“It’s very strange that most of our people were interested in art, had some art training, had desires to be artists, perhaps suddenly discovered photography offered them something…. In that job and elsewhere, I began to realize it was curiosity, it was a desire to know, it was the eye to see the significance around them.”

– Roy Stryker

Canning plant where peas are principal project, Milton-Freewater, Oregon (1941), by Russell Lee

The New Deal wasn’t only a massive feat of political, social, and civil engineering;, it was also a public relations masterstroke convincing millions of Americans to keep thousands of countrymen they’d never meet from going hungry, jobless, or homeless. But for economist Roy Stryker, head of the Farm Security Administration’s “Historical Section,” the work he and his photographers did had nothing to do with PR, and certainly not propaganda. It didn’t even have much to do with photography, he claimed in a 1963 interview, an astonishing statement given that Stryker employed some of the most well-known American photographers of the 20th century and presided over a visual naturalism as influential as the literary work of Charles Dickens and Émile Zola in the previous century.

One of those photographers, Russell Lee, left Stryker “very much impressed” when he applied to the Historical Section after hearing about it from FSA photographer Ben Shahn. Lee went on to travel the country, sleeping in his car, going farther and documenting more of the country than anyone else. But before photography, he “went into industry,” he says, working as a plant chemist after graduating with a degree in chemical engineering in 1925. He married painter Doris Emerick, got “interested in painting on weekends,” and once the job at the plant “got a little boring,” he quit and took up art full time, studying at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco.

Birthday party, FSA farm workers camp, Tulare County, California (1942)

The Lees met Diego Rivera and other modern artists in San Francisco, then moved to Woodstock in Upstate New York in 1931. Doris excelled as a painter, Russell turned to photography and was, remarked FSA photographer Arthur Rothstein, perfectly suited to the medium as a both a trained artist and a chemist. Lee was independently wealthy and didn’t need to work; he was primarily driven by social and political concerns, and a desire to document the country’s growing poverty and despair. He later divorced Doris and married Jean Smith, who traveled with him and wrote the captions for his FSA photographs.

Central Valley, near Shasta Dam, California (1939)

Lee’s name is hardly as renowned as colleagues like Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, or Gordon Parks, but he may be “one of the most influential documentary photographers in American history,” the Library of Congress writes. His work has certainly left its imprint on popular culture;

Stephen Colbert featured Lee’s iconic shot of a young Black man drinking from a water cooler marked “colored” on one of his “Late Show” monologues about racial injustice. Millions of “Cheers” viewers saw his photo of cheerful patrons in a Depression-era Minnesota saloon in the opening credits. Microsoft offered his 1939 photo of a Texas couple as a screensaver in its Windows 98 operating system.

Russell Lee was the most prolific of the FSA photographers (a group Ansel Adams called “a bunch of sociologists with cameras”). Of the more than 60,000 prints held in the Library of Congress’s FSA Collection, 19,000 were taken by Lee. His photographs demonstrate a “talent for capturing images emblematic of early 20th century concerns, including the ecological catastrophes of dust storms and floods, the population shift from rural to urban areas, discrimination against racial and ethnic groups and life on the home front during World War II.”

