Beyond Our Ken

FX: Night, wind in trees, an owl hoots, horror music slowly builds.

Announcer: In last week’s episode, our grizzled hero Rod Thrust, played by Kenneth Williams, escaped from the gruesome flesh-eating twins, Betty Marsden, and fled into a dense thick forest, played by Bill Pertwee, while a gibbous moon, Hugh Paddick, glared down. But soon, Rod heard the terrifying sound of something grim and brutal hunting him down. There was a fetid stinking breath panting hard on his flesh. Getting ever closer. He ran faster but his legs would not move. Suddenly he fell on to the ground. He turned and looked up and saw the hideous deformed face and blood shot eyes of a ravenous monster staring down at him. There was no humanity there, just the disgusting smell of the grave. Saliva drooled from its mouth which opened to reveal tombstone yellow fangs ready to bite. The beast stooped and said…

Kenneth Horne: Hello, my name is Kenneth Horne…

Cue: Music, FX, audience applause.

Kenneth Horne: Well, hello and a warm welcome to another episode of Round the Horne. But before we continue, I’ll just give you the answers to last week’s quiz. The first answer was, of course, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The second, six-and-half inches or three in cold weather. And the third was through a string vest. Unfortunately, not many of you got that one and what Mrs Formica Plankton of Luton suggested is not physically possible.

Now, the other day, I was out and about when I chanced upon a shop in Mincing Lane…

Hugh Paddick (off): Bold…very bold…

Kenneth Horne: …a small shop called Bona Films.

FX: Door opening, bell rings.

Kenneth Horne: Hello, is anyone there?

Hugh: Oh hello, my name’s Julian and this is my friend Sandy.

Kenneth Williams: Bona to vada your dolly old eek.

Kenneth Horne: Hello, I’m Kenneth Horne…

Kenneth W.: Of course you are, Mr Horne, I didn’t recognise you with your clothes on…

Kenneth Horne: Ah, you mean from when I visited Bona Saunas..?

Hugh: That’s right.

Kenneth Horne: How is the sauna business?

Hugh: Oh, we gave that up.

Kenneth W.: No business, you see. Nada. None. Nanti.

Hugh: We only had the one client…and that was you…

Kenneth W.: …And you only had a stiff neck…

Hugh: …Terrible disappointment..

Kenneth Horne: Yes, it’s still a bit stiff now…

Hugh: Oh he’s bold, isn’t he bold, Sand?

Kenneth Horne: So, what is it you’re doing now?

Kenneth W.: Well, Mr H, we are doing the Bona Films, you see, which is your actual films for the Bona market.

Kenneth Horne: And are you working on something just now…?

Hugh: Go on, tell him, Sand, you tell him, go on.

Kenneth W.: Well, Mr. H. we are hoping to make your actual film with your actual Ken Russell…

Kenneth Horne: Does he know…?

Hugh: Oh, he’s sharp…Doesn’t miss a trick…

Kenneth W.: Well, no not yet. But he will know once we find an opening for him.

Kenneth Horne: I’m sure you will. So, what sort of film is it?

Hugh: Well, it’s your actual movie about art.

Kenneth W.: Tchaikovsky.

Kenneth Horne: Bless you.

Kenneth W.: No, no, the composer, Tchaikovsky..

Kenneth Horne: Oh, I see…

Hugh: The grand pianist…

Kenneth Horne: Say no more…

Kenneth W.: Oh, get him…

Hugh: Oh, yes, he was this big omi-palone, with lovely luppers, and fab lallies, and this gorgeous riah all down his back.

Kenneth W.: Lush.

Kenneth Horne: And which one of you is going to be play Tchaikovsky?

Hugh: Oh, no, that part’s taken.

Kenneth W.: Yes, Doctor Kildare’s got it.

Hugh: Mucky cow.

Kenneth Horne: So, what part will you taking?

Kenneth W.: Oh no dear, we’re not in it, we’re just there to ogle Dr. Kildare’s lovely dish.

Distraction

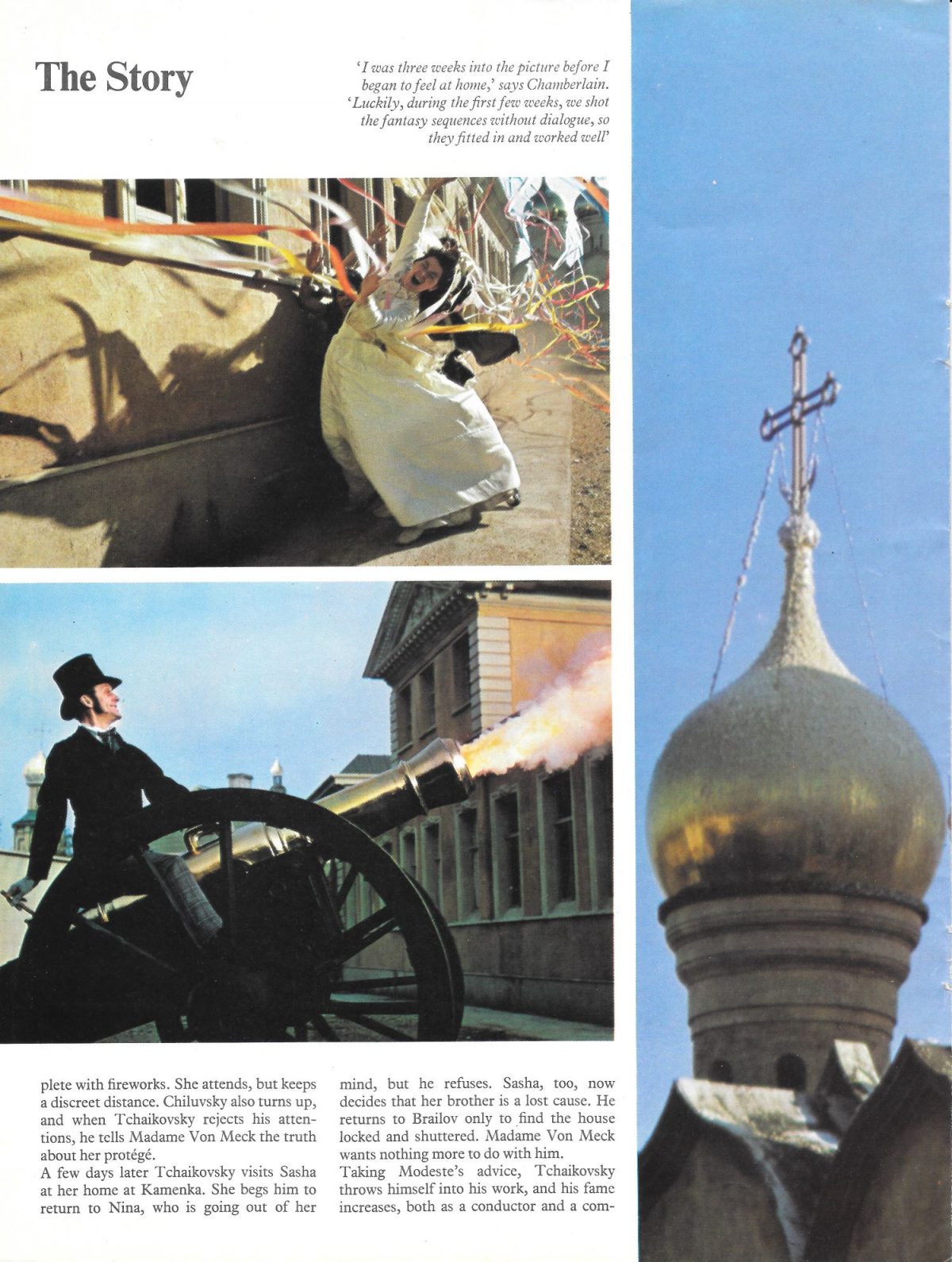

Ken Russell had a trick to encourage actors to perform more naturally. In the run through before a take, Russell would focus his attention on one of the props before shouting, ‘Who put that bloody chair there?’ The actors stopped while the props crew looked-out a replacement chair. Just as the actors relaxed, Russell said ‘Right, we’ll go for a take. Turn over. Action.’

