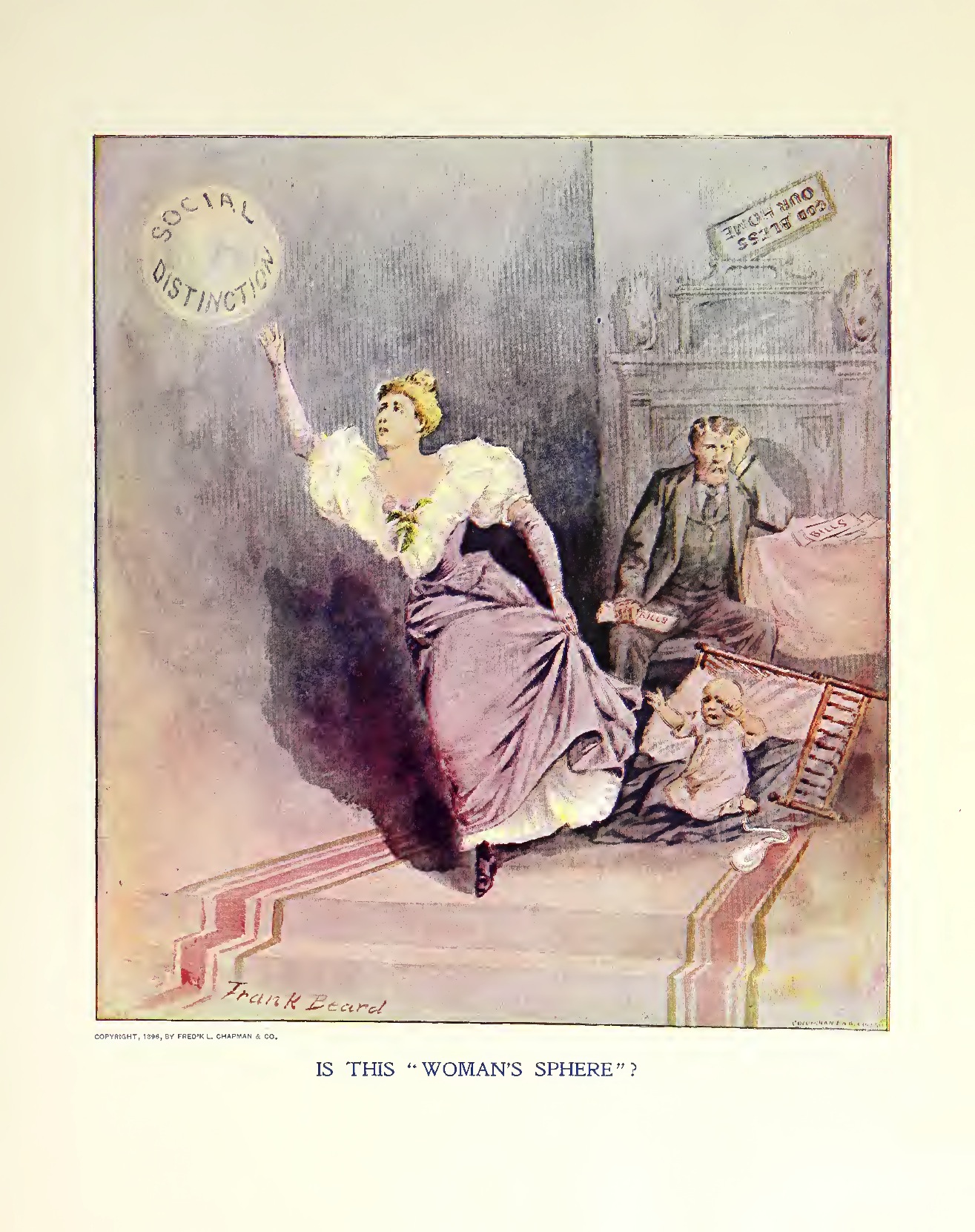

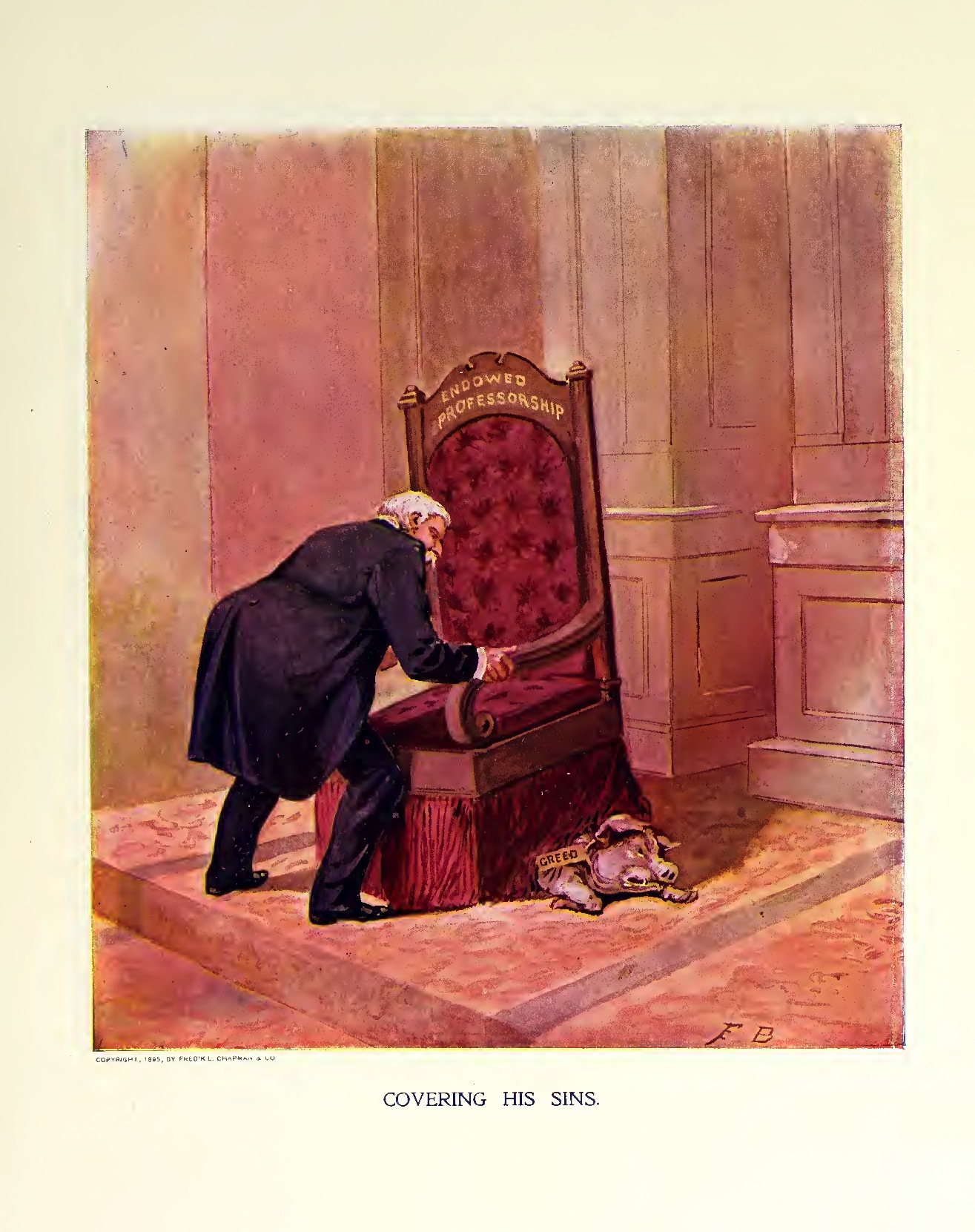

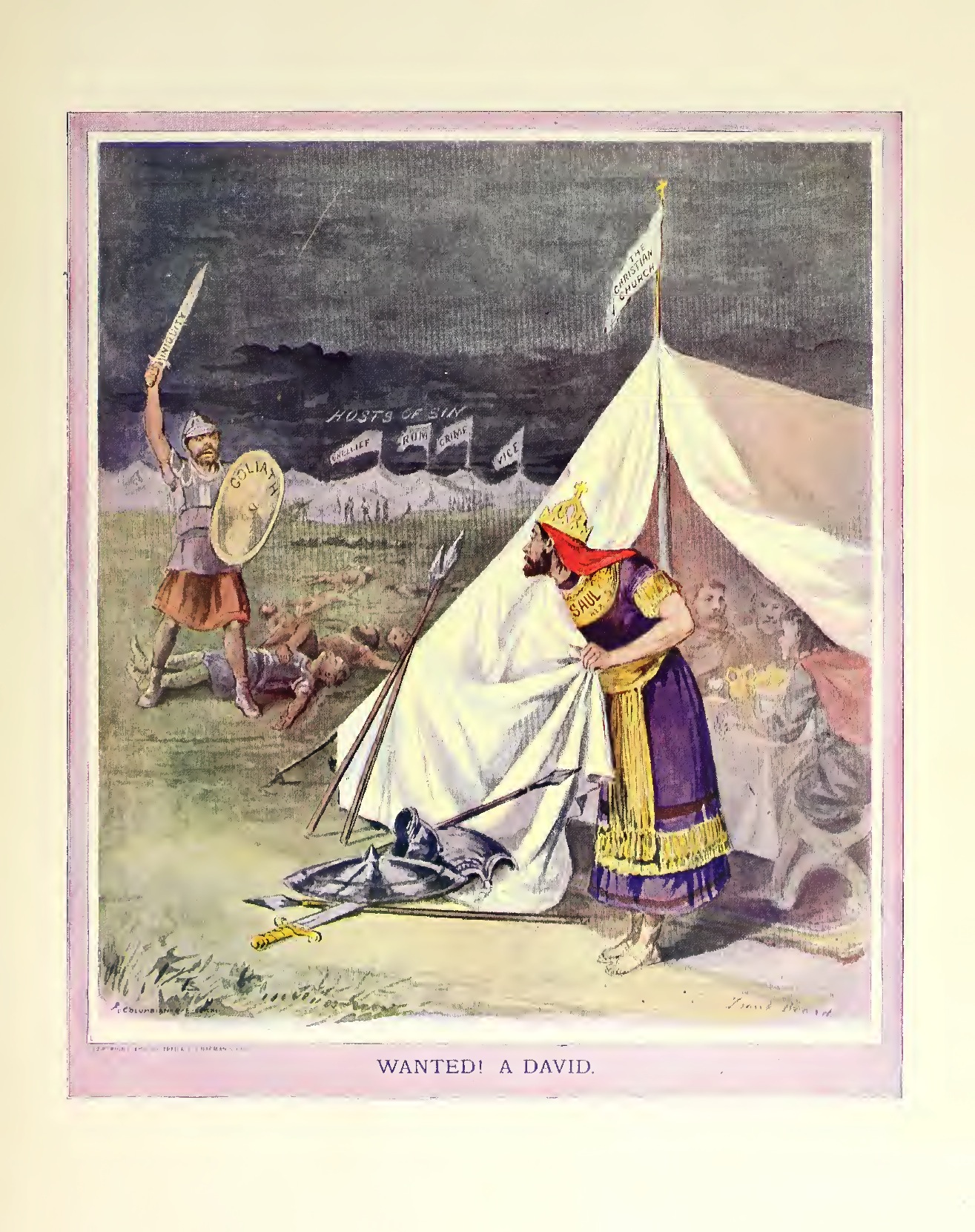

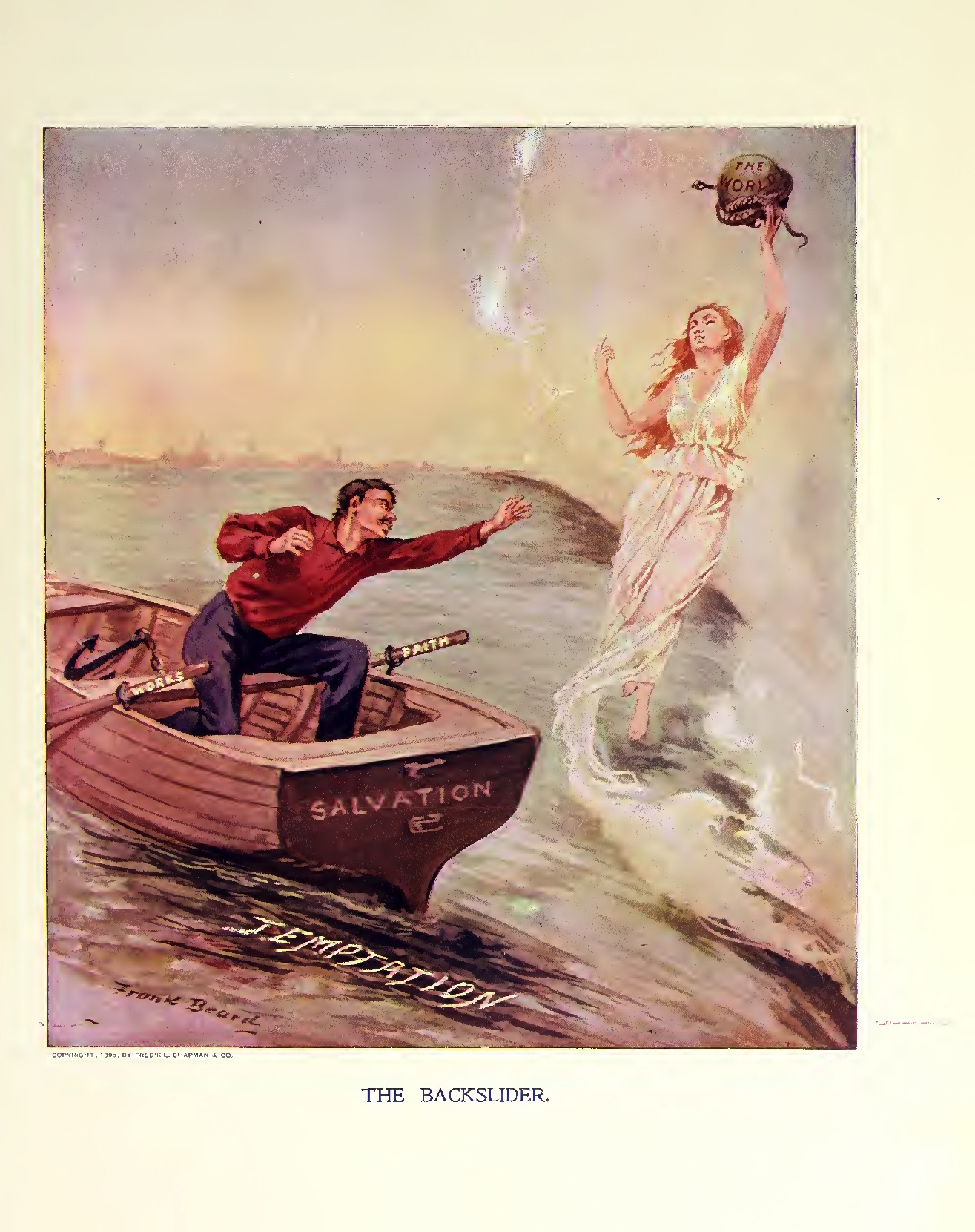

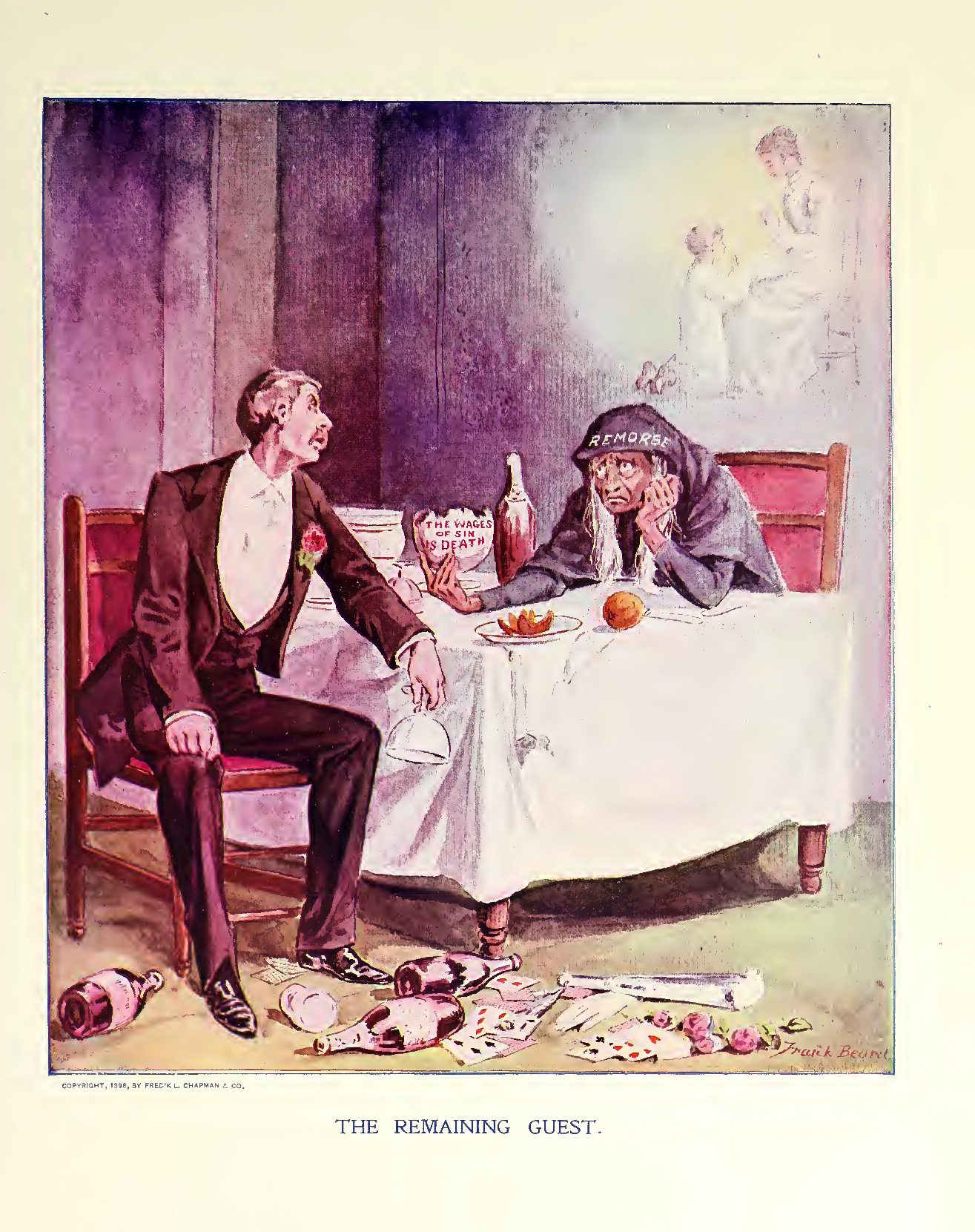

The Ram’s Horn, “an interdenominational social gospel magazine”, was published in Chicago, Illinois, during the 1890s and the early years of the twentieth century by Frederick L. Chapman & Company. Frank Beard (1842-1905) was the editor and principal illustrator of the organ that advocated abstinence