SIR Nicholas Winton is the London-born man who organised the rescue and passage to Britain of about 669 mostly Jewish Czechoslovakian children destined for the Nazi death camps before World War II in an operation known as the Czech Kindertransport.

* “The problem was getting the people who would accept the children, and of course this was at a time when the evacuation of children from the south [of England] was taking place anyway…” he says.

“It’s marvellous that so many people did come forward. The unfortunate thing was that no other country would come along and help. I tried America but they didn’t take any. It would have made a vast difference if they had.”

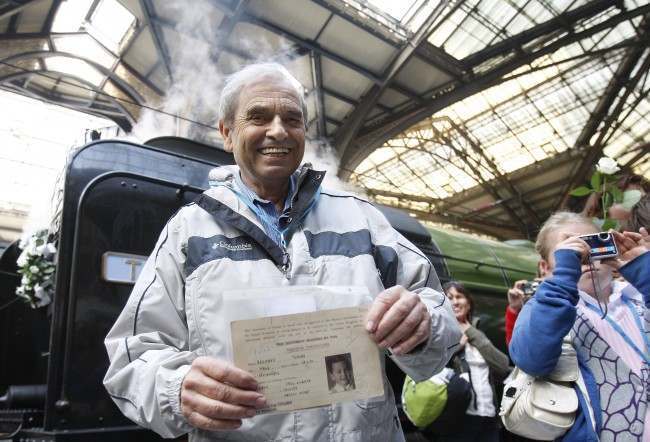

Sir Nicholas Winton, 101, who had organized the rescue of 669 mainly Jewish children by train from Prague in 1939 holds flowers during the premiere of a new movie based on his life story called “Nicky’s Family” in Prague, Czech Republic, Thursday, Jan. 20, 2011.

Just before Christmas 1938 Winton was about to travel to Switzerland for a skiing holiday, when he decided instead to travel to Prague, Czechoslovakia, to help a friend who was involved in Jewish refugee work, and had called him asking for his help. There he single-handedly established an organisation to aid children from Jewish families at risk from the Nazis. He set up an office at a dining room table in his hotel in Wenceslas Square.[9] In November 1938, shortly after Kristallnacht, the House of Commons had approved a measure that would permit the entry of refugees younger than 17 years old into Britain, if they had a place to stay and a warranty of £50 was deposited for a ticket for their eventual return to their country of origin.

Sir Nicholas Winton, 100, meets friends, relatives and the people whose lives he saved at Liverpool Street Station, London. The former stockbroker who saved hundreds of children from the Holocaust by organising trains to take them from Prague to London today said it was ‘wonderful that it did work out so well’. Sir Nicholas Winton, 100, from Maidenhead, Berkshire, masterminded the mass evacuation shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War.

An important obstacle was getting official permission to cross into the Netherlands, as the children were destined to embark on the ferry at the Hook of Holland. After Kristallnacht on 9–10 November 1938, the Dutch government had officially closed its borders to any Jewish refugees, and the border guards (marechaussee) actively searched for them and returned their captives to Germany, despite the horrors of Kristallnacht being well known in the Low Countries, as, for instance, from the Dutch-German border the synagogue in Aix-la-Chapelle could be seen burning, only 3 miles away.

Winton nevertheless succeeded, thanks to the guarantees he had obtained from the British. After the first train, things went relatively well crossing the Netherlands. Also active in saving Jewish children – some 10,000, mostly from Vienna and Berlin and mostly also via the Hook – was the Dutchwoman Gertruida Wijsmuller-Meier, so the plight of Jewish children was well known in the Netherlands. It is not known whether Winton and ‘Tante Truus’ (auntie Truus), as she was commonly known, ever met. In 2012 a statue was erected on the quay at the Hook to commemorate all those who saved Jewish children.

Winton found homes for 669 children, many of whose parents perished in Auschwitz.[12] Winton’s mother also worked with him to place the children in homes, and later hostels. Throughout the summer he placed advertisements seeking families to take them in. The last group of 250, which was intended to leave Prague on 1 September 1939 did not reach safety; the Nazis had invaded Poland, marking the start of World War II,and the children later perished in the concentration camps.

He said:

Since his story was taken up by the world’s media many years ago — and given a major boost by his 2003 knighthood — he feels it has all got “out of control” and that he can no longer correct oft-repeated misconceptions. Recently we were sitting in his house near Maidenhead when he pointed to the latest in a long line of honours and awards that have been heaped upon him. It was a framed certificate from a Jewish organisation in America citing his heroism for saving Jewish children during the war. “It’s got three mistakes in one sentence,” he remarked with a weary sigh. “I wasn’t heroic, the children weren’t all Jewish and it happened before the war.”

* “I found out that the children of refugees and other groups of people who were enemies of Hitler weren’t being looked after. I decided to try to get permits to Britain for them. I found out that the conditions which were laid down for bringing in a child were chiefly that you had a family that was willing and able to look after the child, and £50, which was quite a large sum of money in those days, that was to be deposited at the Home Office. The situation was heartbreaking. Many of the refugees hadn’t the price of a meal. Some of the mothers tried desperately to get money to buy food for themselves and their children. The parents desperately wanted at least to get their children to safety when they couldn’t manage to get visas for the whole family. I began to realize what suffering there is when armies start to march.”

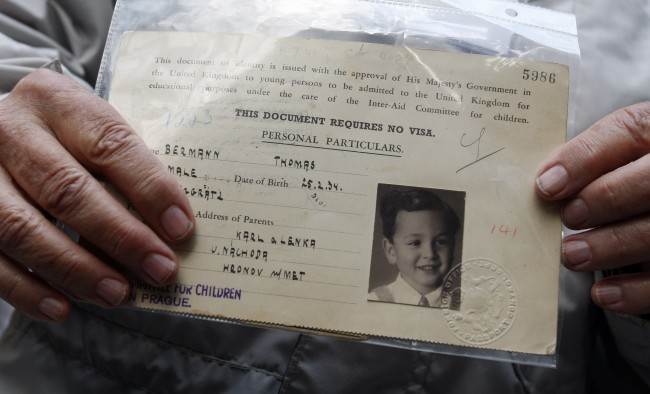

Thomas Bermann one of the original rescued children shows his papers.

A statue to him stands in Prague:

Nicholas Winton receiving a letter of thanks from the Prime Minister. He became a Knights Batchelor in the New Year’s Honours List 11/03/03.

This video is the BBC’s That’s Life aired in 1988.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.