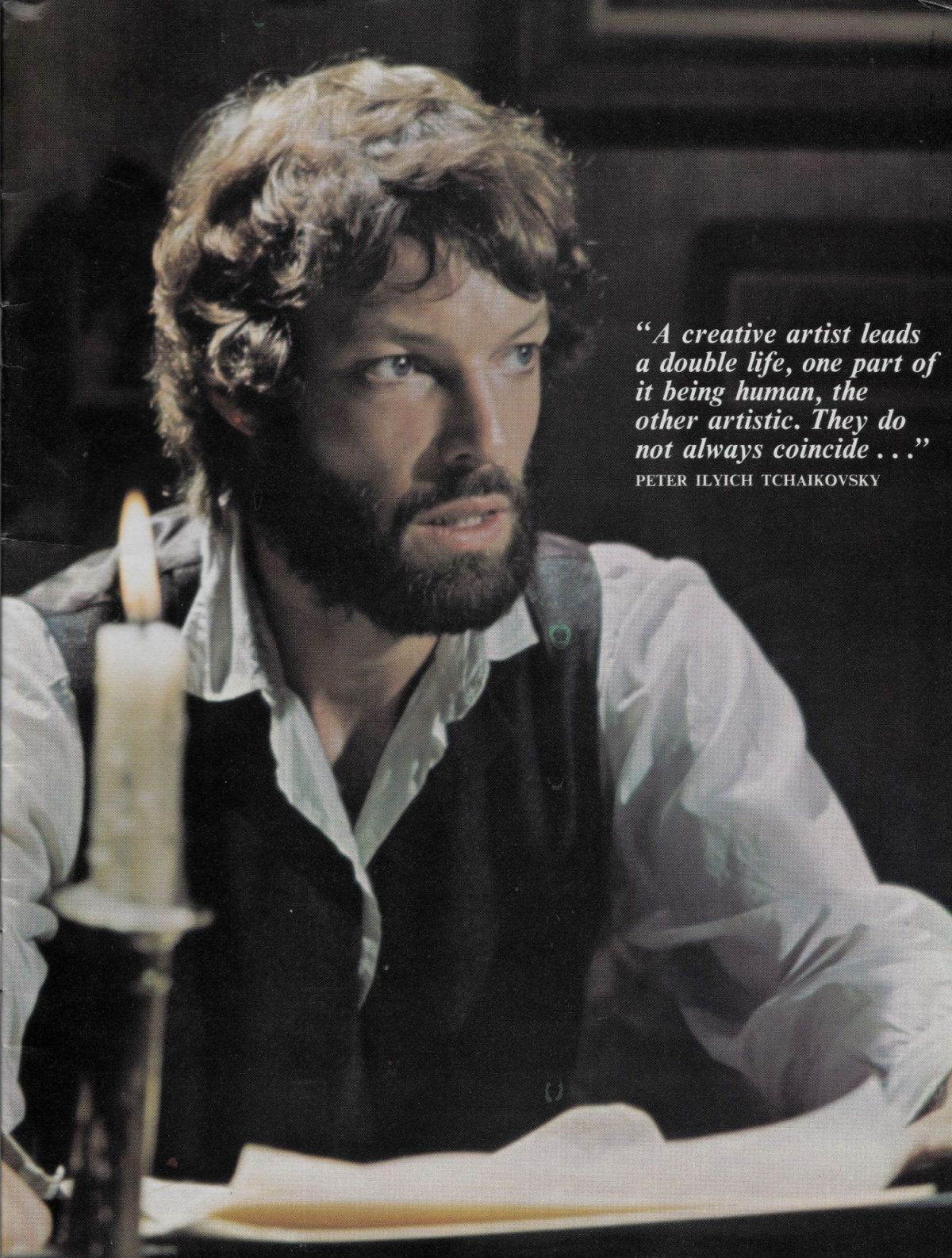

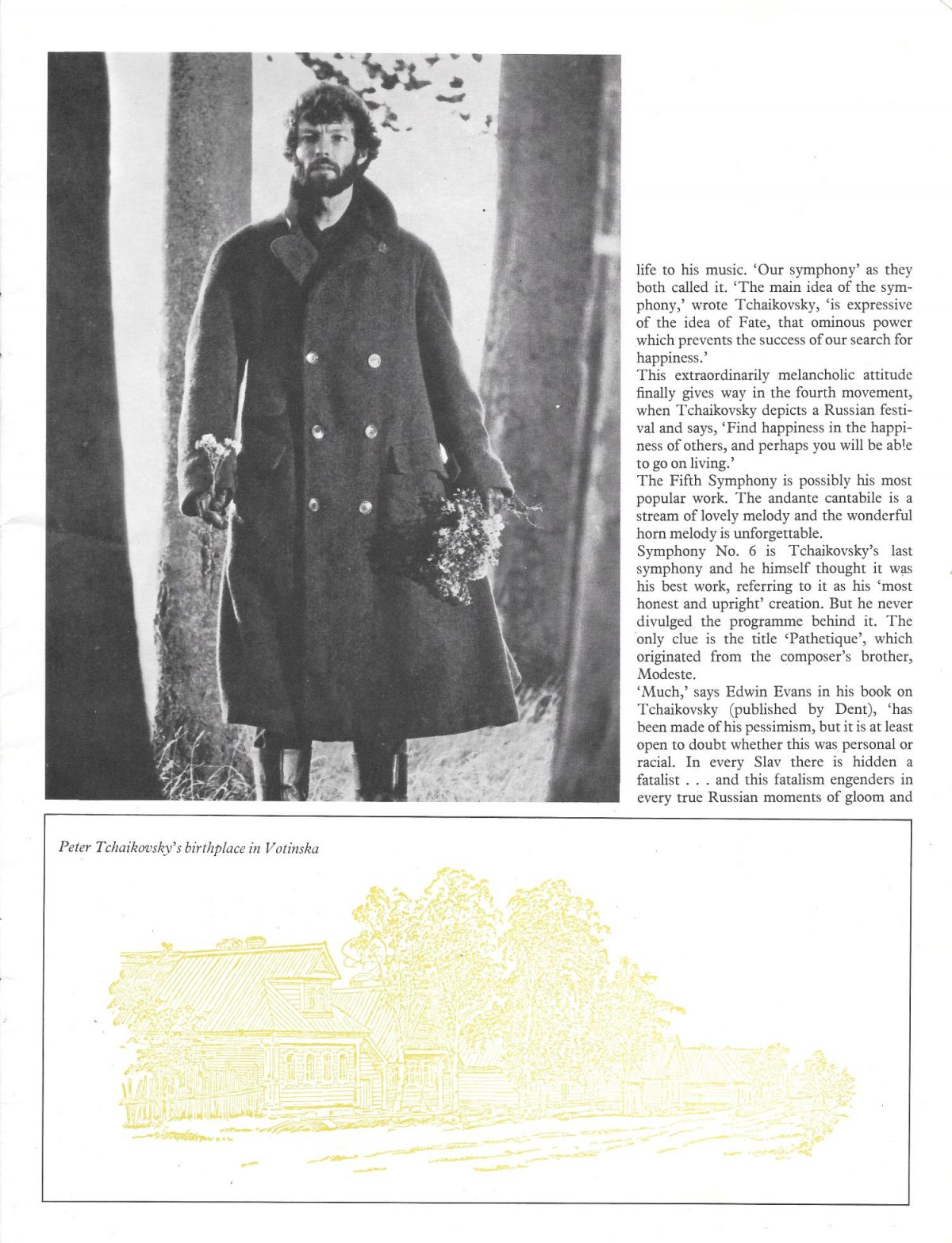

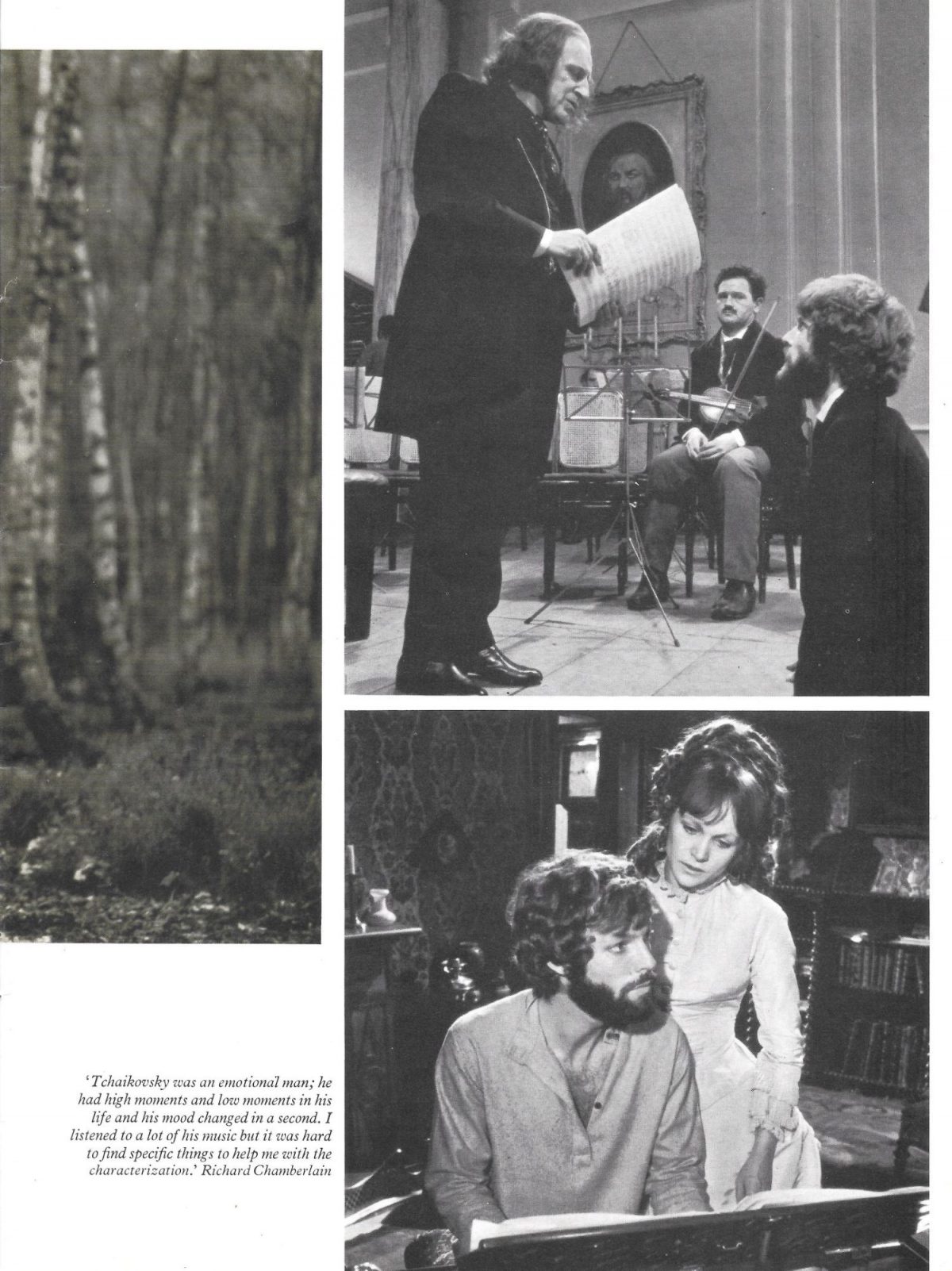

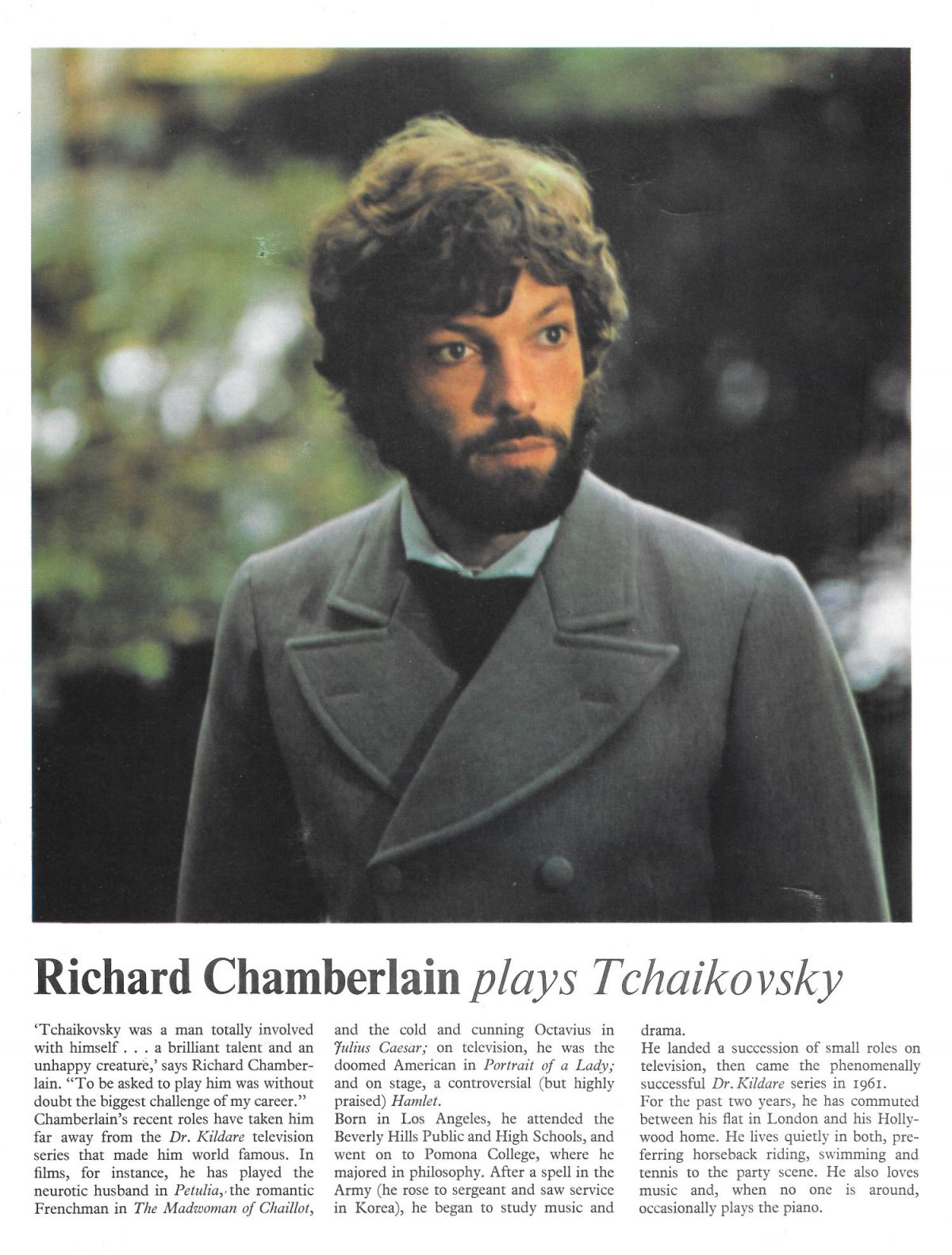

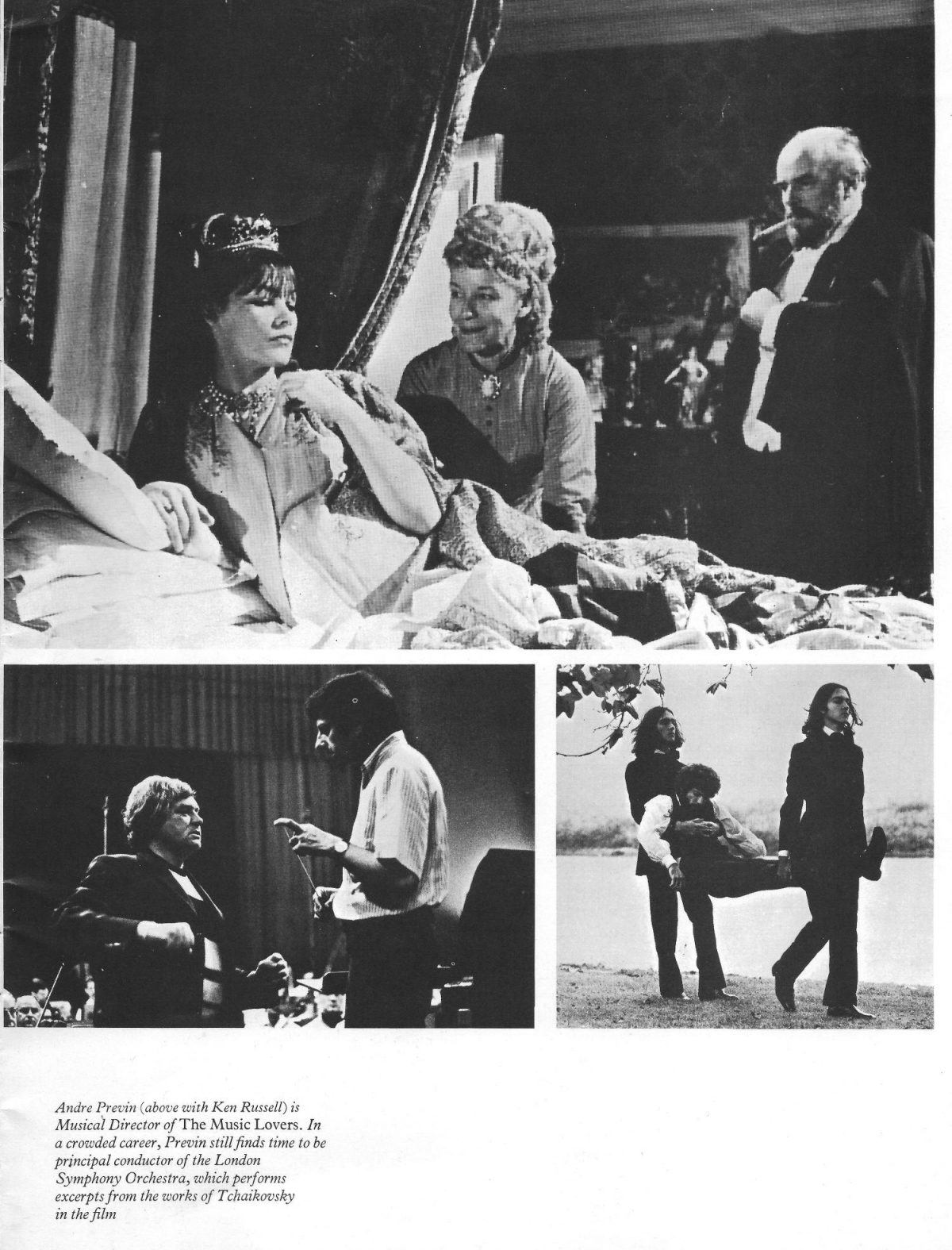

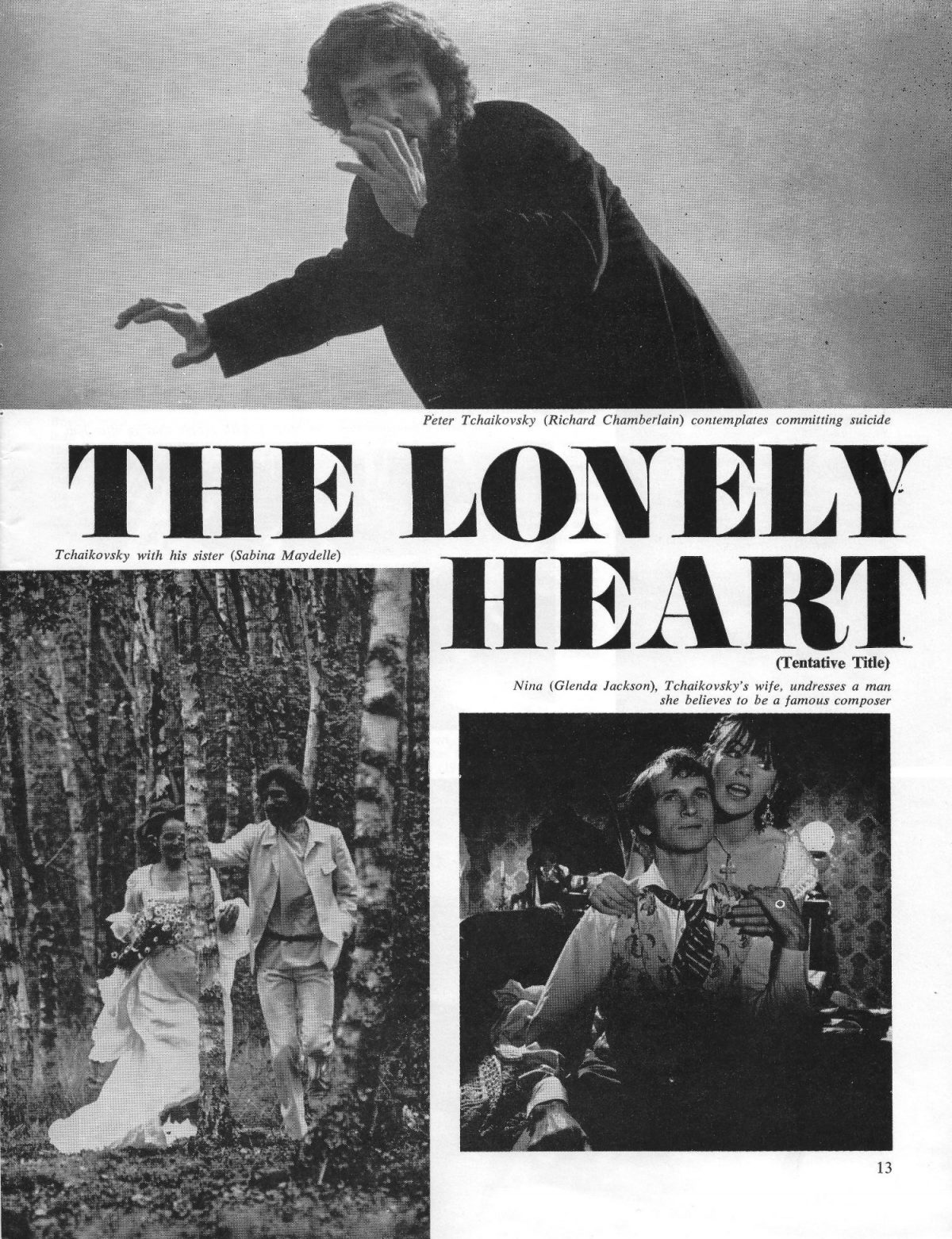

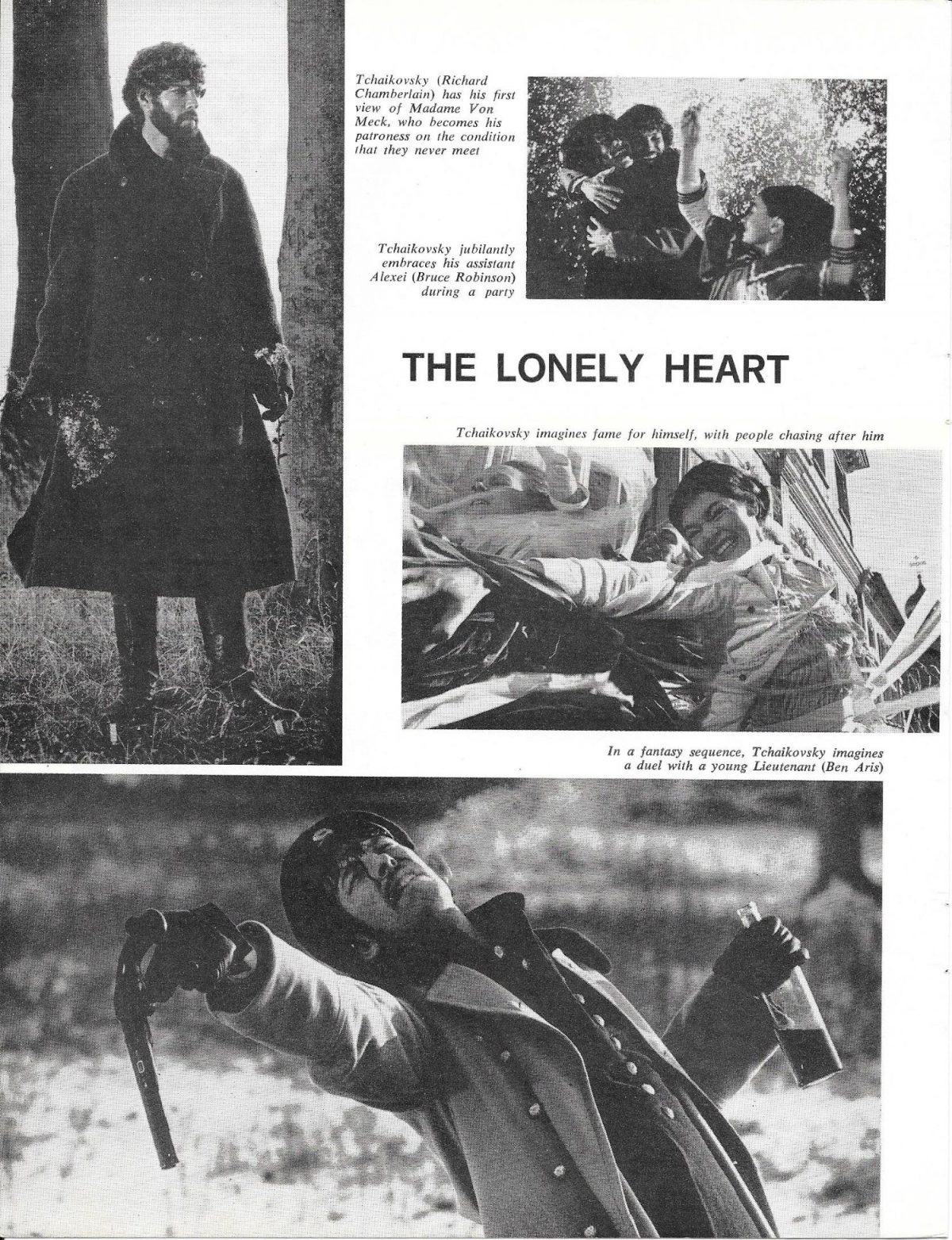

When the former TV heartthrob Richard Chamberlain starred as Tchaikovsky in Russell’s The Music Lovers, he said Russell was not an “actor’s director” but that he created the atmosphere by which actors thrived.

Russell agreed. His intention in creating a distraction was to shake the actors out of their pre-conceived notions of what they were doing.

Suddenly a chair is more important than they are, and while they’re still off-balance I start shooting, so they have to go to their natural reactions. Since they know the story well enough I get something extra out of them I wouldn’t have got if I hadn’t made the fuss about the chair.

It’s not that I’m kinky for chairs; it could have be anything–an item o clothing, a mistake made by the camera crew, anything, as long as it can create a tension, an atmosphere, a charge of electricity.

The Pitch

At the turn of the century, there was a new method of pitching TV programmes to commissioning editors. It was called elevator pitching. The rep from the production company would join the editor in an elevator and have until they reached the top floor to pitch an idea. If it was a good idea, then the rep stayed in the elevator and was deposited back on the ground floor. If it was a no-no, the rep had to walk back down.

The idea was to come up with a programme idea which could be condensed into one sentence. This is now called “tweet pitching”. It’s an idea movies have had for decades. For example, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito are Twins. Or, Alien: it’s Jaws in outer space.