and salvation through Christ. (The Anti-Saloon League, formed in Beard’s native Ohio in 1893, featured his work in many of their anti-booze pamphlets.) Most of the images that follow are his illustrations scanned from Fifty Great Cartoons (Chicago: The Ram’s Horn Press, 1899).

The Ram’s Horn’s editors observed that “the religious forces of America” had an “immense auxiliary…in the religious press”. It aimed to be the publication of choice for god-fearing Americans who, according to a survey it published in February 1896, bought a lot of religious publications:

143 denominations in the U.S. had 111,000 ministers and 1,138 newspapers, mostly weekly in their publications. The number of copies of each issue totaled 4,216,242. The Ram’s Horn in 1893 had a circulation of 4,200, a circulation that in 1896 had grown to 52,000.

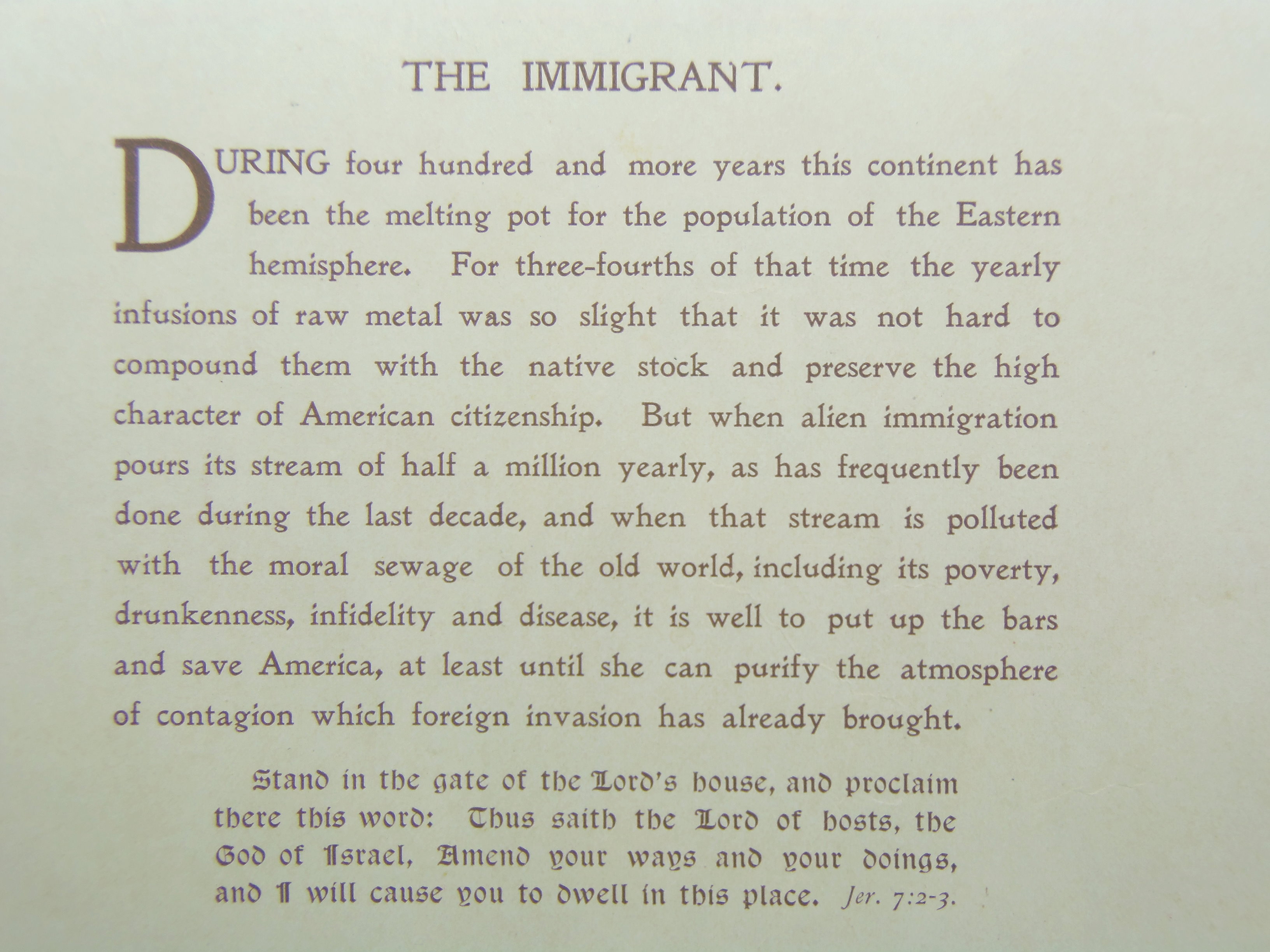

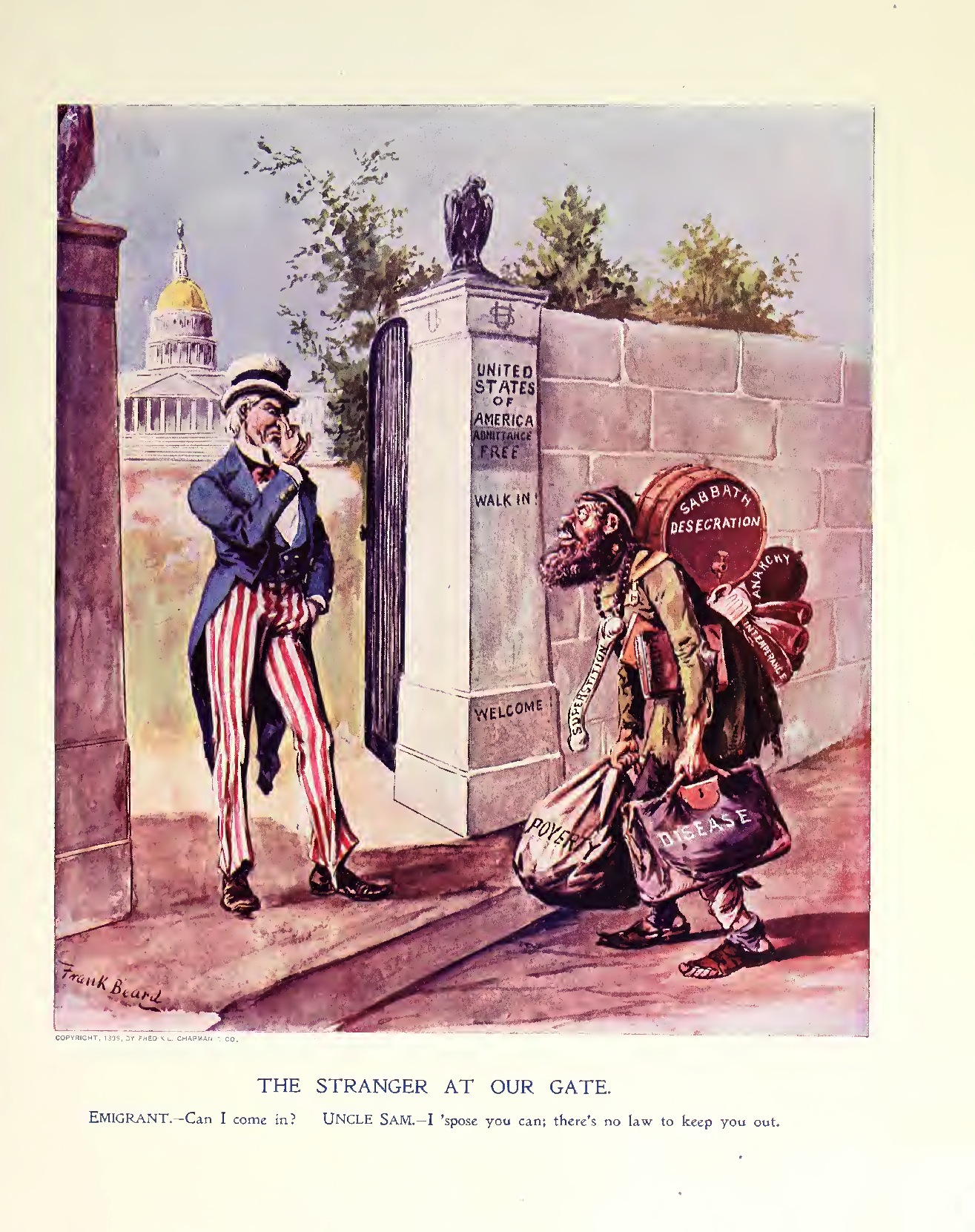

Beard saw many ills afflicting American society, with immigrants copping no little flack.

