What are we looking at?

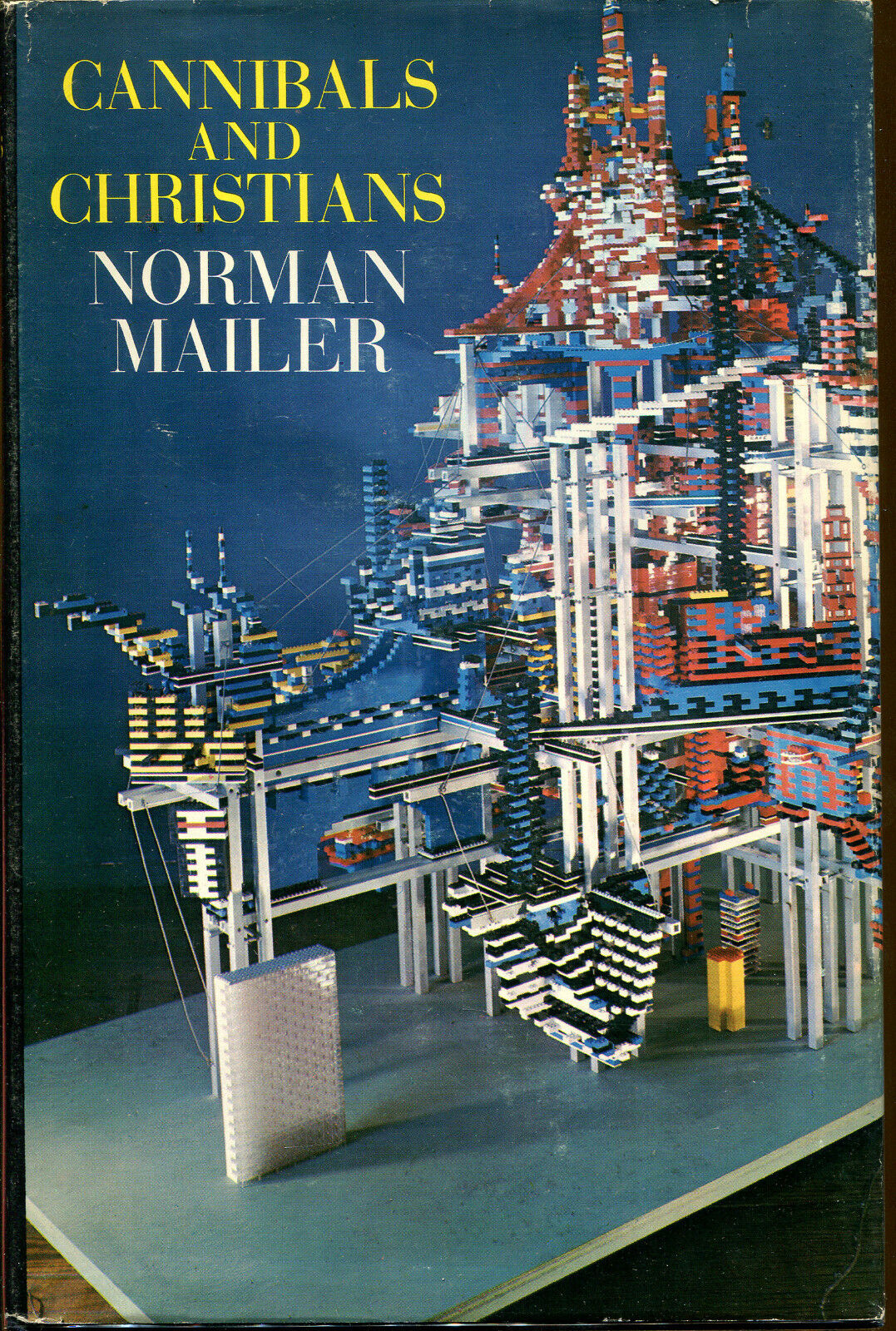

Norman Mailer’s collected volume of essays, journalism, fiction and self-interviews Cannibals and Christians, which arrived in bookshops on October 1st 1966.

Who’s Norman Mailer?

Norman Kingsley Mailer (1923-2007) was one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century.

Really?

Yes.

What did he write?