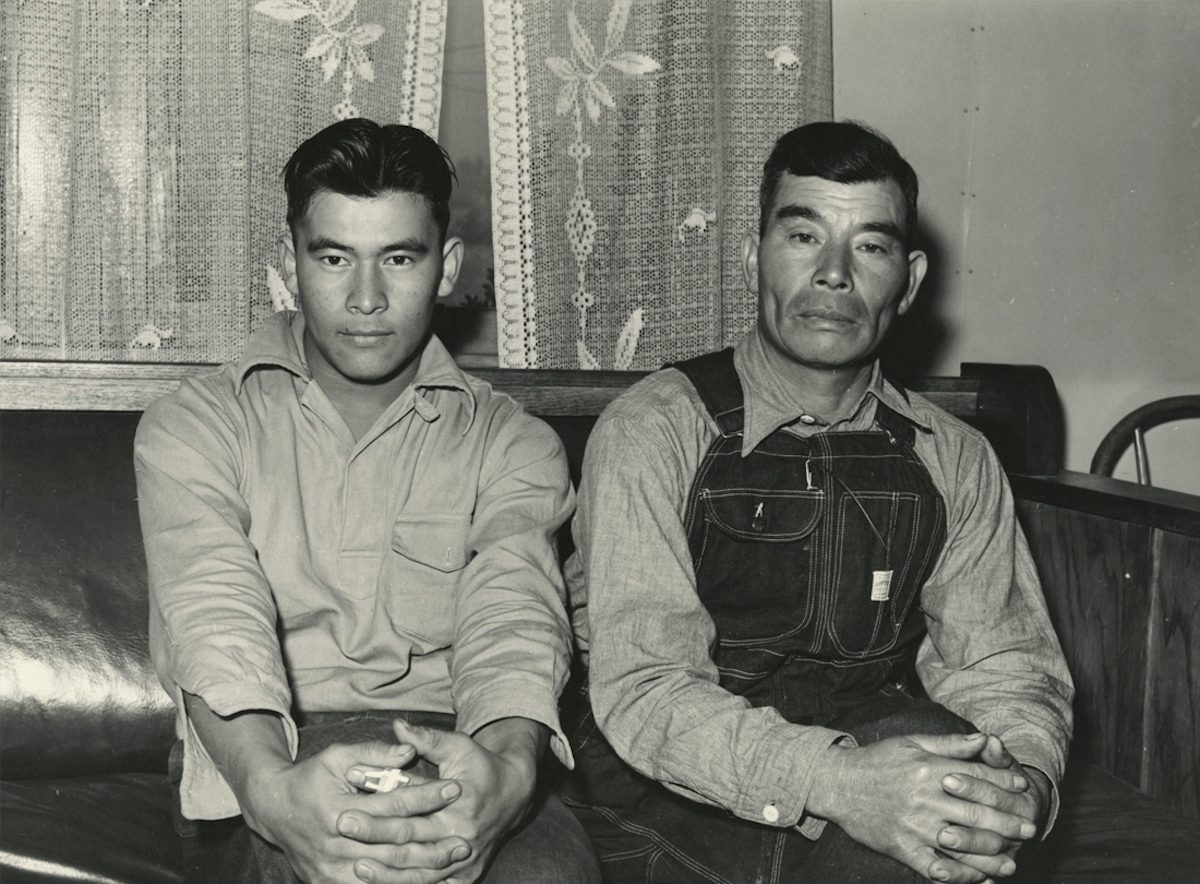

Fruit farmer and son, Placer County, California (1940)

In the spring and summer of 1942, the Lees “began documenting the removal and confinement of Japanese Americans along the West Coast,” writes the Densho Digital Repository. Lee shot “nearly 600 images of Japanese Americans in California, Oregon, and Idaho…. Lee was greatly troubled by what he saw and believed in the importance of documenting this period of time,” a belief shared by Dorothea Lange, who took almost 500 photographs in Japanese internment camps in California.

Child playing piano, Tehema, California (1939)

Lee was adept at capturing the quotidian lives of rural people around the country, with a naturalness and grace born of easy familiarity. “Lee’s small and quiet 35mm Contax camera allowed him to get up-close and personal with his subjects,” writes the Museum of Contemporary Photography. “Even before shooting, he often conversed with them and inquired about their daily routines to establish a trusting rapport…. In this regard, Lee’s sympathetic and meticulous work can be considered a model, encouraging Americans from different walks of life to care for one another.”

Jim Norris and wife, homesteaders, Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

After photographing for the army overseas during World War II, Lee moved to Austin, Texas, where he lived until his death in 1986. His work is available online at the Briscoe Center for American History and the Library of Congress’s digital collections.

Truck load of ponderosa pine, Edward Hines Lumber Co. operations in Malheur National Forest, Grant County, Oregon (1942)

Home of a fruit tree rancher, Delta County, Colorado (1940)

Winner at the Delta County Fair, Colorado (1940)

Hay stack and automobile of peach pickers, Delta County, Colorado (1940)

Distributing surplus commodities, St. Johns, Arizona (1940)

Abandoned brick plant near Muskogee, Oklahoma (1940)

