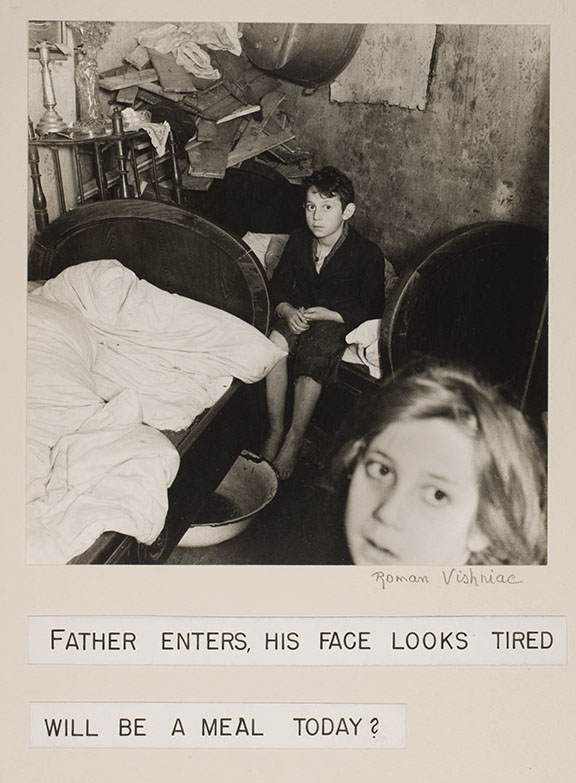

“These are the faces of children I embraced and kissed and loved. I cannot imagine that they are dead, that none would survive… A million and a half children among the six million… But this I knew… I wanted to save their faces, not their ashes” – Roman Vishniac

From 1935 to 1938 Roman Vishniac worked for the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) photographing Jewish communities in central and eastern Europe. The aim was to stimulate philanthropy on their behalf. The JDC is a relief agency set up to help Jews in peril. We see the city and shtetl as home to besieged religious and poor Jews. We see the children engrossed in cheder classes.

But that wasn’t all. Not all Jews were impoverished and bent over religious texts. Not all Jews saw themselves as misfits, victims and scapegoats. There was not and there never will be a Jewish standard. The Jews thought they were fine and then it changed. Suddenly obeying the letter of the law took the place of humanity, solicitude and kindness.

Vishniac had his own mission. “My friends assured me that Hitler’s talk was sheer bombast,” Vishniac said in 1955. “But I replied that he would not hesitate to exterminate those people when he got around to it. And who was there to defend them? I knew I could be of little help, but I decided that, as a Jew, it was my duty to my ancestors, who grew up among the very people who were being threatened, to preserve – in pictures, at least – a world that might soon cease to exist.”

Russian-born Vishniac had read Hitler Mein Kampf in 1923. He had seen the graffiti ordering “Jude Verecke!” on walls in his adopted city of Berlin. He had noticed impoverished, embattled Jews when he was a boy living in Moscow. “They had a special kind of face, those people, a special kind of whisper and a special kind of footstep,” he told The New Yorker in 1955. “They were like hunted animals.”

His work would become a photographic record of a world on the brink of annihilation. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic, called Vishniac “the official mortuary photographer of Eastern European Jewry.”

Of course, with our knowledge of the Holocaust, the pictures become preludes to destruction, neatly bookending Jewish life before and after the horror in Shoah’s grip. But that one view, however apt, is lazy. Unlike the German Nazis, the pogromshchiki and the plain bigots for whom Nazism presented a haven for murderous hate, Vishniak’s pictures are neither exploitative nor monocular. They reveal an empathy and warmth for the subject. Vishniac was aware of rising State-sponsored anti-Semitism, but he did not foresee mass murder. His work is valuable because it offers us a view on what life was like at a certain space and time, with all the uncertainties, vices, pain, contradictions and normality of then as now.

