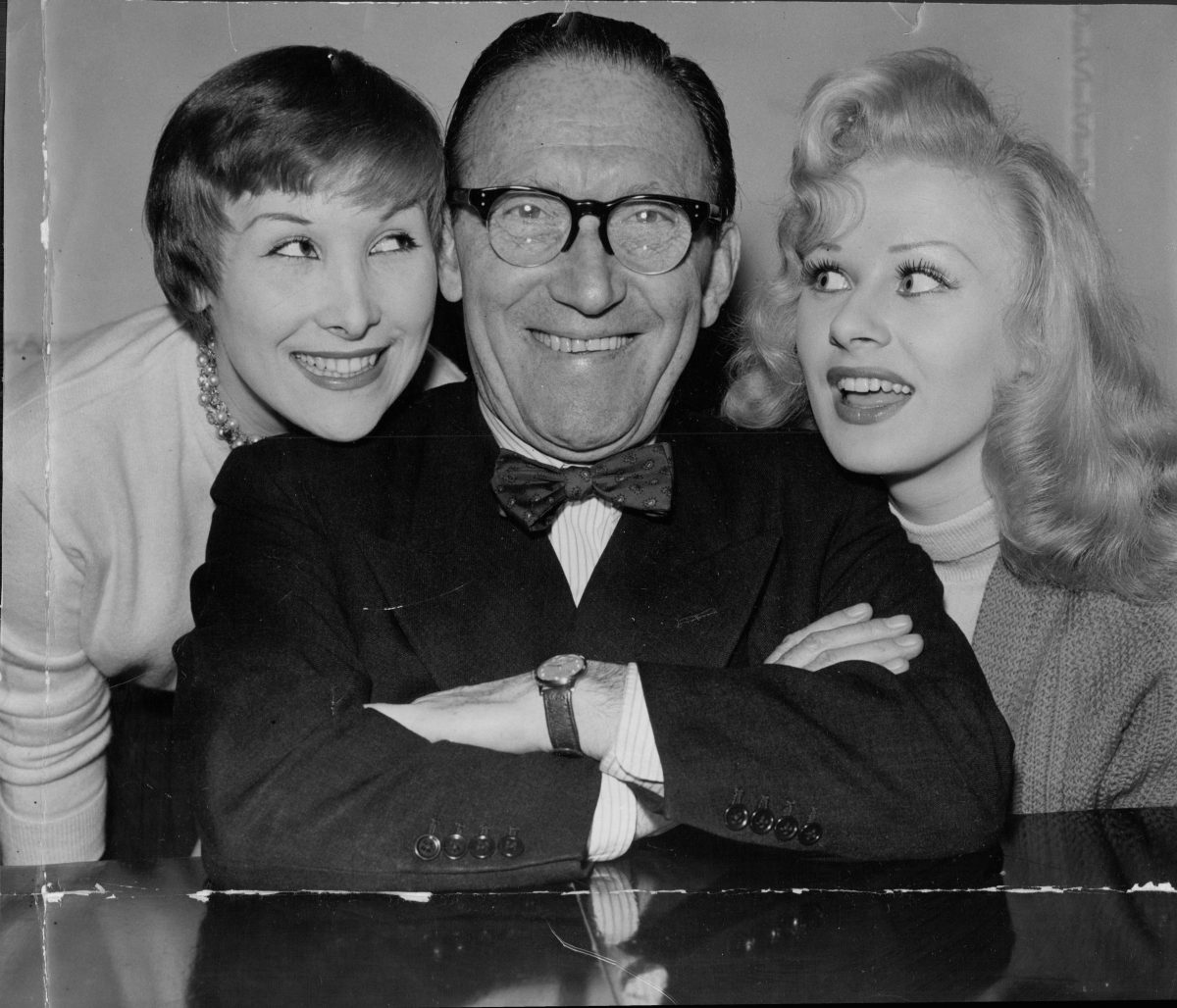

Glamour model and actress Sabrina seated on the knee of Arthur Askey. Original Publication: People Disc –

She was a brassy blonde whose cleavage was a ticket to fame and fortune. She played dumb and acted smart. She was a one-woman industry with a one-word name: not Jordan, but Sabrina ((19 May 1936 – 24 November 2016).

Before she was Sabrina, she was Norma Sykes of Stockport, Cheshire. A junior swimming champion (breaststroke, naturally) at the age of 12, she might have become a ‘golden girl’ of the pool. Alternatively, she could have ended up working at her mum’s B&B in Blackpool.