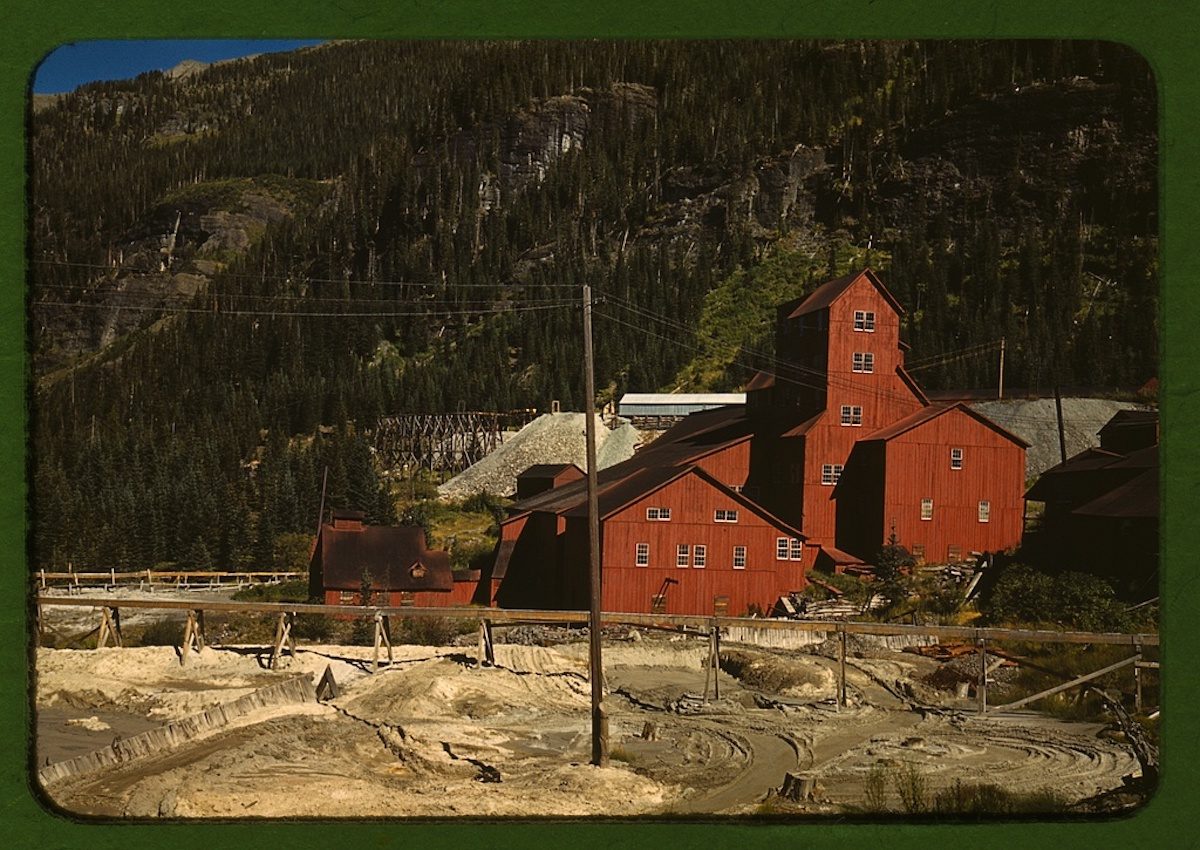

Mill at the Camp Bird Mine, Ouray County, Colorado (1940)