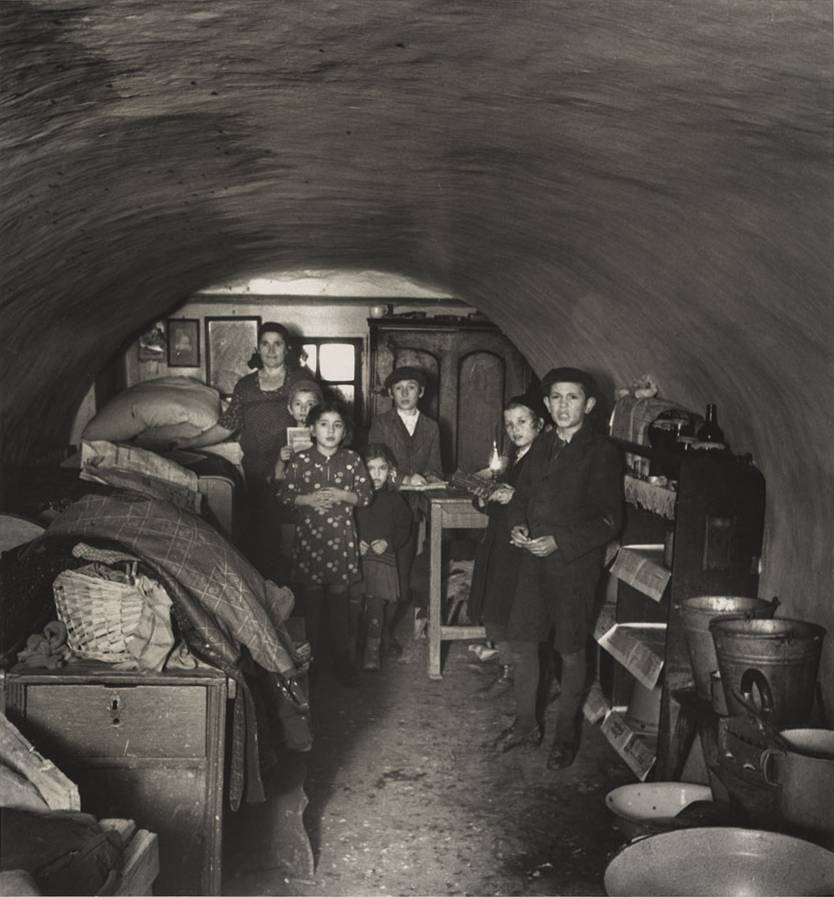

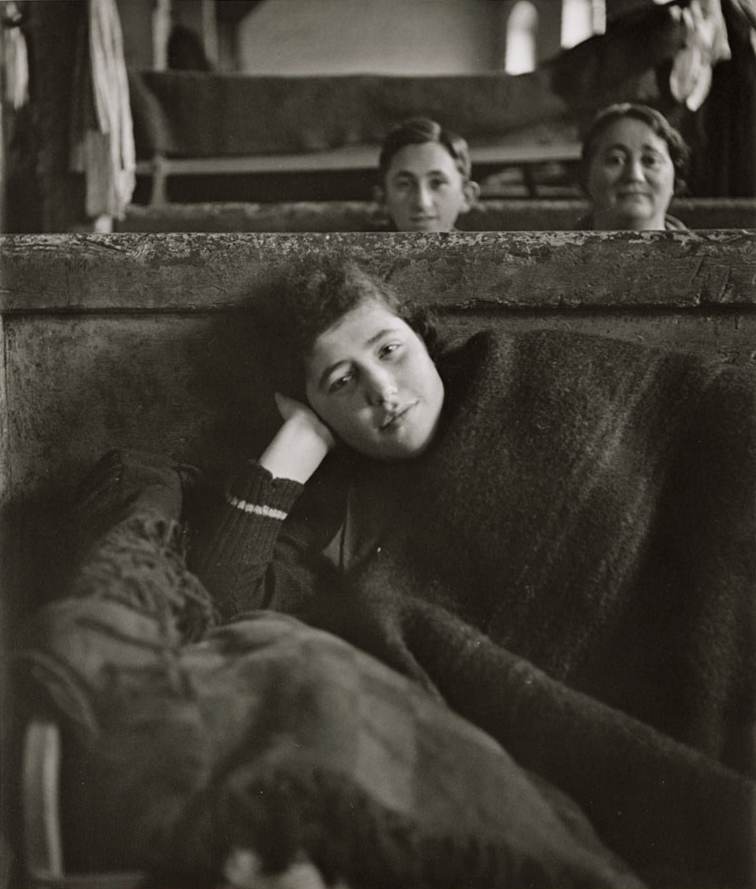

Jewish refugee in military barracks that have been converted to living quarters, Polish detention camp in Zbaszyn

On October 27, 1938, the German police and military arrested 17,000 Jews of Polish nationality or descent and forcibly transported them to the Polish border. The Polish authorities refused to admit them and roughly 9,000 Jews, including children, pregnant women, the elderly and infirm, were trapped in the small Polish border town of Zbaszyn, where they lived in filthy horse stables and abandoned military barracks as winter fast approached. Disease was rampant, and many died of pneumonia. Vishniac later described Zbaszyn as “a no man’s