An attack of polio changed everything. Two years in hospital (where doctors operated and considered amputation) were followed by months of rehab in the pool and gym. What didn’t kill her made her stronger, and her well-developed arms, legs and pecs would serve her well when she upped sticks and headed for the Smoke at the age of 16.

At 16 she moved to London and lived alone in a rented windowless attic room in King’s Cross. She made jewellery and sold it at local shops. She survived on bread, potatoes and baked beans. She had a voluptuous figure, with a 41in bust and 18in waist. ‘‘I soon realised the effect my figure had on people,’’ she said. ‘‘They would frequently stop and stare at me in the street, especially if I was wearing a sweater.’’ Sydney Aylett, a barristers’ clerk and keen photographer, became a friend. ‘‘It seemed every man’s head turned towards her,’’ he said. ‘‘And from the looks, which ranged from admiration to downright lechery, it became apparent she had something. It wasn’t just the bosom; she radiated a sort of sensual purity, which sounds like a contradiction in terms.’’

Aylett introduced her to luminaries in show business, but first he met her mother. He told her that film stars such as Jane Russell, Jayne Mansfield and Monroe had made “big bosom big business”. Aylett wrote later: “Mrs Sykes took my point, albeit a little rustically. ‘Aye, I see what you mean,’ she broke in, ‘and our Norma’s got a couple of beauties, hasn’t she?’ ’’ Annie Sykes was to remain close to her daughter, travelling across the globe at her side. – Times

The big break came two years later in February 1955. Arthur Askey was fronting a BBC television show, Before Your Very Eyes, and he wanted a ‘dumb-cluck’ for comic purposes. Norma was in the right place at the right time. She was 18 years of age, with a new hair colour (peroxide blonde), a bigger-than-ever bust (42 inches), a smaller-than-ever waist (17 inches), and, courtesy of Askey, a new name that nobody would be allowed to forget.

If Sabrina’s physical appearance was remarkable, it was nowhere near as remarkable as the fact that she was appearing on national TV at all. Here was a woman who, as Askey himself put it, “could not act, sing, dance, or even walk properly”. Her total contribution to the programme was to speak one solitary line and wander around in a tight dress. Yet that was enough to start a revolution in the staid world of British showbiz.