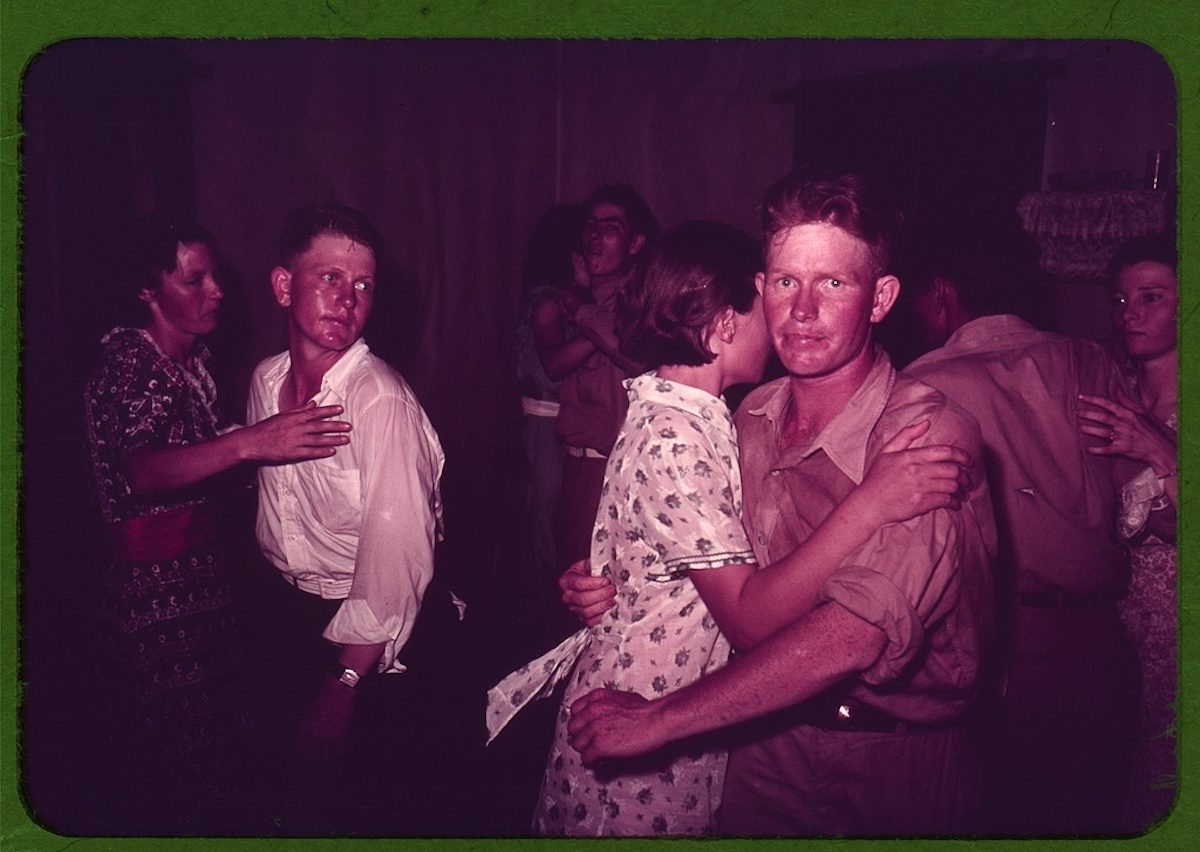

Couples at square dance, McIntosh County, Oklahoma (1940)

Faro and Doris Caudill, homesteaders, Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

