“Two hundred miles an hour!” I said. “That will mean the run from New York to San Francisco in a single day?”

“Easily. And pleasantly, too; for you must bear in mind that these cars will be different from any cars thus far known. They will not be cars at all, but great, beautiful parlors, where we shall travel almost without knowing that we are traveling; where we shall find the comforts and luxuries of a first-class hotel, brilliant dining-rooms like saloons on the best ocean liners, spacious libraries and smoking-rooms, entertainment-rooms for music or dancing, and, of course, large, well-ventilated sleeping-rooms instead of the wretched bunks behind dusty curtains.”

– Inventor Louis Brennan in conversation with journalist Cleveland Moffett, 1907

Since the modern transportation era of steam engines and railroads began, engineers have dreamed of monorails. The single-track trains have served as both practical transport alternatives and sci-fi symbols of a glorious new future. By the mid-1960s, monorails were the height of futurist chic. Full-color, space-age illustrations of the monorail at the 1964/65 New York City World’s Fair adorned matchbooks, pamphlets, poster, and guidebooks—the culmination of over 100 years of monorail research and development.

The first patent for a single-track rail line was filed in the UK on November 22, 1821 by Henry Palmer, for a horse-drawn vehicle that straddled an elevated rail. Other, steam-driven, designs followed throughout the 19th century, many proposed as cheaper, faster means of moving resources and commodities across the expanding empire. Many of these so-called monorail systems actually used two tracks—one below and one above to stabilize the train (called a “bicycle railroad”). Some of the first true monorails to use only a single track and train solved the problem of balance with gyroscopes.

