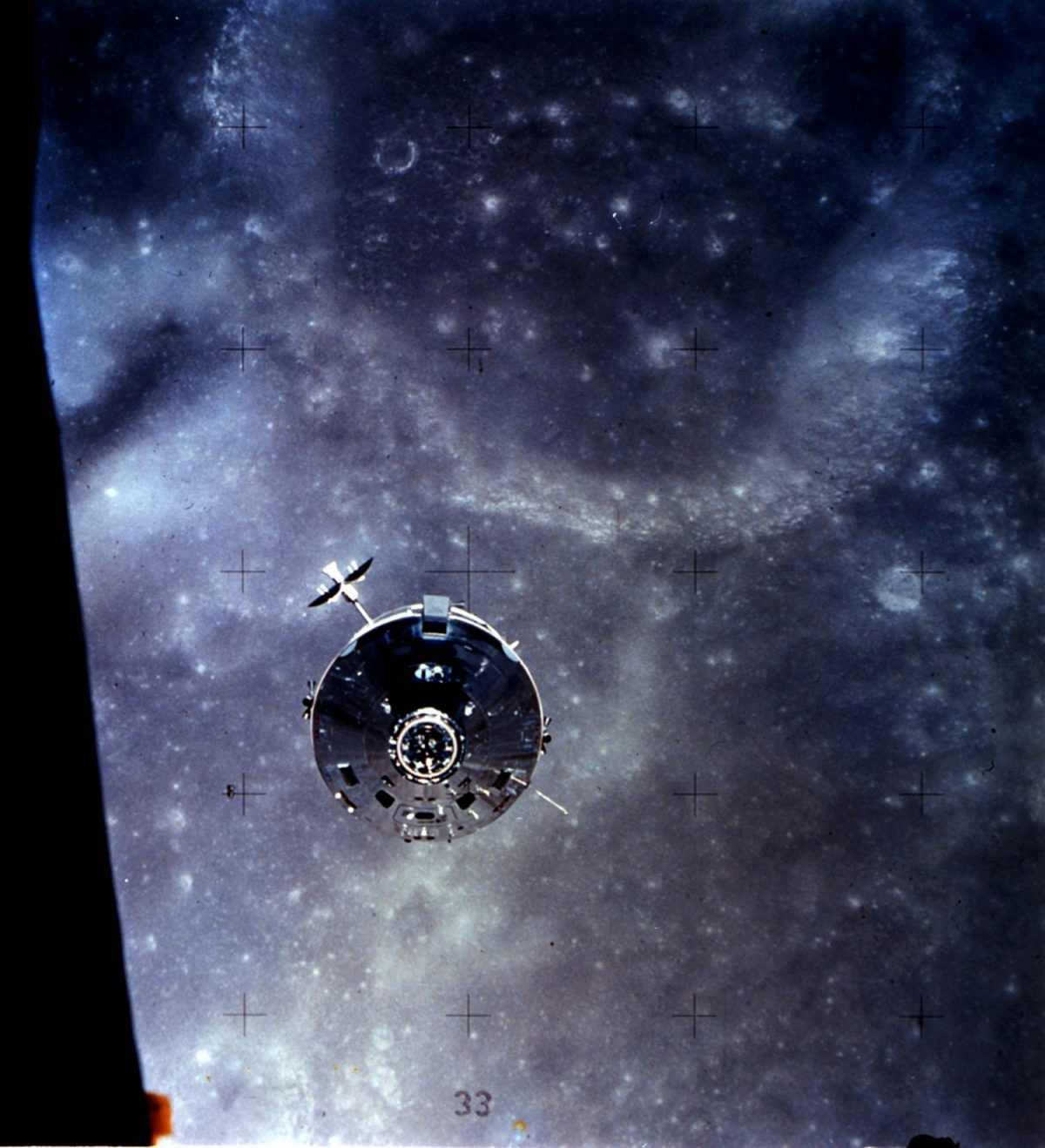

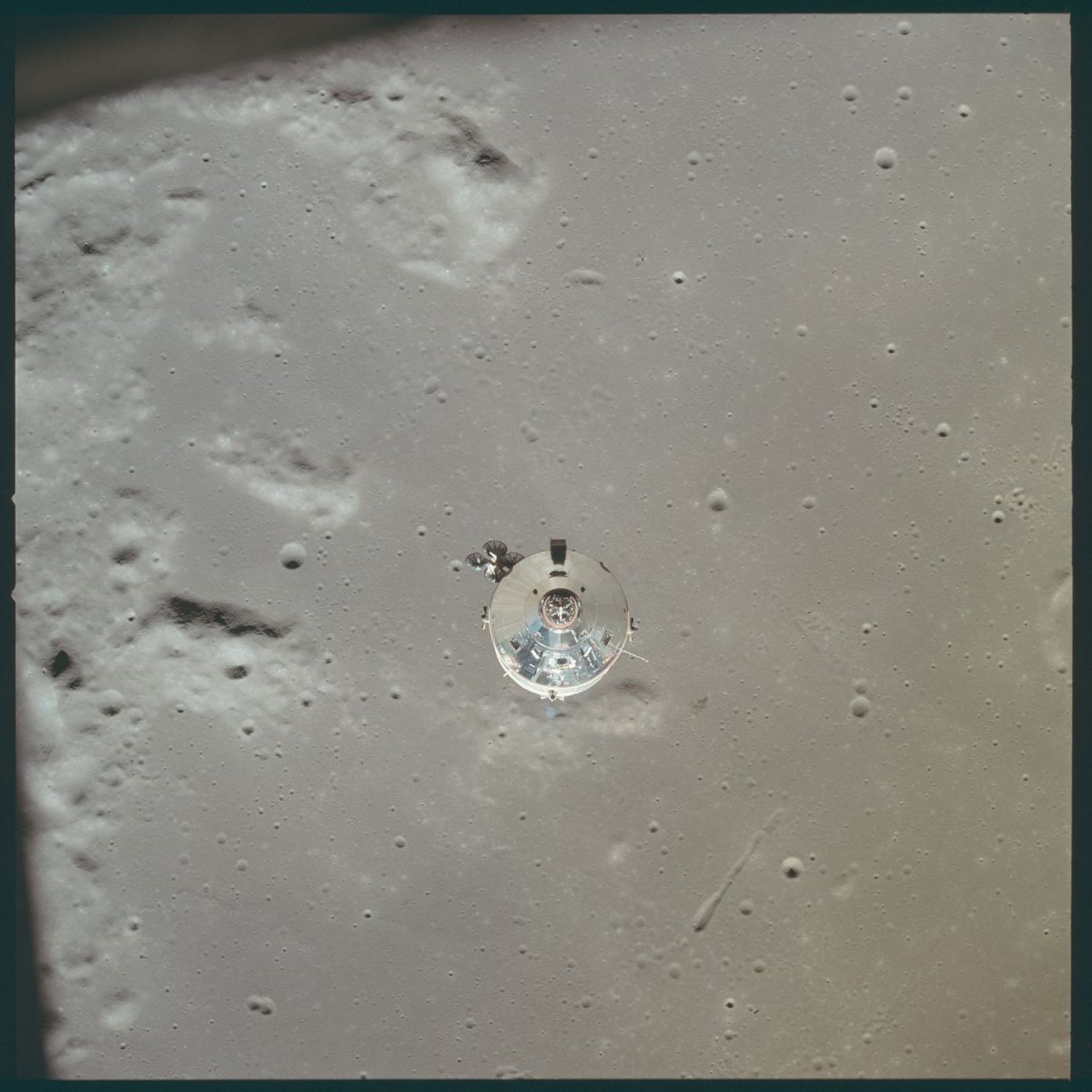

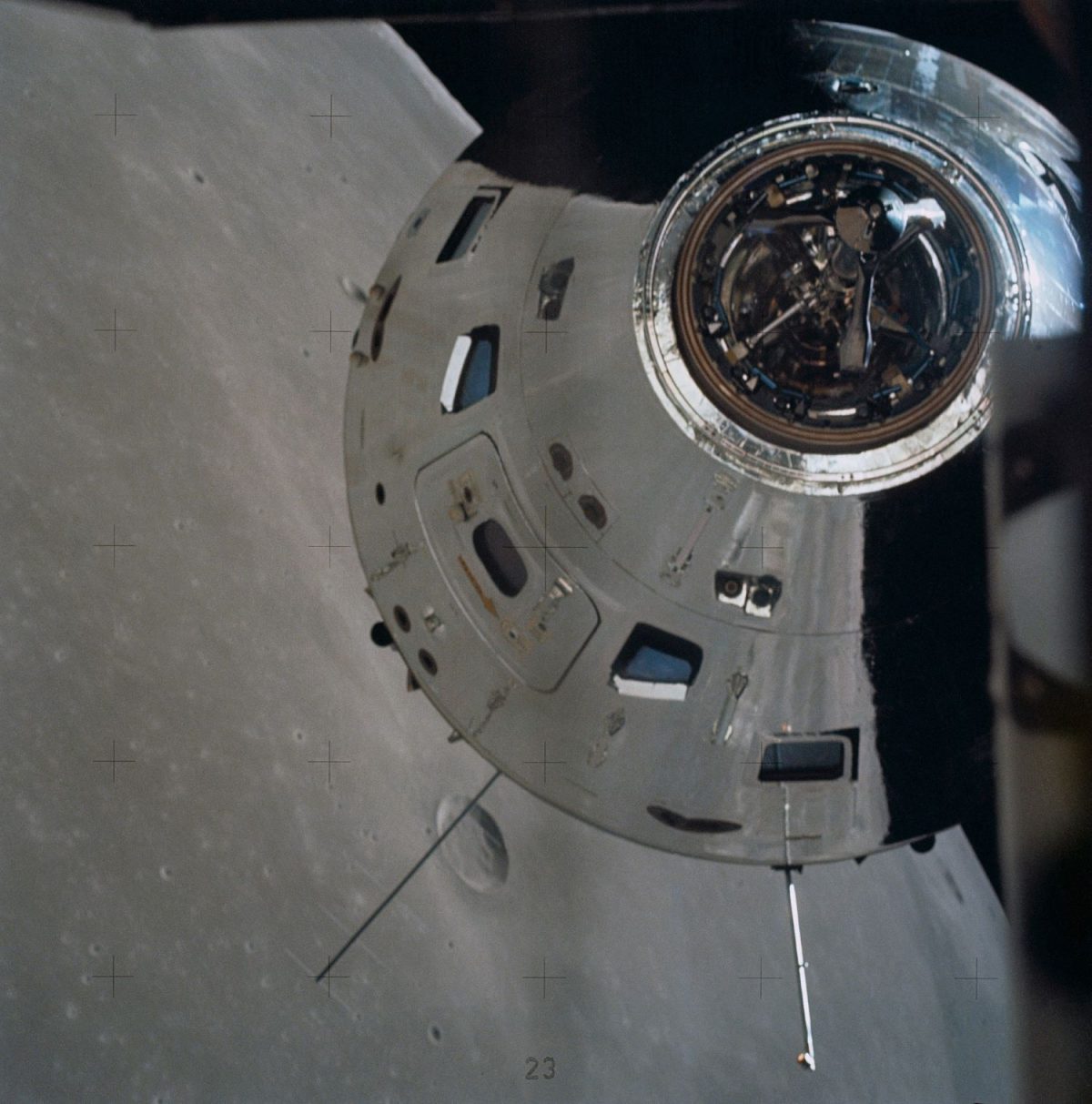

In this photo, the Apollo 16 Command and Service Module (CSM) “Casper” approaches the Lunar Module (LM). The two spacecraft were about to make their final rendezvous of the mission, on April 23, 1972. Astronauts John W. Young and Charles M. Duke Jr., aboard the LM, were returning to the CSM in lunar orbit after three successful days on the lunar surface. Astronaut Thomas K. Mattingly II was in the CSM.

The Apollo Mission astronauts came in packs of three. Most know the names of at least two of these astronauts – generally the pair who first set foot on the moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin. But we often forget the name of the third astronaut, the one who spent his time orbiting the moon in the Command Module.

On the Apollo 11 mission, Michael Collins was the third astronaut. He was the designated driver. The one who had to ensure the Command Module Columbia was able to connect with Armstrong and Aldrin in Lunar Module Eagle and return the crew to Earth. Collins feared if anything went wrong and his fellow astronauts were left on the moon he would be “a marked man for life”. As he said:

“I would have been that guy who left them up there on the moon to die. It would have been an awful, terrible, national catastrophe.”