land.” The Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) quickly responded, creating a refugee camp, and commissioned Vishniac to document the plight of Zbaszyn’s refugees. Distraught by the suffering of his parents at Zbaszyn, Herschel Grynszpan, a German-born Jew of Polish descent, went to the German Embassy in Paris and assassinated Nazi official Ernst vom Rath. German authorities used the assassination as a pretext for Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, an antisemitic pogrom that took place throughout Germany on November 9–10, 1938.

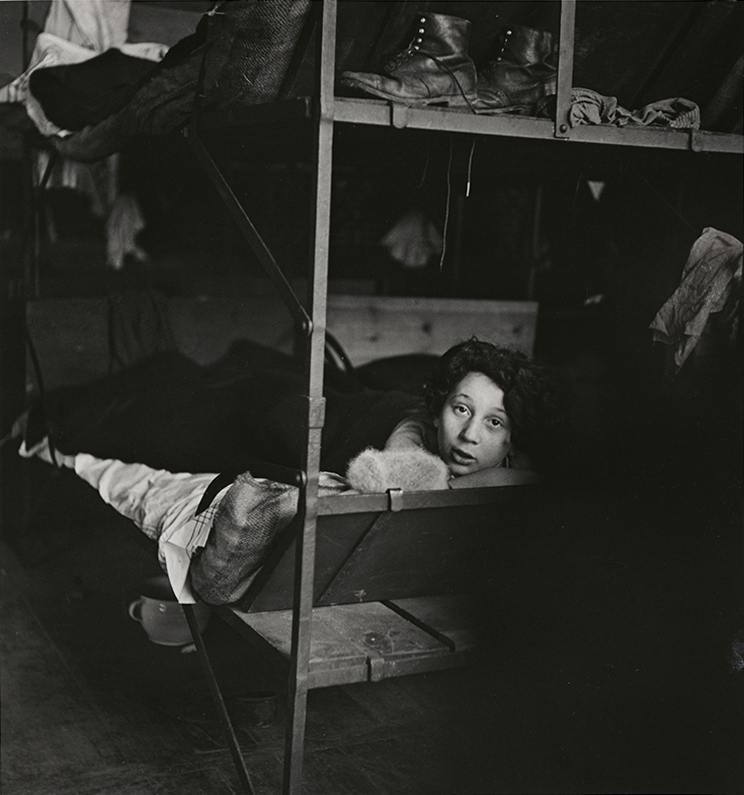

Jewish refugees in horse stables that have been converted to living quarters, Polish detention camp in Zbaszyn.November 1938

