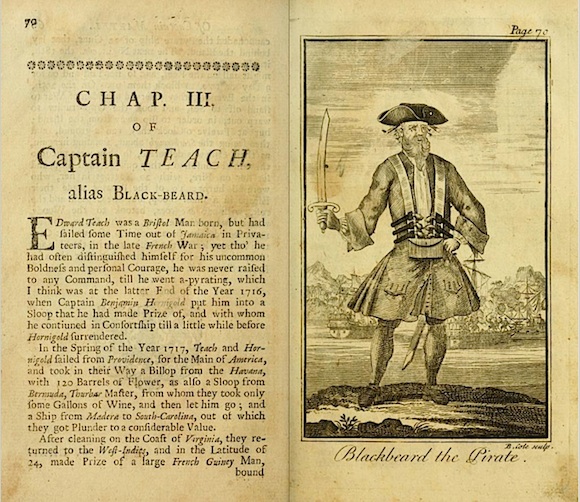

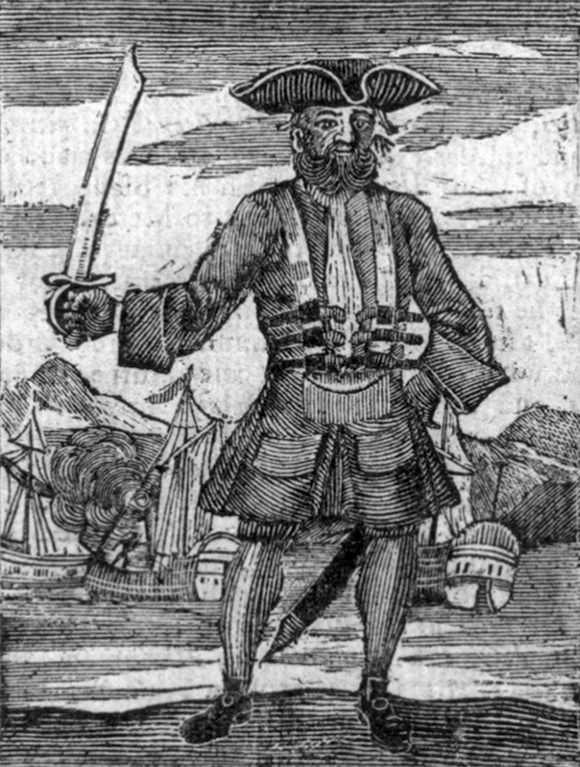

“The skull and crossbones was too much of a cliche. In a book from Foyle’s in Charing Cross Road I found the drawing of the pirate Blackbeard, Captain Teach, with his arm holding a Saracen sword” – Malcolm McLaren, 2008.

Over the spring and summer of 1980, the late Malcolm McLaren worked with the themes and theories underpinning the concepts for a new retail environment and fresh fashion direction from their base at 430 King’s Road in west London’s World’s End.

Disillusioned with the pedestrian punks who had started to frequent Seditionaries in the wake of the Sex Pistols split in 1978, the outlet was routinely shuttered. “Apart from a few t-shirts, we didn’t come up with any new designs in four years,” Westwood later said.

The pair’s investigations in 1979 and 1980 crystallised around Westwood’s production of a billowing garment based on an 18th century shirt pattern from the historian Norah Waugh’s 1964 study The Cut Of Men’s Clothes 1600-1900.

McLaren had already introduced notions of music industry-provoking audio piracy into his work with the newly-formed Bow Wow Wow – who released their cassette-only debut single that summer – and pounced upon the shirt’s promisingly unstructured silhouette.

“I could see it being worn as a dress by the young paramour of a pirate captain, romping around his quarters with his belt, one of his waistcoats and a pair of his sagging buckled boots,” McLaren said in the mid-00s. “I rejected the rest of Vivienne’s ideas but kept the shirt, to which I added the vision of pirates to give a certain look, style and pop panache. We then built the Pirate collection around it.”

The choice of the garment is noteworthy. According to Waugh (who had lectured at London’s Central School Of Art and run the costume department at the dramaturg Michel Saint-Denis’ London Theatre Studio in the 30s), men’s tailoring did not start in Britain until the end of the 18th century; prior to that “men’s clothes had a distinctly dressmaker quality”.