Collins spent 21 hours in Columbia orbiting the Moon. For 48-minutes he was out of radio contact as he orbited the dark side of the moon where he was further removed from the rest of humanity than anyone before him. His sense of isolation was reinforced:

.”..by the fact that radio contact with the Earth abruptly cuts off at the instant I disappear behind the moon, I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it. If a count were taken, the score would be three-billion-plus-two over on the other side of the moon, and one-plus-God-knows-what on this side.”

Collins orbited the moon 30-times at a height of 69 miles above the surface where Armstrong and Aldrin explored the ground. Among the strange things astronauts have left on the Moon include a family photograph, two golf balls, and a miniature statue to all the astronauts and cosmonauts who died attempting to reach or circle the rock.

Like all the other Apollo mission astronauts, Collins photographed the moon, the Earth and the Apollo spacecraft. These photographs are among those most astounding images ever to be captured on film.

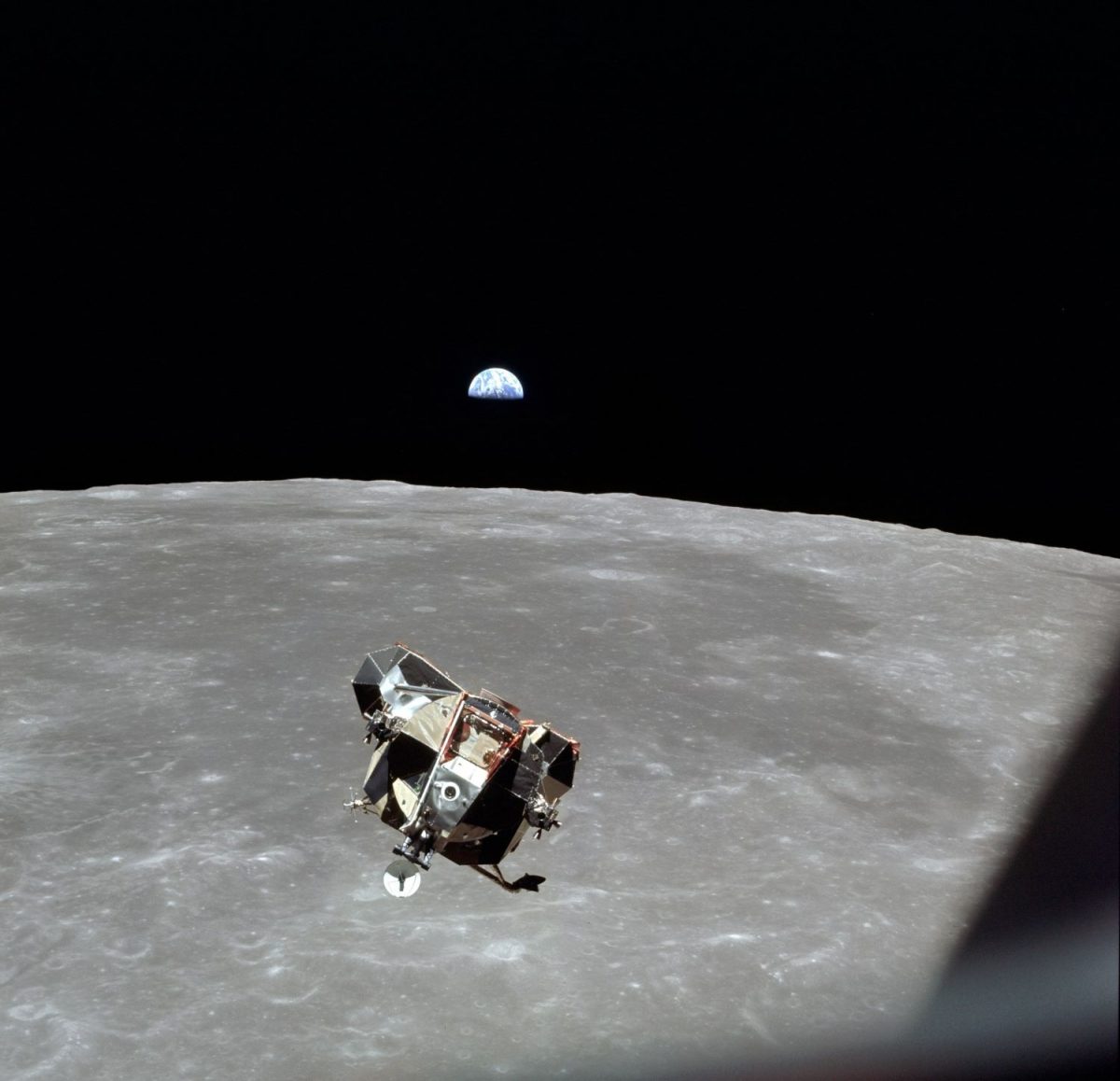

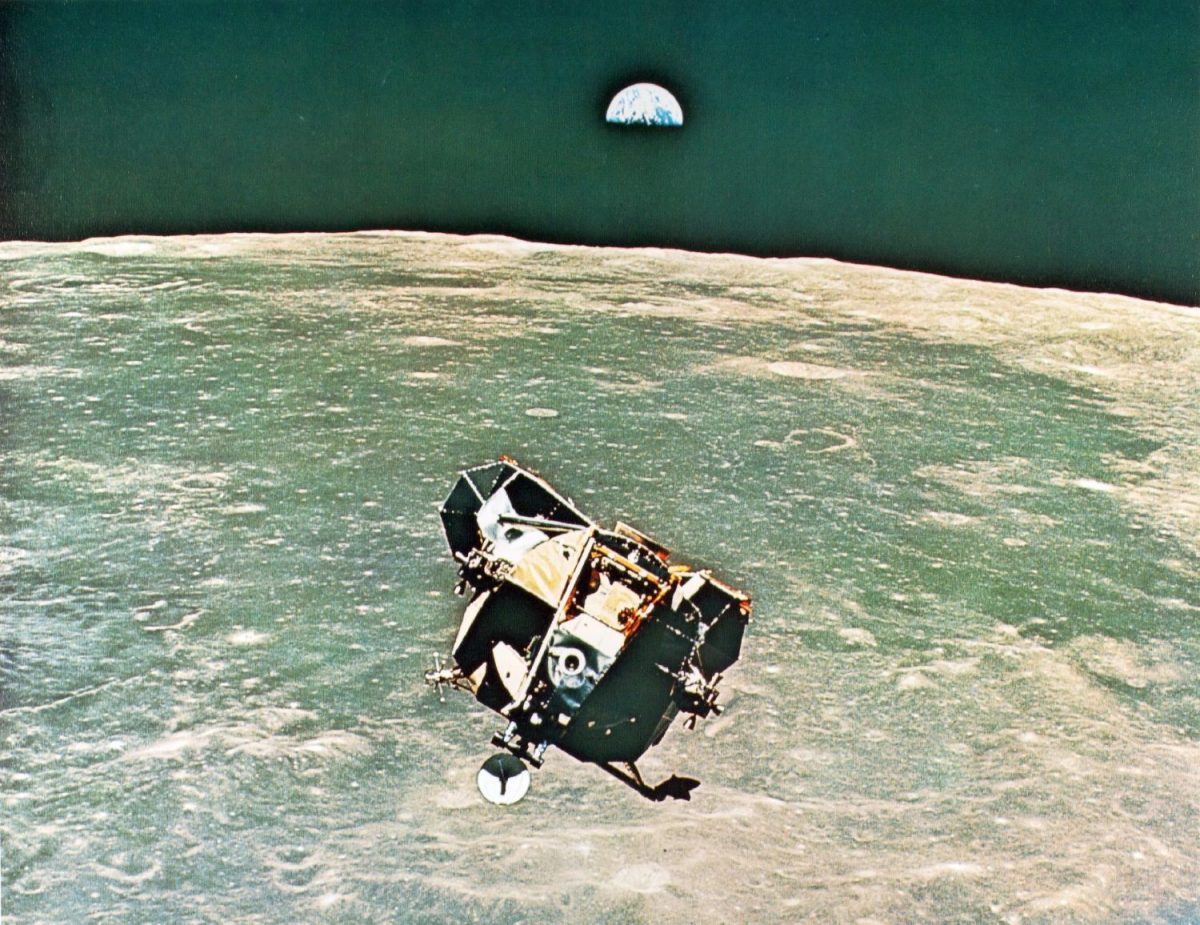

The Apollo 11 lunar module, the Moon, and the Earth, 21st July 1969.

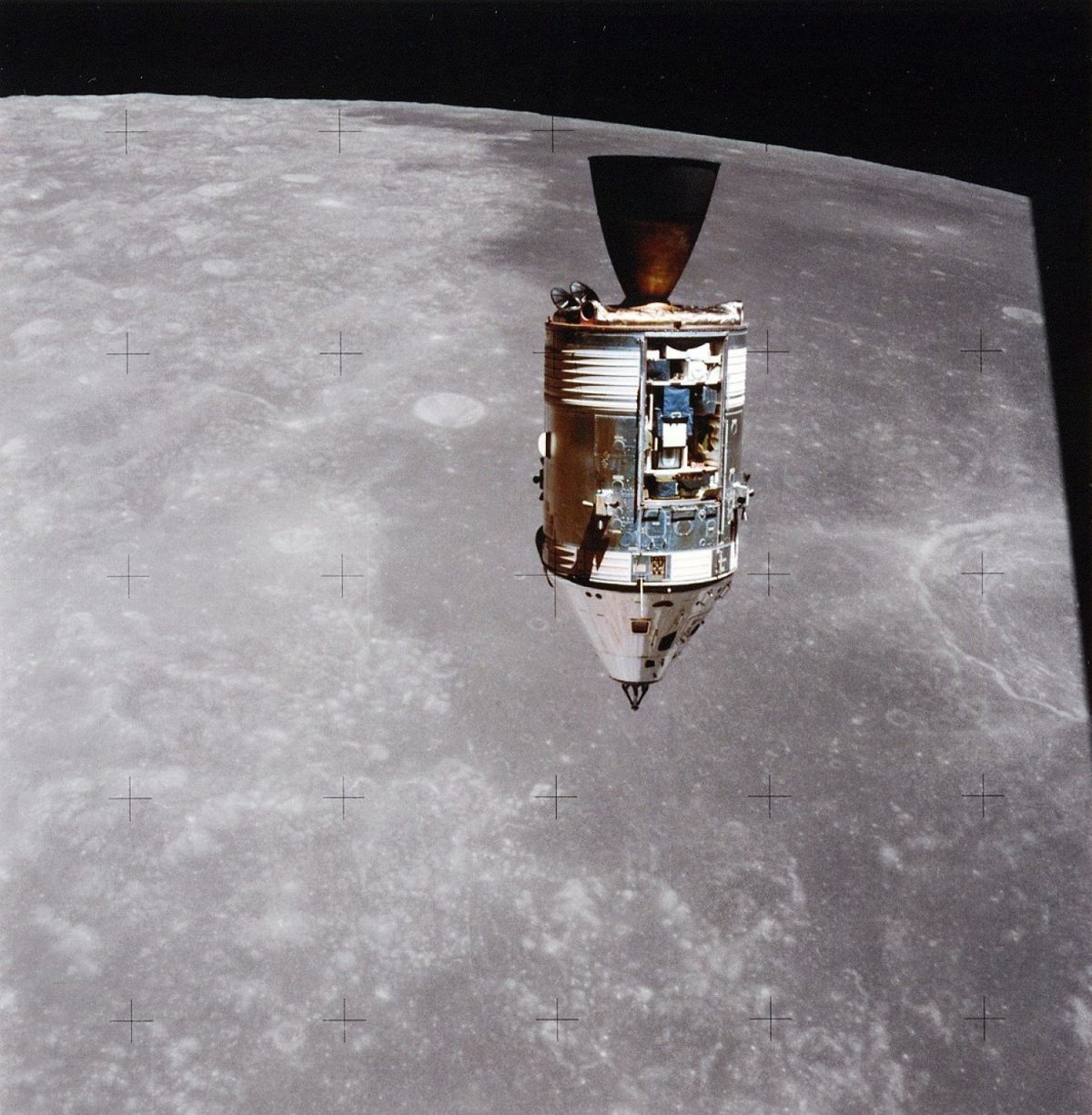

Apollo 15’s Command/Service Module Endeavour as seen by from the Lunar Module Falcon, during rendezvous.