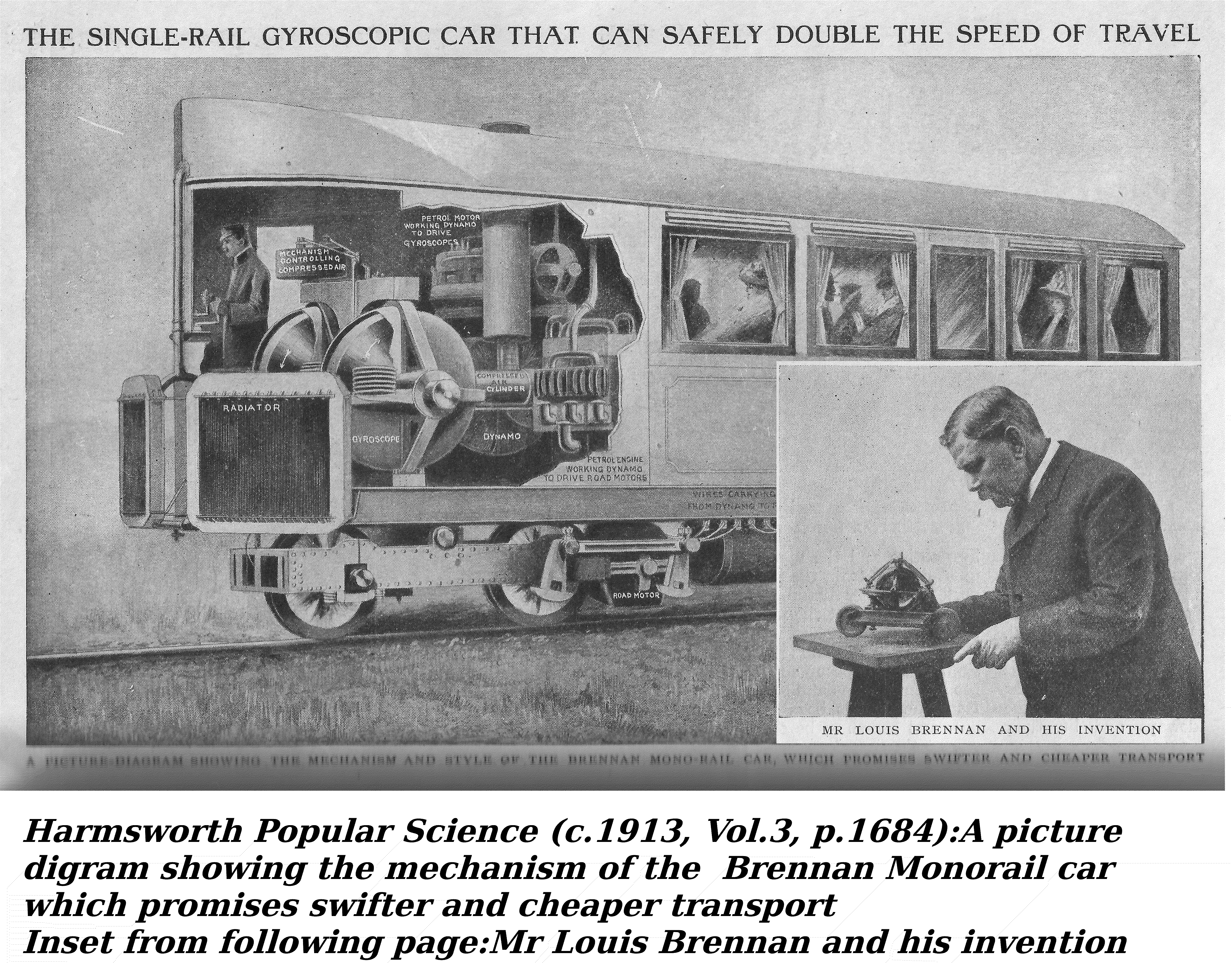

Developed in the early twentieth century, the gyro monorail showed much promise. One version, first created by Irish-born inventor Louis Brennan (28 January 1852 – 17 January 1932) and patented in 1903, first took shape as a small, child-sized train, inspired by a toy Brennan had purchased for his son. This prototype appeared before the Royal Society in 1907. “A scaled-up system,” notes Vintage Everyday, designed for transporting goods and materials, “was successfully demonstrated to the press in 1909 and they loved it, nicknaming it the ‘Blondin railway’ after Charles Blondin, a tightrope walker who had traversed Niagara Falls.”

One of the biggest supporters for the monorail project was Winston Churchill, who solicited practical and financial support from the War Office and from India, supplementing the considerable amount of Brennan’s own fortune that he had sunk into the project. When Churchill came to view it, he remarked, “Sir, your invention promises to revolutionize the railway systems of the world.”

