If history were truly judged, no one would make ROI their top metric for success—certainly not in the arts, where failures so often lead to legacies (which is why artists generally make such bad businesspeople). It’s impossible to predict how inspirational a creative endeavor will be to future generations, even if no one’s paying attention at the time. Take Blade Runner, a film panned on its release which ended up setting the tone for all sci-fi to come. Take Moby Dick, a novel that almost caused Melville to quit writing when it failed with readers and critics. And take the Haçienda, or FAC 51, the legendary nightclub that lost its owners millions, and ended up largely responsible for the “Second Summer of Love,” among other things.

You know the story, or a version of it, if you’ve seen 24 Hour Party People. New Order—or rather, their manager Rob Gretton—opens a club with Factory Records’ Tony Wilson in 1982. From the start, it’s a financial disaster. Huge cost overruns plague construction. Malachi Lui at Analog Planet sums up a few typical issues after its opening: “Staffers stealing beer crates every night. £5000 in cash misplaced and incinerated by New Years’ Eve pyrotechnics. A lighting engineer stealing equipment for his own rental business. Seemingly endless tax problems.” This list could go on and on. But so too could the list of seminal bands and events. Early gigs by New Order, the Smiths, OMD, and Cabaret Voltaire, just to start.

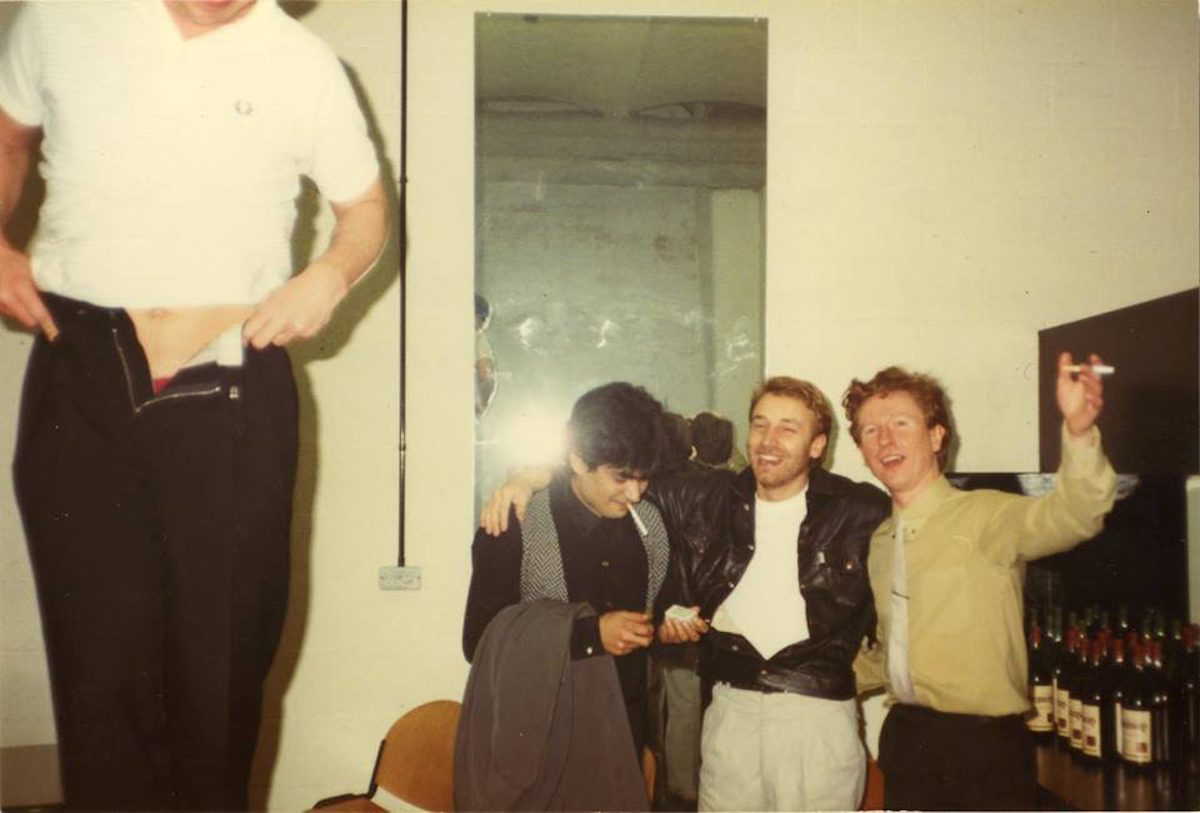

“FAC 51 in its early years focused on booking bands months before they blew up,” even if those shows “almost always filled less than a quarter of the club’s capacity.” The shows are legendary; the nights’ receipts, not so much. A transition in the mid-80s to DJ nights did not improve its fortunes, but soon “the club became the home of acid house and Ecstasy,” notes Vice, “and gave birth to bands like The Stone Roses and The Happy Mondays. Pretty important place then….” I’d say. “The Haçienda was a magnet for musicians, music fans and all manner of creative types,” writes Dave Haslam at the Vinyl Factory. It changed the way nightclubs looked and helped launch the careers of rave giants like 808 State and The Chemical Brothers before finally shuttering in 1997.