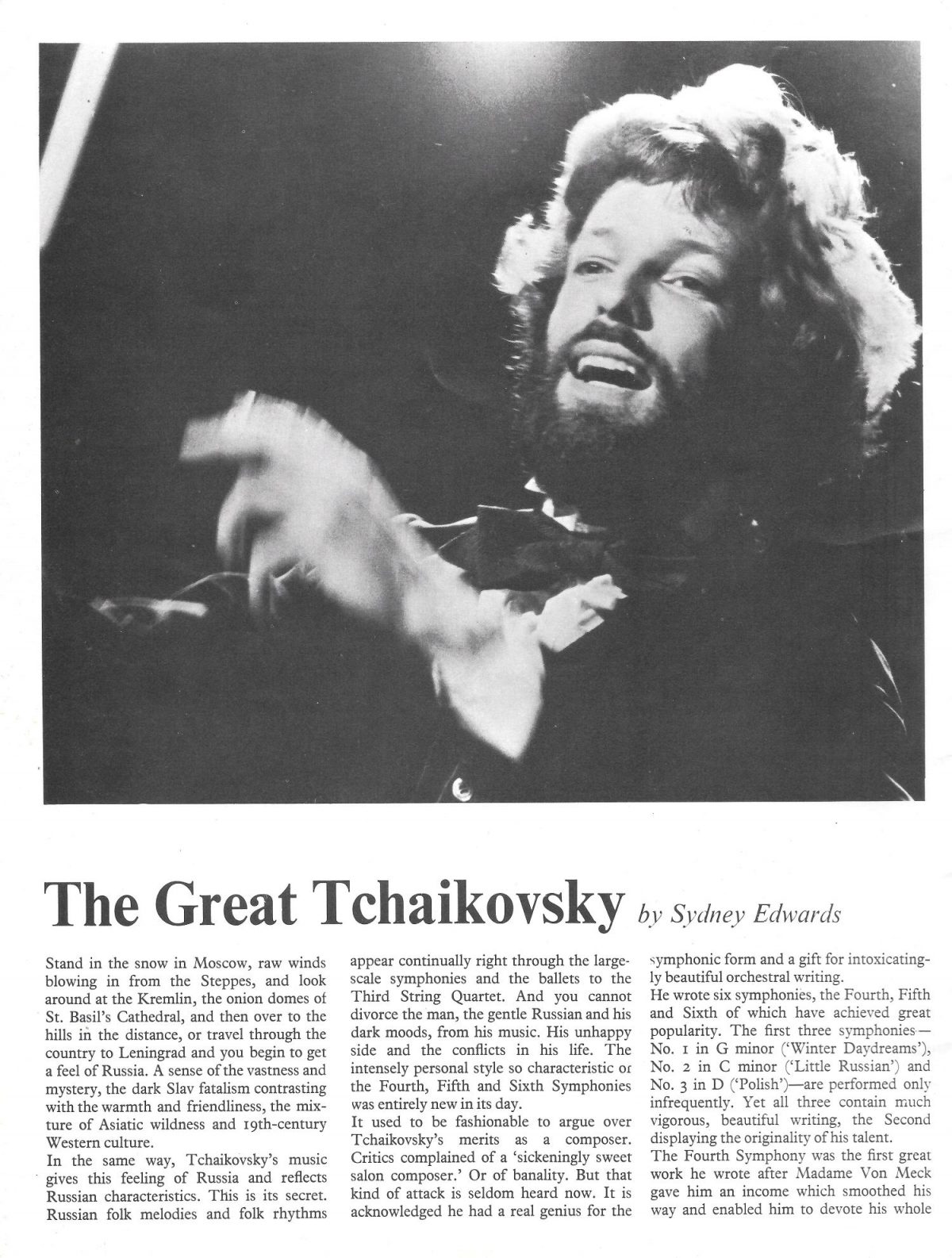

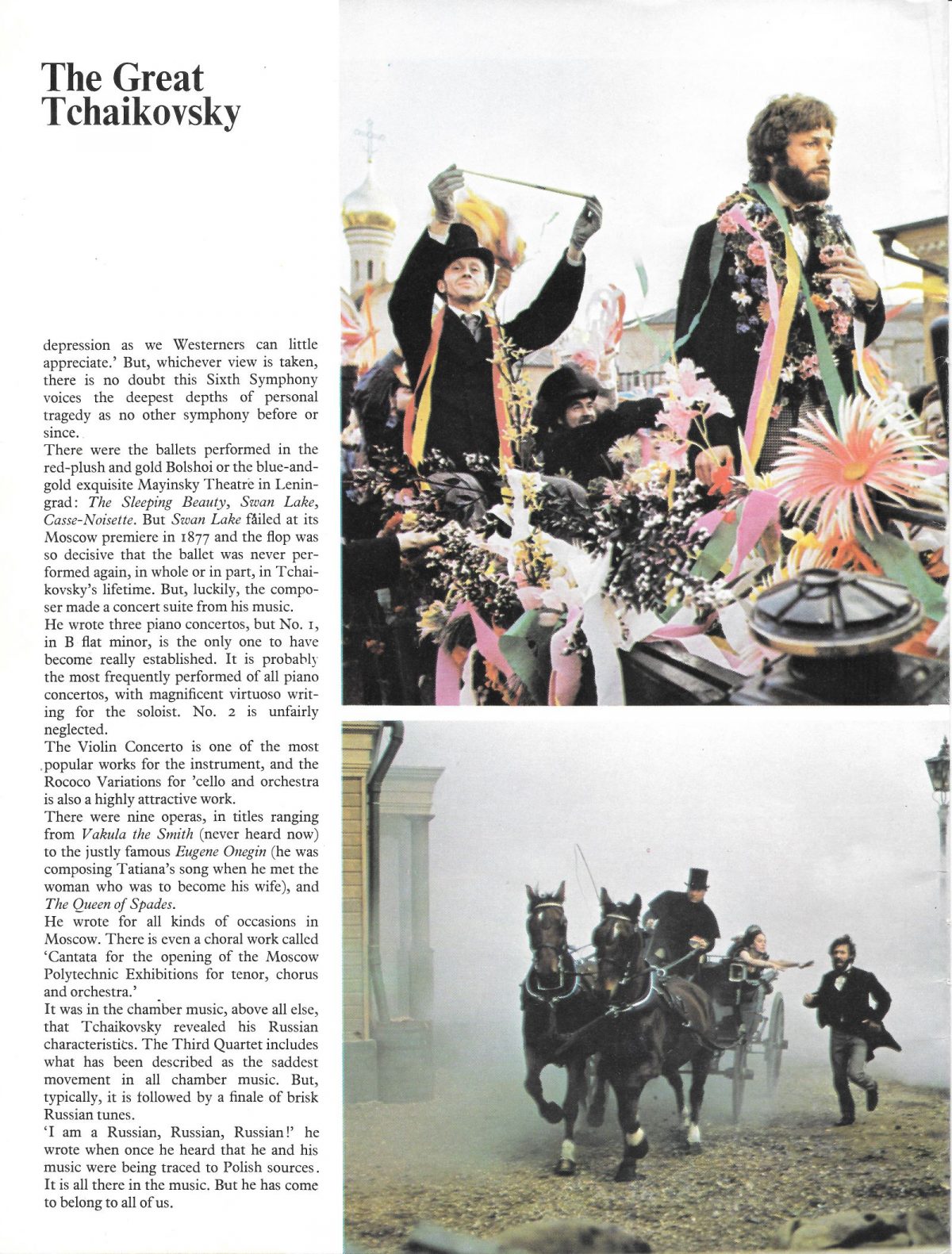

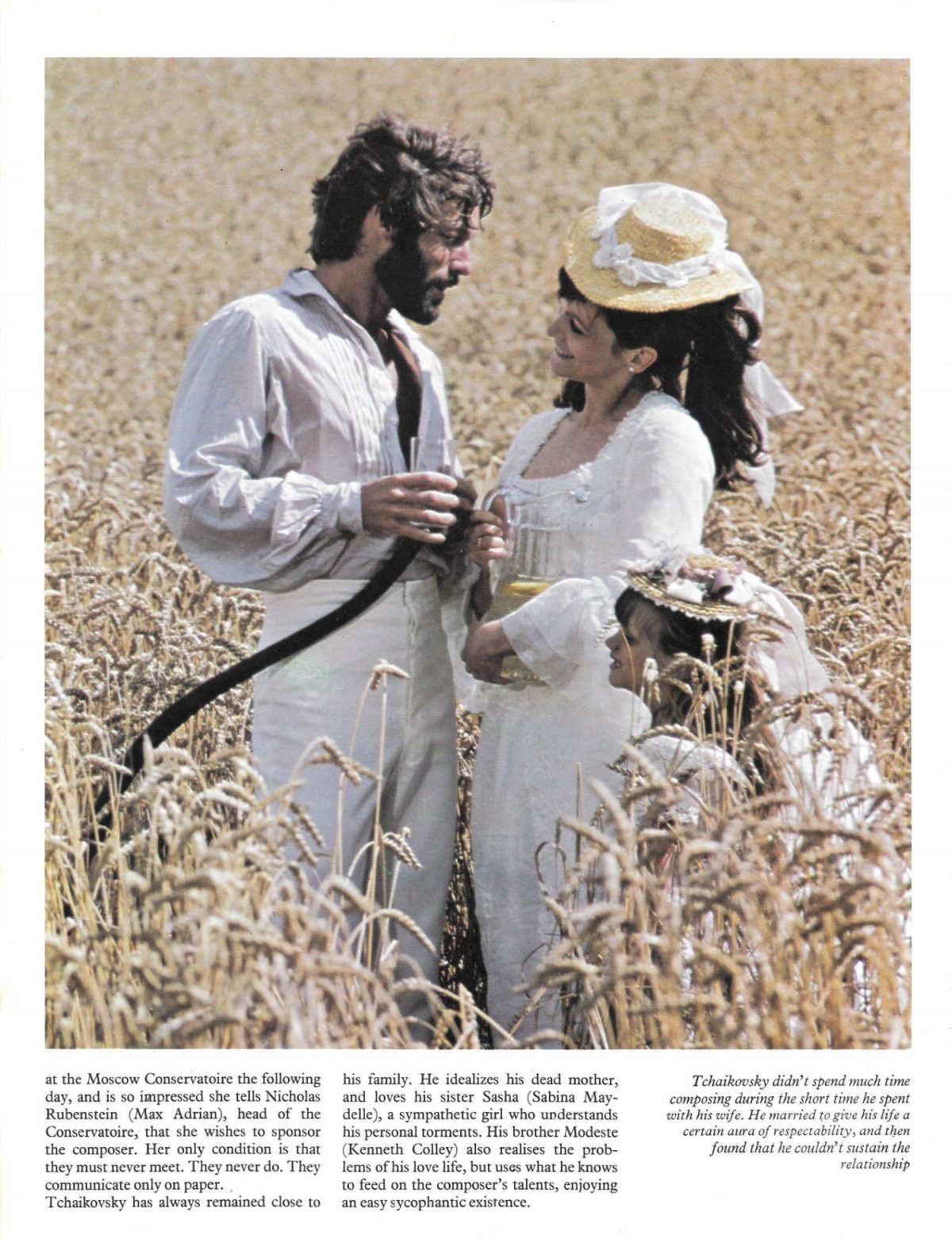

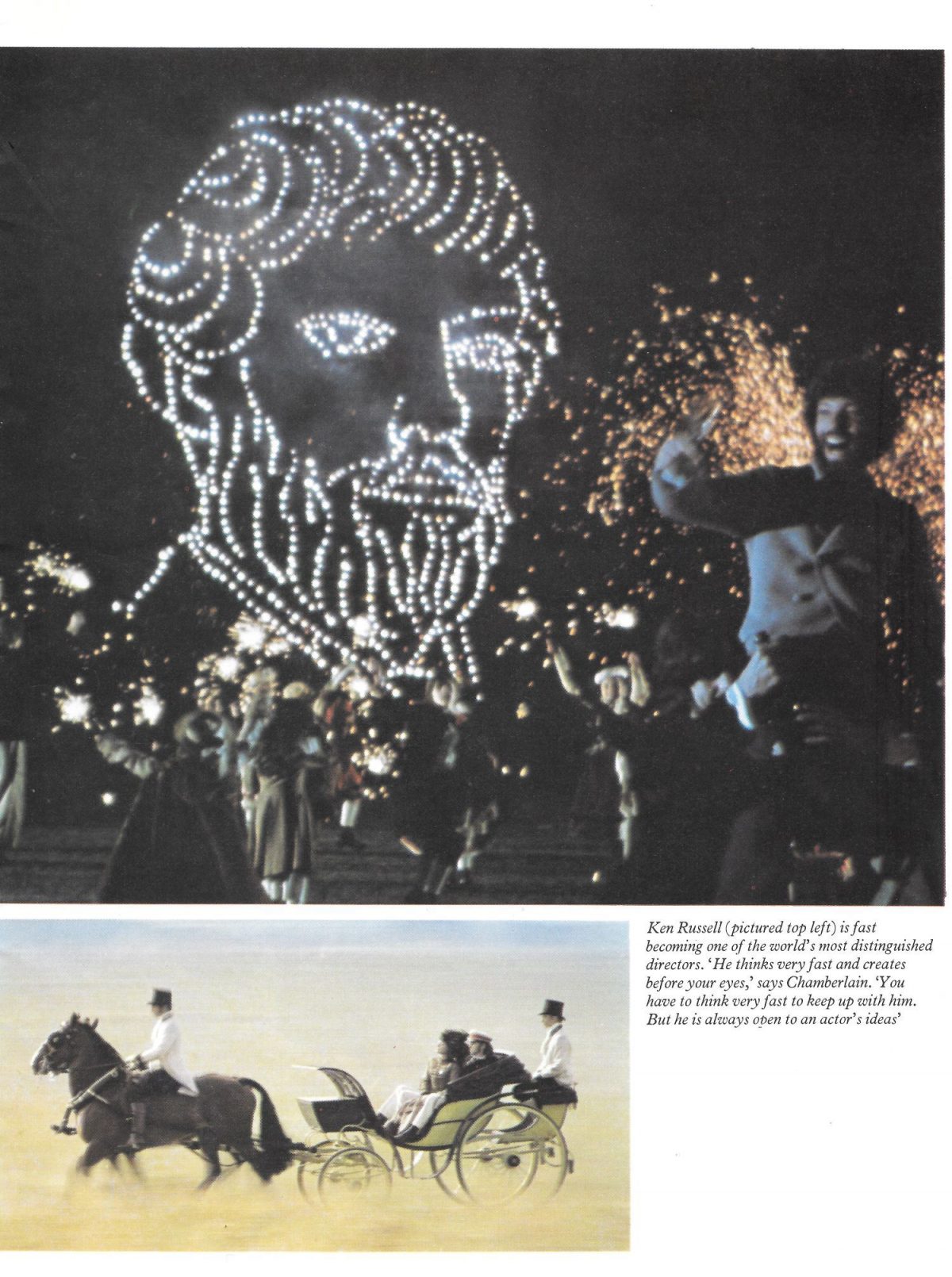

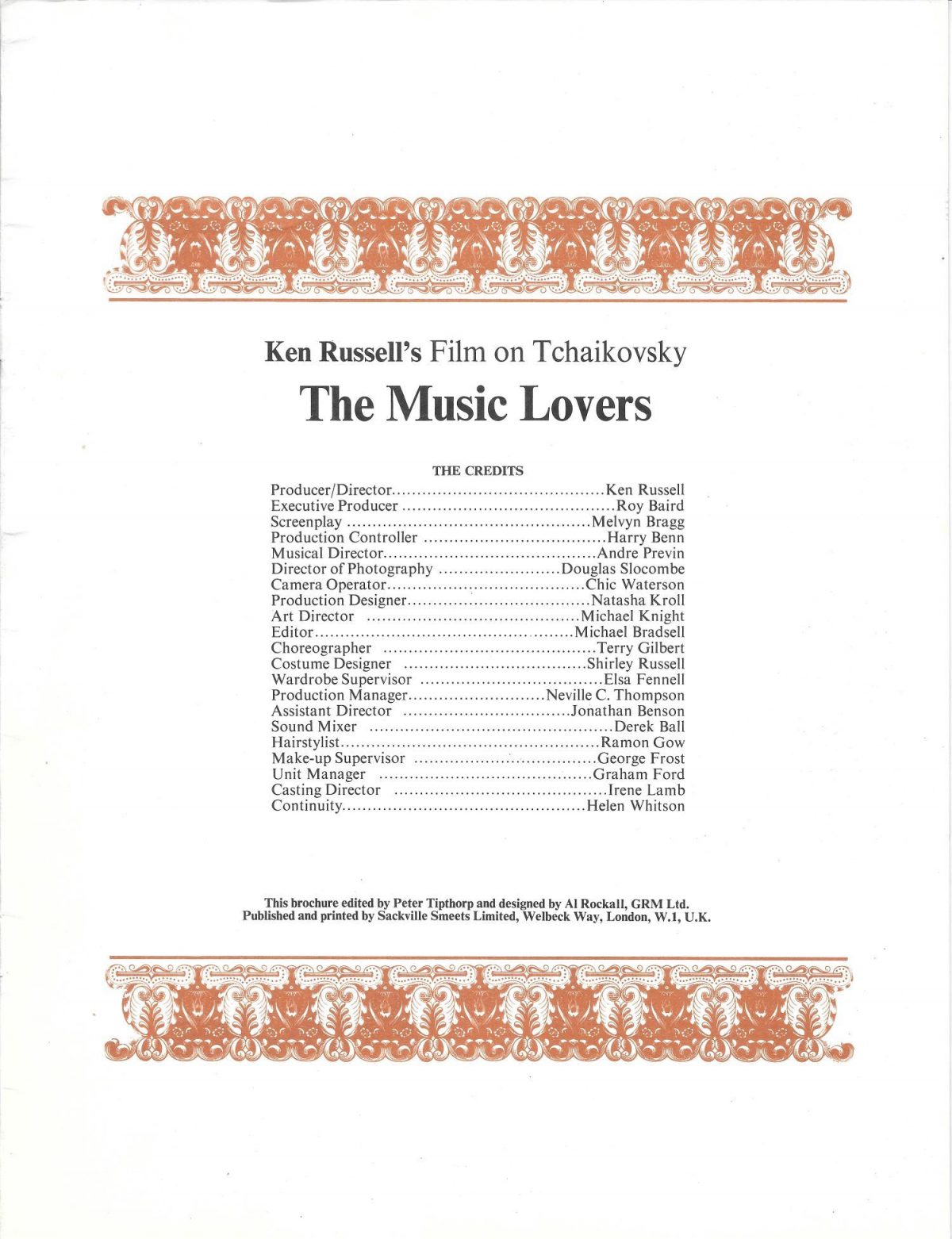

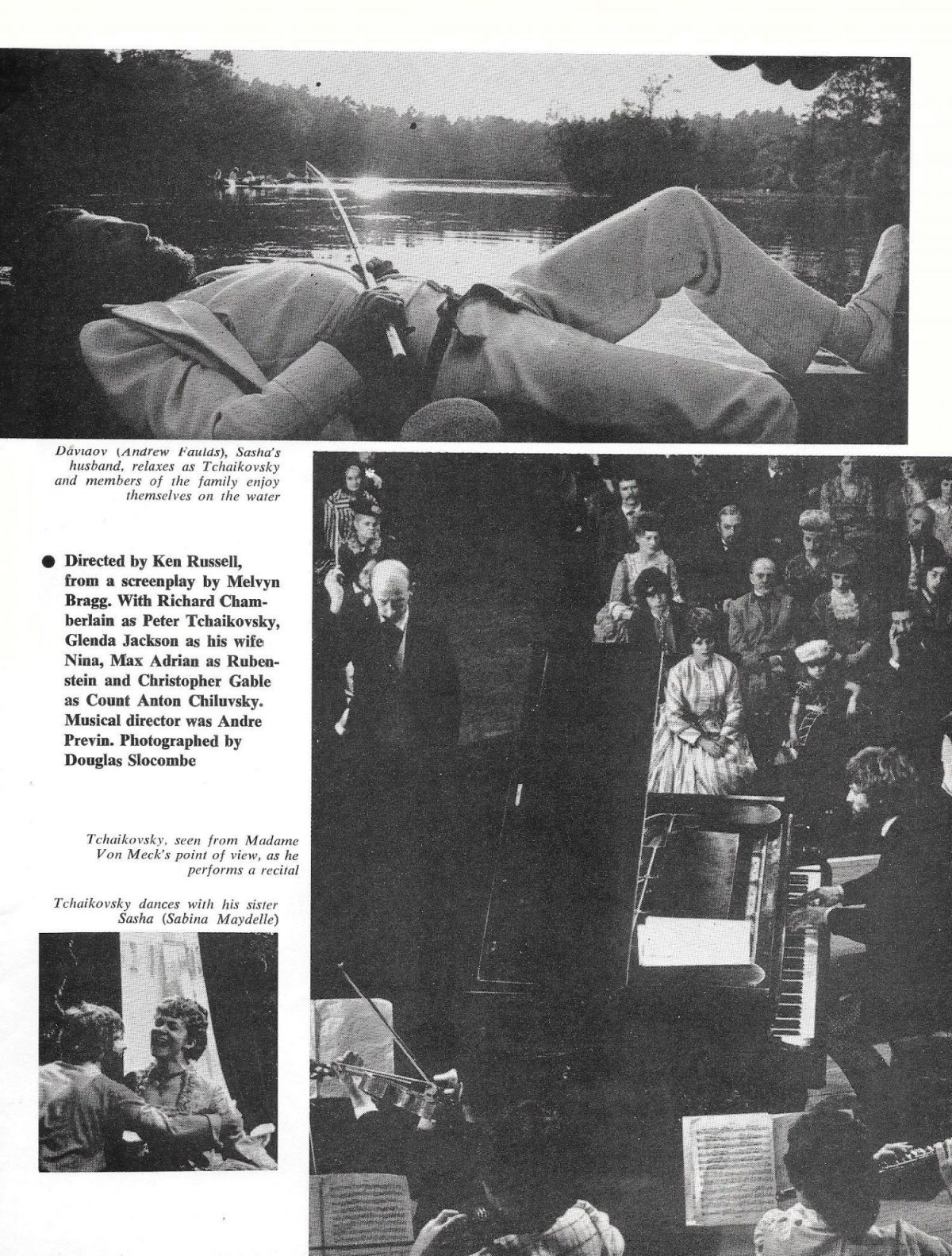

When Ken Russell pitched his biopic about Tchaikovsky, the production company United Artists were not too enthusiastic. Movie producers want box office moolah not arthouse applause. Russell pitched the film as “a story about a homosexual who fell in love with a nymphomaniac.” He hit the jackpot. UA stumped up a budget of $2million.