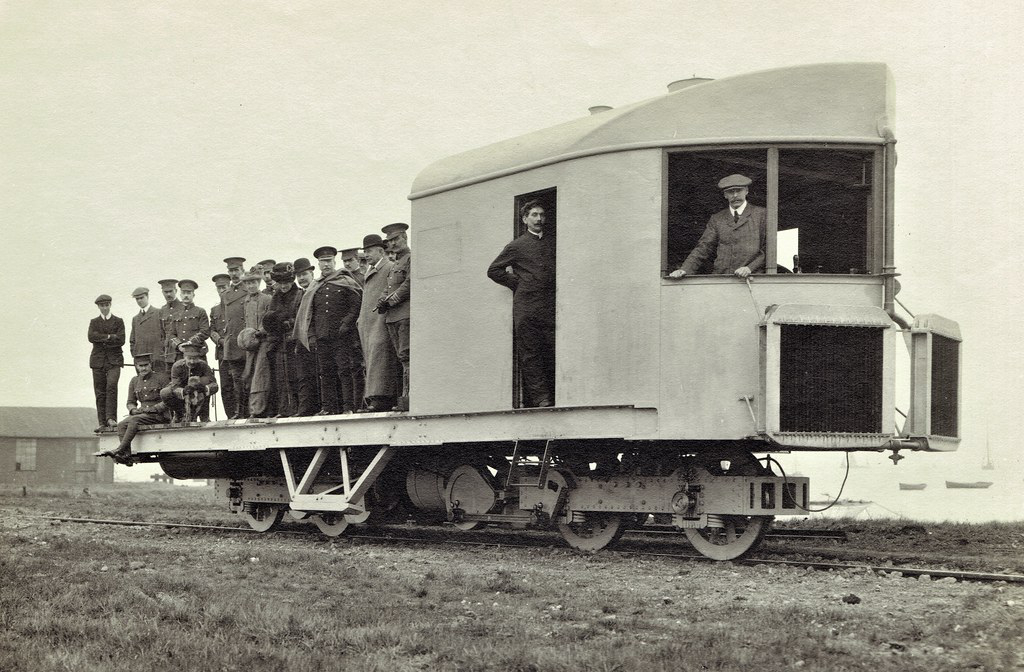

British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith took a ride during the Japan-British Exhibition in London the following year and the monorail won the Grand Prize. A line was proposed for use in an Alaskan coal mine, and it seemed as if Brennan might make his fortune on the design.

But it was not to be. Like so many an ambitious monorail project—including a proposal to build the U.S.’s first suspended monorail system in New York City in 1930 – this one was derailed by fears over long-term stability and pressure from conventional railroad manufacturers. Financing disappeared, and Brennan lost everything.

Over the next several decades, proposed monorail systems were mostly shelved until the development of trains that run on concrete beams instead of railroad tracks – and even then, at least in the U.S., using monorails as alternatives to other forms of transit has mostly been cast as an impractical, utopian idea, fairly or no. Even after two-hundred years of development, “monorails are perceived as new, experimental and untried,” says Kim Pederson, president of the Monorail Society.

Outside of the fully automated monorail system in Las Vegas, city planners in the U.S. tend to associate monorails with theme parks, especially the famed monorails at Disney resorts. Worldwide, however, they have taken off, and for all their retro-futurist baggage, they deserve to be taken seriously again as transportation and transit options.

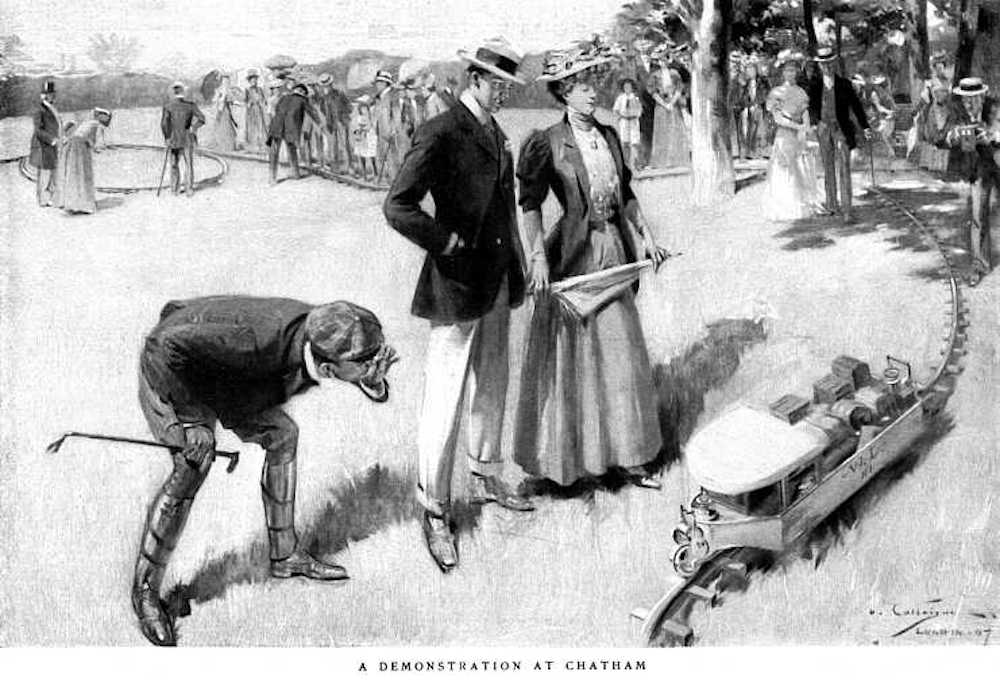

Brendan on the lawn demonstrating his invention

Brennan sprang his gyroscopic mono-rail car upon the Royal Society. It was the leading sensation of the 1907 soiree … the great inventor expounded his discovery, and sent his obedient little model of the trains of the future up gradients, round curves and across a sagging wire… It ran along its single rail, on its single wheels, simple and sufficient; it stopped, reversed, stood still, balancing perfectly. It maintained its astounding equilibrium amidst a thunder of applause… The audience dispersed at last, discussing how far they would enjoy crossing an abyss on a wire cable. ‘Suppose the gyroscope stopped!’