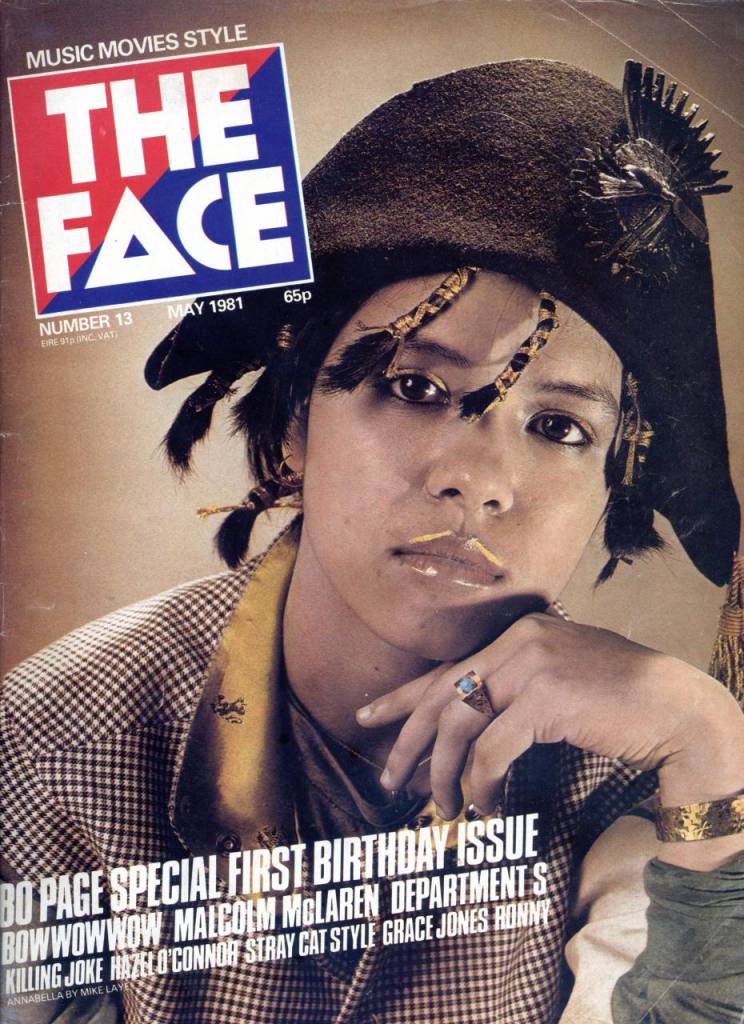

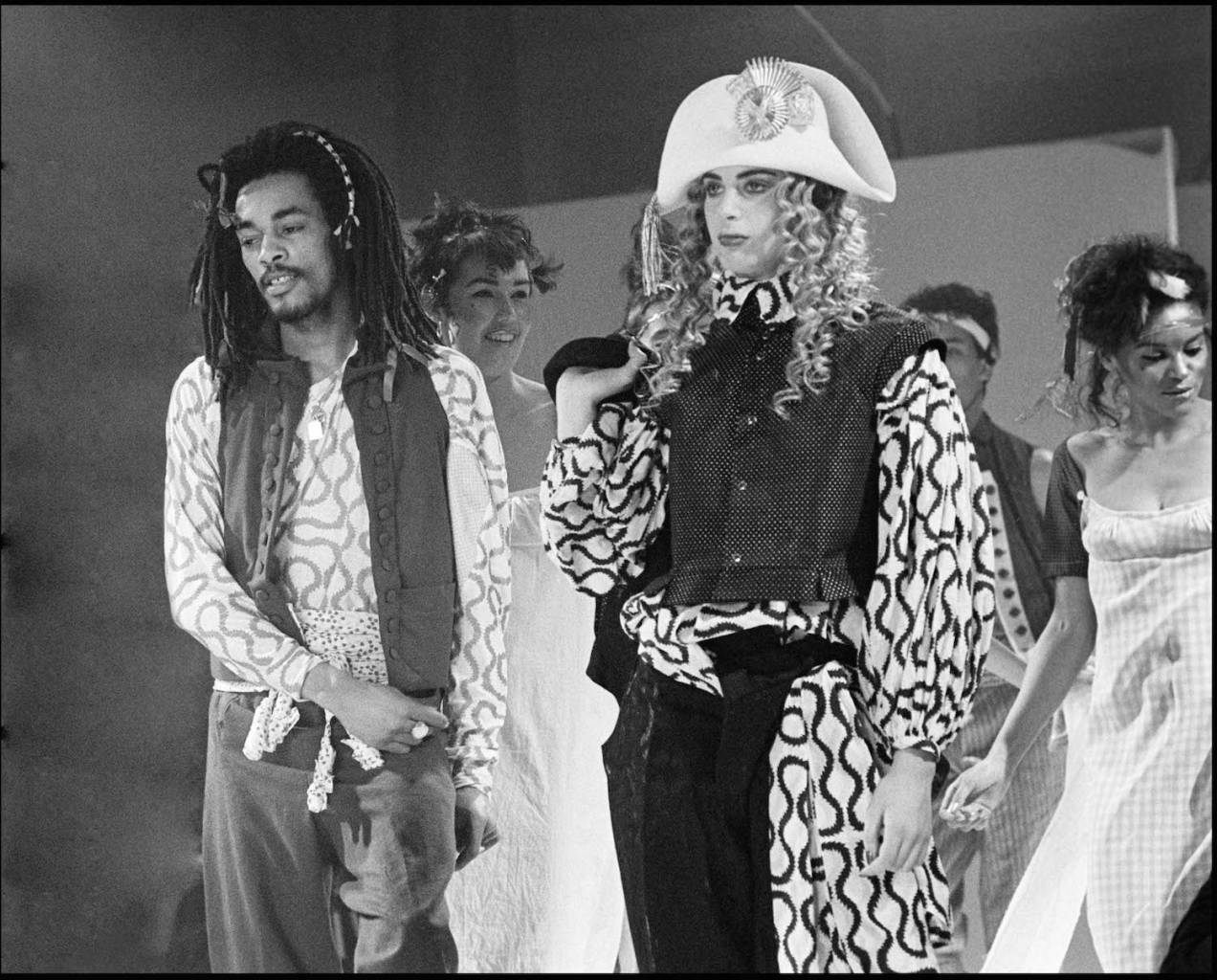

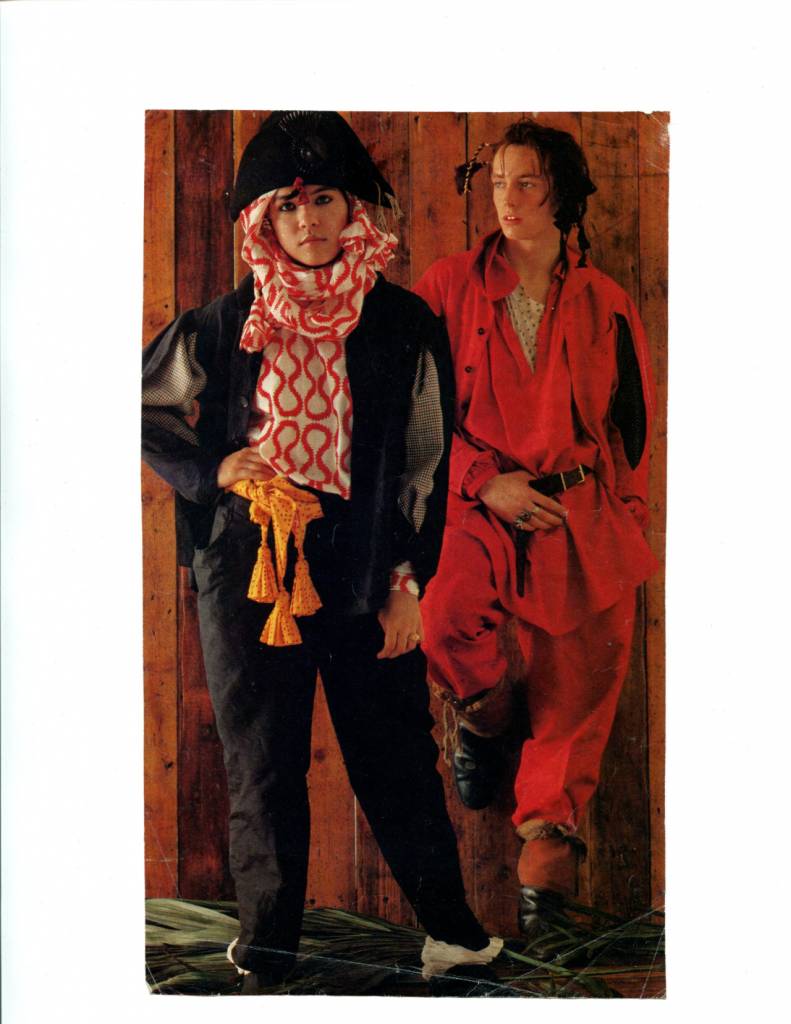

Annabella Lwin and Matthew Ashman from Bow Wow Wow in Worlds End Pirate clothing designed by Vivienne Westwood & Malcolm McLaren, 1981 Via