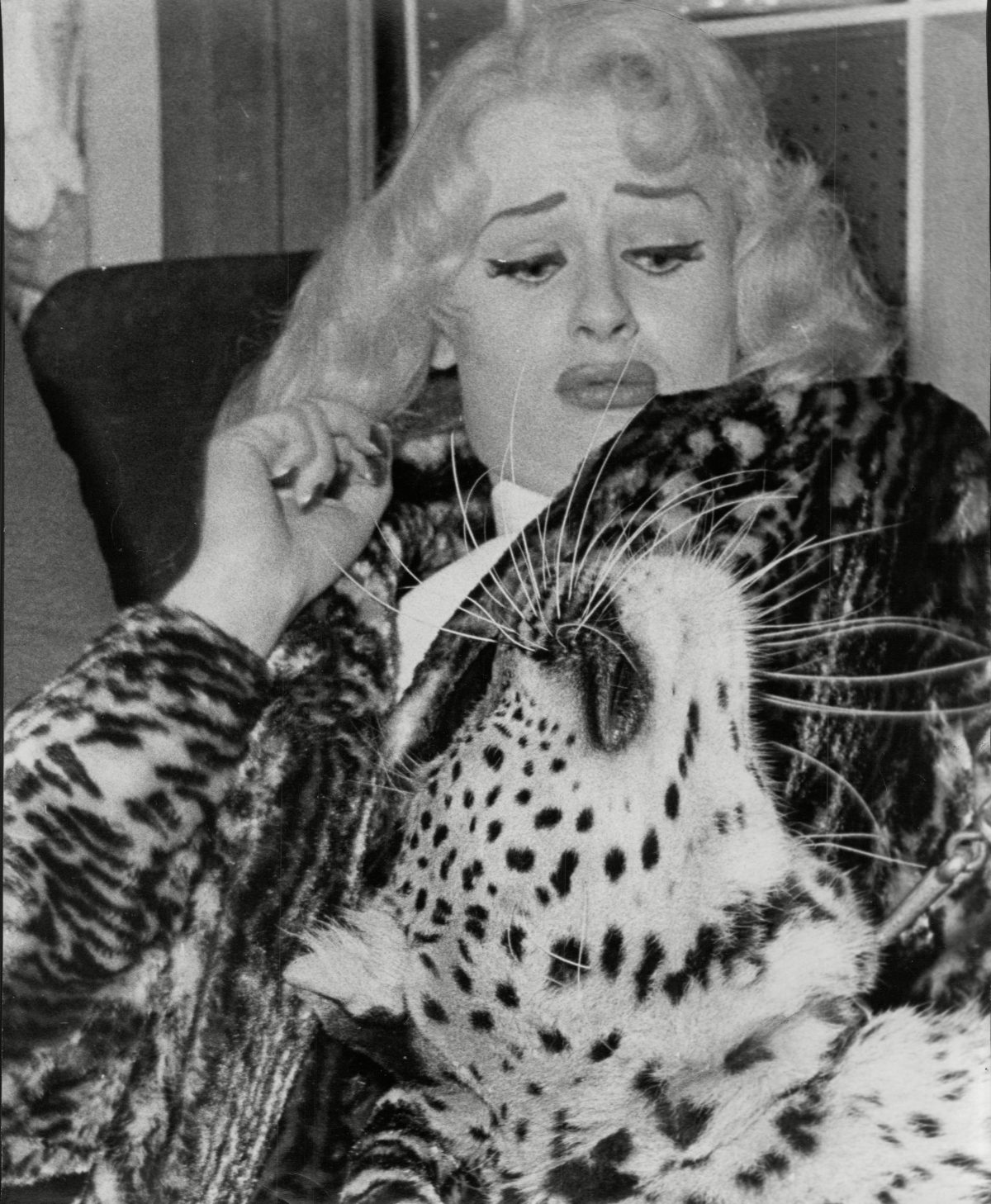

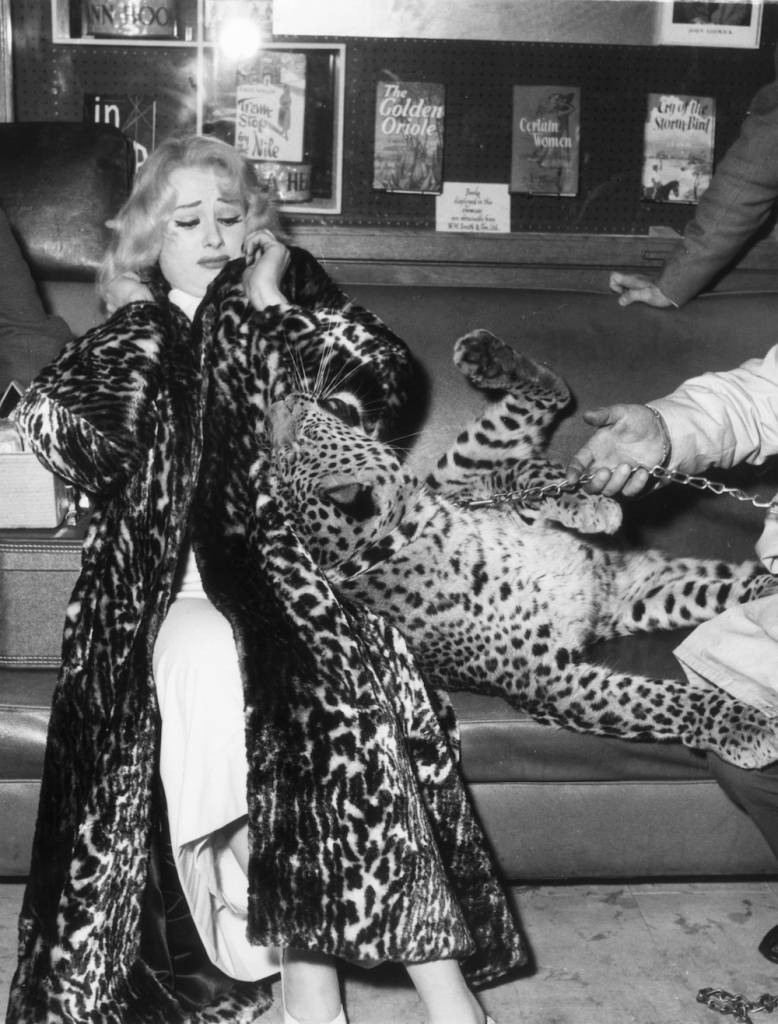

2nd March 1958: Glamour model and actress, Sabrina, wearing an animal skin fur coat, recoiling from the attentions of a leopard cub on a leash.