– H. G. Wells, The War in the Air, 1908

By way of added interest, hereunder is a December 1907 report by American journalist Cleveland Moffett (April 27, 1863 – October 14, 1926) for McClure Magazine (volume 30 No. 2) – ‘The Edge of the Future in Science – Transportation and the Gyroscope – Louis Brennan’s Mono-rail Car’ (transcribed by Catskill Archive):

A Demonstration on the Inventor’s Lawn

And now for the test. A dozen of us are waiting on the lawn of Mr. Brennan’s home—railroad men from South Africa, financial men from London, and others. We have had the invention explained to us in a general way, and at last we are to see it.

“Let her go,” says the inventor to one of his assistants, and straightway from beyond the trees a strange little object shoots out and comes gliding toward us. It makes no noise; it shows neither smoke nor steam; it does not bump, it does not sway; it simply comes straight along on its little track over the grass, very smoothly, and flashing in the sun. It is the gyro-car on its mono-rail!

As she comes closer we hear the low hum of her hidden gyroscopes (they will be quite noiseless in the larger model), and are struck by the car’s remarkable width in proportion to her, length. She suggests a trim little ferry-boat, and is utterly unlike any known form of railway car. Now the track curves sharply to the right; she takes the turn with the greatest ease, and leans slightly toward the curve. Now the track turns again, and she glides behind the bushes. Coming out on the other side, she enters bravely on the approach to a mono-rail suspension-bridge, a wire rope stretched over the valley that falls away between two small hills—seventy-odd feet of tight-rope-walking for the little car. Straight across she runs from side to side,—no wavering, no tipping,—and then straight back again as the assistant reverses her; then out to the middle of the rope, where they stop her, and there she stands quite still and true, while the gyroscopes hold her. This is something never yet seen in the world a mass of dead matter, weighing as much as a man, balancing itself unaided on a wire!

Weird Feats of Balancing

Now Mr. Brennan catches hold of the rope and sways it back and forth with the car on it. And at each change of angle she rights herself easily, automatically. The inventor draws back his arm and strikes the car a hard blow on its polished side with his open palm. And the car holds quite steady; she neither sways nor trembles.

“That represents the greatest force of the wind,” he tells us. “There is no hurricane strong enough to blow one of my trains off a track like that.”

Then he lifts one of the weights from the car and bids us note what happens.

“These weights are all measured to a scale, and this one—really about fourteen pounds represents three tons on a full-sized car; I mean it has the same effect on this small car that three tons would have on a large one. Now, look!”

As he spoke he dropped the weight on the very edge of the little model, and the car rose slightly on that side under the sudden load.

“That,” he continued, “was exactly as if forty or fifty passengers in a large mono-rail car had jumped at the same moment from the middle of the car to the extreme edge of it. As you saw, the car simply rose to meet the shock, which is what she would always do speaking, of course, within the limits of safe loading and safe construction.”

To impress us further with the steadiness and safety of the little car, Mr. Brennan ran it back to solid ground and, seating his little daughter in it, he sent her forth upon the rope, ran her across and back, and finally brought her to rest in the middle, with a drop of six or seven feet beneath her. There she sat as calmly and steadily as if it were the most natural thing in the world for young ladies to take the garden air balanced on wire ropes.

After this the assistants switched the car on to a length of gas-pipe lying loose upon the ground, so crooked and full of kinks and sharp bends that it seemed absurd to expect wheels to run over it. But run over it they did, and rapidly, too, picking their way from right to left, up and down, following the crookedest part of the pipe with almost human intelligence, and never making a slip.

