Robert Mitchum left home when he was fourteen. He didn’t run away like he later claimed in TV interviews when he was more famous and the conversation needed a little spin to keep it going. His mother packed his suitcase and made him a sandwich for the journey. School couldn’t teach Mitchum anything anymore and he’d had his fill of reading. He had wanderlust and a head full of poetry about life on the road.

Travelling was in his blood. His father was a knuckle-punching Irish immigrant who’d been crushed to death in a freak railway accident–two carriages squeezed him till he popped. On his mother’s side, he had a Swedish captain grandfather who’d escaped from a shipwreck with four others in a lifeboat. When rescued a month or so later, the old sea captain was the only one left. It was long rumoured he had eaten his fellow crew members to survive. Nobody knew the truth, they were too scared to ask.

Mitchum (1917-97) left his sister’s home in New York. He hopped a freight to who knows where. Life was an adventure to be gained and this was how it would start. He rode flatbeds, freight cars, refrigerated trains, teeth-chattering, knees-knocking, met old timers who knew no other life and gave him advice on what to do, and who to avoid, how to steal food and clothes, hunt squirrel, panhandle, and keep clear of the law.

This was an education. This was the hobo life Mitchum had read about and long-wanted to follow. He felt at home among these outsiders, though some of them thought him no more than a tourist, a “scenery-bum”, just along for the ride. Near train stops and train yards, he’d find hobo hideouts and sit by fire light listening to stories told by world-worn travellers.

Sometimes he stopped for a week or more at different towns and cities, taking work as fruit-picker, dishwasher, ditch-digger. In Pennsylvania, he was given accommodation and food by a maternal old dear who said her brother would find him work down the mines. A nice house, a warm bed, food on the table. It was too good to resist. The brother brought Mitchum to the mine. Down in the dark, on hands-and-knees, crawling along a tunnel of three feet or less, chiseling lumps of coal. Dust catching throat, nose, and eyes. Mitchum panicked. Claustrophobia. He had to get out. Scrambling backwards, legs trembling, cold sweat on skin. He started running back towards the mineshaft. A big Polish foreman punched him on the chest (“You no quit!”) swinging a twenty pound hammer with a threat to flatten his skull. Mitchum went back. He worked the job until he’d made enough money to pay the kind old lady and her brother for their help. Then he skipped town.

His mother wrote him letters sent c/o the post office at different cities across country. His mother sent money, tinned food, and clothes. I hope these fit you okay, as I don’t know how much you’ve grown. He’d sit outside the post office reading her words, a tear beading his eye as he thought of home. He might have imagined he was all-grown-up but he was still fourteen and a mother’s kindness unravelled any sense of adulthood.

One night, he arrived off a train with a bunch of other hoboes at Savannah, Georgia. He was cold and hungry and his body sore from lying cramped for hours on a hard wooden flatbed. He was going to get some food when a big hand grabbed his collar and told him he was under arrest. “What’s the charge?” “Vagrancy. We don’t like Yankee bums around here.”

The fat cop whacked Mitchum hard with his nightstick. He hit him again, punching the tip into his ribs. Mitchum gasped. All the air knocked out (Stop yer whinin’ or I’ll give you somethin’ to cry about).

The cop picked Mitchum off the dirt. Slammed him against the cop wagon and whacked him once more for good luck. Mitchum was “a dangerous and suspicious character with no visible means of support.” He was busted for that most common of crimes–poverty.