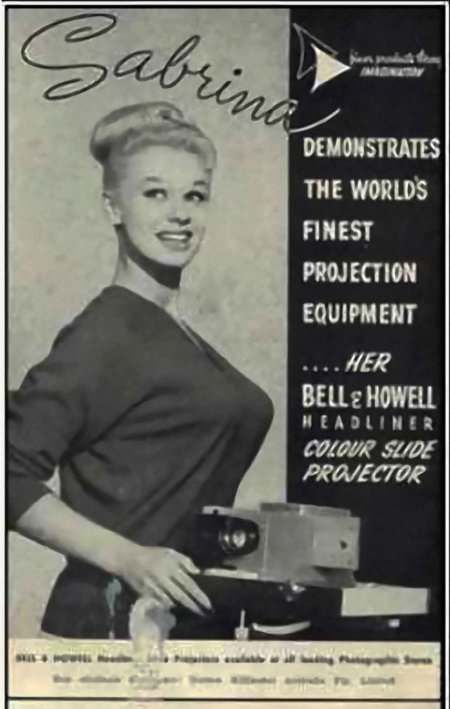

Sabrina was an overnight sensation. Her picture was in every newspaper and magazine and her name was on every tongue. She drew massive crowds to her ‘personal appearances’ at shops and clubs, and occasionally provoked near riots with her wardrobe malfunctions. Her breasts were insured with Lloyd’s of London, and she hit the headlines at Ascot by gate-crashing the royal enclosure. “How long can it go on?” asked Photoplay magazine in 1956. “How far can she go on her dumb blonde gimmick?”

The answer: further than anyone – including herself – would ever have imagined. Before long she was a household name, a national treasure, and a Goon Show catchphrase to boot (“By the measurements of Sabrina!”). Audrey Hepburn’s film Sabrina was re-titled for its British release, as Sabrina launched her own movie career. Her debut, Blue Murder at St Trinian’s, was another triumph of self-promotion. Although she had no lines, and her performance consisted of sitting up in bed wearing a nightdress, it was enough to secure equal billing with Alastair Simms. “Hers was a very British fame: cheesy, cheap and cheerful,” writes Cosmo Landesman in his meditation on celebrity, Starstruck: Fame, Failure, My Family and Me. “It was imitation Hollywood with a touch of saucy seaside postcard vulgarity.”

1955: Sabrina, Britain’s answer to Marilyn Monroe, snatches a sandwich as she chats with British comic Tony Hancock during a function at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

After this initial success, Sabrina began to turned up in the unlikeliest of places. Those who complain of the dumbing-down of academia, or the Spice Girls’ prominent role in Nelson Mandela’s birthday celebrations might be surprised to learn that Sabrina was a trailblazer in this field too. In 1959, for example, she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Leeds, and the following year she ruffled feathers in cold-war America by meeting Fidel Castro in Cuba.

As her fame spread around the globe, she was romantically linked with a series of high-profile partners, including Frank Sinatra, Sean Connery, Joe DiMaggio, and the writer Abby Mann. In the end, though, she married a plastic surgeon in Hollywood – for love, presumably, as she must have been the only woman in Tinseltown with no use for his professional services. They divorced ten years later. He had no sense of humour, she complained later: “I couldn’t believe I ended up marrying a German.”

1st May 1965: A wax head of Frankenstein and torso of film starlet, Sabrina at Gem’s (Wax Models) Ltd, in the Portobello Road area of west London. The company makes store mannequins and models of all kinds for exhibition all over the world.

When considering Sabrina’s unlikely fame, it is tempting to wonder whether this was the inspiration for the colloquial use of the word ‘talent’ as a collective noun for attractive well-built women. Sabina herself certainly appreciated the irony of her situation, and her initial reaction to success suggests that she shared the general bafflement. After her first television performance she was a model of self-effacement. “I’m just a dumb blonde,” she told reporters.

The truth, of course, was that Sabrina was nothing of the sort. She went along with the public image for as long as it suited her, but she was always looking ahead. Two years later, she was asked what ambitions she harboured. “Literally everything,” she replied.

Her subsequent career, while not quite achieving “everything”, still stands as a testimony to her shrewdness, determination, and self-reliance (she never had an agent). Her real legacy, however, is not her work on stage and screen. It is the way in which she rewrote the rulebook of fame. It can be seen today in the young Normas and Katies dreaming of becoming tomorrow’s Sabrinas and Jordans, and looking for the shortest possible route from Z to A. Blame Arthur Askey, I say.

He started it.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.