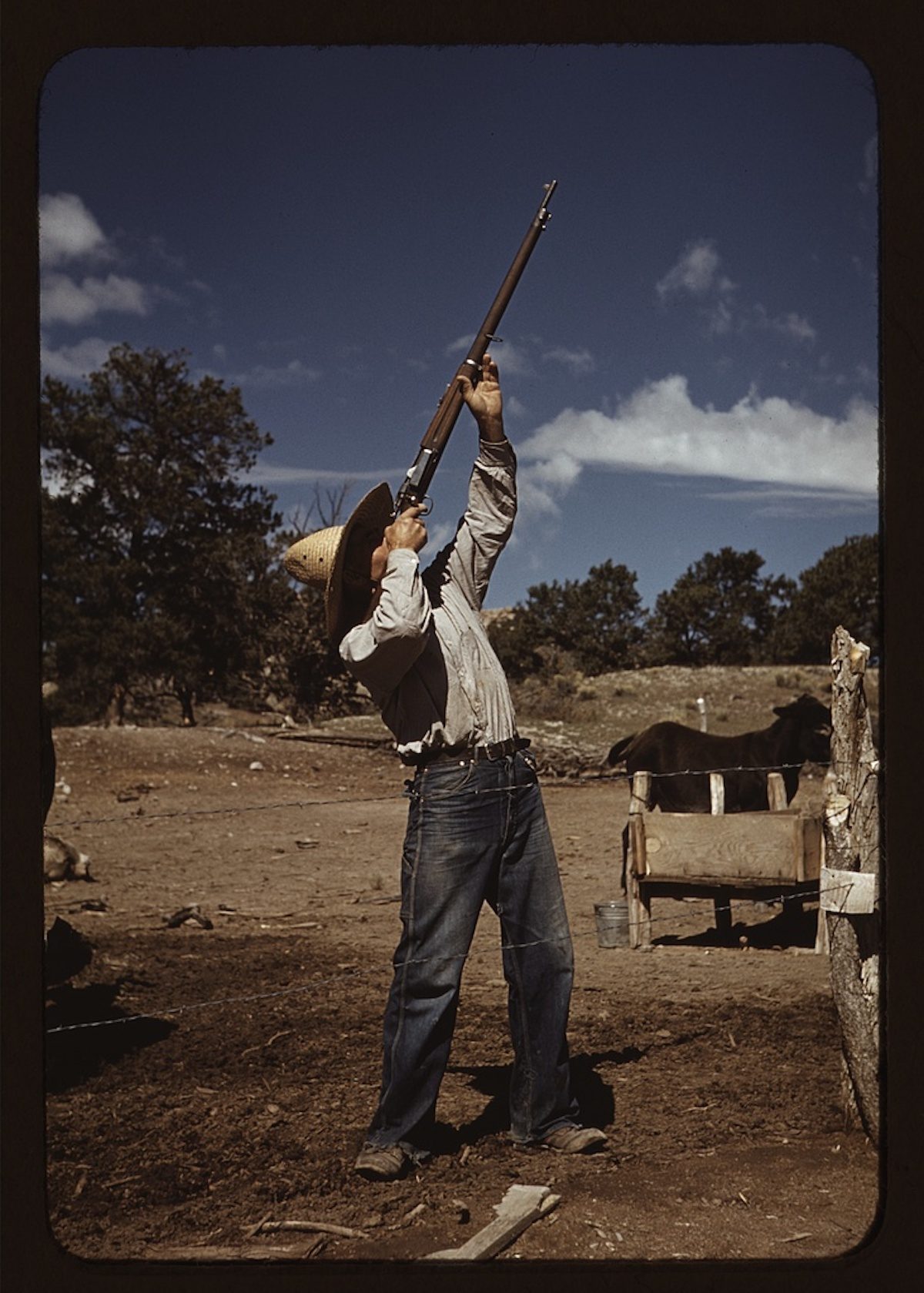

Mr. Leatherman, homesteader, shooting hawks which have been carrying away his chickens, Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

Bill Stagg, homesteader, in front of his barn, Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