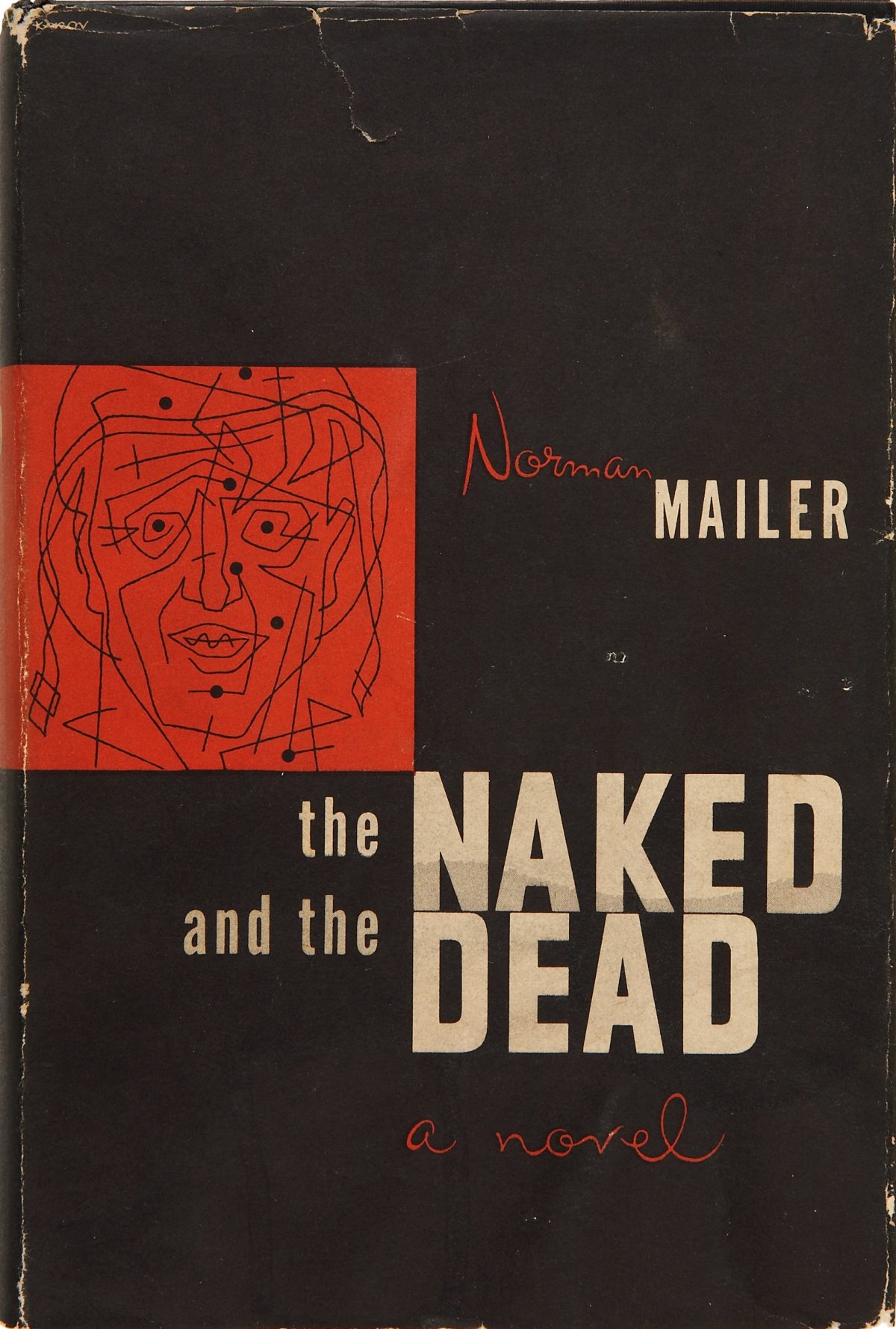

His first book The Naked and the Dead was published when he was 25. It’s a large interconnected tale centred around a group of soldiers fighting in the Philippines. It’s loosely based on Mailer’s own experiences serving with the 112th Cavalry Regiment during the Second World War. The Naked and the Dead was highly praised by George Orwell and has been described as the greatest novel written about the Second World War.

Naked and the Dead, published in 1948

Not bad. What else?

