Franklin Price Knott (1854 – 1930) is remembered for taking some of the first color images to appear in National Geographic magazine. Michael Redmon’s biography on Knott in the Santa Barbara Independent tells us the man who travelled the world taking pictures was not raised in riches. Born in Clifton, Clark County, Ohio, Knott was the 10th son of a father who moved from job to job, farm to farm, in an effort to earn a crust. Franklin had talent. He won scholarships to two Massachusetts schools and left the USA for Paris, where he married and worked as a painter of miniature portraits. Problems with his sight triggered other artistic pursuits, turning him towards color photography.

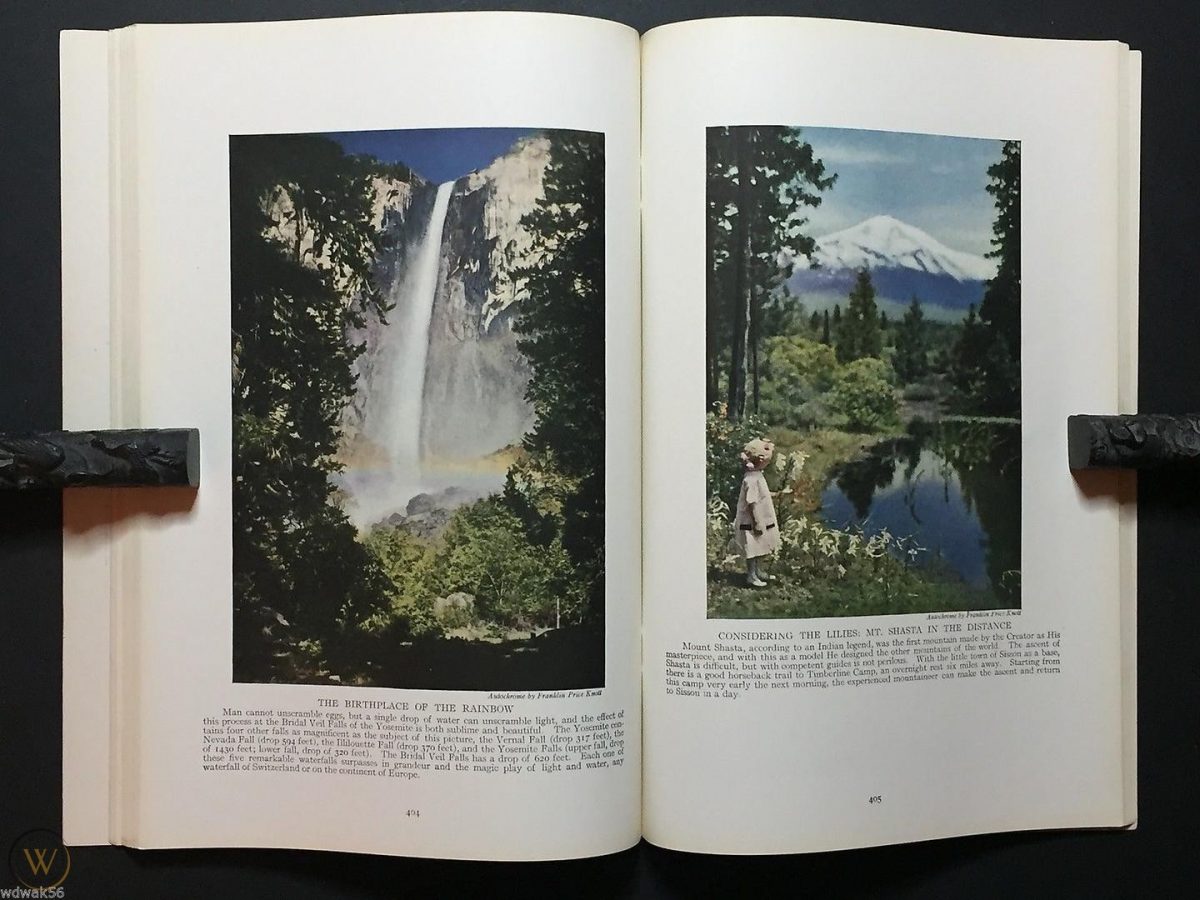

Knott used the autochrome process of color photography, first marketed in France in 1907. In this process, potato-starch grains were dyed in primary colors and then deployed as a filter onto a photographic glass-plate negative. The process was difficult to master. Exposure times were very long; the glass plates were heavy and easily damaged; the camera equipment bulky. If one needed to go out into the field, suitcases of chemicals had to be dragged along and makeshift darkrooms erected for developing the plates. A travel photographer needed to be part artist and part pack mule.

Franklin Knott’s autochromes in ‘Land of the Best : THE LAND OF THE BEST : A Tribute to the Scenic Grandeur and Unsurpassed Natural Resources of Our Own Country’ – National Geographic Magazine, April 1916 – via Worthpoint

The Knotts returned to the US, settling in Santa Barbara, California, around 1910.

