In May 1943, anthropologist and Office of War Information / Farm Security Administration photographer John Collier (May 22, 1913 – February 25, 1992) and his wife and work partner Mary E. T. Collier paid a visit to the woodsmen in western Maine close to the New Hampshire border.

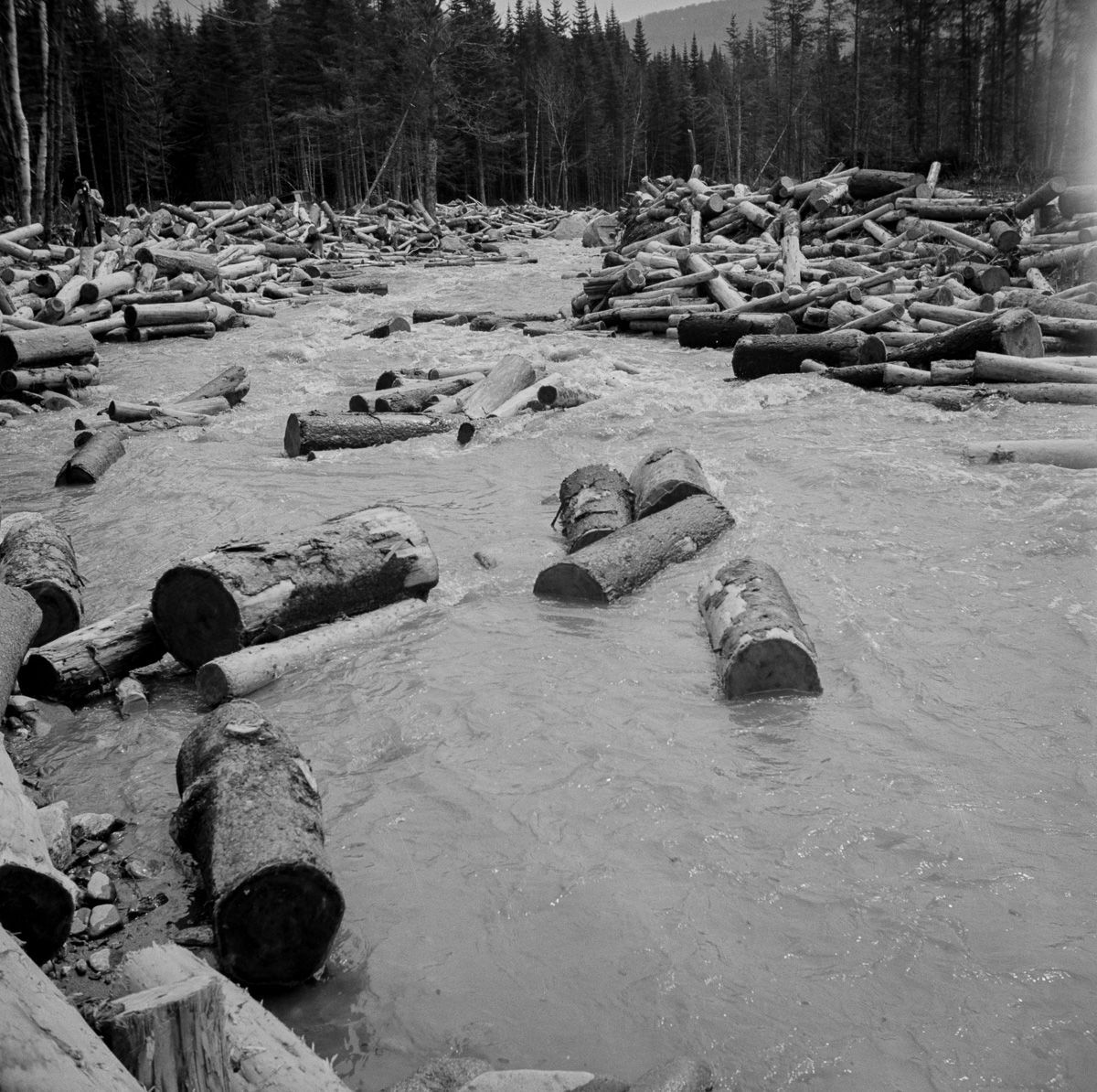

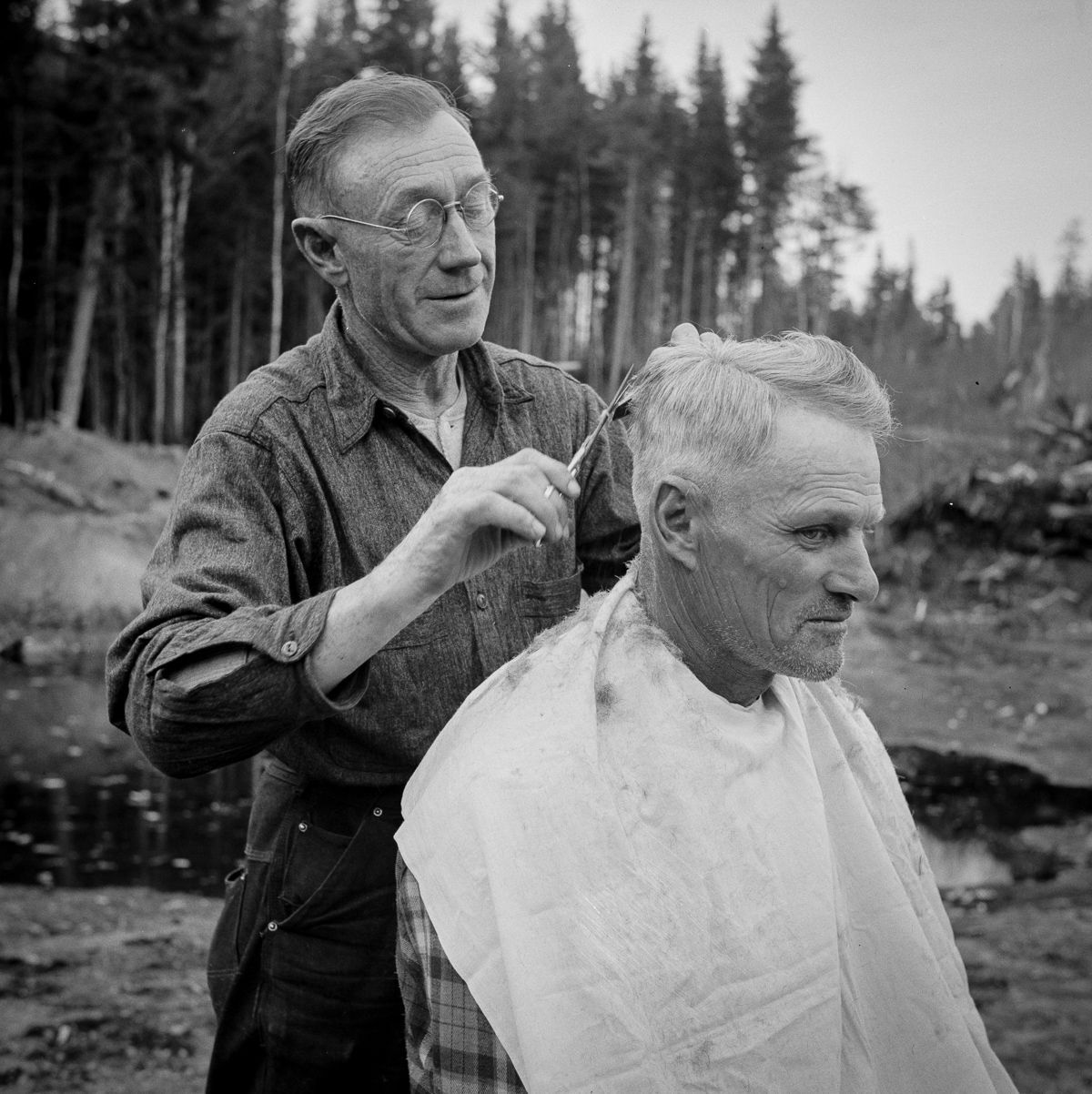

They photographed the woodsmen, who worked 13-hour days on the spring wood pulp drive down the Kennebago River and Mooselookmeguntic Lake, dressed in spiked shoes and wielding long pikes to guide logs toward pulp and paper mills. Collier camped with the men, joined them for their four daily meals and shared their bunkhouse.

Collier spoke about his work in 1965 in an interview with Richard K. Doud.

Before that, a few words about why he was often known as John Collier Junior. His father, John Collier (May 4, 1884 – May 8, 1968) was a sociologist, writer, social reformer and Native American advocate. He served as Commissioner for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the President Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, from 1933 to 1945. He was chiefly responsible for the “Indian New Deal”, especially the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, through which he intended to reverse a long-standing policy of cultural assimilation of Native Americans.