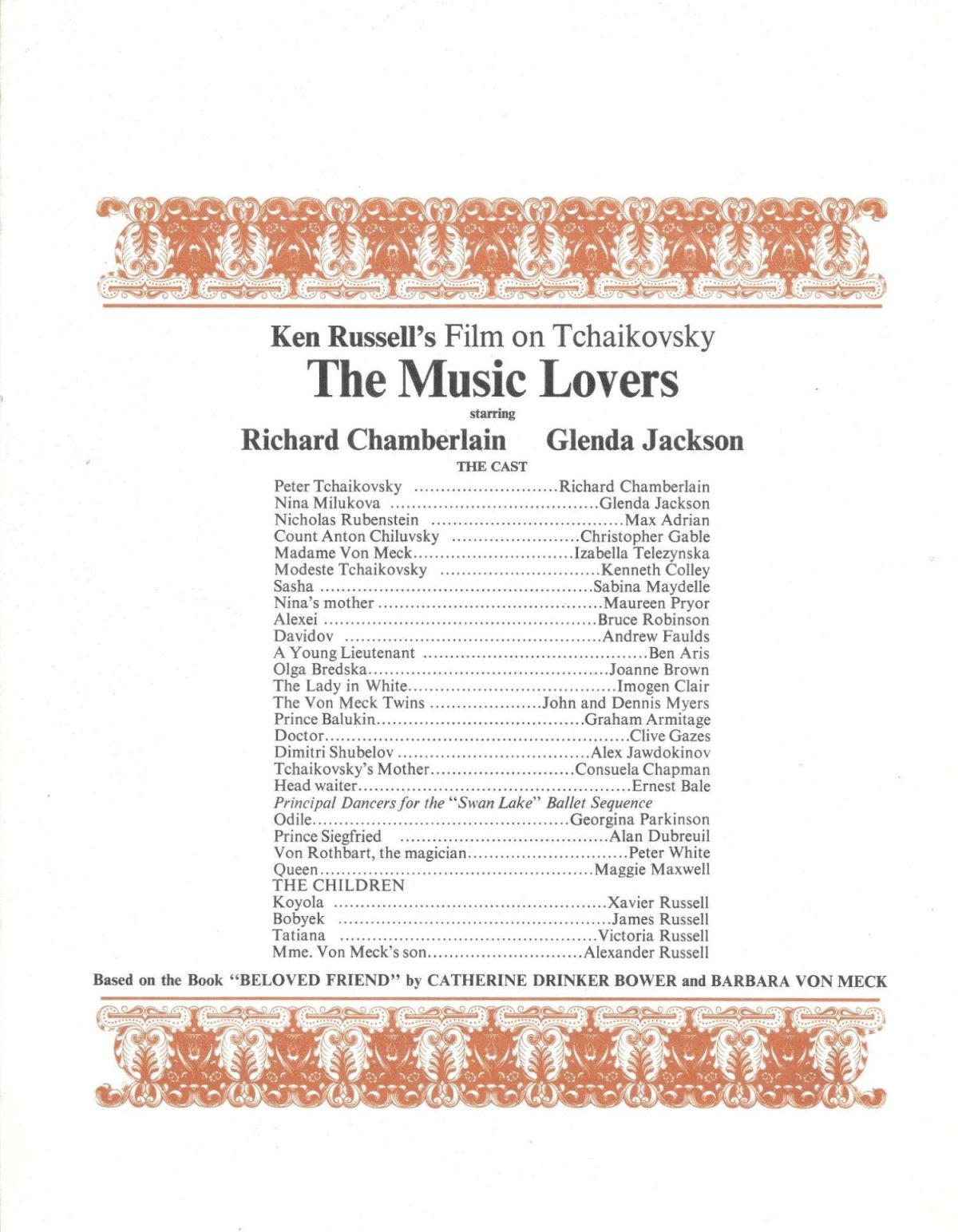

Cast

Russell wanted to cast Michael Caine as Gerald Crich in Women in Love. Caine had worked with Russell on The Billion Dollar Brain. He liked Russell’s suggestion but knocked it back because of the possible nude wrestling scene with Alan Bates. What would happen if he got a semi? Oliver Reed replaced Caine. Russell considered dropping the wrestling scene until Reed forced the director to film the scene as it was written in the book–which he kinda did.

