Dr. Harold “Doc” Edgerton (1903-1990; MIT electrical engineering professor from the 1930s until his death in 1989) turned the stroboscope into a conduit for beautiful images. His multiflash photographs made the invisible visible. By stopping time we could see the unseen.

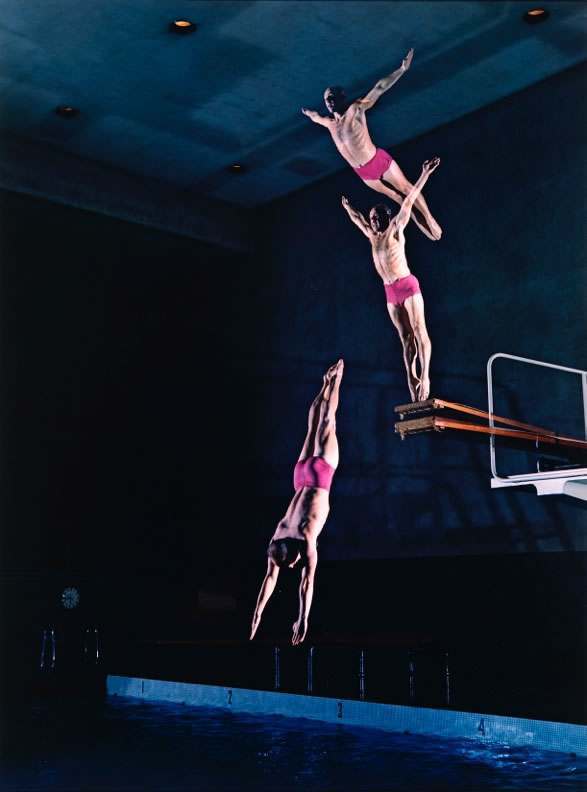

The strobe light equipment advanced the work of such visual pioneers as Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey. Flashing up to 120 times a second, the device enabled Edgerton to photograph subjects that were too bright or too dim or moved too quickly or too slowly to be captured with traditional photography.

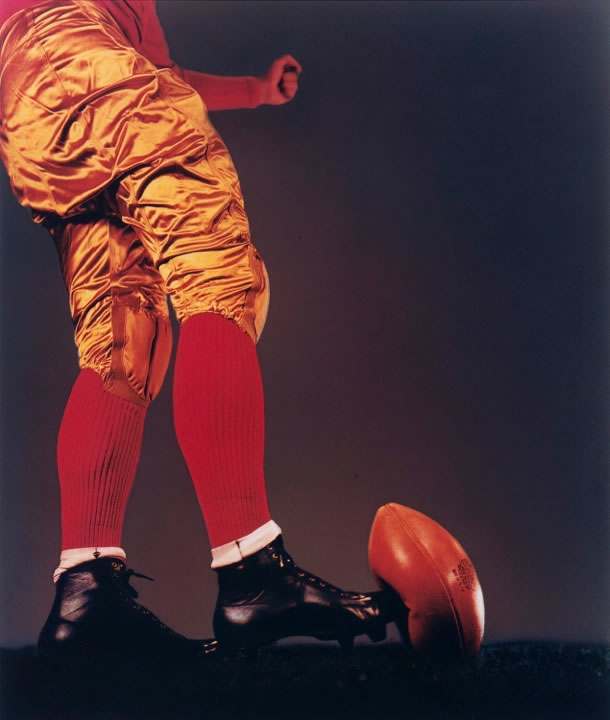

In the early days of his career, Edgerton’s subjects were motors, running water and drops splashing, bats and hummingbirds in flight, golfers and footballers in motion, his children at play. By the time of his death at the age of 86, Edgerton had developed dozens of practical applications for stroboscopy, some that would influence the course of history.

The strides that Edgerton made in night aerial photography during World War II were instrumental to the success of the Normandy invasion and, for his contribution to the war effort, Doc was awarded the Medal of Freedom. During the Cold War, Edgerton and his partners at EG&G made it possible to document nuclear explosions, an advance of incalculable scientific significance. In the last three decades of his life, Edgerton concentrated on sonar and underwater photography, illuminating the depths of the ocean for undersea explorers such as Jacques Cousteau, who dubbed his good friend “Papa Flash.” – Massachusetts Institute of Technology

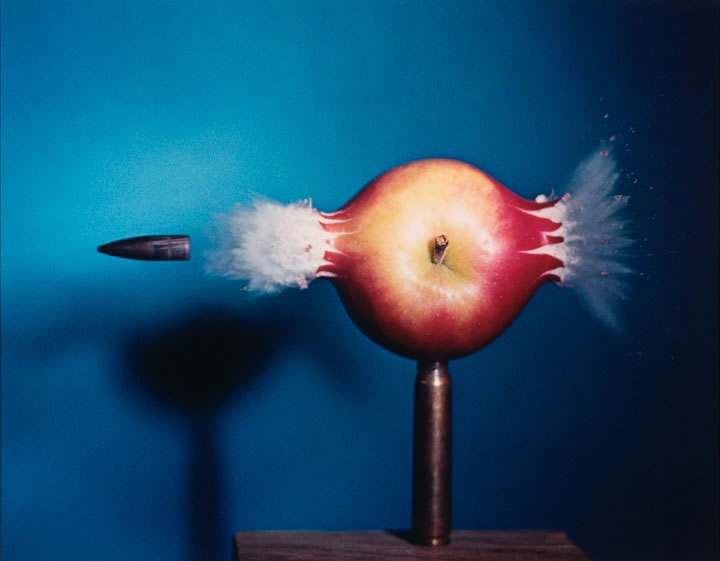

This startling image is one of a series of pictures that Edgerton took throughout his career of bullets being shot through apples. The most famous one (see HEE-NC-64002) was used to illustrate a lecture he gave in 1964 entitled “How to Make Applesauce at MIT.” Moments after the apple is pierced by the .30 caliber bullet, it disintegrates completely. What is so surprising is that the entry of the supersonic bullet is as visually explosive as the exit. The duration of the flash in this photo is about 1/3 microseconds. The amount of light given off is small enough that the exposure must be made in total darkness. To trigger the flash at the proper moment, a microphone, placed a little before the apple, picks up the sound from the rifle shot, relays it through an electronic delay circuit, and then fires the microflash.

In 1937 one of Edgerton’s milk-drop photographs was included in the first photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

With permission of The Etherton Gallery

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.