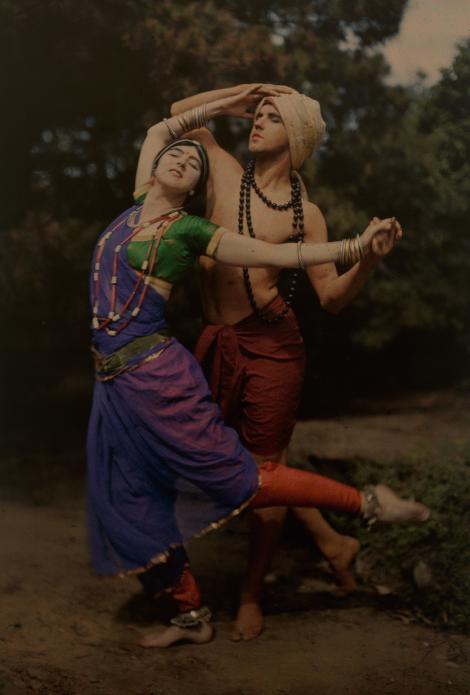

In the April 1916 issue of National Geographic magazine, Editor Gilbert H. Grosvenor authored a paean to the wonders of the United States titled “The Land of the Best.” Accompanying the article were 23 autochromes by Franklin Price Knott. The images included one of the husband-and-wife team of modern dance, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn, who appeared in Santa Barbara numerous times and under whom Martha Graham trained; an image of the Santa Barbara Mission; and a “Sunrise Setting the Morning Heavens on Fire” over West Beach and Stearns Wharf. Another series of autochromes, chronicling Knott’s travels in India, Holland, Tunisia, Algeria, and the U.S., appeared in the magazine in September.

Knott’s wife died in 1926, and in the following year he took off at the age of 73 on perhaps his greatest adventure. The photographer embarked on an extended 40,000-mile tour of Japan, China, the Philippines, Bali, and India.