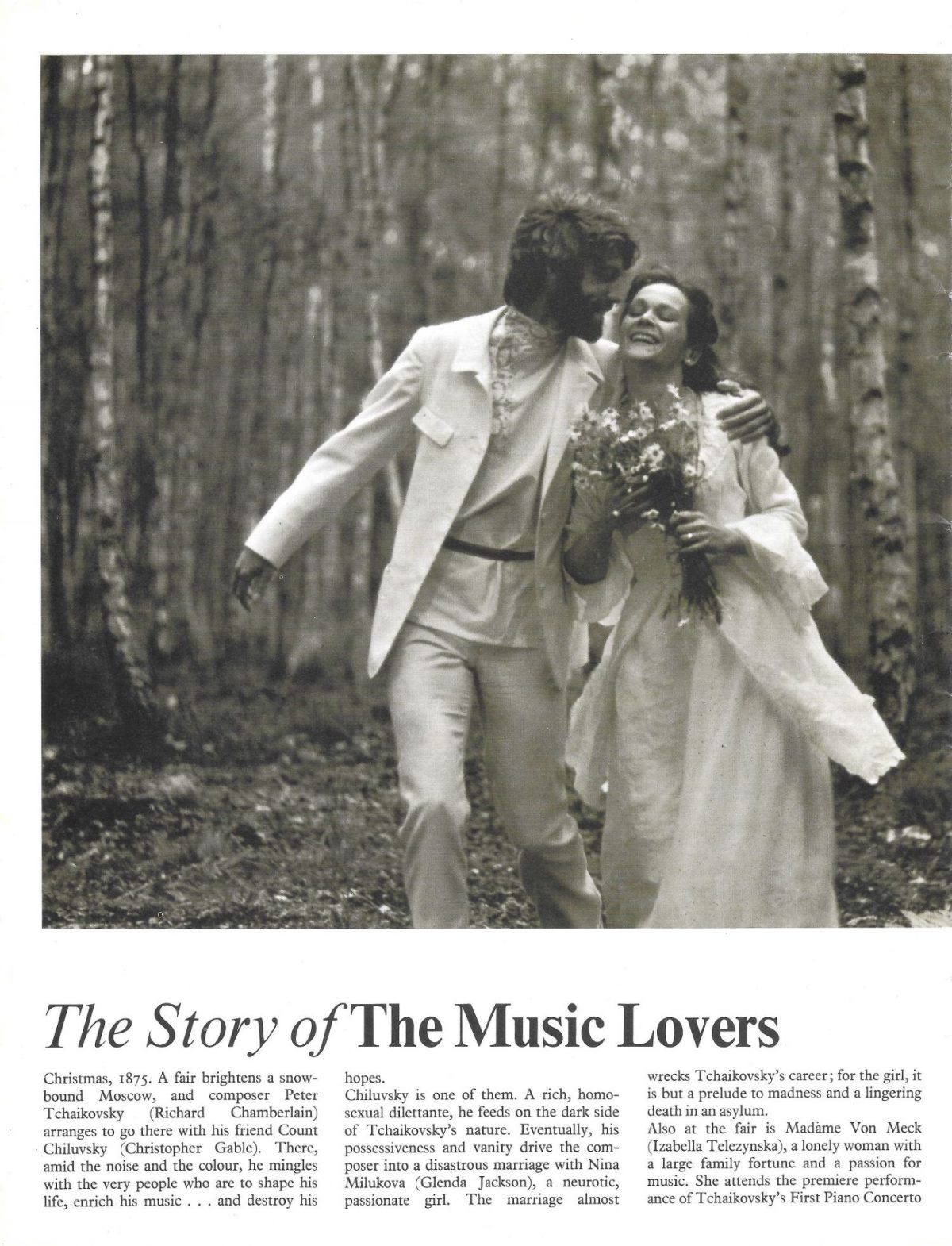

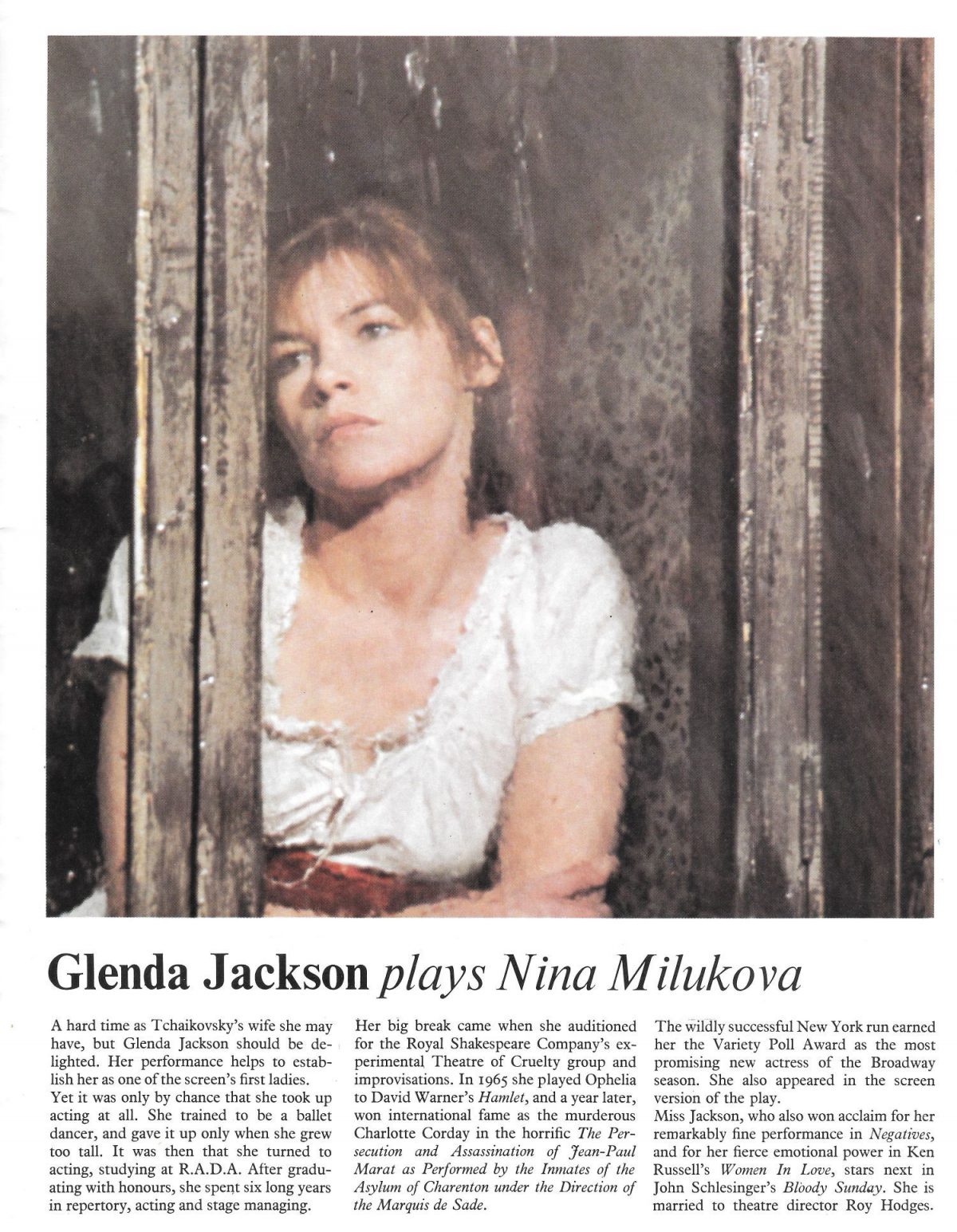

When it came to The Music Lovers, Russell wanted Glenda Jackson (then the greatest actress on the planet) to play Nina and Alan Bates to play Tchaikovsky. But Bates didn’t want to play another repressed homosexual or as Russell put it: Bates “thought it might not be good for his image to play two sexually deviant parts in rapid succession.”

One night while watching A Portrait of a Lady on the BBC, Russell saw his Tchaikovsky. It was Richard Chamberlain, an actor best-known as TV heart-throb Doctor Kildare. Russell would never have looked once at Chamberlain if he been sent the actor’s Kildare show reel. Chamberlain was considered eye-candy, pop TV, the housewife’s pin-up. But Chamberlain is an accomplished actor and his performance in Portrait of a Lady convinced Russell he had found his man. When the pair met, the deal was sealed when Chamberlain revealed he could “strum along” with Tchaikovsky’s music. Over the next few weeks, Chamberlain spent every free moment finessing his keyboard skills. This meant Russell could film Chamberlain playing the piano. If you’ve seen the film, you’ll know how good/convincing is Chamberlain’s performance.