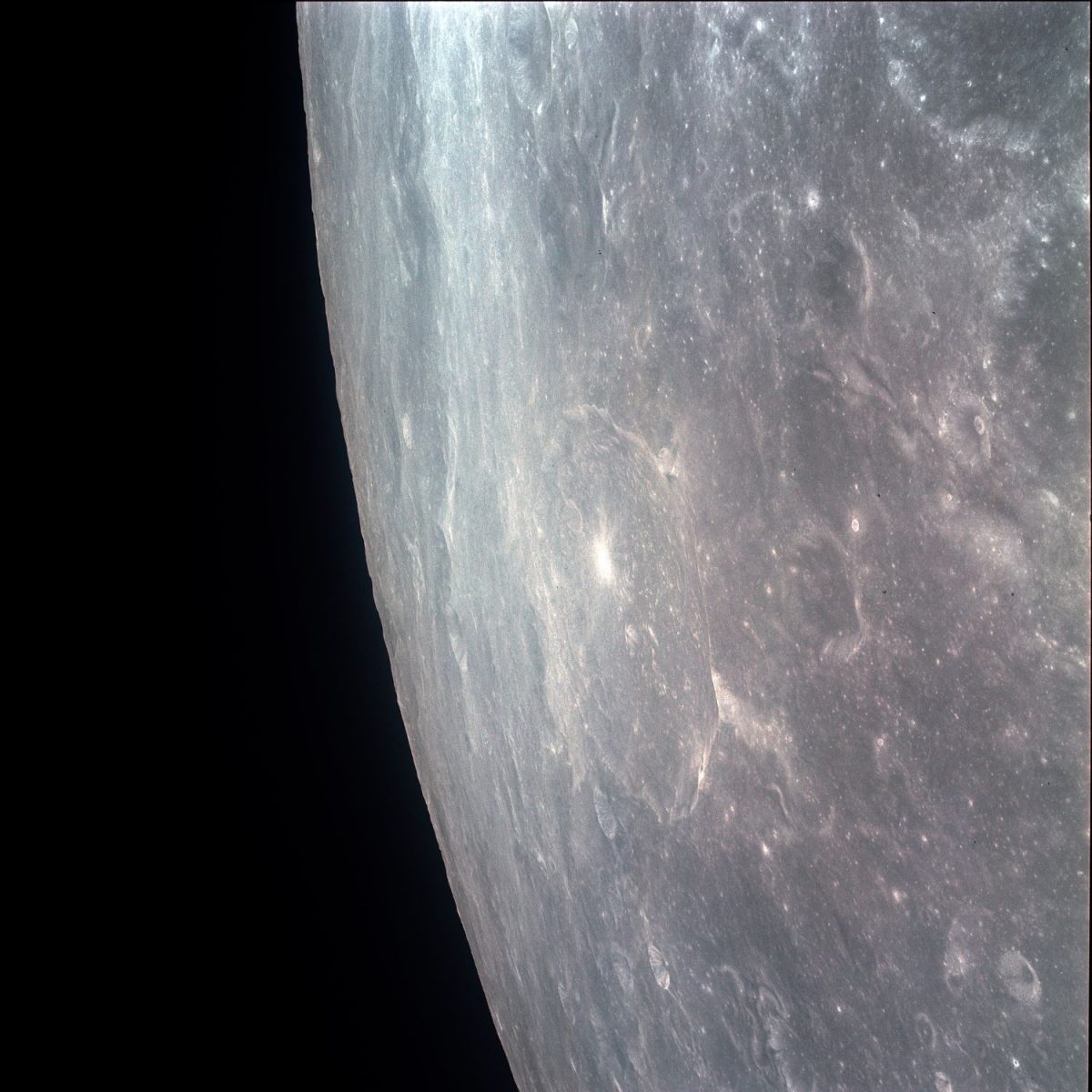

Apollo 8 Picture of the Moon, December 1968.