Apparently, the author of the text for The Stranger at Our Gate (April 25, 1896) did not see the irony of using a quote by a Jewish prophet to justify discriminating against Jewish immigrants and their “moral sewage”:

THE STRANGER AT OUR GATE.

EMIGRANT.–Can I come in?

UNCLE SAM.–I ‘spose you can; there’s no law to keep you out.

DURING four hundred and more years this continent has been the melting pot for the population of the Eastern hemisphere. For three-fourths of that time the yearly infusions of raw metal was so slight that it was not hard to compound them with the native stock and preserve the high character of American citizenship. But when alien immigration pours its stream of half a million yearly, as has been frequently done during the last decade, and when that stream is polluted with the moral sewage of the old world, including its poverty, drunkenness, infidelity and disease, it is well to put up the bars and save America, at least until she can purify the atmosphere of contagion which foreign invasion has already brought.

Stand in the gate of the Lord’s house, and proclaim there this word: Thus saith the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, Amend your ways and your doings, and I will cause you to dwell in this place.

Jer. 7:2-3.

“There is no reason why the devil should have all of the best tunes,’ and it is equally hard to conceive why he should have all of the best pictures.”

– Methodist leader Charles Wesley quoted in the intro to Fifty Great Cartoons.

“The social gospel typically advocated abolition–taking away the licenses–of the businesses that made, distributed, and sold alcoholic beverages, prohibition. The “father of the social gospel,” Washington Gladden, for instance, helped found the Anti-Saloon League that successfully engineered enactment of the prohibition amendment in 1919.”

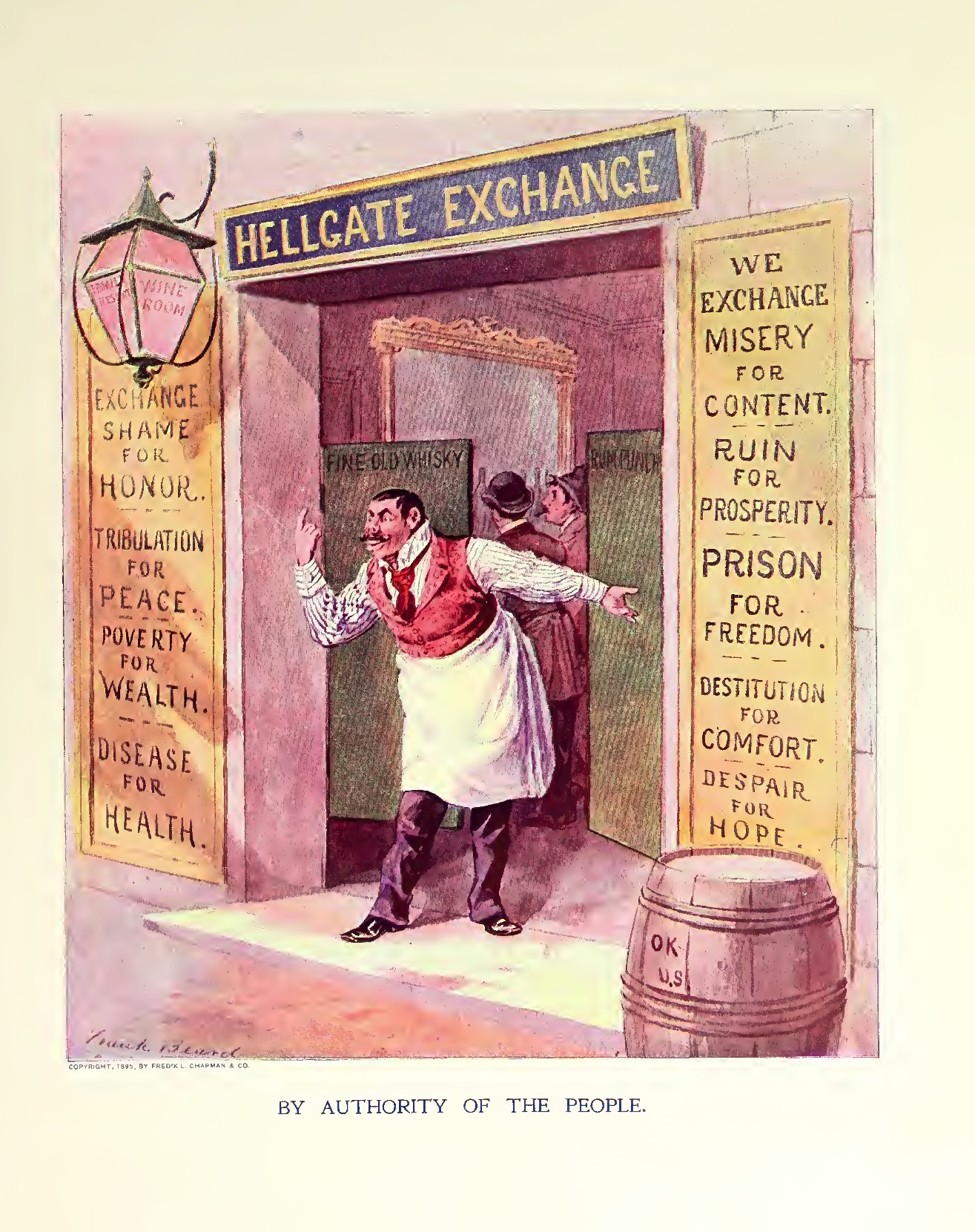

When the famous submarine reef known as Hell Gate was blown out of the waters of Long Island Sound, the world echoed with rejoicing to learn that what had been a menace and a barrier to vessels and to commerce was blasted into fragments never to return. There is a greater Hell Gate which with its infinite submarine and subterranean tunnels honeycombs our social structure. The saloon is the dreadful barrier to commerce and prosperity, as well as a menace to health and peace. In spite of the fact that its awful traffic bears the approving stamp of our government, the time will come when this great thing, whose foundations are laid in hell, will be blown skyward by the power of public sentiment mightily aroused and intellectually directed.

Woe unto him that giveth his neighbor drink, that putteth thy bottle to him, and makest him drunken also.