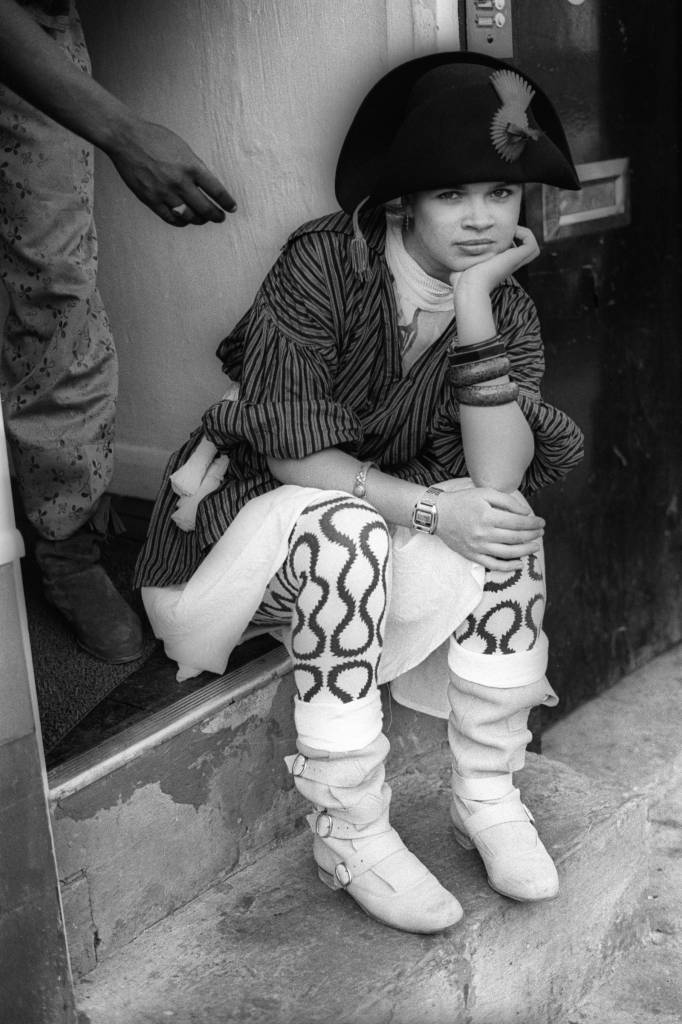

Lizzie Tear in McLaren & Vivienne Westwood’s Pirate look sits outside Worlds End shop, Kings Road, Chelsea London 1980

By rejecting two centuries of fashion progress – just as they had rejected the pop culture developments of the 60s with the establishment of Let It Rock in 1971 – and fusing the results with the utterly contemporary, McLaren and Westwood once again moved into unexpected territory with clothing which struck a chord outside of fashion and music.

The Pirate shirt makes the cover of UK Vogue, May 1981, the first issue to celebrate the new spirit of romanticism exemplified by the public fascination for royal bride-to-be Lady Diana Spencer. Photo: Alex Chatelai

Worlds End self-striped Pirate dress matched with petty-drawers and stockings on the female model in this shot from the spread Escape To The Sun, UK Vogue, May 1981. Photo: Alex Chatelain

McLaren’s choice of name for the new iteration at 430 World’s End came from the final destination on the front of the 31 bus; the last stop on the route was Limerston Street, just a few yards west of McLaren and Westwood’s shop.

“The thought of the world ending, the apocalyptic, suggested to me the potential for cultural change,” said McLaren in 2008. “I thought Worlds End (note absence of apostrophe) could do that by having a clock that went backwards around not twelve, but thirteen hours – something impossible to conceive. Something unreal. Something magical.

“Worlds End was meant to represent a pirate galleon setting sail out of this muddy hole called England, a place I had learned to loathe by then due to the conditions I had to meet because of the English courts and the music industry generally.

“Vivienne wanted to destroy and not have anything further to do with Punk. She hated it. So, this store became a way of sailing away from the Kings Road. I wanted the store to ‘float’ as on waves. The little windows in the front were to create that part of the galleon where the captain would often have his chambers.”