“That represents the worst possible railroad-track,” laughed Mr. Brennan, “and you see how the car follows it.”

Next the assistants produced a frame of heavy timbers across which a wire rope had been stretched so that, when the frame was held upright, the rope was parallel to the ground and three or four feet above it. On this rope the car was placed and left to balance itself at rest. Then the assistants, one at either end, moved the frame back and forth, so that the car was first far to one side of the perpendicular and then far to the other side—in other words, so that it had to perform a delicate feat of balancing and self-adjustment or else crash to the ground. And the car did what was expected of it, thanks to the whirling balance-wheels, without the slightest difficulty.

These were the most impressive features of the demonstration, although the car did various other things: it climbed difficult grades of one in five; it ran along the side of a steep hill on a track laid over driven piles; it patiently and accurately followed all manner of turns and curves; it stood still obediently at any point and allowed its heavy load to be shifted as desired. In short, it did more tricks in advanced railroading than any train in the world ever dreamed of, or than any railroad manager would believe possible unless he knew about these Brennan miracles.

After the test Mr. Brennan answered the different questions put to him touching his invention and spoke of its future.

The Size and Revolutions of the Balance-wheels

“How fast do your gyroscope-wheels turn?” inquired one gentleman.

“In the present small car about seven thousand times a minute,” he replied, “but in the full-sized car of commerce I calculate that three thousand revolutions a minute will insure absolute steadiness. You understand that the two gyroscopes are geared together with teeth, so that they must work in phase—that is, at the same rate of precessional rotation.”

“What will be the dimensions of a full-sized car?” I asked.

“Its length will be about two hundred feet and its breadth about thirty feet,” answered the inventor, while our looks of wonder grew.

“And its weight?”

“Perhaps a hundred tons.”

“Without a load?”

“Yes.”

“I suppose there will be several such cars in a train?”

“Yes, five or six.”

“And you think you can balance five or six cars weighing a hundred tons each without passengers or freight, on a single rail?” put in a South African official.

“I know I can. You have seen what the model does. Well, the full-sized cars will do the same, only better. I am now building, with government aid, a trial car, forty-five feet by twelve, that will carry two hundred passengers with absolute ease and steadiness.”

“What will be the size of the gyroscope-wheels in your full-sized cars?” questioned another gentleman.

“About four and one half feet in diameter.”

“And their weight?”

“They will weigh about two tons each, or four per cent. of the car’s total mass, which is allowing a wide margin of safety. I think one or two percent will ultimately prove sufficient. And this weight of the gyroscope-wheels will be more than saved by lightness of construction made possible by lessened strain on the cars.”

Brennan’s son demonstrates the monorail

Suppose the Wheels Should Stop!

Mr. Brennan then dwelt on the enormous advantages of a single-rail system in the matter of lessened friction and side-thrusts and the consequent superiority in speed and smooth running—all of which was readily granted by the railway experts, who also agreed that a train would run securely on a single rail so long as the gyroscope-wheels kept turning. But suppose something happened to these? Suppose one of them stopped or both of them stopped? Then what would become of a hundred-ton car poised on a single rail and suddenly deprived of its balancing power?

“As you may well suppose,” replied Mr. Brennan, “that is a matter that I have considered carefully. Suppose the electric power that drives these wheels were suddenly cut off. Do you know what would happen? Nothing. Because the wheels revolve in a vacuum, and on such perfectly poised bearings, with such ideal lubrication, that—even with the driving power cut off—they would continue to turn, by their own momentum, for two or three days, and for two or three hours they would turn with sufficient energy to hold the car safely balanced. That is, they would turn long enough of themselves to provide for any reasonable emergency.”

“Then each car in a train would be balanced by its own balance-wheels?” asked some one.

“Of course.”

“Suppose something went wrong with your lubricating-device?” suggested an engineer.

“I have provided an automatic signal to warn the engineer of such danger, at notice of which he would at once run the train into a safety siding. There would be many of such sidings with dwarf walls to support the cars, or the sides of the cars might slightly overlap the walls.”