Here’s his son speaking about his own career:

I got interested in photography in the first place because of the fact that I had a career as a mural painter and an artist on the project under Dorthea Lange’s first husband, Maynard Dixon, a Western painter. And I decided to make that my career.

For medical reasons I didn’t go to school and so I devoted myself to the fine arts. Then it became apparent that I had to find a place for myself in society and make a living and after a good many years of investing very deeply in both painting and writing I looked about for some means of exchange that would allow me to operate in society.

I also was very disturbed because I was in the midst of the great depression and I was alarmed at the documentary material, particularly material that tended to be social propaganda, made very bad art. And I wasn’t at all pleased with painting as a medium for expressing my intellectual feelings about society. So I decided to shift to a medium that was more articulate and I turned to photography because it seemed capable of being able to handle the problem of documentation and understanding without getting involved with a decadent level of fine art. Also photography was a needed commodity, people needed pictures; they did not need my painting nor my writing.

And under the pressure of the great depression I felt the necessity of contributing and being needed. And though I was an assistant on a mural on the WPA I didn’t feel it was an objective enough job. So I decided I should become some kind of a student of what was going on. Painting was no medium for this kind of introspective examination so I decided to go to my own cultural field, the Spanish Southwest where I had grown up, to try to work out some better understanding of Spanish-American culture. And the first project that I was involved with I prepared for by six months reading in the Bancroft Library at the University of California. I went into the Southwest and made a personally financed document on the Spanish-American sheep camp. And it was on the basis of this document that I was hired by Roy Stryker. I had shown the document to Dorothea Lange, and Dorothea Lange was a childhood friend of mine.

– John Collier

So I knew Dorothea Lange, I was a photographer and knew about photography. After completing this document Dorothea Lange suggested that I send it to Roy Stryker along with other work. I sent it and forgot all about it. Maybe months went by and I ended up with one photographic job after another, finally reaching the bottom being a printer for Gabriel Milan’s, a very cutthroat photographic company in San Francisco. And I didn’t do well.

One time a phone call came into the laboratory from Washington, D.C. And there was much excitement in the laboratory, and I was called out of my little dungeon where I was tinting gold-toned baby portraits and picked up the phone and couldn’t hear what the man said, having lifelong hearing difficulty. It was Roy Stryker on the phone, so I handed the phone to the nearest person, who was the boss. And the boss listened and he said, “There’s a crazy guy in Washington, D.C. who wants to pay you $2,300 a year. You’d better take it because I’m going to fire you.”

So I took up the phone and I said, “Yes.” I didn’t hear anything else that he said, and immediately prepared to leave for Washington, D.C. But this was the climax of the concern that I had to do something about direct analysis and observation about what was going on around me at the time of the great depression.