Hab. 2:4

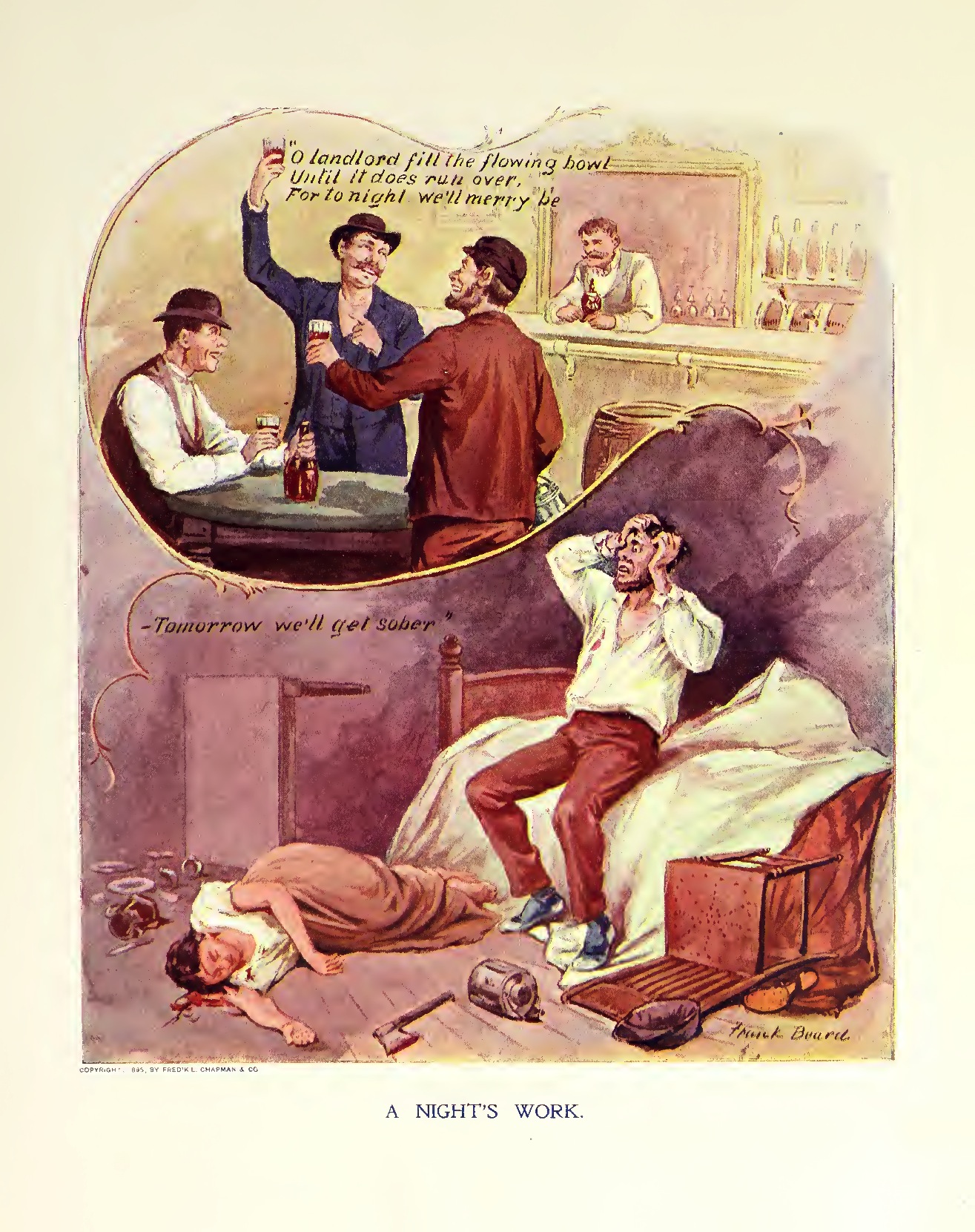

A Night’s Work

More than one man has been handed for doing what he did not mean to do. When anyone under the influence of liquor commits a crime it is no longer an extenuation or defense to say that he was not responsible. This is so because it is a matter of human experience that if one sets a match to gunpowder it will explode and if one pours liquor down his throat he is filing his brain with the seeds of malice, hate and murder. Many a man has scoffed at such a statement at twelve o’clock at night, but has seen awful proof of its truth, when, awakening at nine in the morning he recovers from a fatal debauch and sees the work of his own drunken and murderous hand.

At the last it biteth like a serpent and stingeth like an adder.

Prov. 23:32

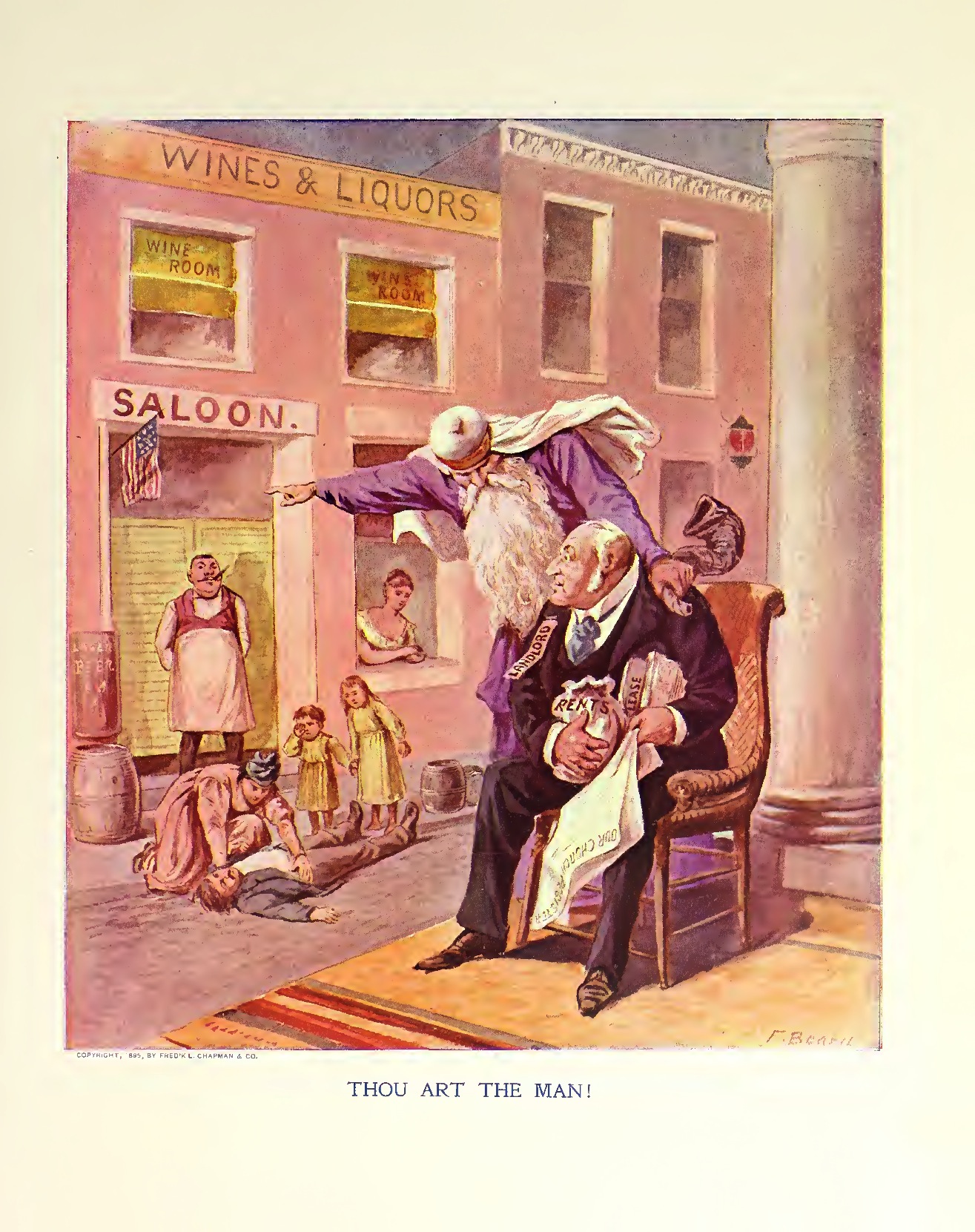

THOU ART THE MAN!

Law and justice hold an accessory to a crime liable to punishment as strictly as they hold the principal. Indeed oftentimes it is the wily accessory who is the more guilty, because from his cowardly place of retreat he directs the plot which may result in physical peril to the one who carries it through. Is not likewise the man who rents his property the evil uses equally if not more guilty than the one who boldly assumes the responsibility of carrying on an indecent traffic therein. There would be a thinning of the ranks of respectability if public sentiment should face every Dives who is a silent partner in the tenements of sin and say, Thou art the man whom we hold guilty and responsible for this murder and this poverty and this vice.

When thou sawest a thief, then thou consentedst with him, and hast been partakers with adulterers.

Psalm 50:18

RESCUED.

WHEREVER the tide of human life flows very deeply and swiftly, there shipwreck is most frequent and we place Rescue Missions at these points. But do we ever think of there being rescue missions in the skies? Could we scan the far battlements of heaven we might, perhaps, see them lined with hosts of angels watching and waiting to descend to the rescue of some tender child whom it were better to snatch away to scenes of glory, than leave it in an atmosphere that reeks with moral contagion. It wa such a scene as appears on the page opposite that Isaiah saw when he wrote “He shall gather the lambs with his arm and shall carry them in his bosom.”

He shall save the children of the needy, and shalll break in pieces the oppressor.

Psalm 72:4.