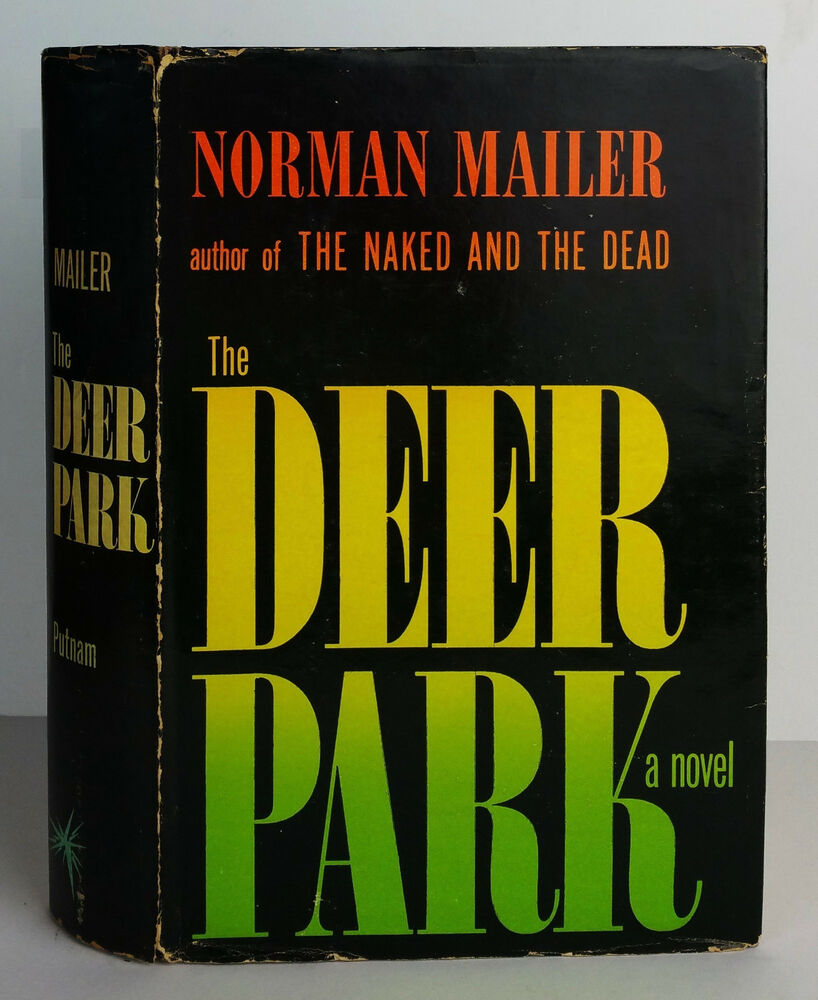

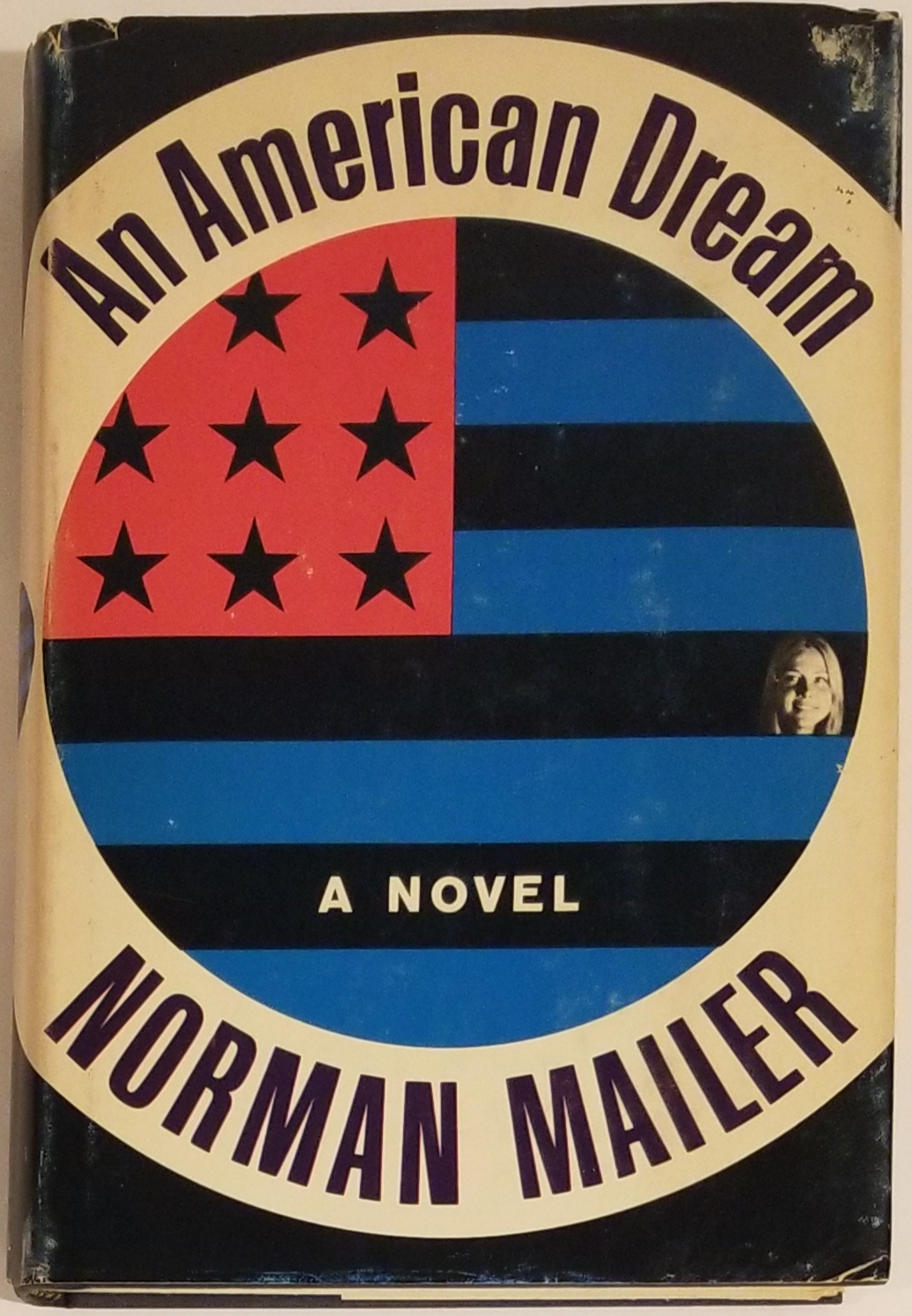

He wrote several best selling novels including The Deer Park (1955) about Hollywood; An American Dream (1965) a highly controversial existential thriller about a man who murders his ex-wife; Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967) a satire featuring two grotesque characters hunting bears–which in some respects pre-empts Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by four years; Ancient Evenings (1983) a massive and greatly misunderstood book about ritual, war, sex and death in ancient Egypt; Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1984) a gripping noir thriller that plays with many of Mailer’s philosophical ideas; Harlot’s Ghost (1991) a 1300-page chronicle on the C.I.A. which is arguably Mailer’s greatest book–though he never delivered the long promised second volume; The Gospel According to the Son (1997) about Jesus; and A Castle in the Forest (2007) about Hitler–a book far, far better than many critics thought.

He was one of the pioneers of New Journalism. Won the Pulitzer Prize twice. First for Armies of the Night in 1968, which recounted his adventures during the March on the Pentagon in 1967; and for The Executioner’s Song in 1979 which focussed on the life of double murderer Gary Gilmore and the events surrounding his execution by firing squad.

Mailer wrote several non-fiction books on Marilyn Monroe, Picasso, the Moon landings, a classic on the “Rumble in the Jungle” between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman–The Fight (1975), and a biography of Lee Harvey Oswald–Oswald’s Tale: An American Mystery (1995). If this wasn’t enough, Mailer wrote millions of words of journalism, plays, poetry, and screenplays. By any literary standard he produced an enormous and hugely influential body of work during his lifetime.

The Deer Park, published in 1955

An American Dream (1965)

You’re a fan?