– John Collier

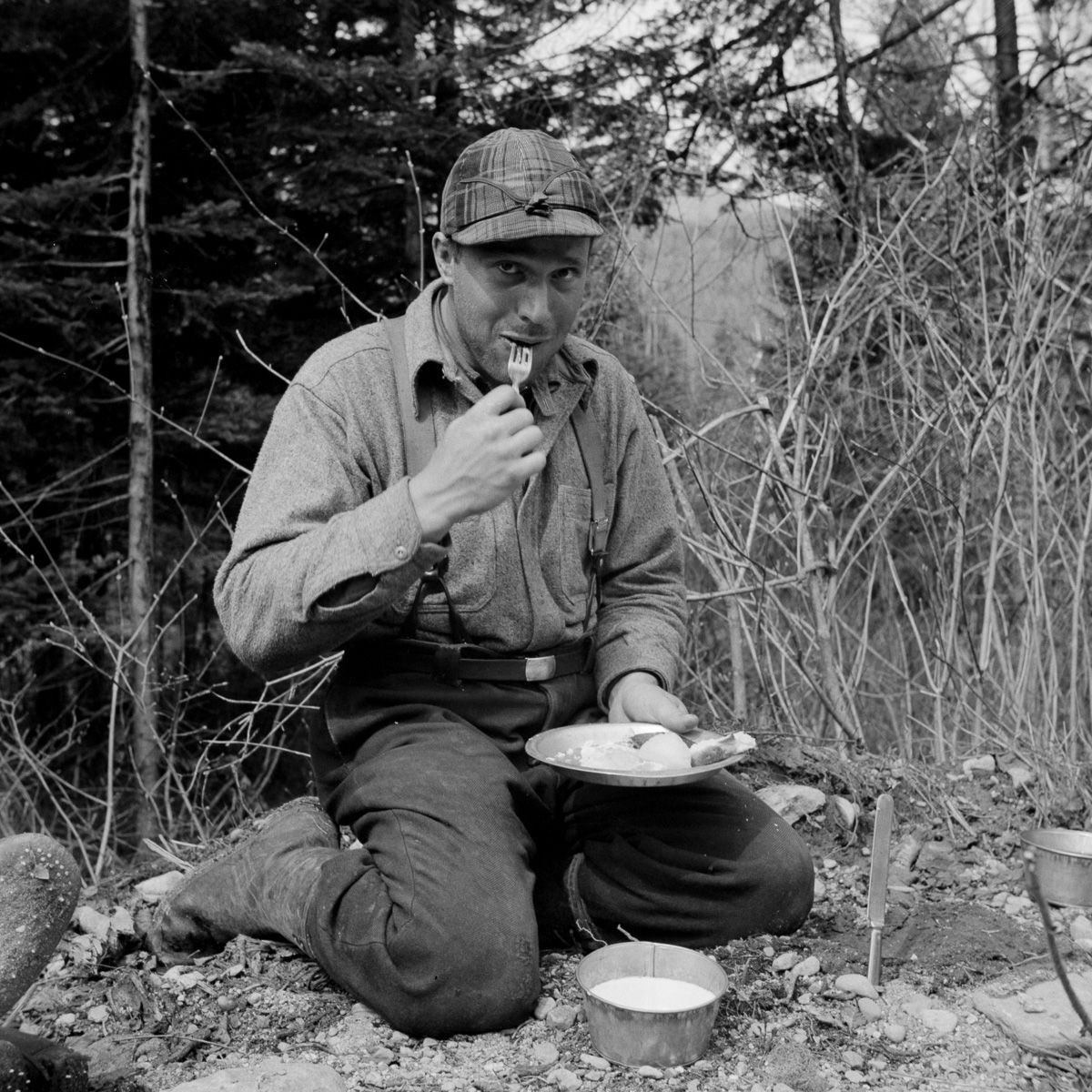

Photographer’s wife appreciates four meals a day along with woodsmen in Maine

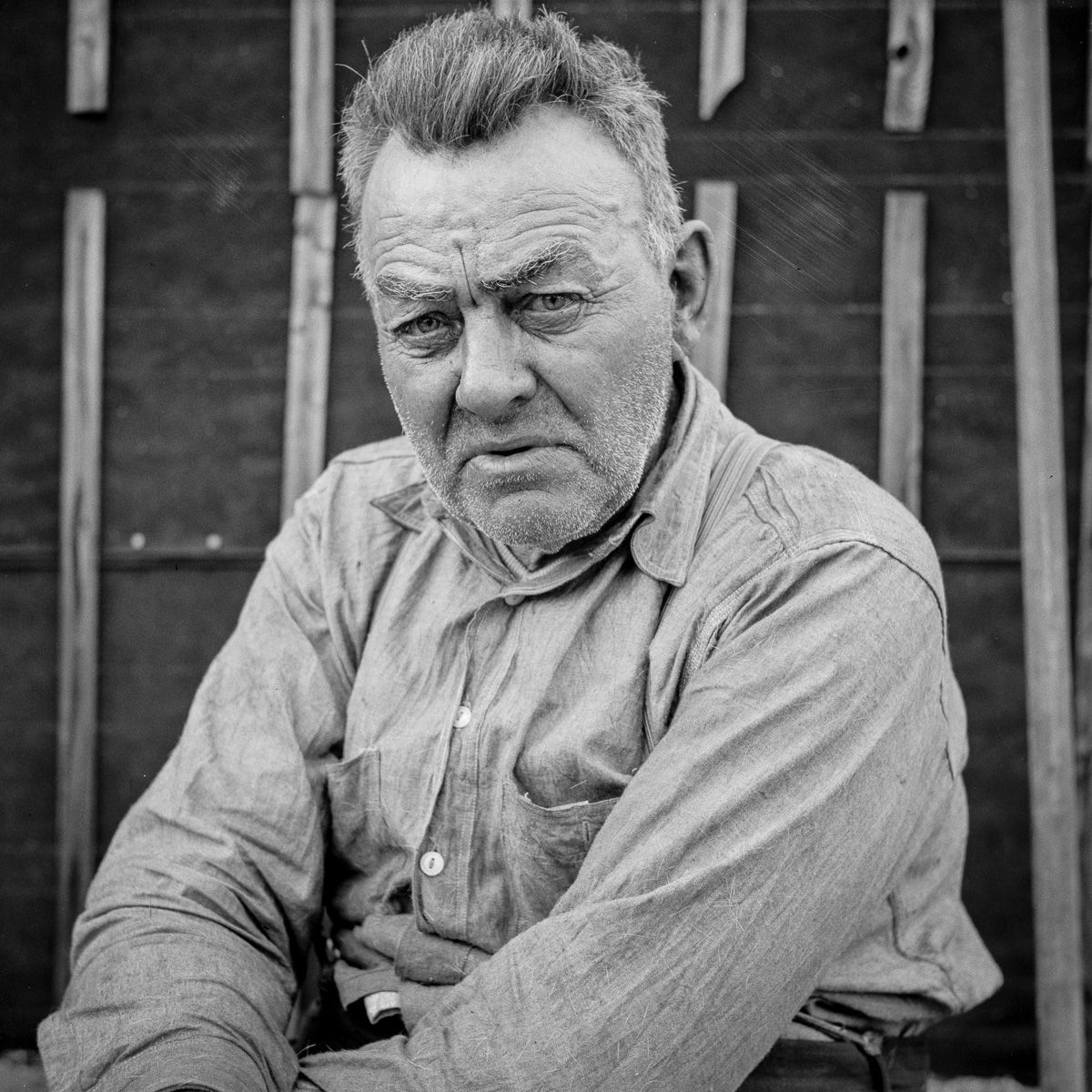