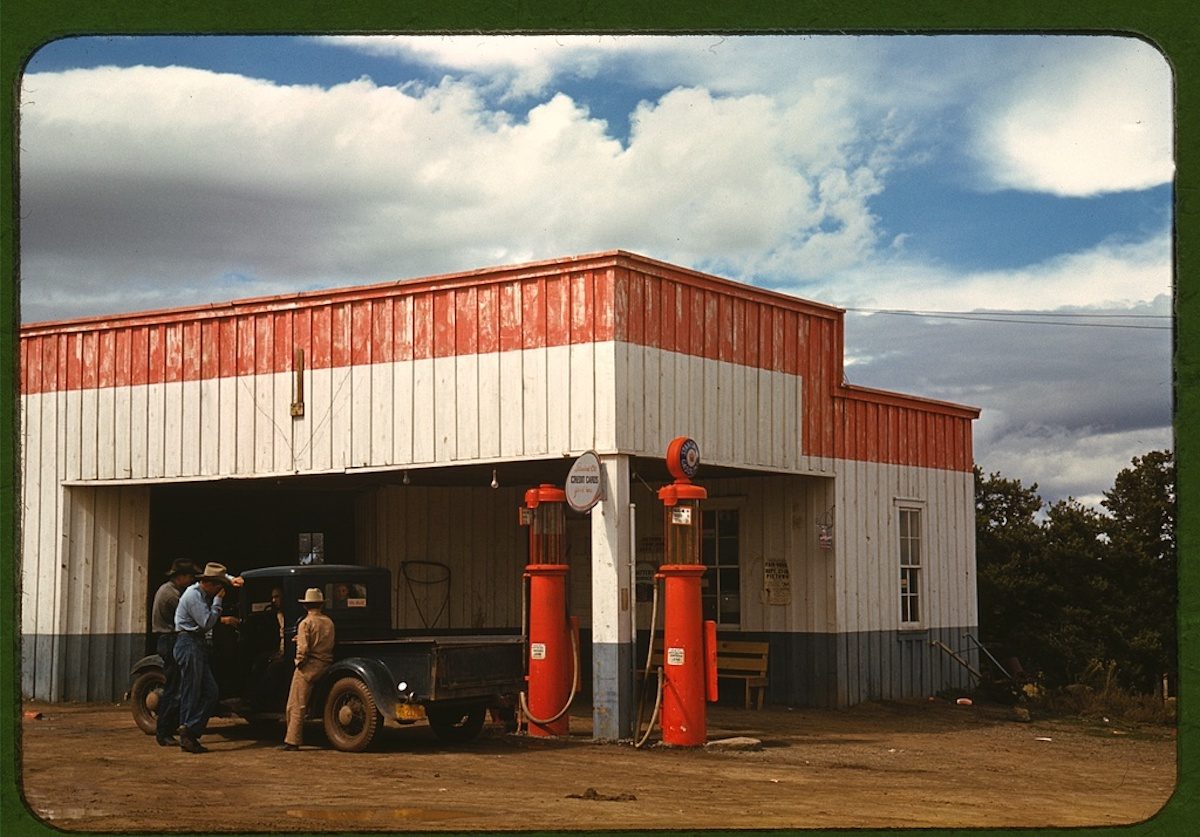

Filling station and garage at Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

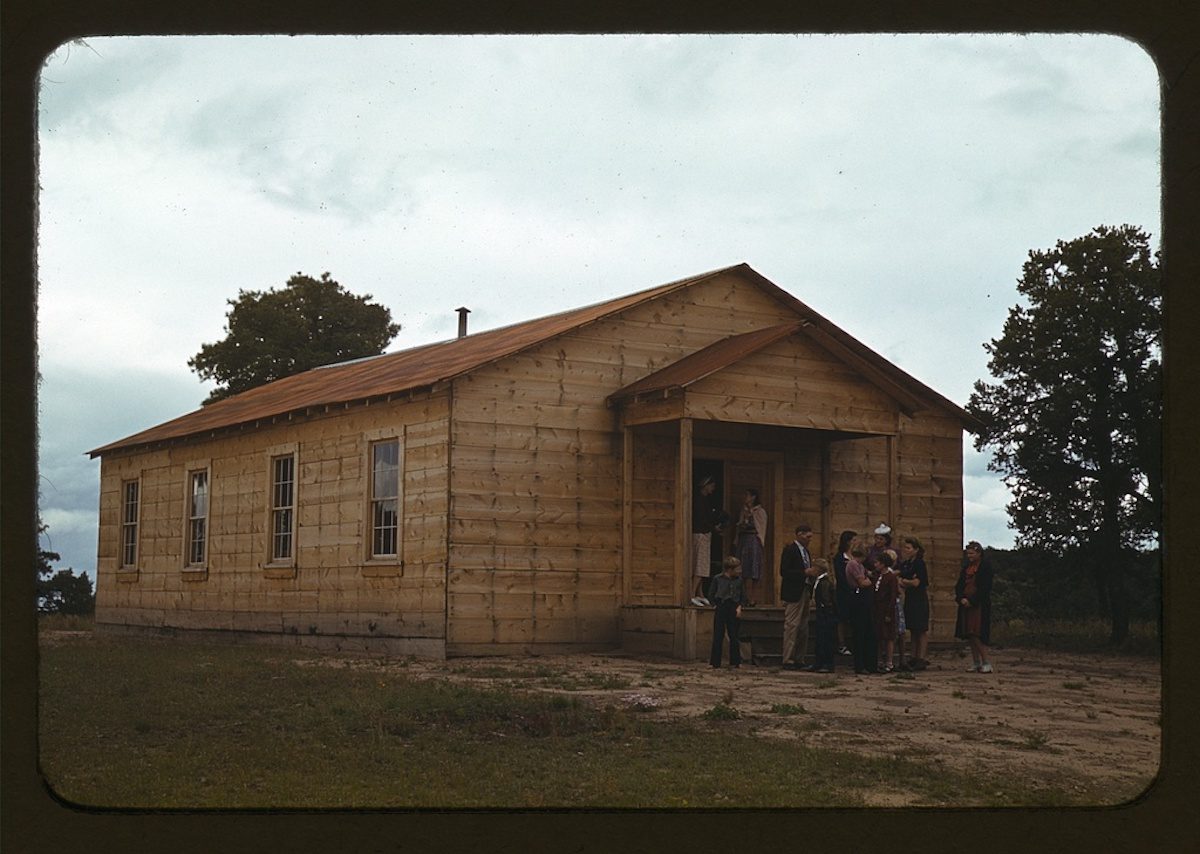

Church at Pie Town, New Mexico (1940)