The Haçienda’s fifteen-year run is one of Manchester’s most significant musical legacies, as essential to pop culture as CBGBs. Peter Hook’s purchase of the name further strained his awful relations with the rest of New Order, and as for who to believe about the Haçienda’s failures, it’s impossible to say. But Hook’s 2009 book, The Haçienda: How Not to Run a Club (coming to TV!), offers many insights on its rise and fall. Hook himself tells Vice, “you just can’t really do business like that anymore. Look what happened the first time around: financial fucking black holes and villains all over the place.” Ah, yes, but also….

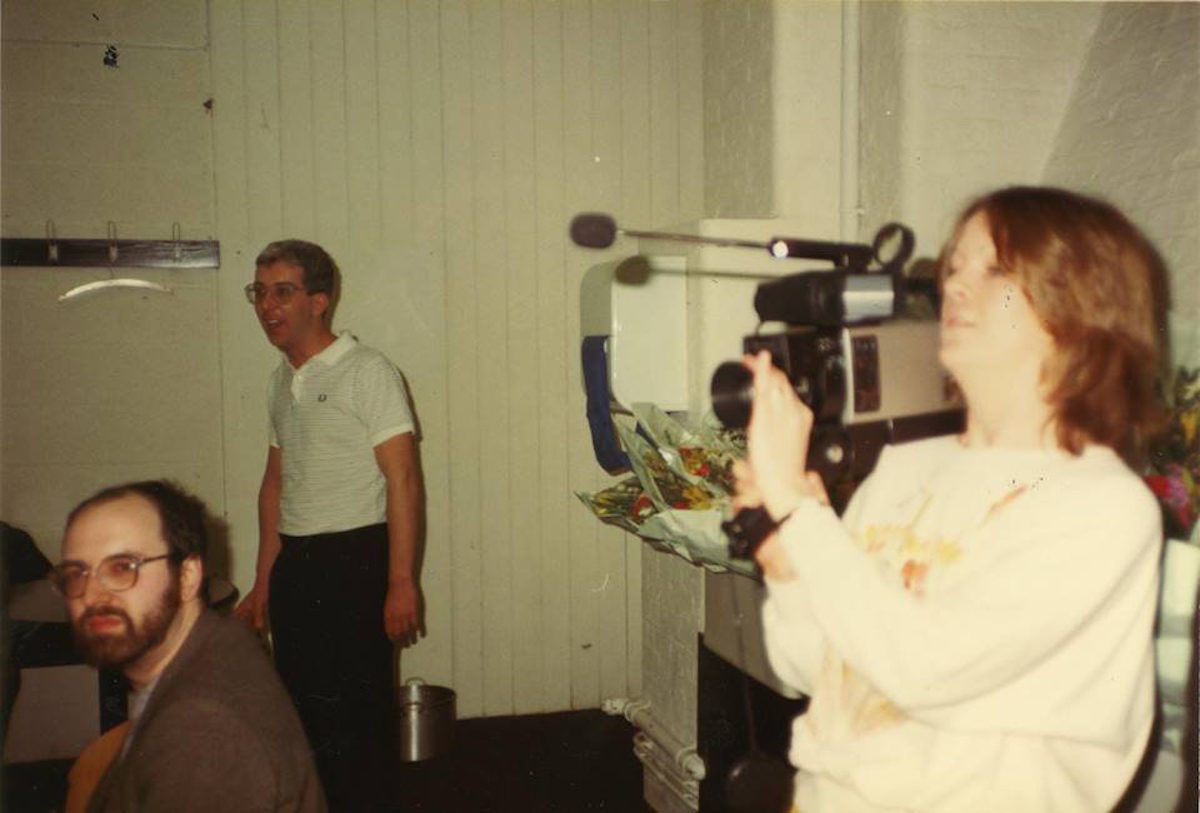

Maybe it’s a real shame the business end of things won out over the creative. What might it have been like to stand on the threshold of such a fertile creative history? As an account from club designer Ben Kelly suggests—along with pictures from the grand opening—it didn’t look like much at the beginning.

People turned up not really knowing quite what to expect and I guess also because when it first opened, and for the first few months, it took a long time to settle into what it eventually became. It was open almost every night of the week, but the people that came along weren’t necessarily the hippest bunch of people. They were a very straight looking bunch of people, all very conventional looking, drinking pints of beer.

Things eventually picked up. “People made it their own,” Kelly writes. “They felt like it was somewhere for them. That’s the great thing about a place, if you feel some sense of belonging. Not ownership, but it is in a funny way partly yours, you can relate to it, and relate to the people.” Kelly designed the club as a “three-dimensional manifestation of the Factory ethos,” and it came to represent that fully in the early 80s. “It was called the Hacienda, that was kind of mysterious, and it had a number and the bar had a name, the Kim Philby bar and there was another called Hicks, and so there was a narrative and all these things that were stitched into it that gave intrigue and interest. It was completely unique.”

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.