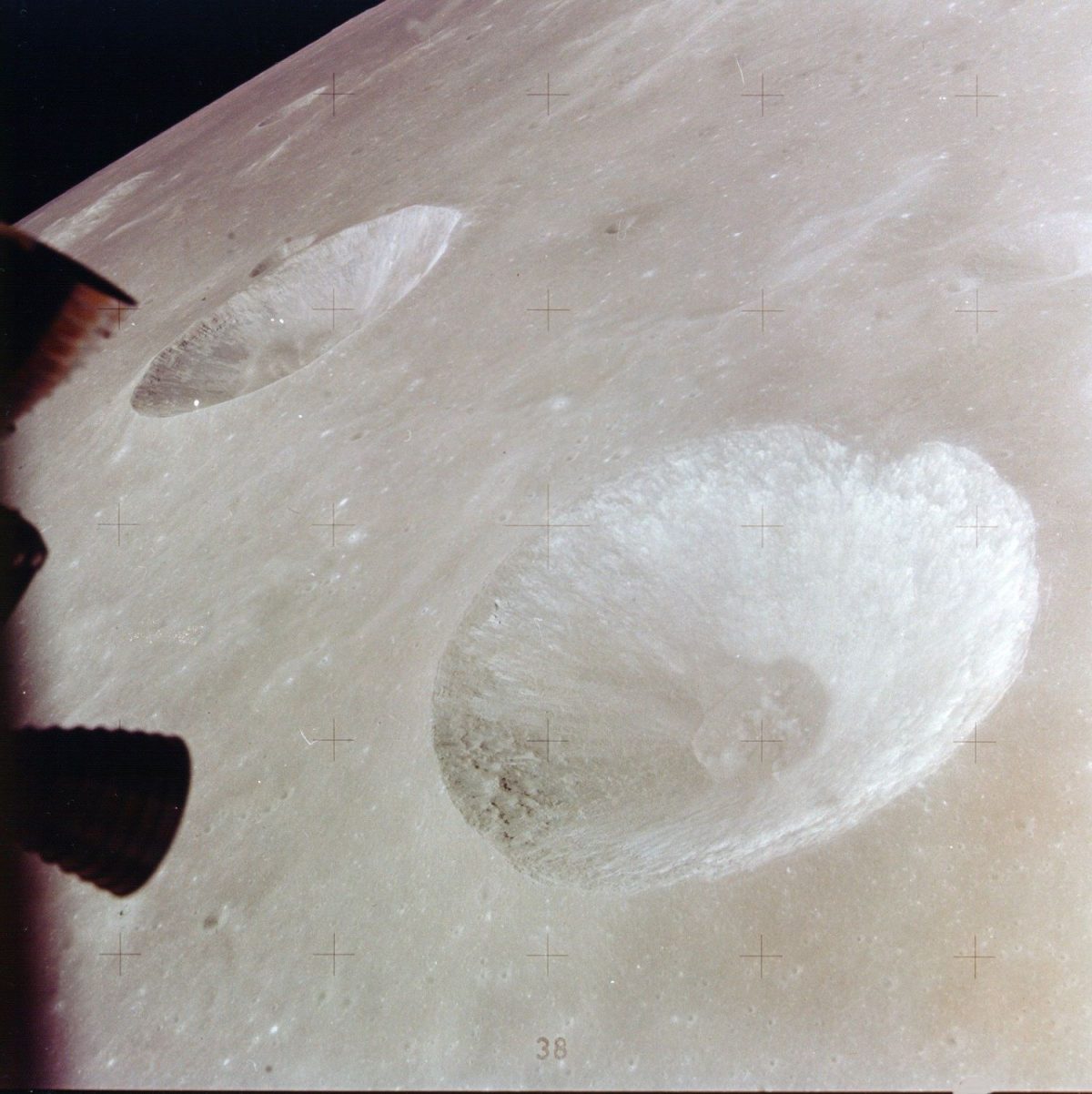

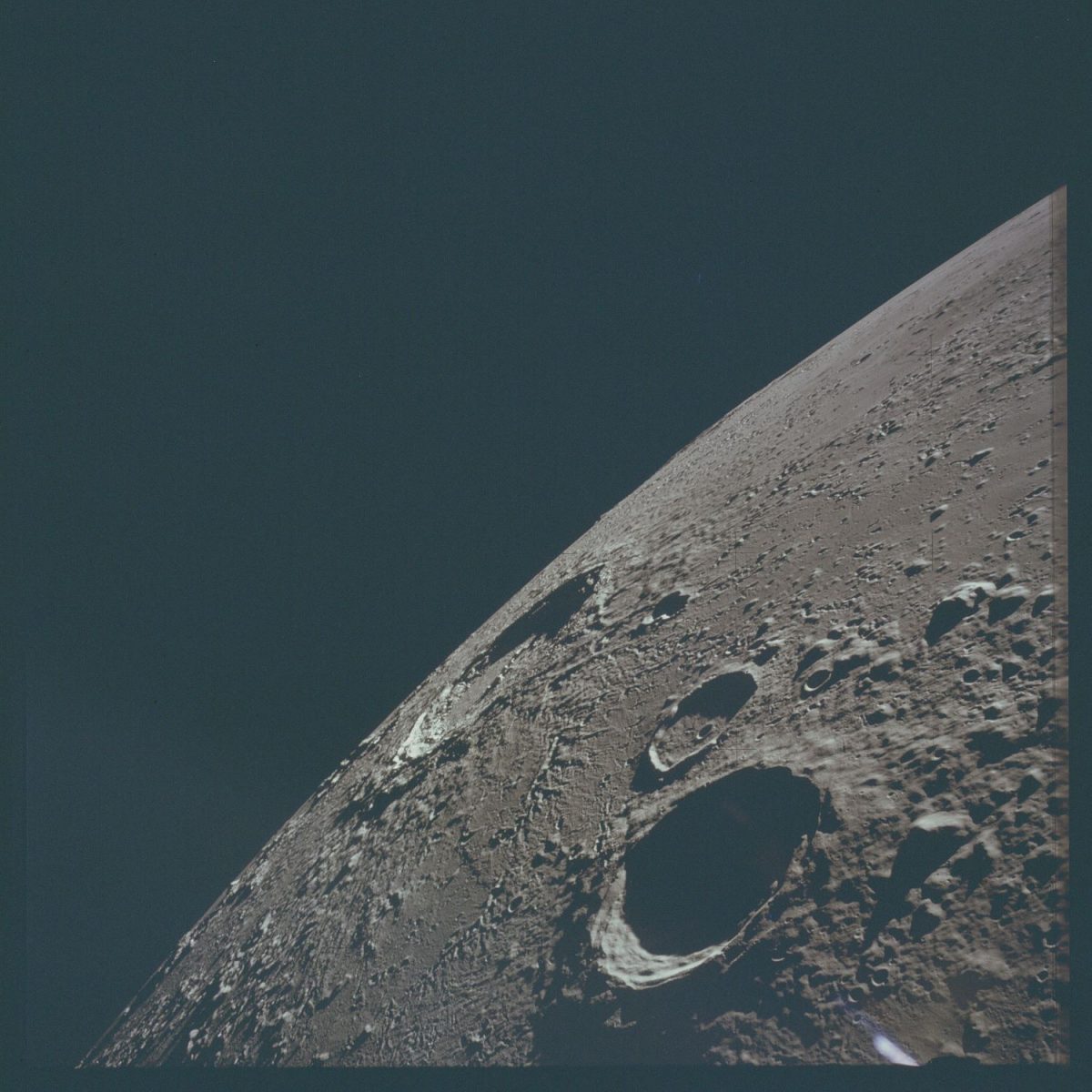

Apollo 15 view of Moon’s craters Carmichael and Hill.

Apollo 11 rendezvous.