Land of the Best – 1916

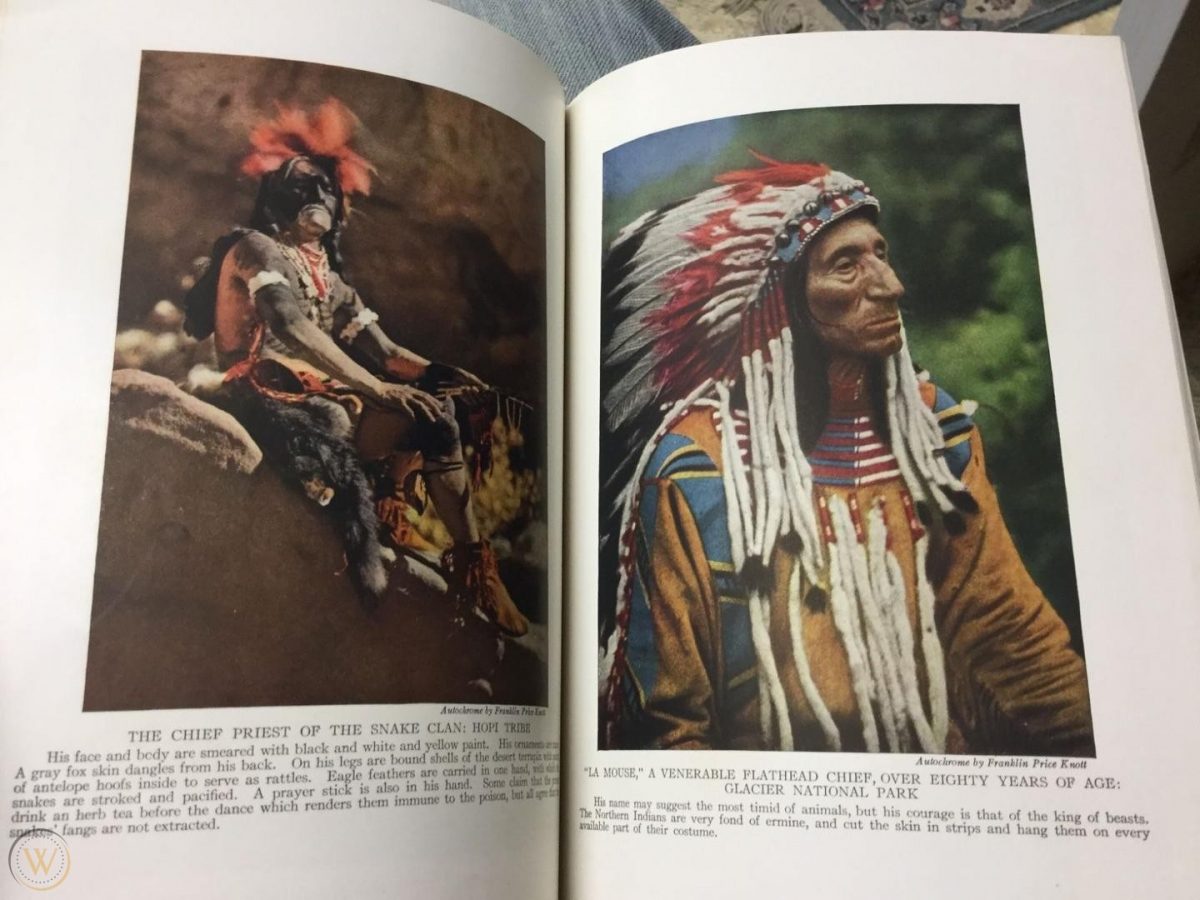

A Hopi Snake Clan priest in Arizona, USA on Sunday 31st March 1912 – two weeks before the sinking of the Titanic; two weeks after Lawrence Oates, dying member of Captain Scott’s South Pole expedition, leaves the tent saying, “I am just going outside and may be some time” – photographed in color by Franklin Price Knott – via BableColour

Many readers would like to know amore of the people in Knott;’s picture. But the emphasis was on the readers not the subject. In 2018, National Geographic issued the following statement: “For Decades, Our Coverage Was Racist. To Rise Above Our Past, We Must Acknowledge It.”

The magazine asked John Edwin Mason, a University of Virginia professor specialising in the history of photography and the history of Africa, to look at the magazine’s archives for signs of racism.

What Mason found in short was that until the 1970s National Geographic all but ignored people of colour who lived in the United States, rarely acknowledging them beyond labourers or domestic workers. Meanwhile it pictured “natives” elsewhere as exotics, famously and frequently unclothed, happy hunters, noble savages – every type of cliché.

Unlike magazines such as Life, Mason said, National Geographic did little to push its readers beyond the stereotypes ingrained in white American culture.

“Americans got ideas about the world from Tarzan movies and crude racist caricatures,” he said. “Segregation was the way it was. National Geographic wasn’t teaching as much as reinforcing messages they already received and doing so in a magazine that had tremendous authority. National Geographic comes into existence at the height of colonialism, and the world was divided into the colonisers and the colonised. That was a colour line, and National Geographic was reflecting that view of the world.”

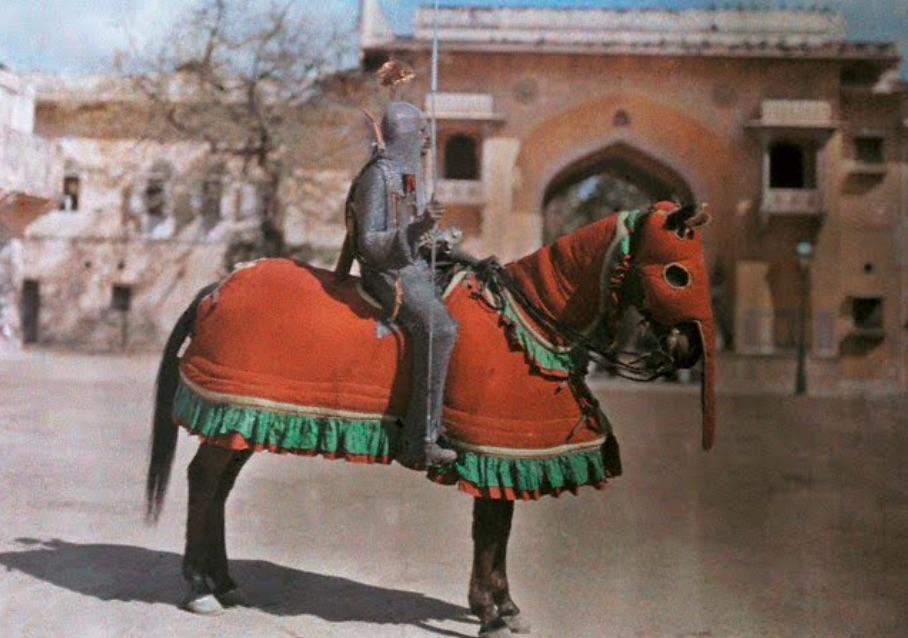

A warrior is ready for a tournament in Jaipur, India. Photography by Franklin Price Knott, 1929

Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis in performance, 1916

“People of colour were often scantily clothed, people of colour were usually not seen in cities, people of colour were not often surrounded by technologies of automobiles, airplanes or trains or factories. People of colour were often pictured as living as if their ancestors might have lived several hundreds of years ago and that’s in contrast to westerners who are always fully clothed and often carrying technology. [White teenage boys] could count on every issue or two of National Geographic having some brown skin bare breasts for them to look at, and I think editors at National Geographic knew that was one of the appeals of their magazine, because women, especially Asian women from the pacific islands, were photographed in ways that were almost glamour shots.”

– John Edwin Mason

A Geisha poses in Kyoto, June 1927 by Franklin Knott

Lead image: Franklin Price Knott, Nine-year-old dancer, Bali. Photographed on Autochrome, via US Department of State.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.