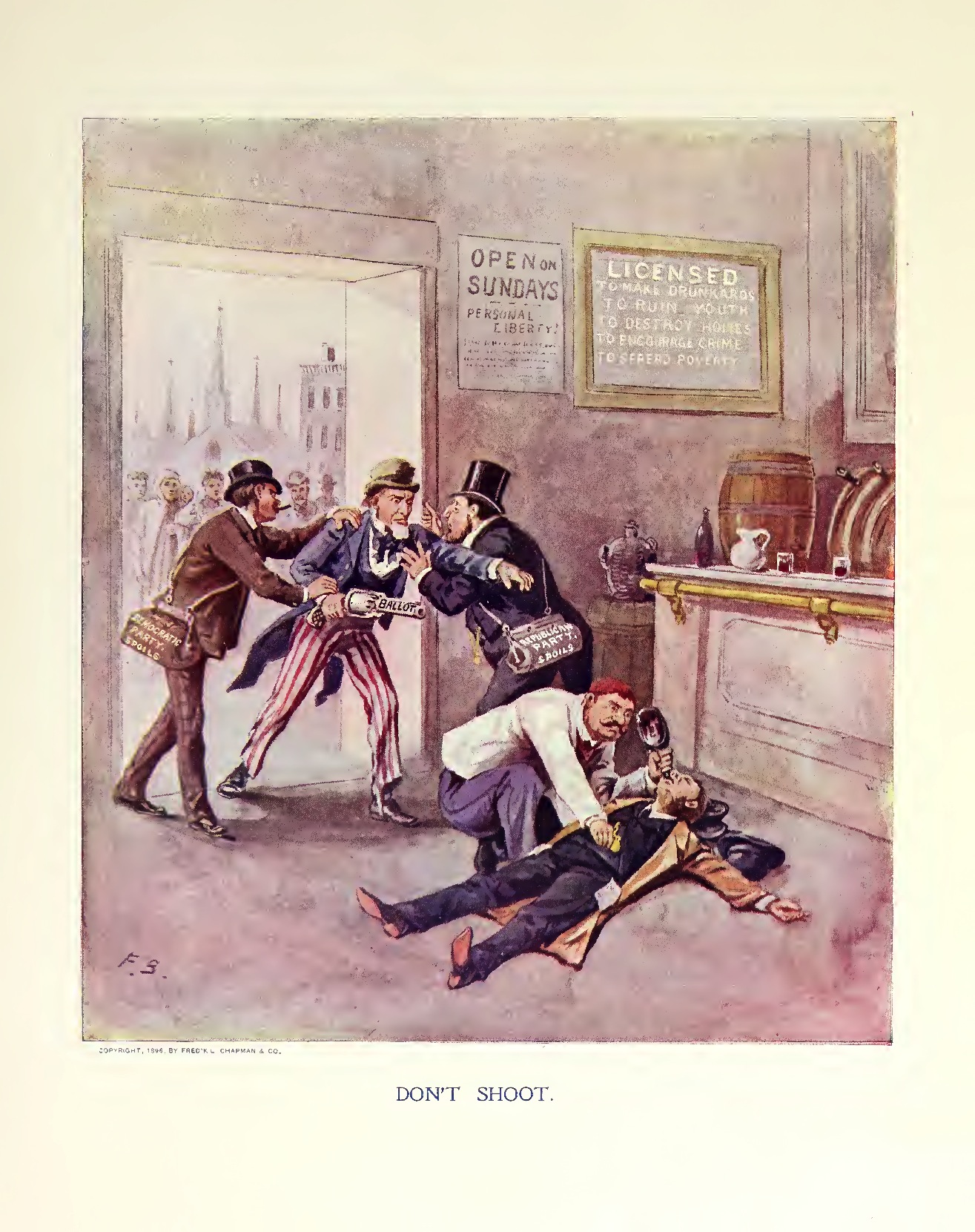

DON’T SHOOT.

IT would be easy to destroy the liquor traffic were it not for its power in politics. This is so apparent to the men who manage it that they make it their first business to engage in politics and lay candidates for office under obligations by making generous contributions to the campaigns of each party. Therefore, whenever a cry of robbery or murder goes up from the licensed saloon and the government grabs bayonet and ballot and runs to the rescue, the political managers immediately step forth and intervene. Don’t Shoot, they both cry; Let him rob and ruin. He is a friend of mine and he has a license.

And he said unto them; Hinder me not, seeing the Lord hath prospered my way.

Gen. 24:56.

UNDER THE CLOAK OF THE LAW.

CONCERNING the work of the saloon there is but one verdict which can be rendered by intelligence and patriotism. Ten thousand times ten thousand times it has been brought before the bar of Justice and there charged and proved with being responsible for the vast majority of poverty, crime and disease which infest the race. Nevertheless, so deeply is this blighting curse intrenched in our laws and government that our courts are compelled, even if unwilling, to protect a traffic which by common agreement is a universal bane. Knowing this, the saloonist seeks refuge under the cloak of the law, and there insolently defies us to assail him.

He that justifieth the wicked, and he that condemnth the just, even they both are abomination to the Lord.

Prov. 17:14.

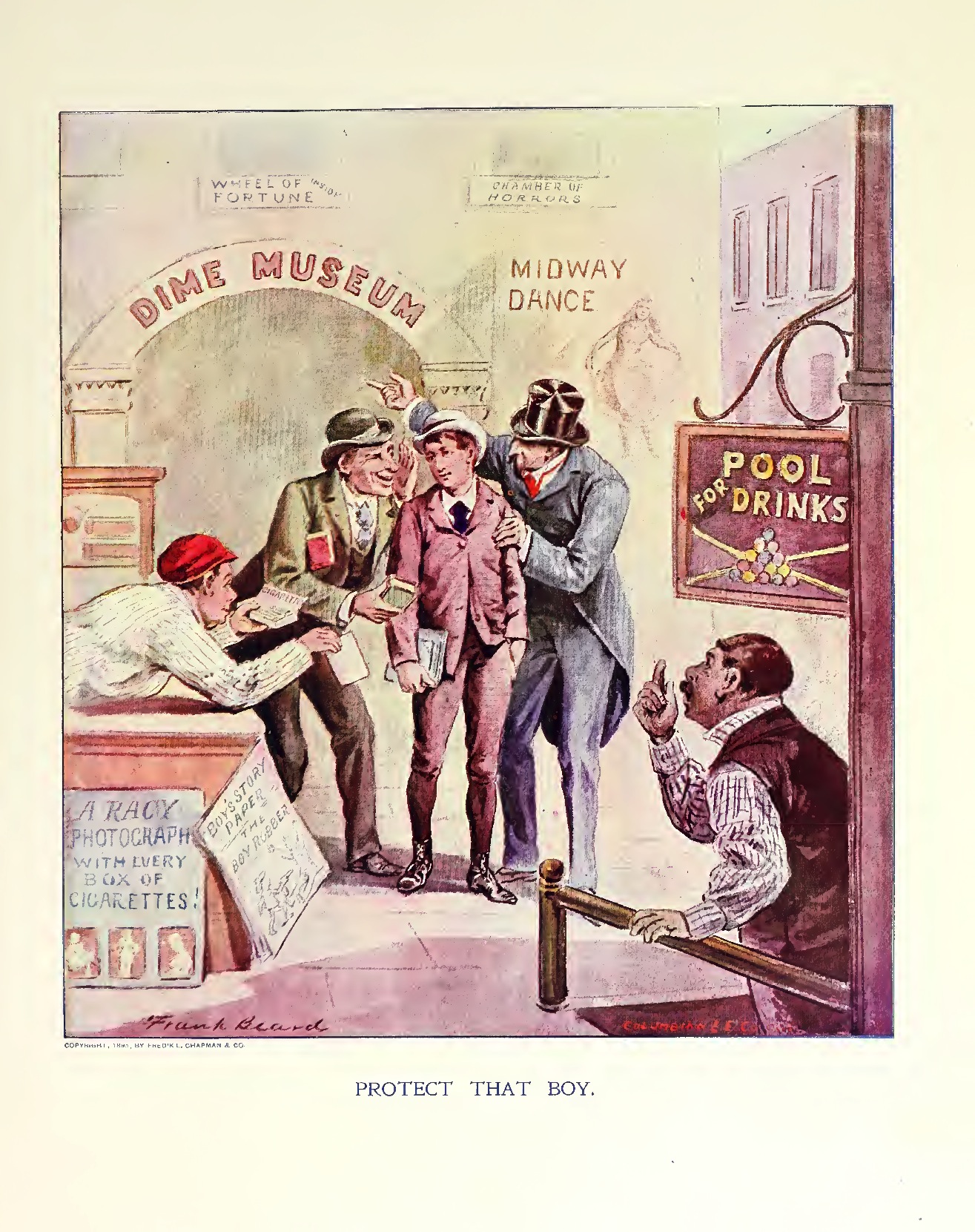

PROTECT THAT BOY.

THE controllers of the liquor traffic understand their business. They know that they are sending an army of drunkards each year to an untimely grave and to take the place of these fallen victims, they must gain recruits from the hosts of youth. But the Rum haunts are too hideous to beguile one of tender years. There must be less offensive sins offered to bridge that long leap from innocence to iniquity, from the home hearth to the dram shop. Therefore, the rumseller goes in league with the seller of cigarettes, and base literature, and evil pictures, and questionable games and entertainments. At last the youthful victims of these plotters find themselves on the threshhold of ruin. Every avenue through crime and vice leads at last to the open saloon.

The days of his youth hast thou shortened: thou hast covered him with shame.

Psalms 89:45.

FRANK BEARD TALKS

On September 15, 1895, Frank G. Carpenter interviewed Frank Beard for the Morning Oregonian.

