extinguished and before the investigation. Collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

Frances Glessner Lee, Burned Cabin (detail), about 1944-48. Collection of the Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, MD

BIOG

Despite academic leanings, Frances did not attend college and at nineteen married a young lawyer named Blewett Lee. Assuming the role of affluent wife and mother, she pursued appropriate feminine pastimes, planned parties, and attended philanthropic events, but grew unhappy. After sixteen years and three children, the marriage dissolved, a split her son later attributed to Frances’s “creative urge coupled with . . . the desire to make things—which [Blewett] did not share.”

Frances Glessner Lee at work on the Nutshells in the early 1940s. Image courtesy Glessner House Museum, Chicago, IL

Frances Glessner Lee was born in Chicago in 1878 to John and Frances Glessner and as heiress to the International Harvester fortune. From an early age, she had an affinity for mysteries and medical texts, spurred by the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, who first appeared in print in 1887. During and after her marriage, Frances’s morbid fascinations persisted, and she found a kindred spirit in George Burgess Magrath, whom she met in the summer of 1898. Magrath studied medicine at Harvard, specializing in death investigation, and later became Medical Examiner of Suffolk County. He fueled her imagination with true tales of murder and mystery and delighted her with his respect. Recognizing her as an equal, he confided his concerns about the young field—like the poor training of investigators who often overlooked or contaminated key evidence at crime scenes. When Frances’s brother passed away in 1929, she made a gift to Harvard in his honor, helping to establish the first-of-its-kind Department of Legal Medicine.

Later, in 1936, she inherited her fortune and was finally free to pursue her passion. No longer under the watchful eye of her parents and a society that disapproved of her interests, she began working with her local New Hampshire police department, earning the title of Police Captain – the first woman in the country to achieve that rank.

In 1943, at the age of sixty-five, she finally began work on her series of grisly dioramas, The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Proving an ingenious solution to the problem Magrath voiced years earlier, the miniatures not only taught investigators how to properly canvass a scene, but also challenged their biases. A pioneering tool for forensic teaching, they also testify to the determination of Captain Lee, as she liked to be called, who used her cunningness and craft to break the glass ceiling and advocate for others who did not have a voice. “Convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”

‘Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death’ – is at the Renwick Gallery.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.