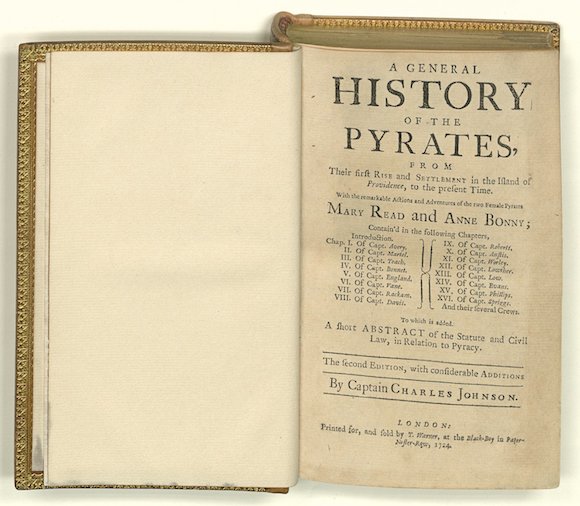

When developing a logotype and label ident for the new collection, McLaren resorted as ever to research. At Foyle’s bookshop he came across a copy of A General History Of Pyrates, the highly entertaining 1724 volume by Captain Charles Johnson which is attributed to Daniel Defoe. The author of Robinson Crusoe, one of McLaren’s favourite books, Defoe had lived not far from where McLaren was born in Stoke Newington.

Famously Defoe was pilloried in 1703 for seditious libel over his satirical pamphlet The Shortest Way With Dissenters; it was this archaic charge which inspired the name McLaren gave to 430 King’s Road in 1976.

One of the chapters of the Johnson book is dedicated to the exploits of Edward Teach, the notorious Black-Beard The Pyrate whose appearance excited McLaren’s interest: “The beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravagant length…and was accustomed to twist it with ribbons, in small tails. In time of action he stuck lighted matches under his hat which burned slowly at the rate of about 12 inches an hour.

“Appearing on each side of his face, his eyes looking naturally fierce and wild, made him altogether such a figure that imagination cannot form an idea of a Fury from Hell to look more frightful. In the commonwealth of Pirates he who goes the greatest length of wickedness is looked upon with a kind of envy amongst them.”

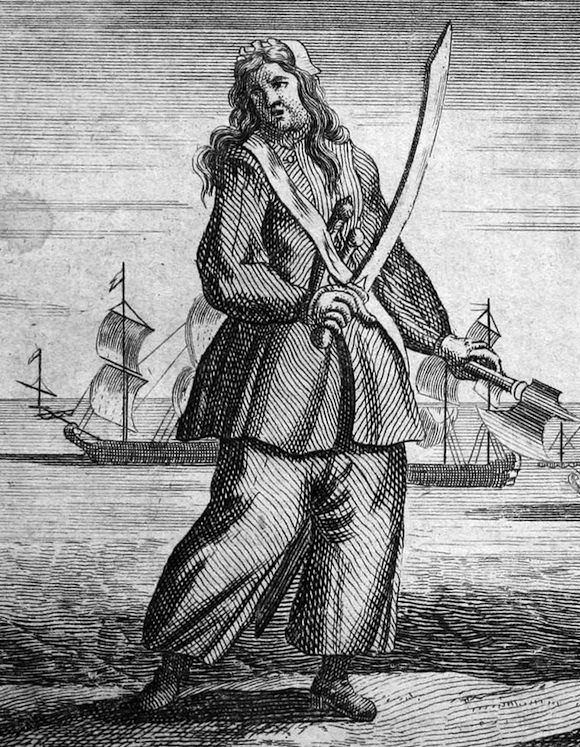

In the illustrations by Benjamin Cole, the fearsome figure is shown with one muscular arm holding a Saracen sword, a weapon also favoured for its deadly properties by the likes of the infamous Anne Bonny.

As McLaren/Westwood afficianado Stuart Swift has pointed out, the logo was taken directly from the flag of another subject of A General History Of Pyrates: the privateer-turned-pirate Thomas Tew, who traded in gold, silver, jewels and slaves and is alleged to have founded the Madagascan pirate colony Libertalia (where he appointed himself Admiral). While Blackbeard’s story fascinated McLaren, the pirate’s standard – the skeleton of the devil raising a toast as he pierces a heart – lacked the impact of Tew’s.

This symbol of romantic rebellion was then applied to labels, brooches and even the clock spinning backwards outside 430 King’s Road when Worlds End opened at the end of 1980.

Johnson’s book also produced a name for the first Worlds End collection; a vessel commanded by these desperate men and women is designated “the Pirate”, as in: “I followed their advice and went on board the Pirate…” This is why the clothing produced by McLaren and Westwood in the first part of 1981 is grouped under the singular.

Watch the BBC’s 1985 documentary To The World’s End – about the great lost 31 bus route – here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.