CHICAGO, Sept. 11.– I have just had a talk with Frank Beard about himself and American caricature. He is, to a certain extent, the father of the American cartoon, and he has been making funny pictures for the newspapers all his life. He is now about 50 years of age, and his first picture was published when he was under 30. He has opened a new field in cartooning, as the editor of the Ram’s Horn. This is the Puck and Judge of Chicago, but its pictures are semi-religious instead of political. In it Frank Beard is trying to reform the religious world by exposing its shams. The paper had nothing of a circulation when he took hold of it. It now publishes 50,000 a month, and is rapidly becoming one of the leading pictorials of the country. Its field was well expressed by Mr. Beard during the talk, when I asked him as to what he thought of the future of American caricature. He replied:

“I think we are just at the beginning of the use of the cartoon. Pictures can often tell stories quicker and better than words, and I believe that cartoons can be used in the service of religion, righteousness, truth and justice without being subject to pary. I believe in the fundamental principles of Christianity, but I can take a text from the Bible, and with the utmost reverence can, through the medium of the cartoon, apply it to the civilization of today. I can point a moral in this way, and by a picture can make a tract which every man who sees it must read. This is what we are trying to do through the Ram’s Horn, and we are succeeding beyond my expectations.

THE FIRST CHALK TALK.

My talk with Frank Beard took place in his office, and before I go further I want to tell you how it was carried on. Frank Beard is as deaf as a post, and he has been so from birth. The only way to talk with him is through a black rubber tube, about as big around as a garden hose and as long as your arm. This he always has about his neck. When you talk to him he uncoils it and puts one end of it to his ear and hands you the other. You place your lips to the mouth of the tube, and through this make your connection with Frank Beard’s brain. Mr. Beard is an inveterate sketcher, and during my conversation he illustrated his points by drawing pictures, talking all the while, so that it seemed a race between his tongue and his pencil as to which should convey the idea first. There is no man in the United States who can give forth ideas in this manner as he can. He is, you know, the originator of the chalk talk, and there is hardly a town in the United States in which he has not given this sort of a lecture. Standing on the platform with a roll of paper stretched on an easel before him, and with a half-dozen colored crayons in his hand, he carries his audiences away with him while he draws pictures illustrating the philosophy, fun and satire which he throws at them in solid chunks. There are today a score or more of this kind of entertainers in the United States. Frank Beard, however, was the author of the business, and he made today a sketch for me in illustration of his story as to how he came to make the first chalk talk. Said he:

“It is now more than twenty years since I gave my first talk of this kind. I was a young artist of New York, and had just gotten married. My wife was an enthusiastic church-goer and a great deal of our courtship was carried on in going to and from the Methodist church. The result was that I struck a revival and became converted. This occurred shortly after I was married, and like other enthusiastic young Christians, I wanted to do all I could for the church. I was on hand at all the meetings, and I took part in all the church work. Now, our church, like many others in the United States, was very hard up. We were always needing money for something, and we tried to supply this by means of entertainments and socials. Soon after I joined the church the young people gave an exhibition, and the ladies suggested that I draw some pictures as a part of it. I consented, but I felt that the standing-up before an audience and sketching without saying anything in illustration of the pictures would be a very silly thing. So I concluded to make a short talk and draw the sketches in illustration of it. I wrote out my story and rehearsed it half a dozen times beforehand. The entertainment was for a Thanksgiving celebration, and one rehearsal took place at home, my wife, my mother-in-law and the turkey, which we tied up in a chair, forming the audience. Well, my wife survived, my mother-in-law did not die while I was talking, and the turkey was not spoiled. The exhibition came off in the church, and it was a great success. Other churches heard of it, and I had applications to repeat it again and again. At first I was flattered and readily consented. I never thought of charging for it until the demands became so numerous that I was unable to fill them. It was taking much of my energy and lots of my time. To put a stop to it my wife suggested that I charge so much for each entertainment. So, when the next application came, I replied that I could oblige them, but that it would cost $30. To my surprise they accepted my offer by return mail. It was so with nearly everyone who wrote, and I soon found that I was making more at my chalk talks than at my newspaper work. I then charged $40, then $50, and so on, until I now get what is considered a very good price. I don’t like to lecture very well, however. The wear and tear is too great, and you have to hurry too much to make trains.”

A BOY SKETCHER.

“When did you make your first cartoon, Mr. Beard?” I asked.

“My inclination to make caricatures dates back to my boyhood, “ was the reply, “My father was an artist, you know, and he has painted some very good pictures. When I was a boy, away back in the ‘30s, we lived in Plainville, Ohio, a little town near Cleveland. The chief county paper at this time was the Yankee Notions. It would be considered a very poor thing today, but it was the best of its kind then. As soon as I saw it, I became one of its regular subscribers. All of my spare cents went for it. When I was about 10 years old, I came in to my mother one day with this paper in my hand and said: “Ma, I am going to draw some pictures and send them to the Yankee Notions.”

“’All right my son,’ was the reply, ‘If you think you can do so.’

“I then asked her to give me the jokes, that I might make pictures to them. She objected to this, and told me that I must make the jokes, as well as the pictures. And that the man who made the one always made the other. This bothered me somewhat, but I finally succeeded in making a joke and a picture. I mailed it to the paper, and in due time received 50 cents for it. This seemed a great deal of money to me, and for a long time after that I thought of nothing but jokes and pictures. I kept sending more jokes, and sometimes, I remember, I got as much as $5 at a time for 10 jokes. This was a fortune for a schoolboy, and I was the envy of my companions.”

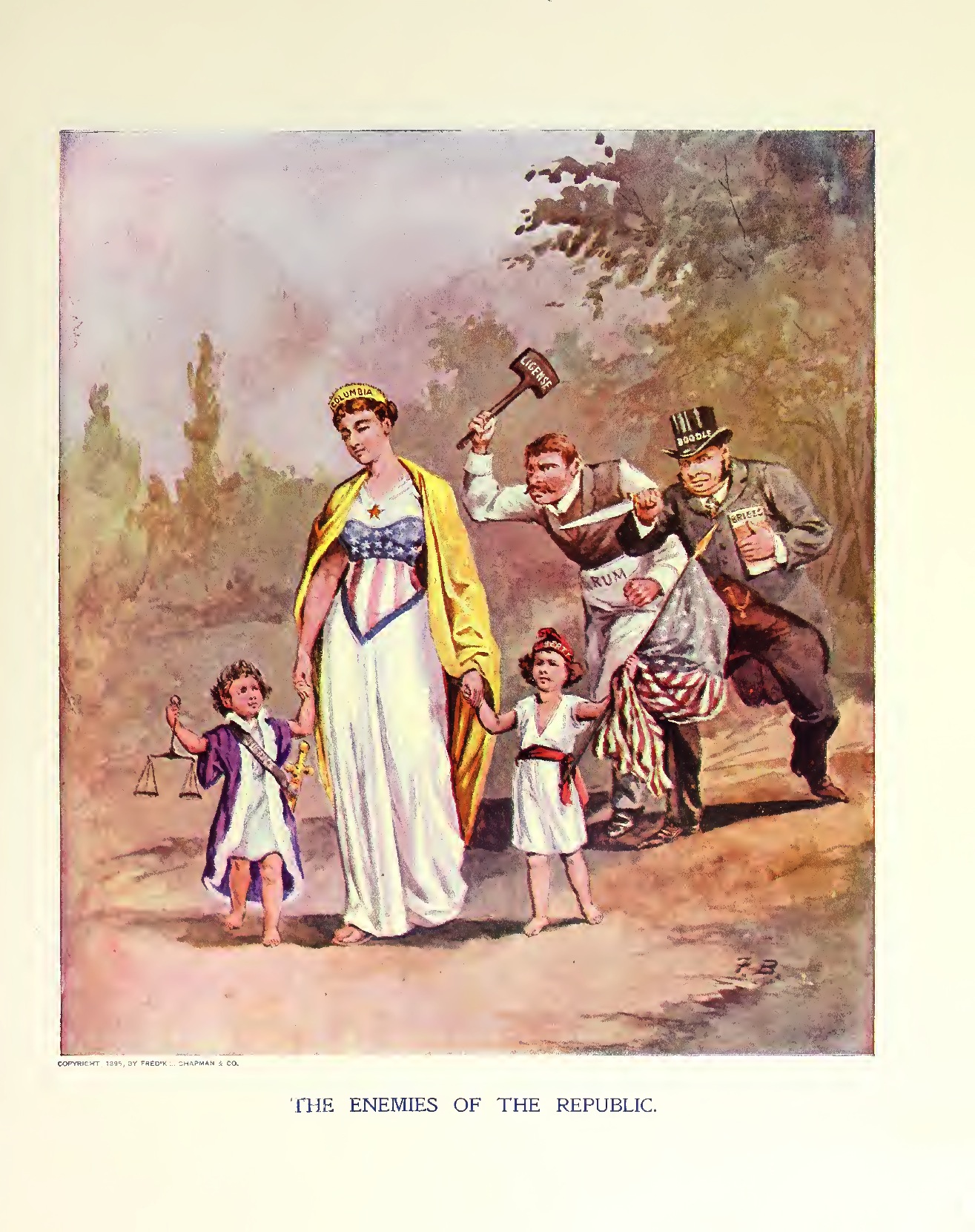

“Enemies of the Republic” shows a rum seller and politician waiting to ambush innocent Columbia and her children, Justice and Liberty.