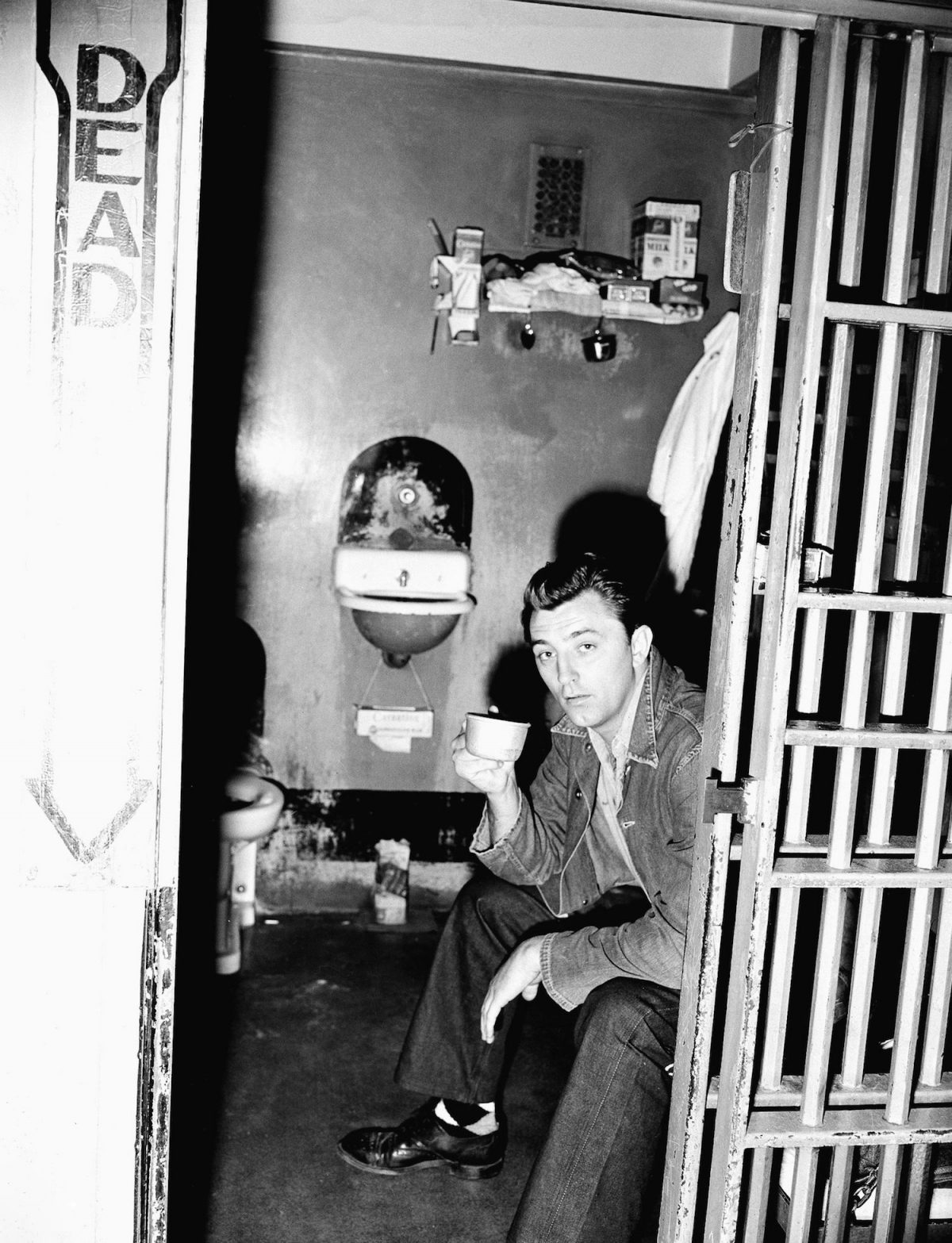

Mitchum was held in a sweaty walled cell. He lay on his bunk wondering about home, wondering what was gonna happen next. After three days, he was pulled up before the judge. The cops had decided to pin a robbery on the teenage felon and told the judge the charges against Mitchum were vagrancy and robbery of a shoe store.

Judge seemed disgusted that someone so young, so inncoent-looking had fallen so far. (You’re just a little piece o’ chickenshit, ain’tcha boy?)