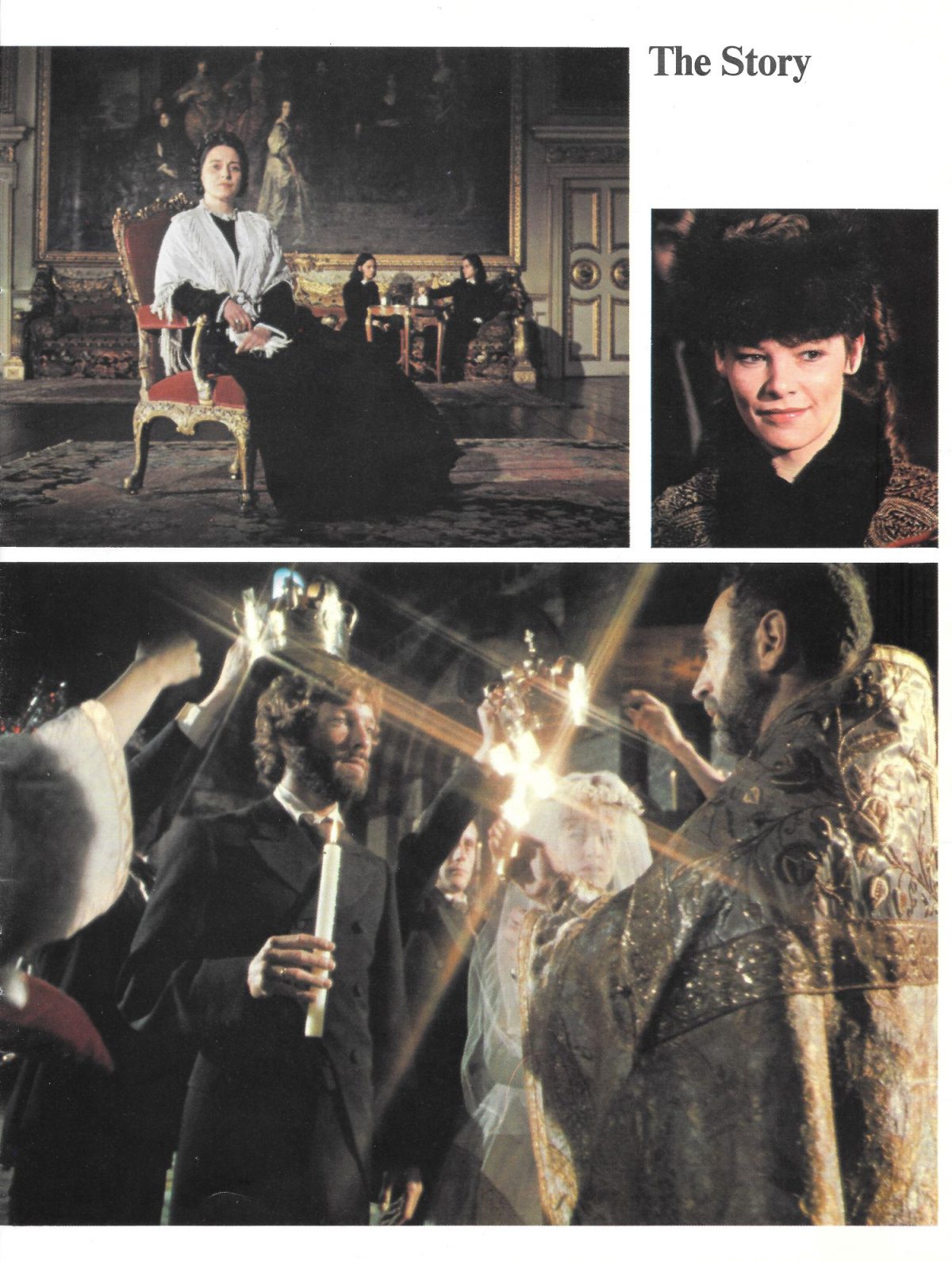

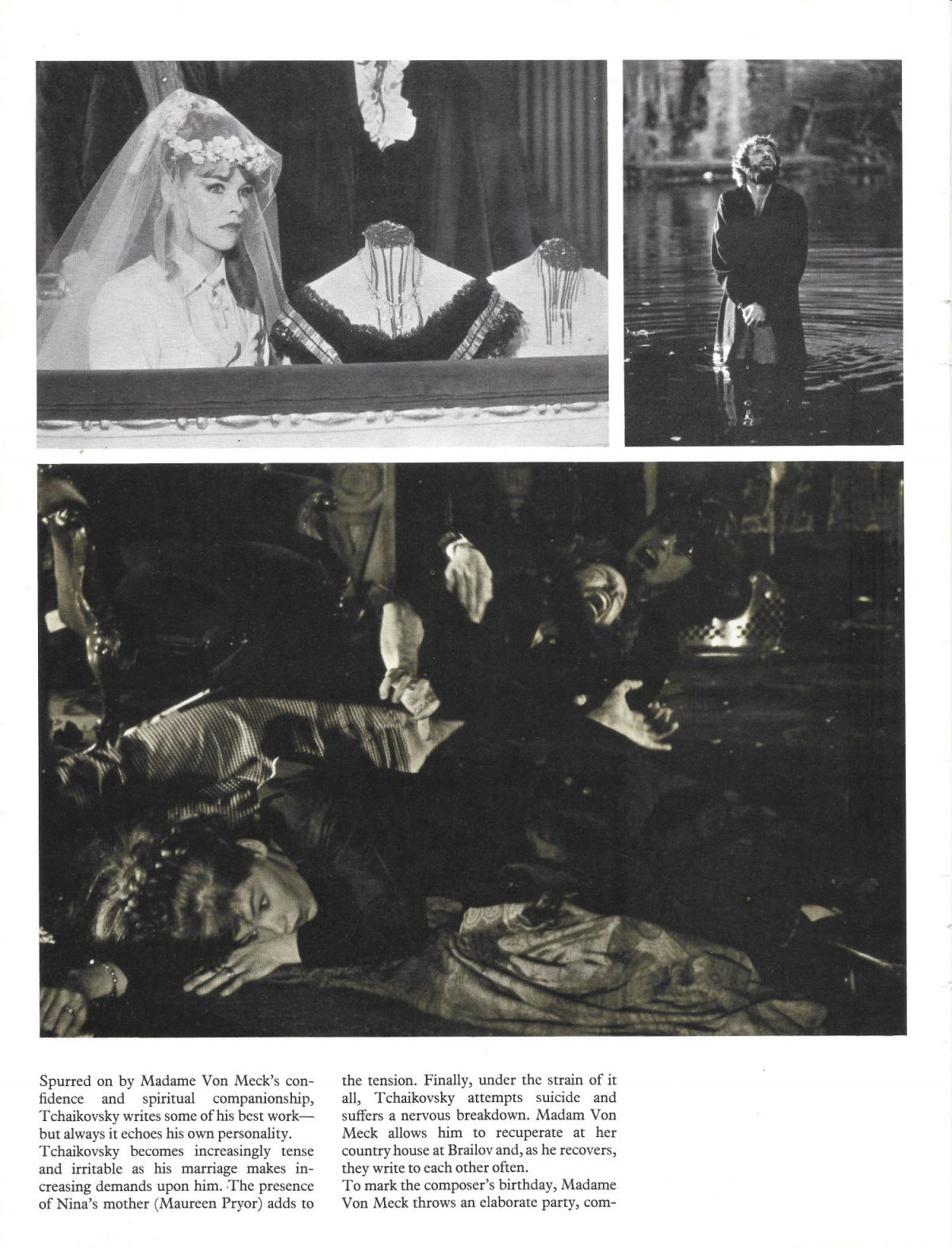

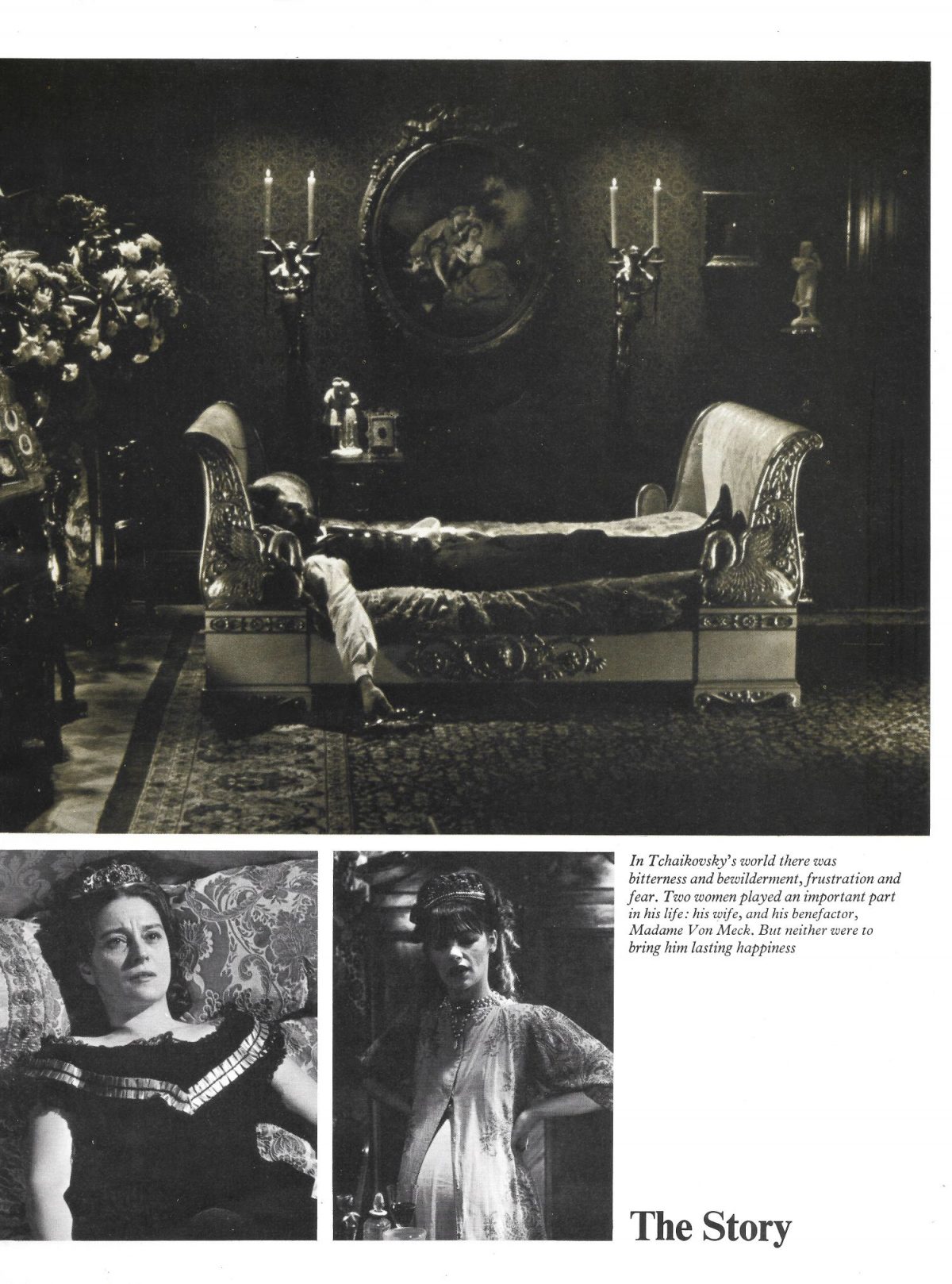

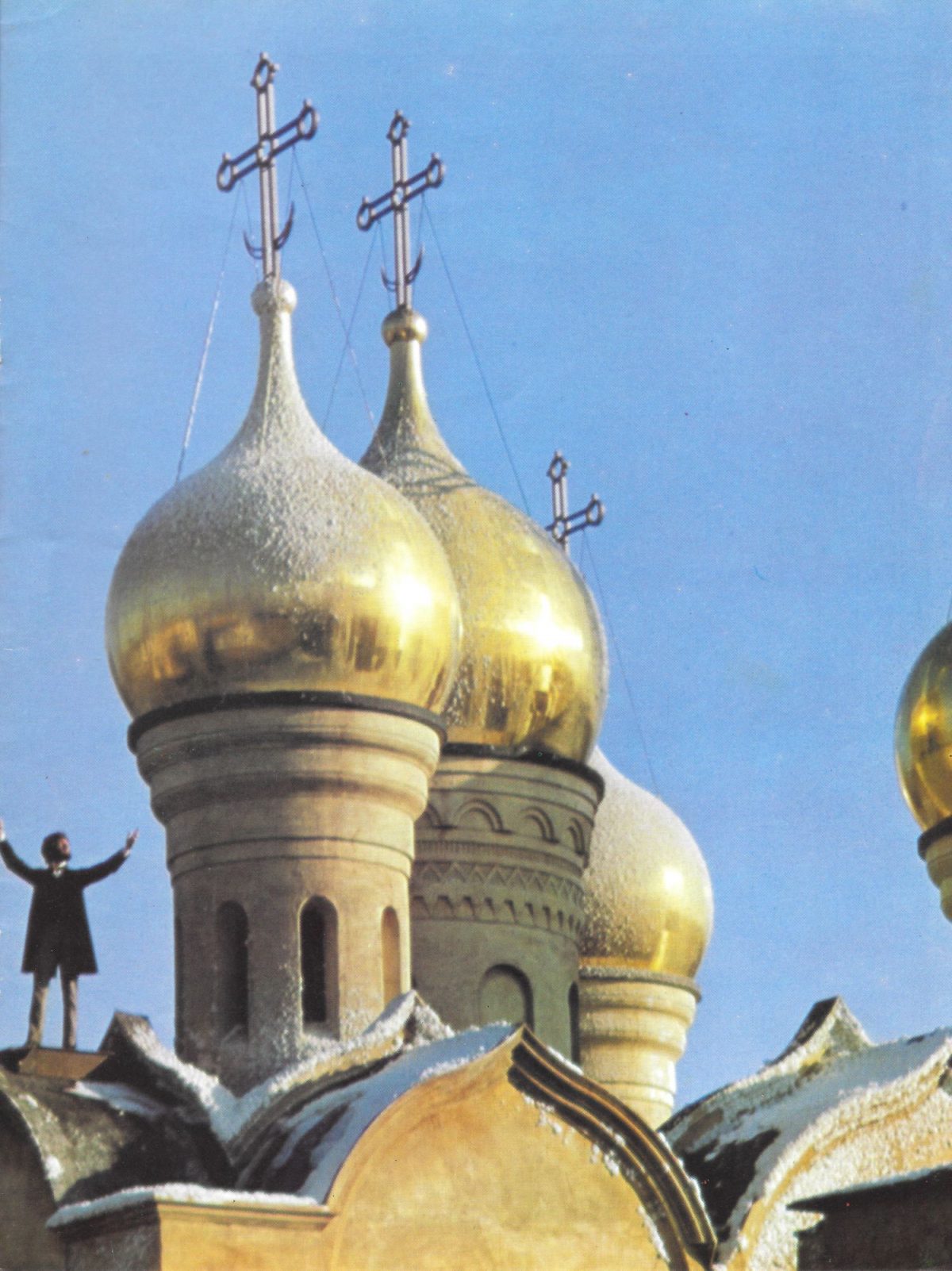

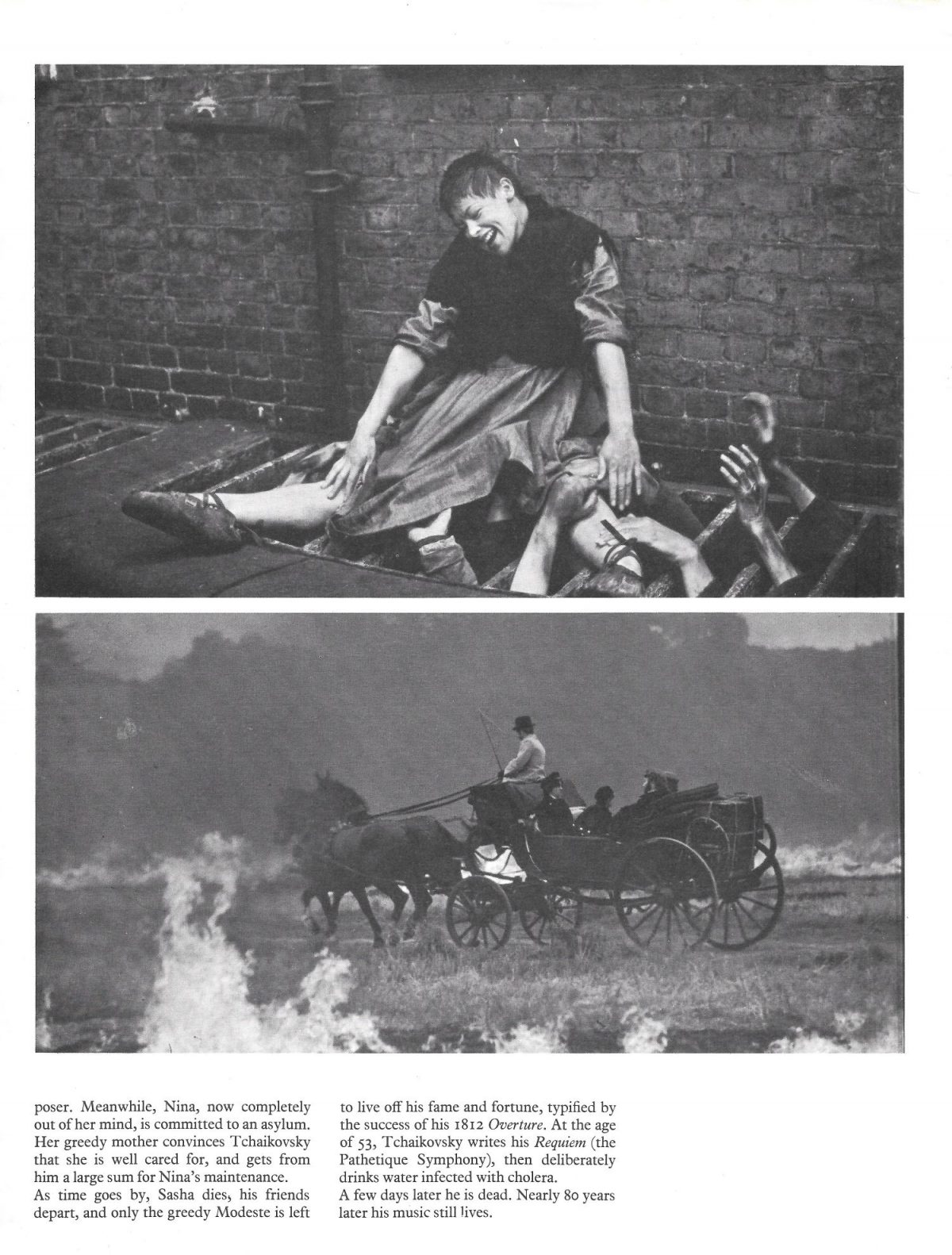

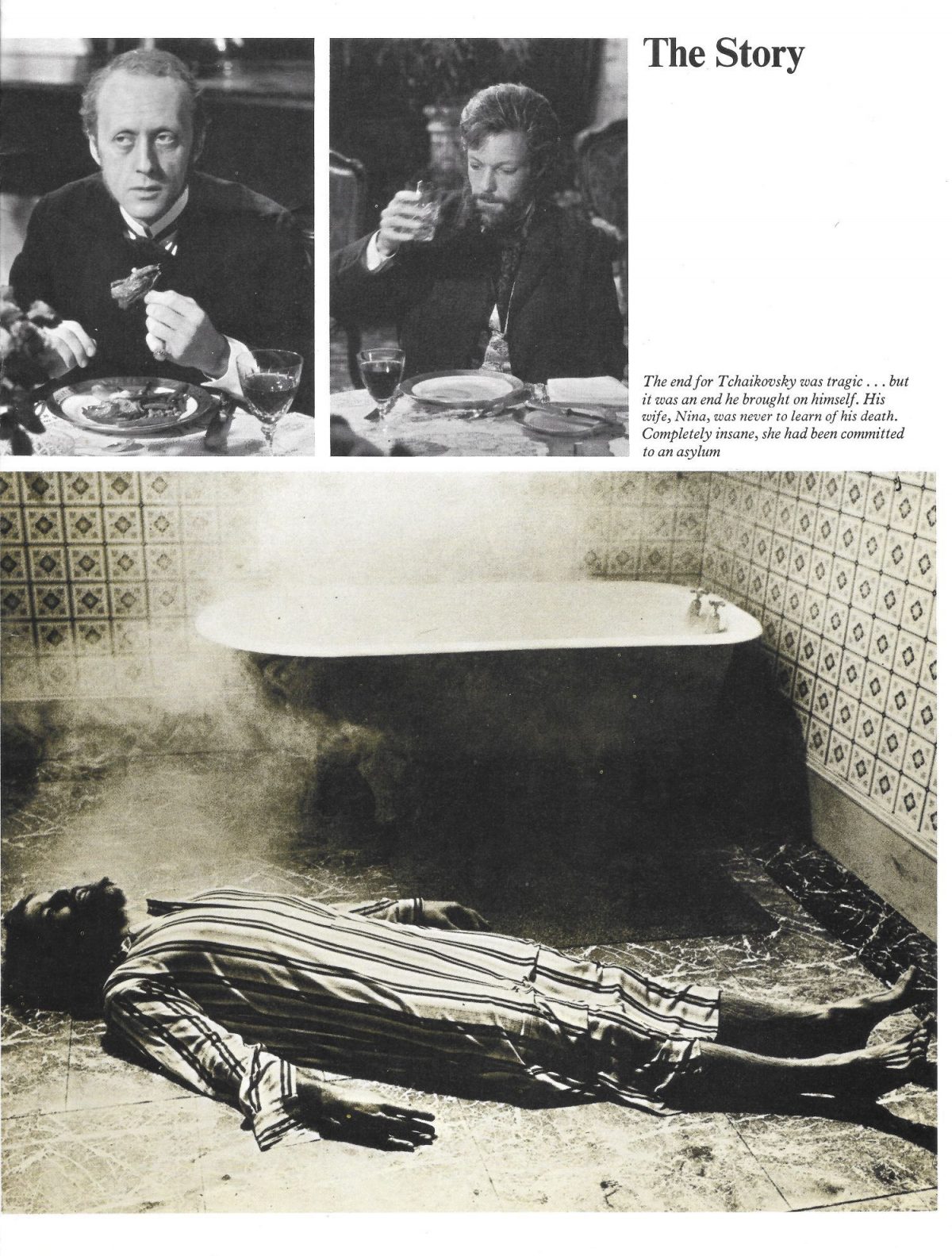

The Story

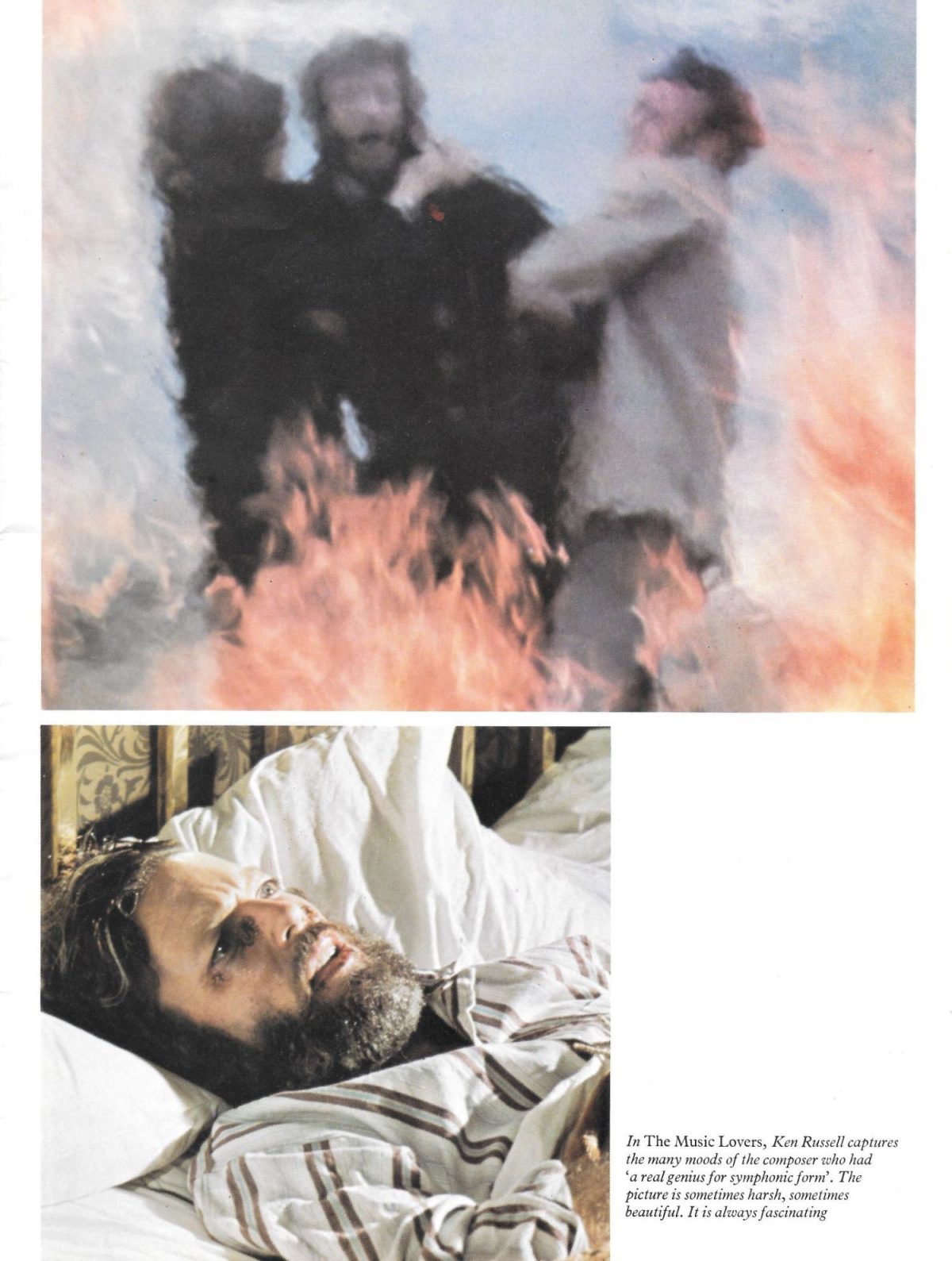

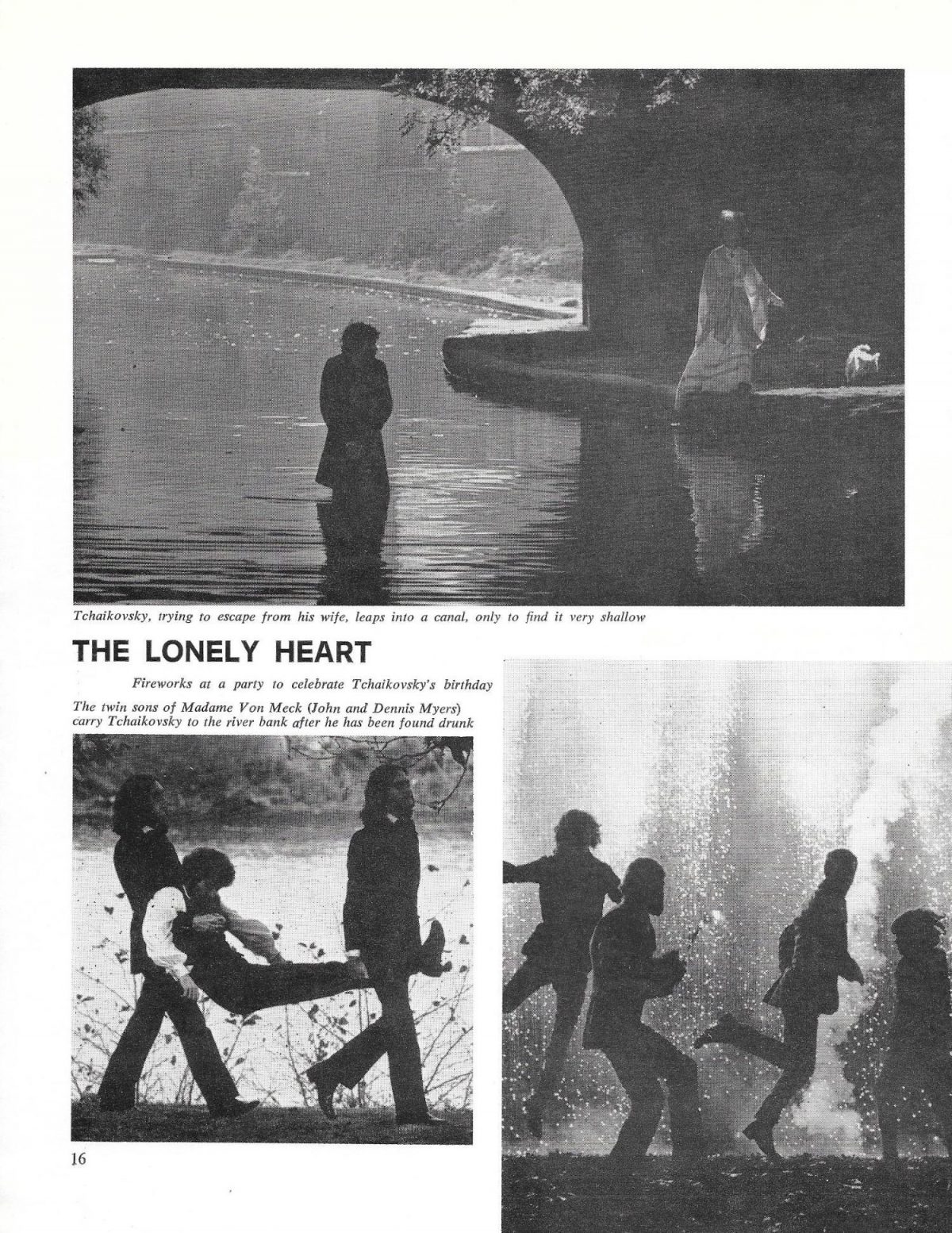

Ken Russell‘s movies cannot be judged or even viewed like normal mainstream movies. His films are, as Colin Wilson once wrote, like Beethoven’s symphonies: they must be judged on their own merit. This especially applies to The Music Lovers, where Russell created a complex, ironic, multi-layered narrative, that demands the full attention of the audience. O, yeah, ye can watch the film and enjoy it for its story, its energy, and its undeniable passion–but, The Music Lovers is a film that gives more with repeated viewings. Trust me. Small things lost on a first viewing suddenly form a pattern which reveals the director’s intent.

Russell co-wrote the screenplay with Melvyn Bragg. Their intention was not a biopic but a film which viewed Tchaikovsky through the people in his life. Hence the title Ken Russell’s Film on Tchaikovsky and The Music Lovers. The script was based on Beloved Friend, a collection of letters edited by Catherine Drinker Bowen and Barbara von Meck. A book Russell-biographer Joseph Gomez described as “slightly suspect”. That was part of Russell/Bragg’s intention: to use a book which can supply the dialogue but also present an image created by a biographer. We’re dealing with interpretation rather than the truth but where interpretation is far more truthful.

When released, The Music Lovers received the worst reviews of Russell’s career. Yet it was major box-office hit in Europe and is now considered (by some) to be one of, if not the best Russell biographical movie.

American critics made the mistake of thinking the Oscar-nominated director was making a Hollywood biopic. These critics judged the film through their own prejudices rather than using their intellect. Quelle surprise… Hence such insane comments by American critics like Russell and his film should have a stake driven through his/its heart. Or (Roger Ebert) calling the film “totally irresponsible” or Variety comparing the film to the blood thirsty French theatre of Grand Guignol.

Ah, critics–their work is always about them and their private fears rather than the subject matter at hand.

But it matters not as movies out live the chip wrappers of yesterday.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.