“That is all very well,” persisted the South African, “but suppose one of the gyro-scope-wheels did absolutely stop—broke loose from its bearings, or anything you like; suppose it stopped instantly before the train could possibly reach a siding. ‘Then what?”

“Unless the car chanced to be on a curve at that precise moment, the other wheel would hold it steady.”

“But suppose the car was on a curve? Or suppose both wheels stopped suddenly?”

Mr. Brennan smiled.

“Then there would certainly be an accident, just as there is when a boiler bursts or an elevator falls or an automobile gets in a smash-up. I do not claim that my mono-rail system does away with danger. I only claim that through lessened friction and lessened strain, which means lessened chance of accident and derailment, my system involves less danger than our present methods of railway transportation.”

There followed some talk, more or less technical, about the actual construction of a mono-railroad, with details as to the weight of rails, the length of ties, the best way of laying tracks along a stony mountainside, and much about grades and pile-driving and concrete foundations. The South Africans were becoming practical; and they were interested to know how these mono-rail cars would come to rest in vast, sparsely settled regions, where they might be used for pioneer or military work, and where there would certainly be no safety sidings to support them. Mr. Brennan explained that, in such cases, the cars would be provided with adjustable legs that could be let down on either side when the gyroscopes were not in use.

Finally, the hour having advanced, the company departed for London, deeply impressed with what they had seen and heard. I, however, was honored with an invitation to stay for further talk, and, in the course of the evening, Mr. Brennan pictured for me the wonderful things that are to result from his invention.

And here I asked many questions. Would all of his cars be pointed fore and aft like the model? Oh, no; only the front and rear cars would be pointed; the others would be oblong, but vestibuled together, so that the train would look like a great transatlantic liner, without masts or smoke-stacks. And the cars would be built of enameled steel, with windows flush with the sides, and all the surfaces free from projections and smooth as a bird’s wing, so as to give the least possible resistance to the air in swift flight.

“Six cars two hundred feet long,” I reflected. “That makes a length of twelve hundred feet for your vestibuled train?”

“Exactly.”

“And a width of thirty feet?”

“About that.”

“And a weight of a thousand tons—counting the load?”

“At least.”

“All balanced on a single rail?”

“Yes.”

I was silent awhile. What could one say to a picture like that?

“What power will drive these great trains?” I finally asked.

“Any power you like—steam, electricity, gasolene. The gyroscopes will balance the train as well with one as another.”

“And such trains will cross wide rivers like the Hudson and the Mississippi?”

“Of course, if bridges are there.”

“How about speed?”

“In speed we shall surpass all that the world has known; for with friction reduced to a minimum and side-thrusts practically eliminated, there is no reason why our mono-rail trains should not make one hundred and twenty, one hundred and fifty, or even two hundred miles an hour with absolute steadiness and far more safety than is possible on existing trains. I may add that ideal smooth running will be secured by having a continuous line of wheels under each car, a single line, of course, so that the whole train will rest on a solid chain of wheels.”

To San Francisco in a Day

“Two hundred miles an hour!” I said. “That will mean the run from New York to San Francisco in a single day?”

“Easily. And pleasantly, too; for you must bear in mind that these cars will be different from any cars thus far known. They will not be cars at all, but great, beautiful parlors, where we shall travel almost without knowing that we are traveling; where we shall find the comforts and luxuries of a first-class hotel, brilliant dining-rooms like saloons on the best ocean liners, spacious libraries and smoking-rooms, entertainment-rooms for music or dancing, and, of course, large, well-ventilated sleeping-rooms instead of the wretched bunks behind dusty curtains.”

“All that,” I reflected, “because these trains will be wide and not narrow, as a train must be that runs on two rails.”

“Exactly. You see, the gyroscope will balance a wide train as well as a narrow one, and what we gain by that fact in comfort of passengers and facilities for carrying large quantities of freight is beyond calculation. Our trains will have all the advantages of a great steamship and none of the disadvantages.” “On a single rail,” I added. “Yes,” said he.