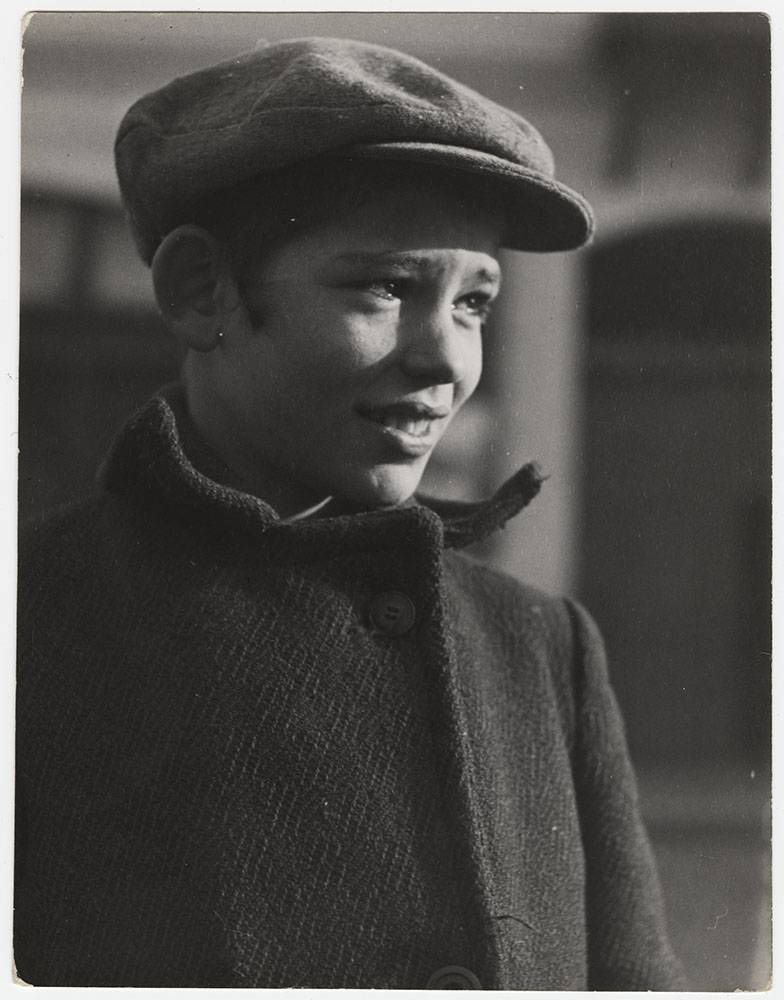

Vishniac’s photograph of Nettie Stub, taken in Zbaszyn, was put on the wire along with several of his Zbaszyn photographs and picked up by the Red Cross. Later that year, Stub was rescued and brought to safety in Sweden by the Red Cross, along with several other children. In 1983,Stub, then living in the Bronx as Nettie Katz, noticed this picture of herself in Vishniac’s seminal publication A Vanished World. She contacted the photographer and told him that she believed the Red Cross chose to save her because of his photograph.

In March 1944, Germany seized control of Hungary and began transporting the Jewish population of Carpathian Ruthenia, including Chaim Mechlowitz, his wife Etel, and eight of their children, to Auschwitz. Chaim, Etel, and all but one of their children were killed there. Four of Mechlowitz’s children from his first marriage survived the war. Chaim’s granddaughter recently donated photographs of Mechlowitz and his family, made around the time that Vishniac took his iconic images of the farmer, to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Portraits of Nettie Stub, David Eckstien, and Chaim Mechlowitz are among more than two dozen subjects of Vishniac’s photographs to be identified and interviewed by the Vishniac Archive at ICP. As the number of living survivors of the Holocaust dwindles, ICP’s efforts to identify individuals and communities documented by the photographer come at a critical time in preserving this history for future generations.

All pictures © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.

![Jewish schoolchildren, Mukacevo] OBJECT NAME 069 DATE ca. 1935-38](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/193_1974.jpg)