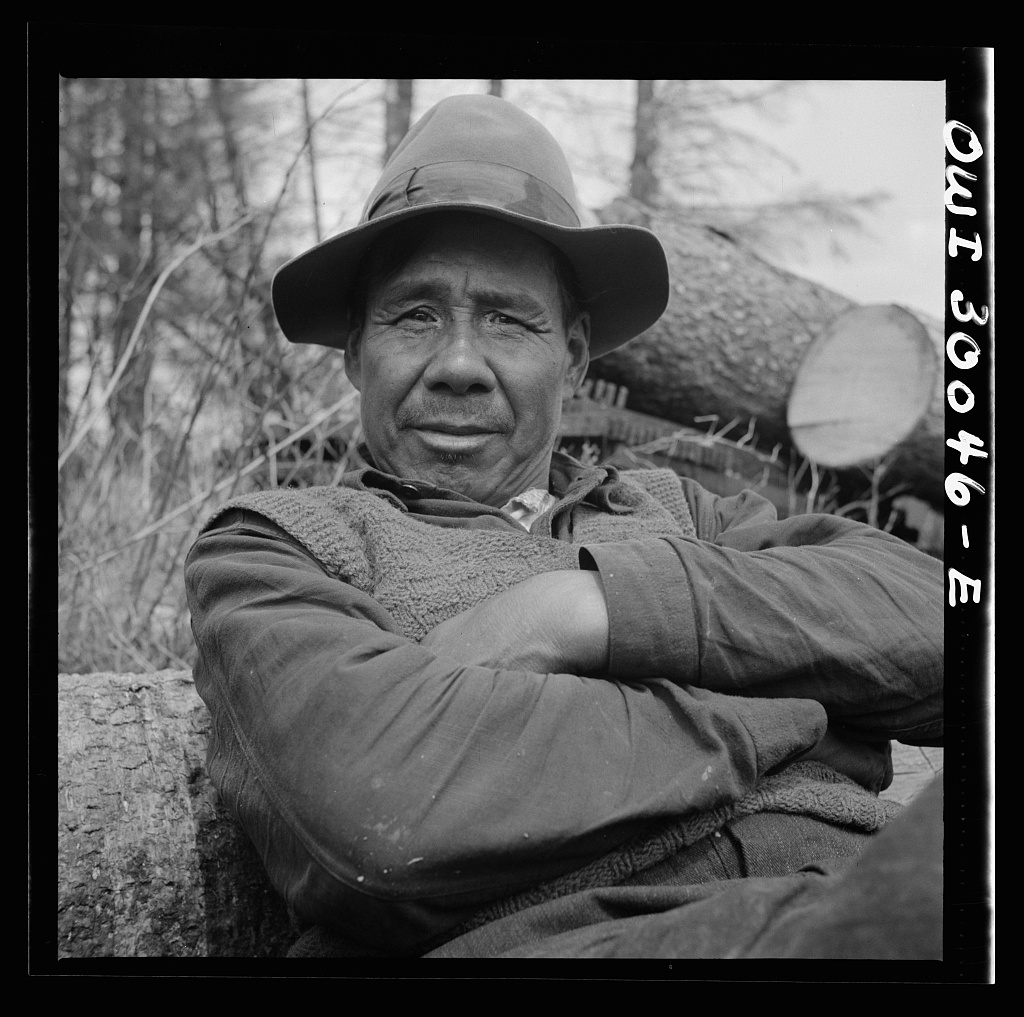

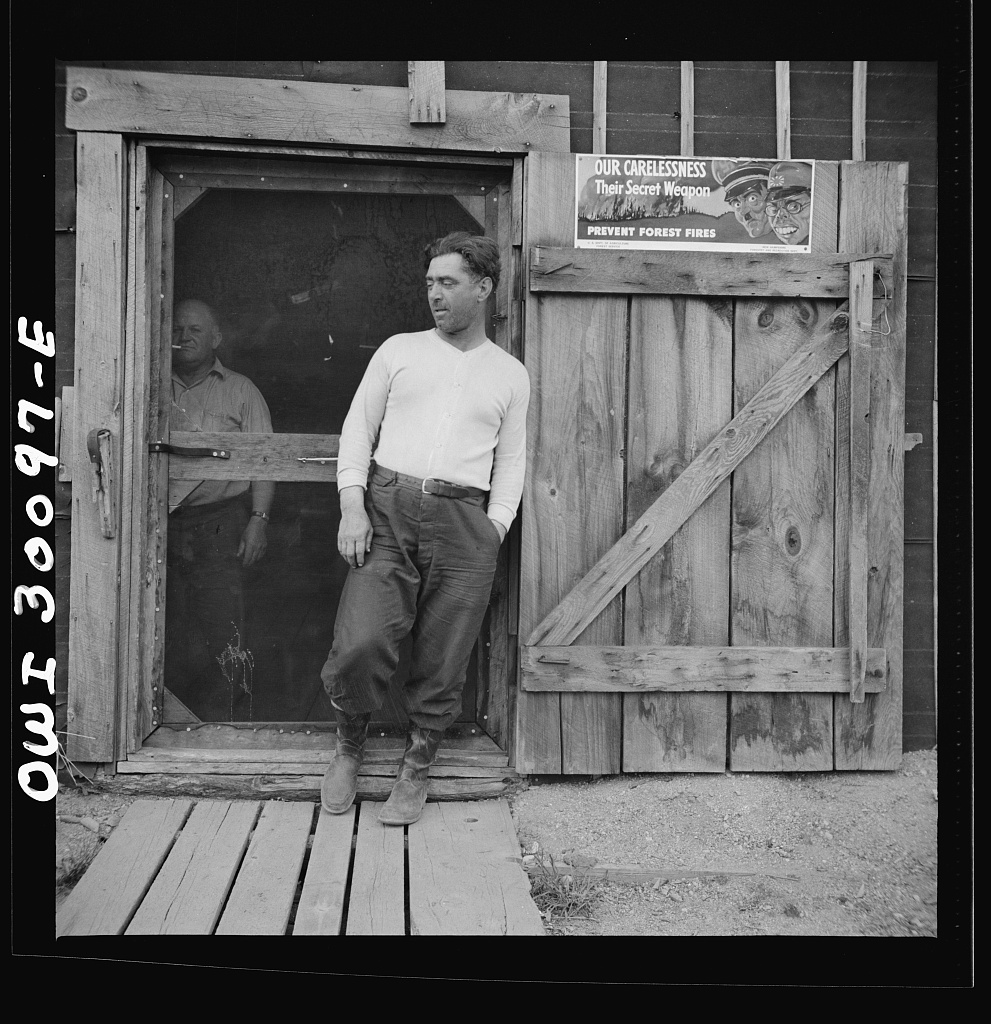

French Canadian woodsman takes a break

Maine Woodsmen took 4 meals breaks a day

Wearing spiked shoes and wielding pikes, Maine woodsmen guide the logs

Maine Woodsmen – via Library of Congress

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.