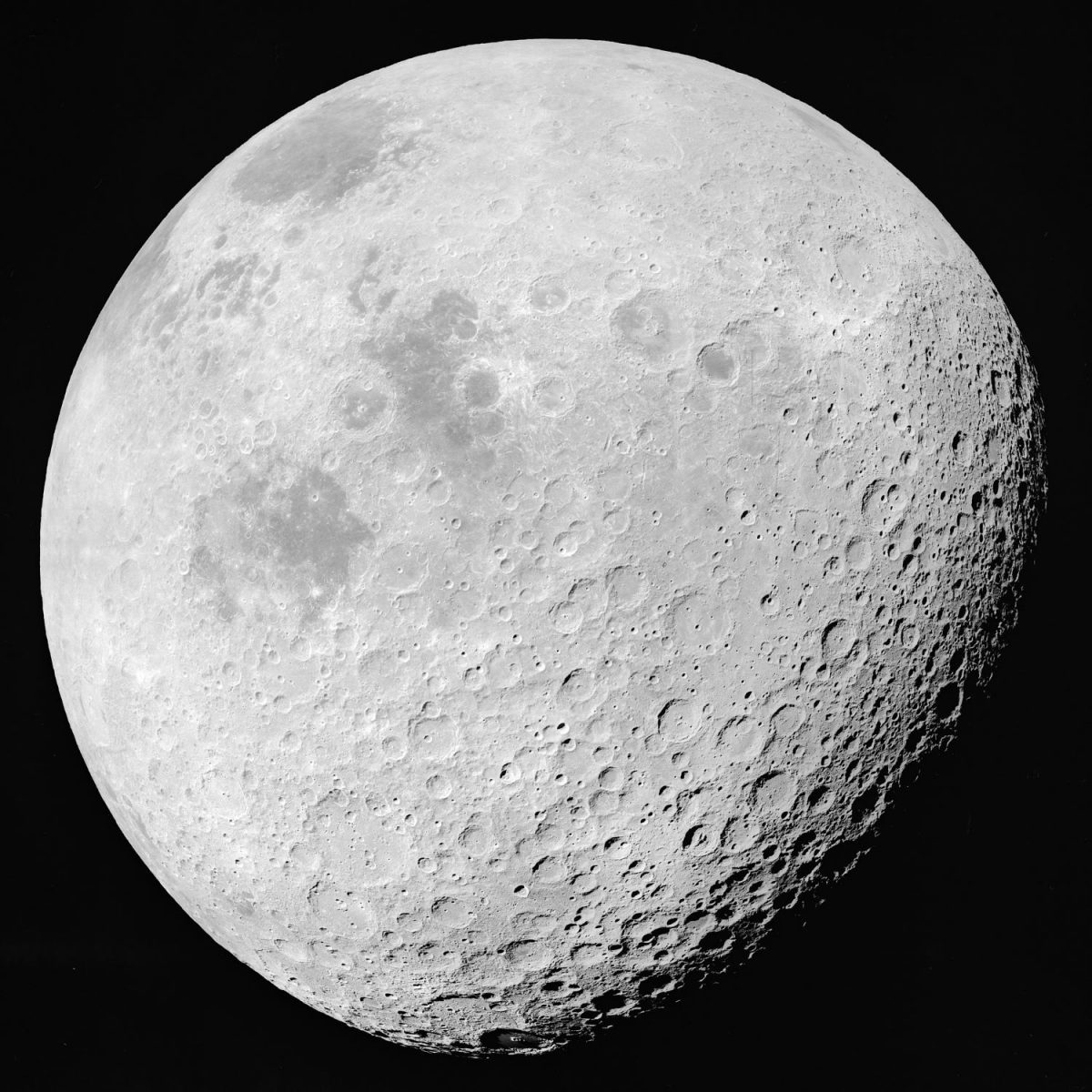

Photograph of the Moon taken by the Apollo 11 crew during their trans-lunar-coast, July 1969.

Apollo 11 Hasselblad image from film magazine 37/R – Orbit, Post-Landing, Post-EVA, 1969.

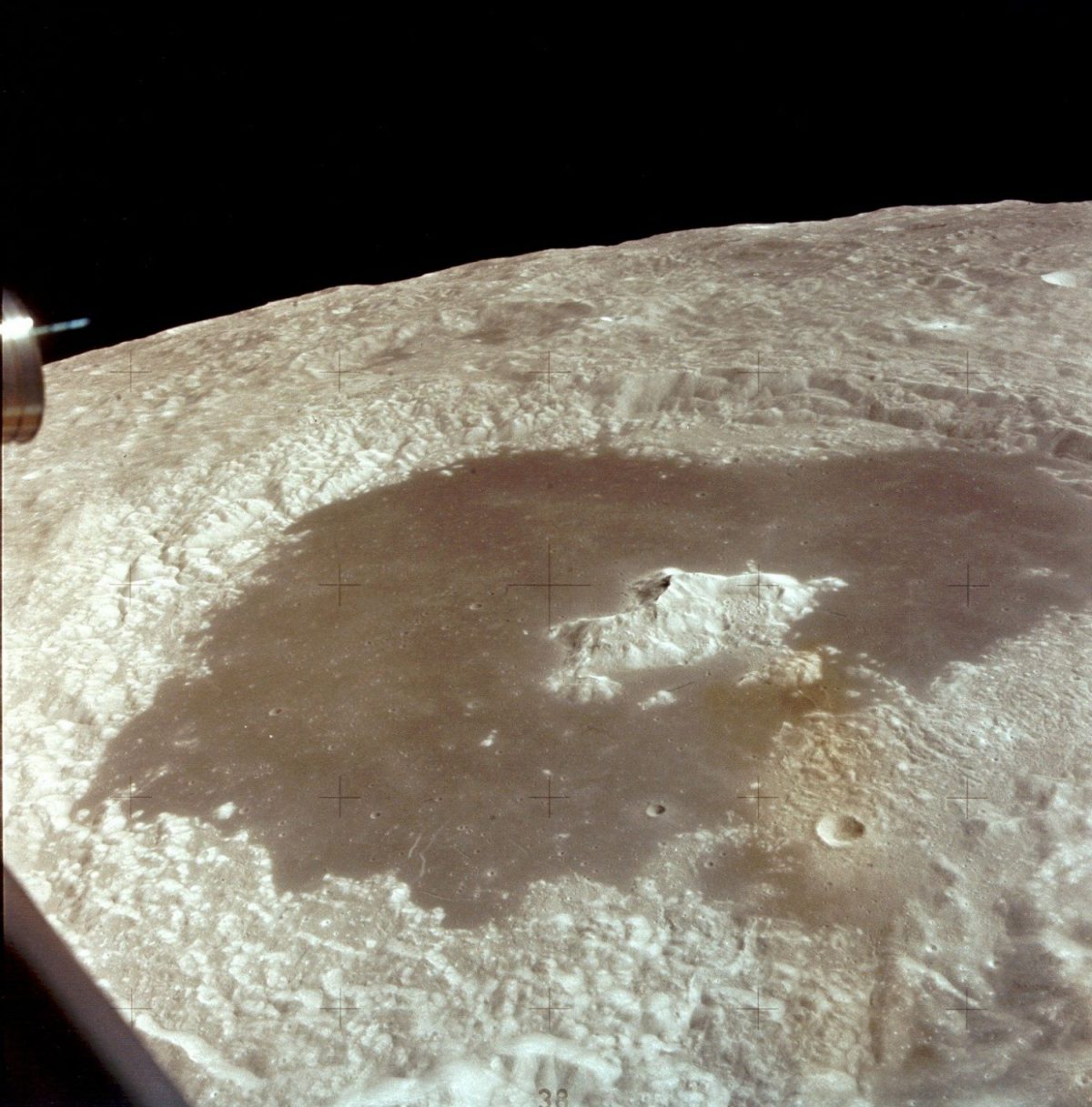

Aristarchus Crater from Apollo 15.