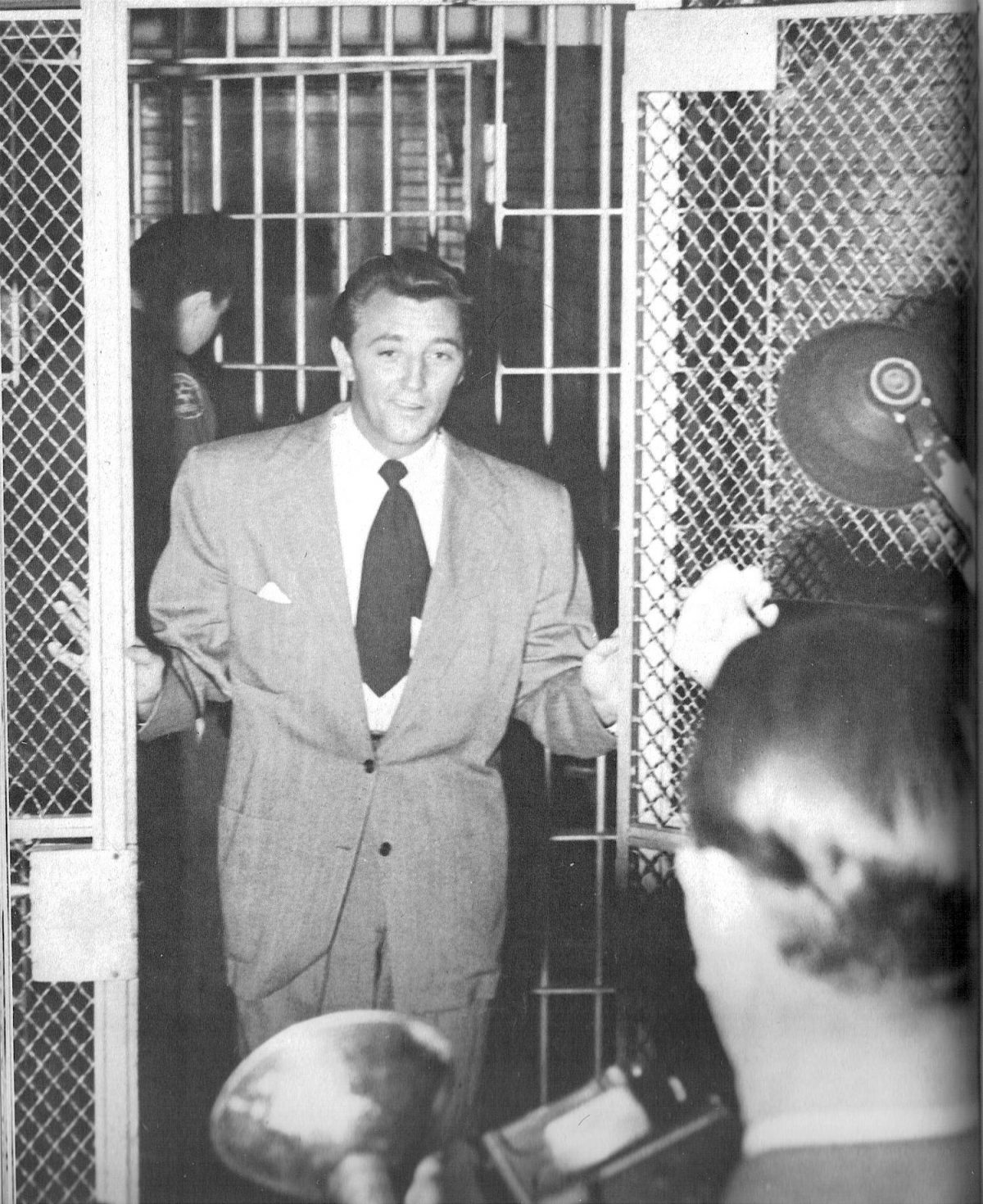

When the judge cross-examined Mitchum, it became apparent he could not have committed the robbery as he was in a police cell at the time. The folks in the courtroom all yuk-yukked at that one. The judge slammed his gavel (Don’t you be disrespecting my courtroom). He was pissed at the cops for being so dumb (Goddam morons). The vagrancy charge stood. Mitchum was sentenced to seven days with the County (And let that be a lesson to you, boy).