On main street of Cascade, Idaho (1941)

Japanese-American camp, war emergency evacuation, Tule Lake Relocation Center, Newell, California 1942

Housewife in the front room (1937)

Barbecue, Turlock, California (1942)

Barn (1939)

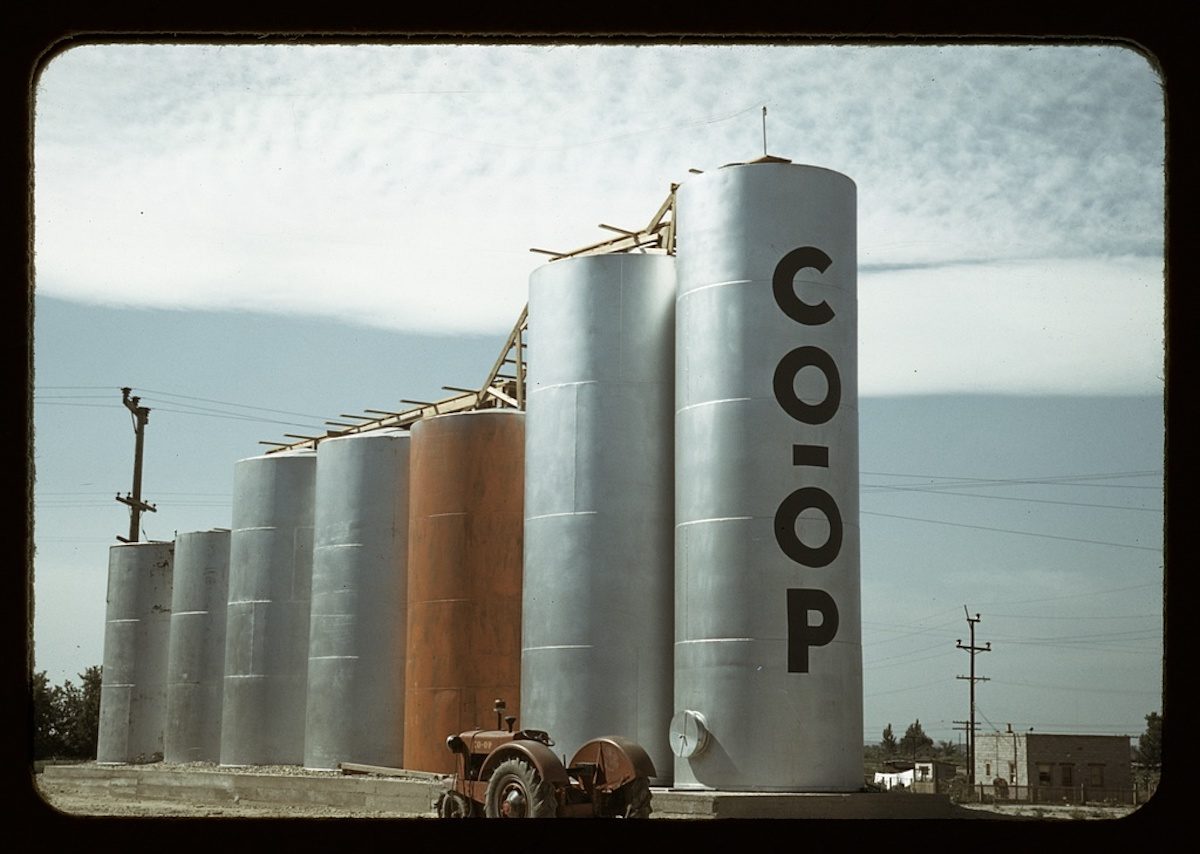

Grain elevators, Caldwell, Idaho (1941)

Buy Prints of Russell Lee’s work in the Shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.