Oh, yeah…

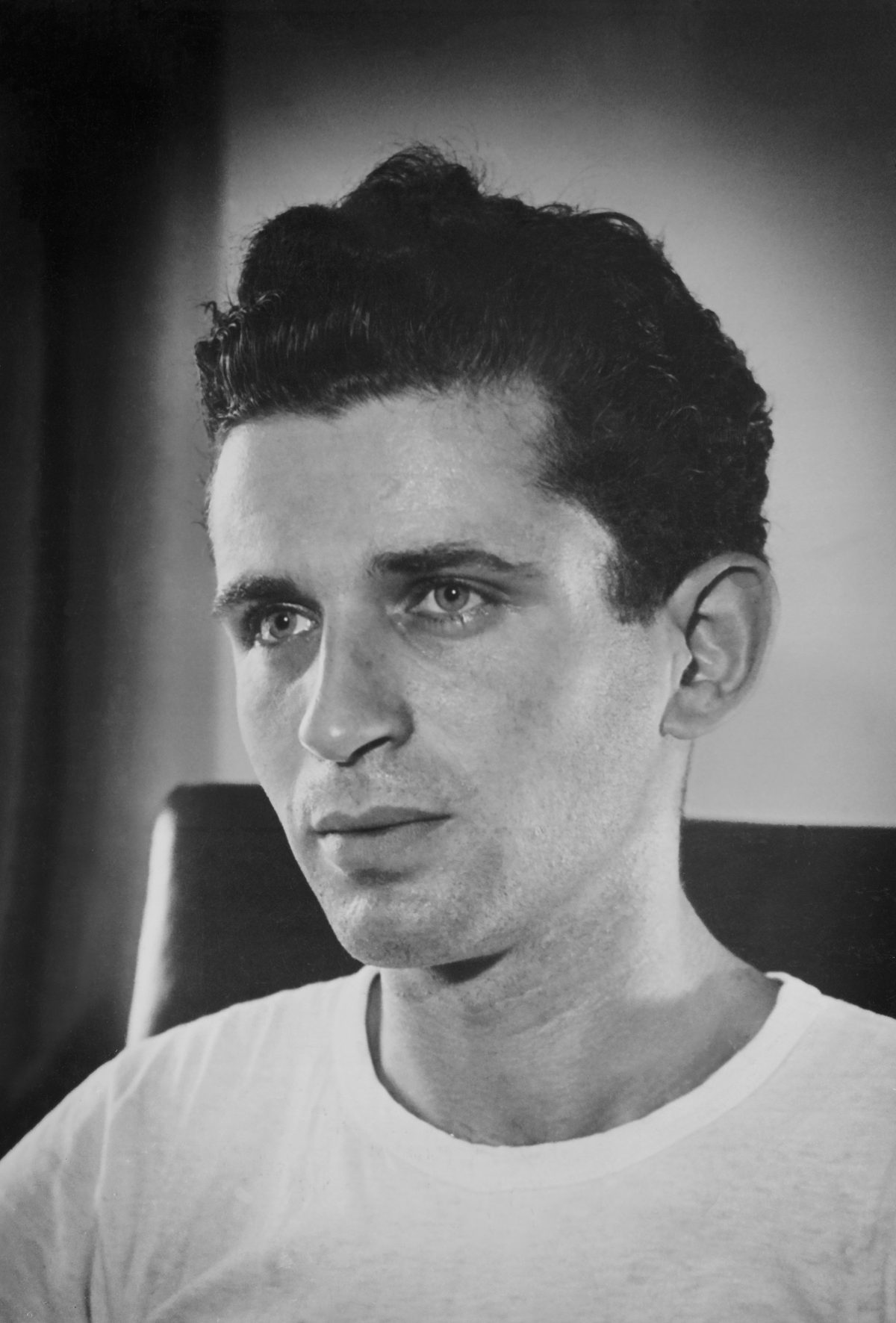

Portrait of the author as a young man, 1948

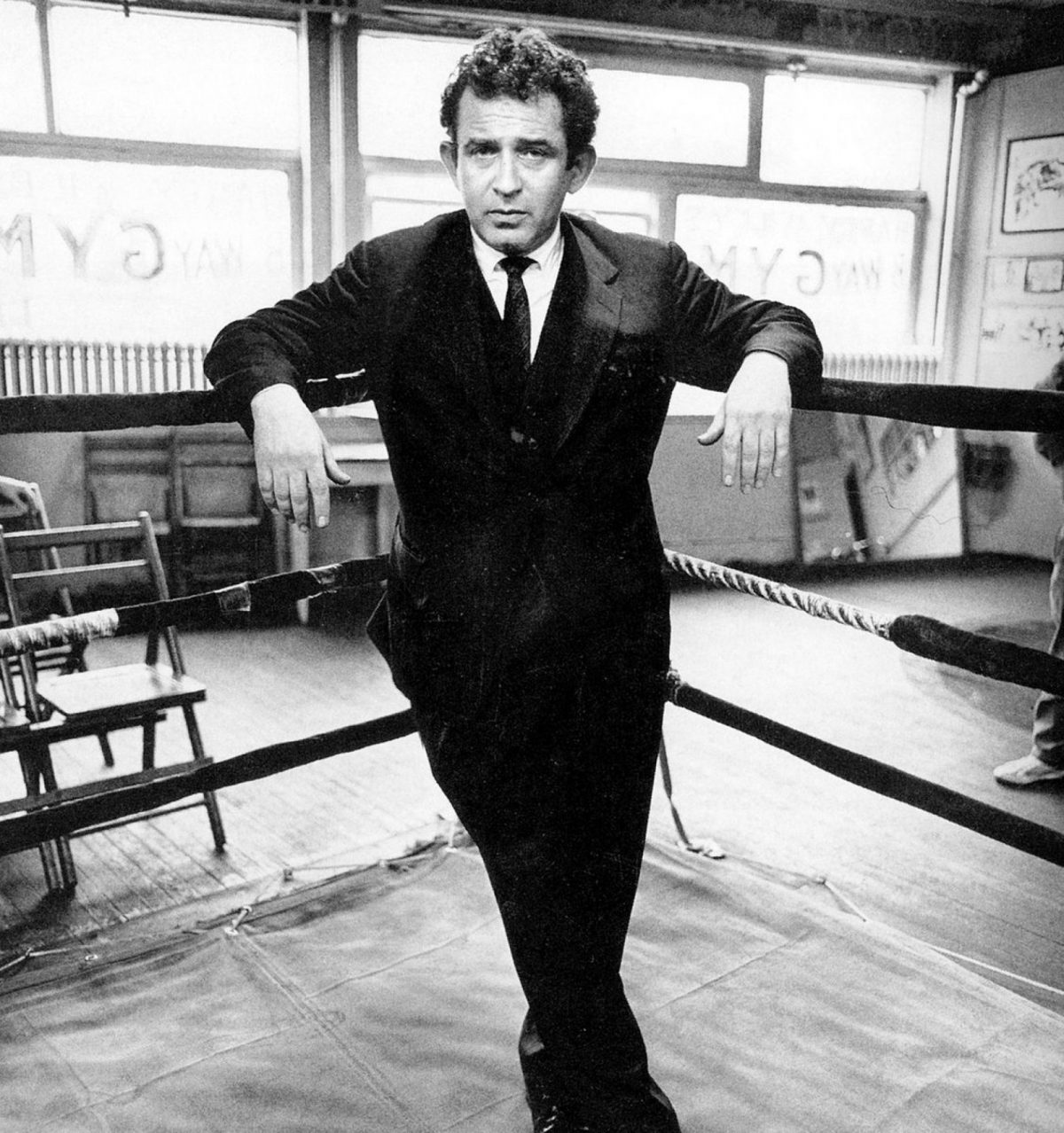

Norman Mailer