FRANK BEARD’S FIRST CARTOON.

“Do you remember what that first joke was, Mr. Beard?”

“Yes,” replied the cartoonist, with a laugh. “It was not the most elegant, but it was such as a schoolboy might naturally originate. It represented a lean, old schoolmistress, with a spelling-book in one hand and a ruler in the other, sitting before a little boy perched upon a bench, who was saying his spelling lesson. Under it were these words:“Teacher- Bobby, what does b-e-n-c-h spell ?”

“Bobby- I don’t know, mum.”

“Teacher- Why, what are you sitting on ?”

“Bobby- I don’t like to tell.”“My other schoolboy efforts were somewhat similar, such as any schoolboy might originate. One, for instance, was a professor, reading from his lecture, with a little girl standing beside him with a statuette of Bonaparte in her hand. The professor meditatively exclaims: “Analyse or break the bony part and the inside will be found to hollow out.” Following this were the words: “So Ann Elizar breaks the Bonaparte, but presently hollers out herself.” I continued making cartoons like this throughout my schooldays. It didn’t pay much, however.

“You were in the army, Mr. Beard; how could you pass the examining board, with your deaf ears?” I asked.

“That is quite a story,” replied Frank Beard. “I tried to pass the officers, but failed. I was just 18 when Fort Sumter was red upon. With the first shot an epidemic of patriotism broke out all over the North. Everyone wanted to go right away and fight for his country. I got the epidemic and was crazy to go. I went down to Camp Dennison near Columbus, Ohio, and attempted to pass the examiners. This was at the first of the war, and they were more particular then than later on. I knew they would not pass me if they discovered I was deaf, so I learned the order of the questions and committed the answers to be given to them. I met a number of men who had been examined, and I thought I had it down pat, when I went in. It happened, however, that one of the board had heard something of my infirmity, and at his whispered suggestion the order of the questions was changed. Instead of asking me my name the first question was:‘How old are you?”

“Frank Beard,” I boldly answered.

“What is your name?”

“Eighteen years old,” was my reply.“This went on for perhaps half a dozen questions, when the officers burst into laughing, and I saw that it was no go. I hung around the camp for a short time, and was about to go back home in despair, when one of the captains took pity on me. He told me that I might go with his company without pay, and that he would get me a uniform and a musket. He did so, and I served through the war as a private without pay. I did some sketching, but not much, and made just about as much out of my pictures as I would have received from Uncle Sam had I been on the regular pay-rolls. This seems rather extraordinary now. You can hardly understand it. It was not strange in 1861. Patriotism was then alive. The country was on fire with it. There were thousands of young men who would have done the same.”

“What was your regiment?”

“My regiment was the Seventh Ohio. We had a rather serious time during some parts of the war. A number of our officers were killed, but I escaped without being wounded. I underwent all the duties of a private soldier, though the officers were very lenient with me, on account of my receiving no pay.”

AS AN ARTIST PRIVATE.

“You must have had some curious experiences?” I said.

“No, not particularly so,” replied Frank Beard. “My life was that of the private soldier. I had perhaps a few more privileges than some others, but not many. I remember one funny thing which occurred during the campaign in West Virginia. Lieutenant-Colonel Creighton was in command of our regiment. We were on a hard march, and we had gone for nearly a day without water. I was very thirsty and I noted that the colonel’s Negro servant had a load of full canteens on his back. I concluded to have some of that water, and I assaulted him and grabbed a canteen. The colonel saw me, and he came up and asked me what I meant by such action. I replied that I was thirsty and that I was bound to have a drink. I said, “You fellows riding along on your horses don’t know how we fellows on foot suffer. You ought to get down and try it, if I had a horse like you, I wouldn’t grumble, and I wouldn’t growl at the fellows who grabbed at canteens to save their lives.”

“Well,” said Colonel Creighton, “why don’t you get a horse?”

“I would if I could,” I replied, “but if I did you would not let me ride it.”

“Yes I would,” was the rejoinder.

“Then where can I get one?”

“There is a cavalry regiment just behind us,” replied Colonel Creighton. “It is in camp over there, two miles away. Why don’t you go there tonight and take this one?”

“He said this, of course, in a joke. There was much liberty allowed between officers and men at the beginning of the war, and he had no idea that I would carry out his suggestion. That night, however, I slipped out of camp and went to the cavalry regiment. I took the best horse I could find and brought it back with me. Before morning the cavalry regiment was ordered to march on, and no inquiry was ever made about the horse. He had the letters U.S. branded upon him, and he was a first class animal. The colonel carried out his promise and didn’t object. I rode him for more than a year, and it was only through my peculiar position as an artist private that I was permitted to do so.”

THE FIRST GREAT WAR CARTOON.

“The war was practically the mother of American newspaper caricature, Mr. Beard, was it not ?”

“Yes,” was the reply. “The illustrated newspaper grew rapidly during the war. Before it the only cartoons of much account which we had, were in the paper which I spoke of, known as the ‘Yankee Notions.’ It is true there were cartoons, but they did not appear in the newspapers. They were drawn and lithographed and sold by the sheet. The cartoon most in vogue prior to the war consisted of stilted figures, with words coming out of their mouths, and the words and not the pictures told the story. I think I am the author of what was, perhaps, the first war cartoon. It was in 1861, and it represented a Southern march on Washington. General Scott was in command of the army, and was defending the capital. The rebels were threatening to march to the North. I made a cartoon representing General Scott as a big bull-dog, with a cocked hat on its head, sitting behind a plate containing a bone marked ‘Washington.’”

“Back of him were some tents and the American flag. In front of the bone, and trembling in fear, cowered a lean, hungry hound, labelled ‘Jeff Davis.’ This hound was looking at the bone, but it feared to seize it. Under the cartoon were the words, “Why don’t you take it?” This cartoon made a great hit. It was lithographed, and we sold it in Cincinnati for 10 cents a copy. It was copied all over the country. It made a great sensation. The newspapers published it, and the commercial houses had cuts made from it and put on their envelopes. Had I had the sense to have copyrighted it I would have made a great deal of money out of it. But I was a boy then, and did not know as much as I do now.”“What did you do after the war closed?”

“I went to New York and made sketches for the Yankee Notions. I did work on a number of different papers, and tuned my hand at anything I could find to do in the way of sketching. I had a bad time at first, and sometimes I nearly starved. I have walked the streets night after night in New York because I had not enough to pay for lodging, and I have made many a lunch off crackers and cheese. I could have gotten money, of course, by sending home, but I was too proud to do so. After a while, however, I got a foothold, and I did work on nearly all of the illustrated papers.”

THE AMERICAN CARTOON.

“Tell me something about cartoon making in America ?”

“The first paper that published cartoons was the Yankee Notions of which I told you. This was owned by a man named Strong, and it had a long run. Then Nicknacks appeared, which was followed by the Comic Monthly and Frank Leslie’s Budget of Fun. Then we had Vanity Fair and then Mrs. Grundy, illustrated by Thomas Nast and published by Harper’s. Puck and Judge were later creations, and now the daily newspapers are publishing their cartoons.”

“Speaking of the cartoons in the dailies, Mr. Beard, do you think it has come to stay ?”

“Yes,” was the reply. “Pictures tell a story so much quicker than anything else that they will always be in demand. They have increased the circulation of the daily and Sunday newspapers, and they are improving in quality right along. I believe they will continue to improve, and that invention will make such processes of printing that they will be able to produce good work in the daily papers. I think the demand for good sketches increases. Printing must be illustrated nowadays, and the cheap processes will make an increased demand.”

MORE MONEY FOR ARTISTS.

“What is the effect of this on artists and illustrators ?”

“It increases their value, of course,” replied Frank Beard, “But it also brings up a great crop of new sketchers and of mediocre men. By the poor processes of printing now used in the papers the sketches of the best artists look scarcely better than those of the amateurs who scratch out pictures on the chalk plates in the country newspaper offices. Take Dana Gibson’s pictures. They would lose half their force if published in the daily newspapers instead of the magazines. Still, the increased demand helps the better artists too. Prices are twice as high now as they have been in the past, and the demand for drawings has never been so great as it is now. It is easy to find a man who can draw. It is hard to find one who can tell what to draw. What the world needs is men with ideas. We want creative men, and such men receive higher prices every year. They will be worth more and more as time goes on. Machinery does not hurt them. The only factory that can turn them out is God Almighty.”— “Frank G. Carpenter.”

Via: John Adcock, OSU

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.