The Apollo 12 lunar module Intrepid prior to descent, on November 19, 1969. The coordinates of the center of the lunar surface shown in picture are 4.5°W longitude and 7°S latitude. The view is towards the west and slightly north. The small distinct crater in the bottom left area is Ammonius; it is located within the huge Ptolemaeus crater, which is hard to distinguish here but consists of the smooth area which takes up much of the bottom left of the image, and whose partial wall can be seen to the right of Ammonius. The large crater at the right-hand side about halfway between top and bottom is Herschel. Just above it is the small Herschel C. Further up and to the right, near the right edge of the image, is Mösting A, which appears bright here. The smaller crater just to the left of a line between Herschel C and Mösting A is Flammarion B. Near the horizon and diagonally right and down from the lunar module is Lalande crater; diagonally left and down from the lunar module is the somewhat smaller Lalande A. Further towards the foreground and slightly to the left of Lalande is the smaller Lalande C.

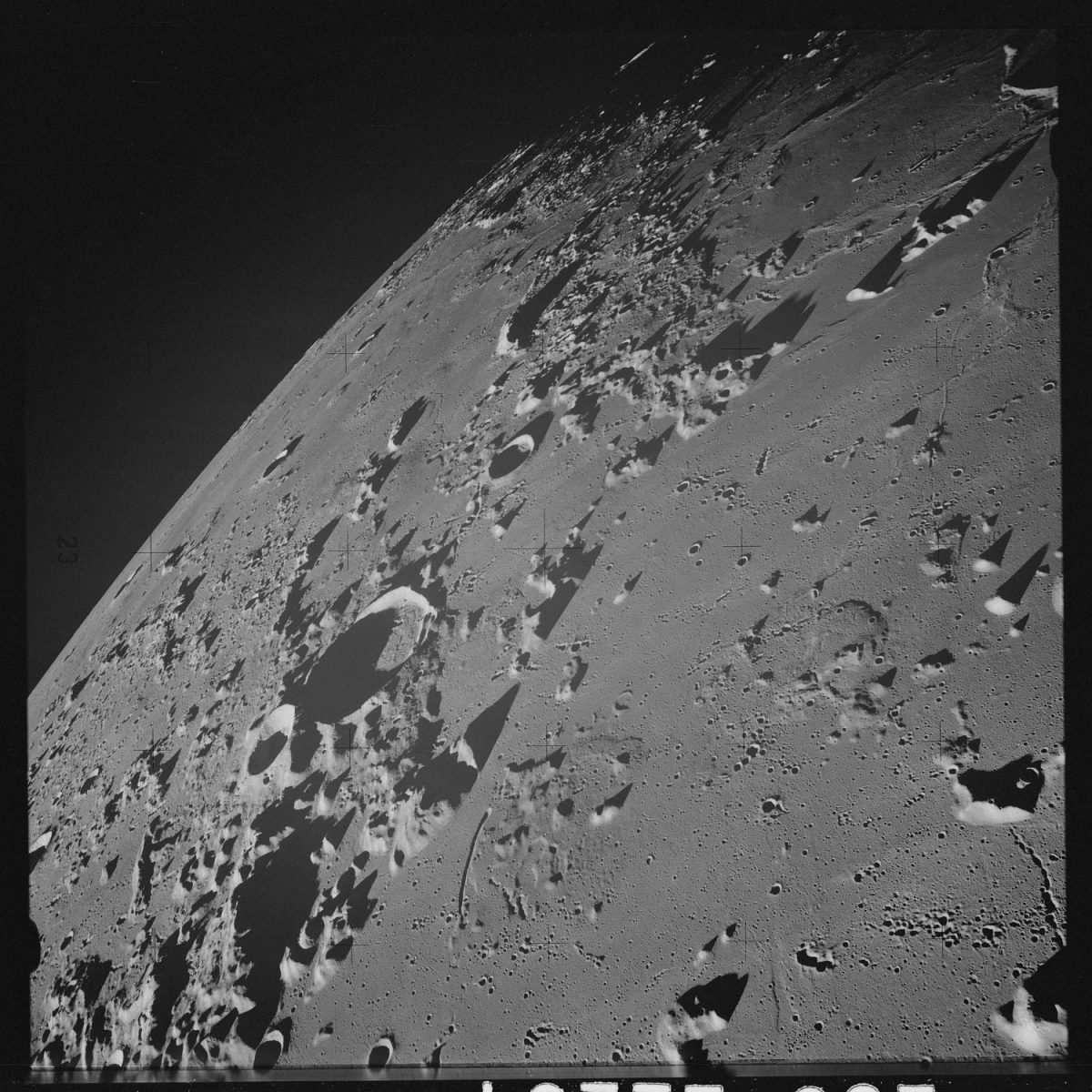

From Apollo 12; A high-oblique view looking northeast. This photograph was taken from the LM. The large crater Copernicus is in full view, and the Carpathian Mountain Range is visible on the horizon. The stark lunar relief is accented by the low Sun elevation angle.

The surface of the Moon from Apollo 17.

This bright-rayed crater, Giordano Bruno, on the lunar farside was photographed from the Apollo 13 spacecraft during its pass around the moon. This area is northeast of Mare Marginus. The bright-rayed crater is located at about 105 degrees east longitude and 45 degrees north latitude. The crater Joliot-Curie is located between Mare Marginus and the rayed crater. This view is looking generally toward the northeast, April 1970.

This oblique view of the Moon’s surface was photographed by the Apollo 10 astronauts in May of 1969. Center point coordinates are located at 13 degrees, 3 minutes east longitude and 7 degrees, 1 minute north latitude. One of the Apollo 10 astronauts attached a 250mm lens and aimed a handheld 70mm camera at the surface from lunar orbit for a series of pictures in this area.

Tsiolkovsky Crater from the Lunar Module, Apollo 15.

Earthrise as seen by the crew of Apollo 15.

View of Moon. Oblique towards Tranquility Base, part coverage of Target of Opportunity (TO) 115. TO 115 is Craters Hypatia and Alfraganus A, and chain of shallow sharp depressions East of Alfraganus. Image taken from inside the Lunar Module (LM) from orbital altitude over the moon during the Apollo 11 Mission, July 1969.

The surface of the moon is reflected in the command and service module as it prepares to rendezvous with the lunar module in this December 1972 image from the Apollo 17 mission.

Earthrise from Apollo 10.

The moon as seen from the depaturing Apollo 16.

H/T NASA Wikipedia.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.