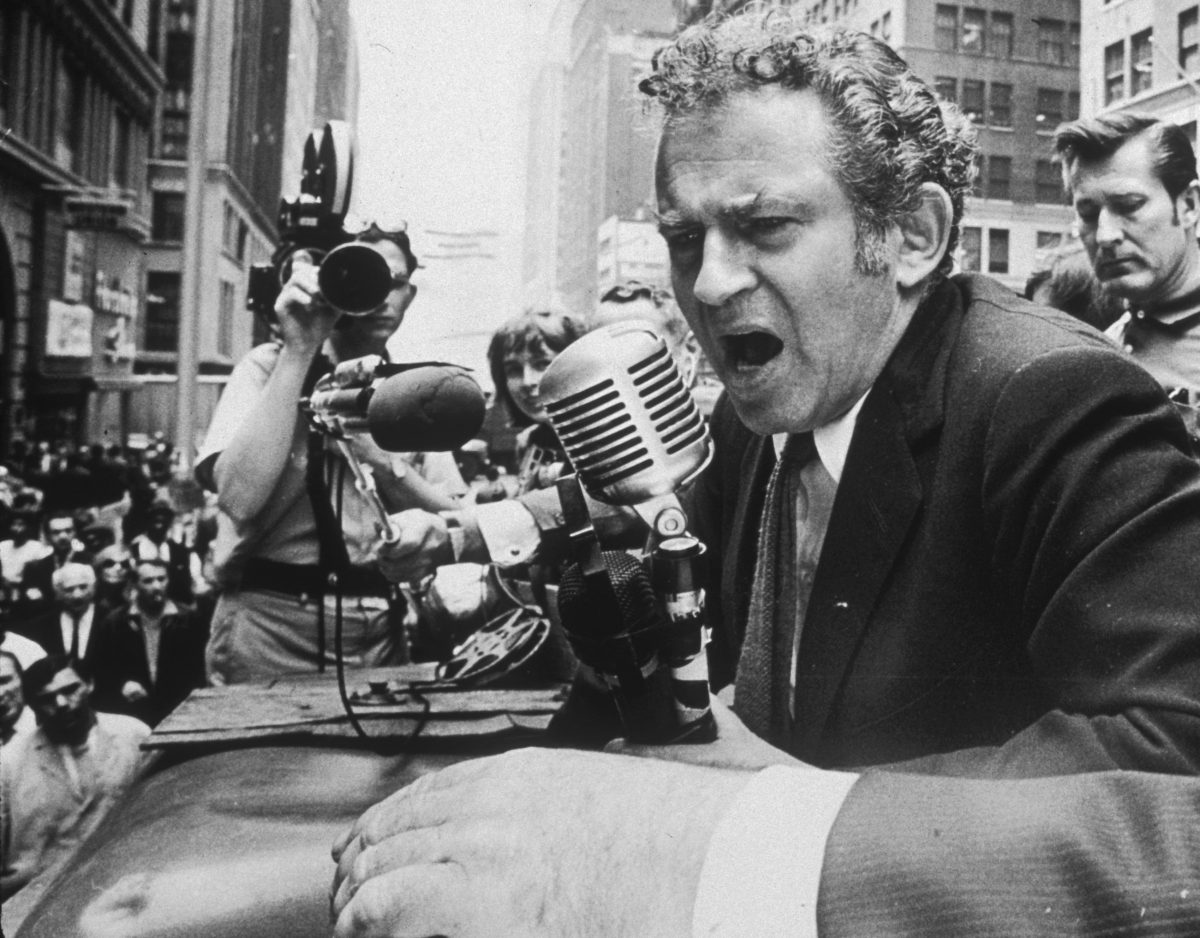

Norman Mailer campaigning for Mayor of New York City in 1969. (Bob Peterson)

And the cover?

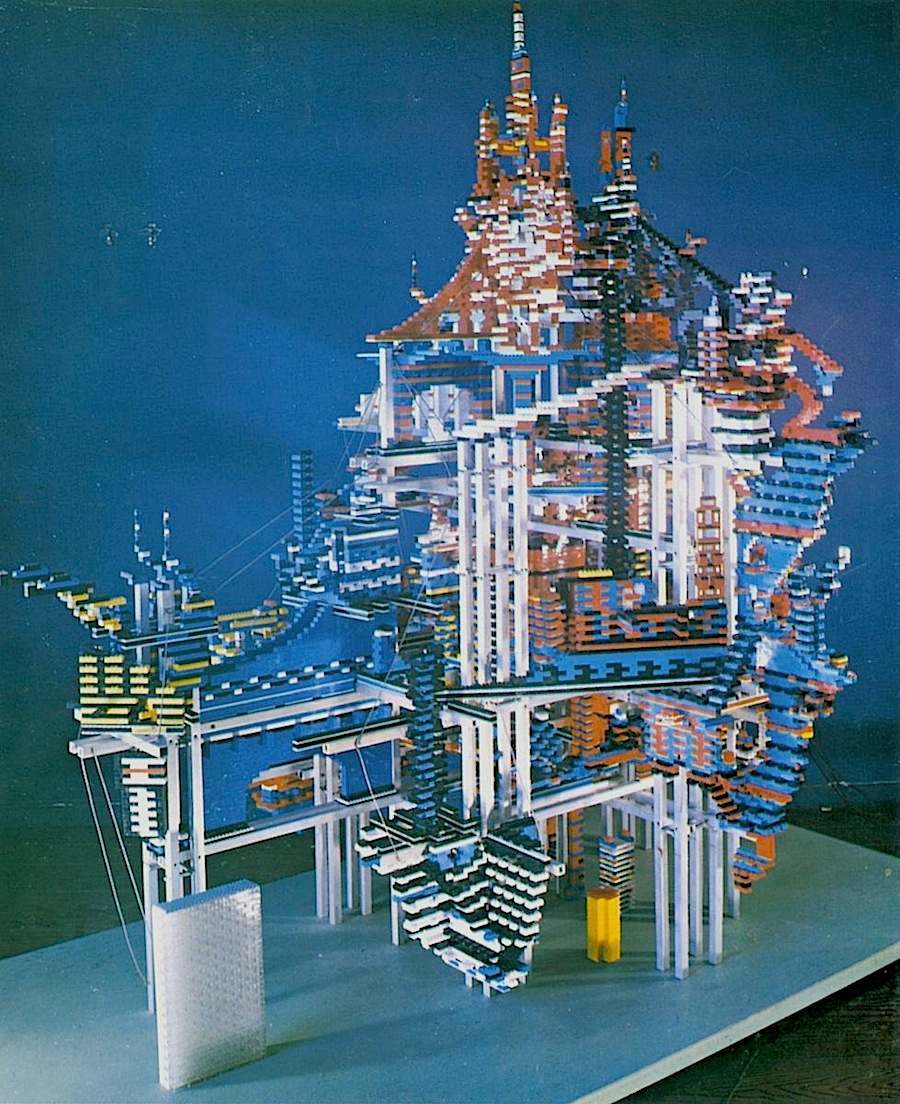

The cover for Cannibals and Christians features a photograph of a model Mailer designed for a future metropolis which he called “Mile High City.”