Seven days in County was a life sentence. Once a man was convicted of a felony and placed on a chain gang, there was no way back. The guards would come up with some petty little misdemeanour that meant another 30-days or another year was added to the time. Once in the only way out was in a shallow grave.

Mitchum was sent to Chatham County Camp #1, a nightmarish hellhole situated in the middle of the mosquito-infested Pipemaker Swamp. On arrival prisoners were given a list of commandments. You shall not do this. You shall do that. Mitchum spent his first night lying on the floor of his cell next to an old-timer who was coughing up the last of his lungs.

Prisoners at Chatham County Camp #1 were placed on a chain gang and hired out to the County to build roads, dig ditches, carry out those shitty jobs the County didn’t want to spend too much money on. It was good business for the prison and for the County. Prisoners were worked at least twelve-hours a day, seven days-a-week for one meal a day.

The prison was an open laboratory of disease. Every other prisoner was sick with something. TB. Cancer. Swamp fever. Gangrene. When Mitchum was taken out on a chain gang detail the guards fastened the leg irons so tight they cut into his flesh. A day or two later, an infection bruised his skin and a harvest of yellow pustules blossomed from heel to knee.

Mitchum knew if he didn’t get out, he was going die in jail. He asked some old lags about escaping. They told him of that one guy who once ran off, but see that Captain Fry over yonder? Yeah him with the gunk in his eyes, you think he’s blind? Well, he just picked up his rifle and doggone blew that sucker’s head clean off. Body lay in the field for a day or so ’til we had to go peel it off the soil.

His leg was getting painful. If he didn’t make a break soon, his number would be up.

On road detail, the guards unfastened the prisoners’ leg irons to allow them to shovel gravel and rake tar across the road. There was about one hundred yards from the road to a clump of trees and a wood leading out of the County. Mitchum watched Captain Fry polish his rifle, mumbling inane shit to himself.

As it neared the end of the day, Mitchum positioned himself around twenty yards away from Fry at the back of the detail. Two guards were smoking, talking to each other. Captain Fry had his legs stretched out, rifle across his thighs, with a look like he was off in some deep reverie about the meaning of life or whether he was getting fried chicken for dinner.

Mitchum turned. A bolt of pain shot the length of his infected leg. He ran. He managed about thirty maybe forty yards before a shout rang out. Get back here, Goddamit. Mitchum ducked. Zigged, zagged, ran straight for the dark of the trees. A shrill whistle. Something breathed past his face. A gun cracked. Fry’s shot had missed. Mitchum ducked and ran head down. Another crack. More shouts. Mitchum made it to the woods.

He kept running. The shouts were far away now. He came near a town and stole clothes off a line. Limped along the highway thumbing a lift up to Baltimore. He was getting sick. The poisoning was going through his body. He wrapped his leg in rags. Every morning when he peeled back the pus filled cloth, his leg was a darker colour, a deadlier colour. He found refuge with a gang of runaways. They spent their days stealing dogs, then waiting for the reward posters to go up before returning the pooch to its grateful owner.

His leg was getting worse. It throbbed like it had a heart of its own. He lay down one night and wrote a postcard to his mother:

Trouble lies in sullen pools along the road I’ve taken.

He continued hitching rides. But his infected leg with its blood-stained and pus-stained bandages made most folks drive on. In Pennsylvania a kindly doctor stopped. He looked at Mitchum’s leg, gave him some pills, and drove him all the way to his mother’s house in Rising Sun, Delaware.

The doctor told Mitchum’s mother “If you love your son, the best thing to get him to the hospital and get that leg taken off.”

Mitchum’s mother thought differently. She washed the limb and applied poultice after poultice. Mitchum had a fever that lasted a week. His mother tended to the leg. Each new poultice taking a little bit more of the poison away. The swelling went down, the leg paled. A week or so later, Mitchum woke. The fever gone, the poison gone, his leg still attached.

Mitchum had had his adventure, and a lesson learned.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.