Louis Brennan was born in Castlebar, Co Mayo, in 1852. He died after he was hit by a car in Montreux and was later buried in St Mary’s cemetery in North London.

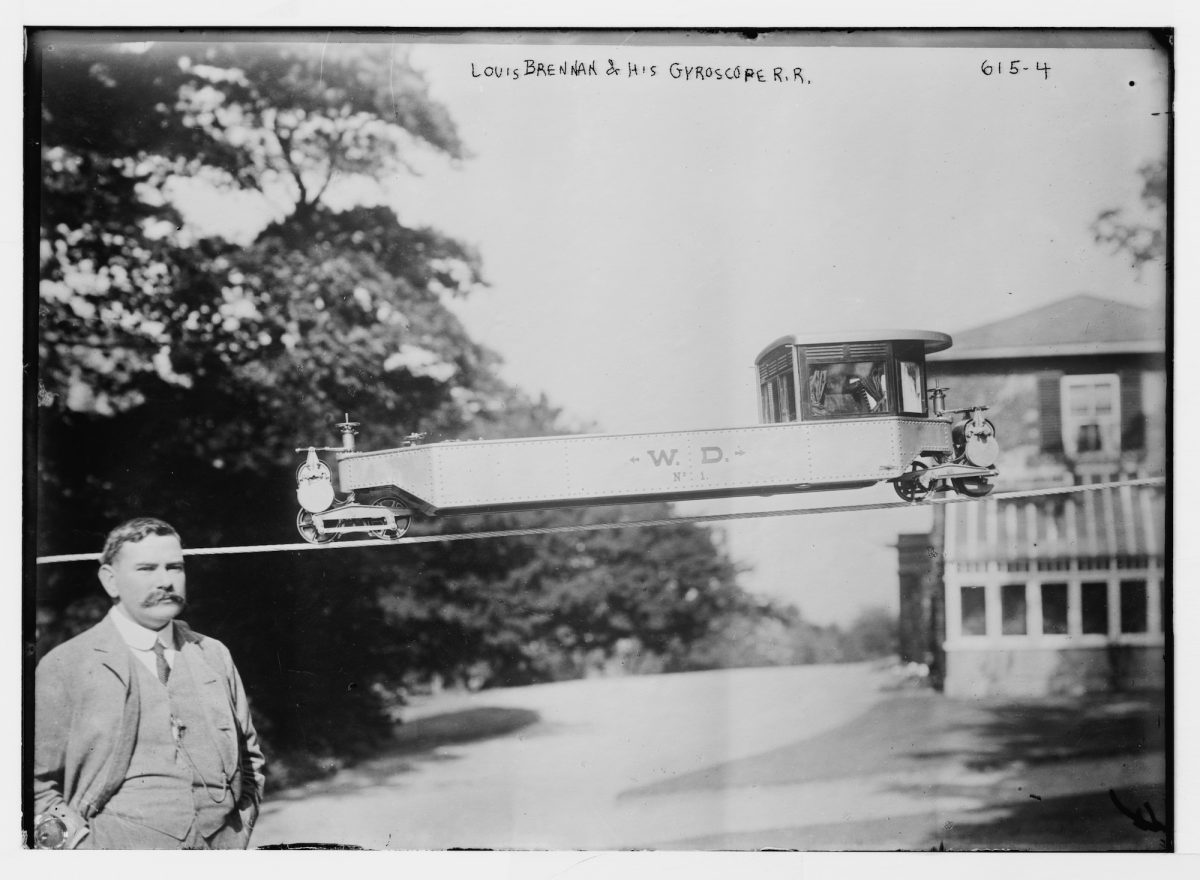

Lead image: Official photo of the Brennan Gyro-Monorail. It was forty feet long and weighed 22 tons, and was designed to carry ten tons The railcar was balanced by two vertical gyroscopes mounted side by side, and spinning in opposite directions at 3000 rpm. Each gyroscope was 3.5 feet in diameter.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.