It looks more like the kinda thing you’d find on a science fiction novel or maybe a book on architecture.

Well, yes. Mailer described it as a “vertical city of the future more than a half mile high, near to three-quarters of a mile in length, with 15,000 apartments for 50,000 people.”

Okay. And did he think people would want to live there?

That was one of things Mailer wondered–whether “a large fraction of the population would find it reasonable to live one hundred or two hundred stories in the air.”

Understandable. So, how big is this model?

About seven feet tall.

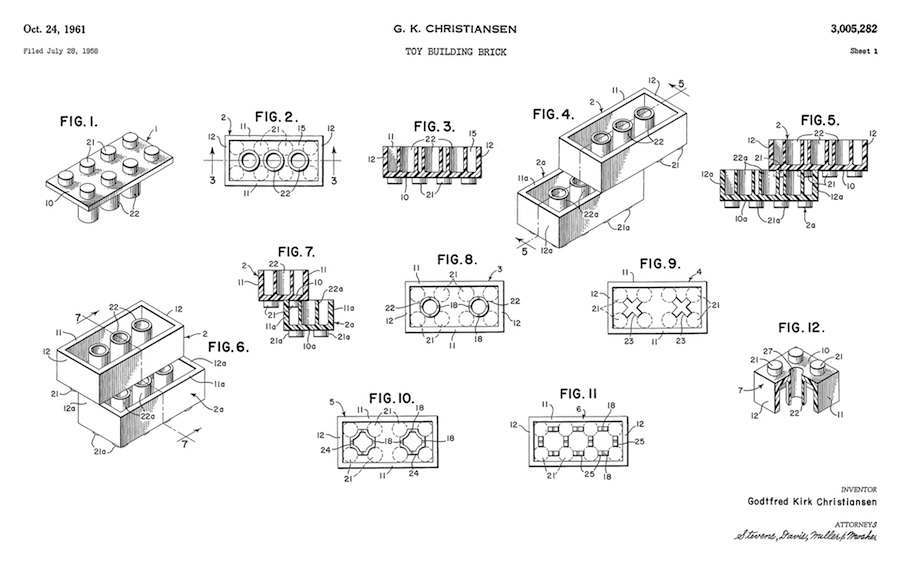

And what’s it built with?

Lego bricks. About 20,000 Lego bricks.

Lego bricks? I thought Mailer hated plastic?

He did. He hated the fact he couldn’t smell it, taste it, and that plastic felt “flat and dead” as he wrote in a letter to a friend:

“I’ve been working with plastic, 10,000 pieces of plastic, on an idea I have for a new kind of city. I think my ideas about plastic are right: handle 10,000 pieces of plastic and you feel flat and dead.”

He also thought the sound the Lego bricks made when clicked together was “obscene”.

But of course…So what was his bug with plastic?

He thought plastic would wreak havoc on the environment.

Back to Mile High City–how and when did it all come about?

Mailer started work on Mile High City in 1965. His son Michael had received a Lego set for his birthday. Mailer looked at these red, white and blue cubes and thought he could use them to build something extraordinary.

Really?

Yes.

Why?

Well, Mailer had been writing about architecture. In his column for Esquire—The Big Bite–in May and August 1963, he wrote against “the plague of modern architecture” describing it as “a plague which sits like a plastic embodiment of cancer over our suburbs, office buildings, schools, prisons, factories, churches, hotels, motels and airline terminals.”

He thought modern architecture reflected the “totalitarianism” that had “slipped into America with no specific political face.” It proliferates and “rests like an incubus upon the American landscape.”

Say what…?

Mailer didn’t like modern architecture.

Obviously…

Modern architecture was totalitarian architecture. It destroys the past leaving people “isolated in the empty landscapes of psychosis, precisely that inner landscape of void and dread which we flee by turning totalitarian styles of life.”

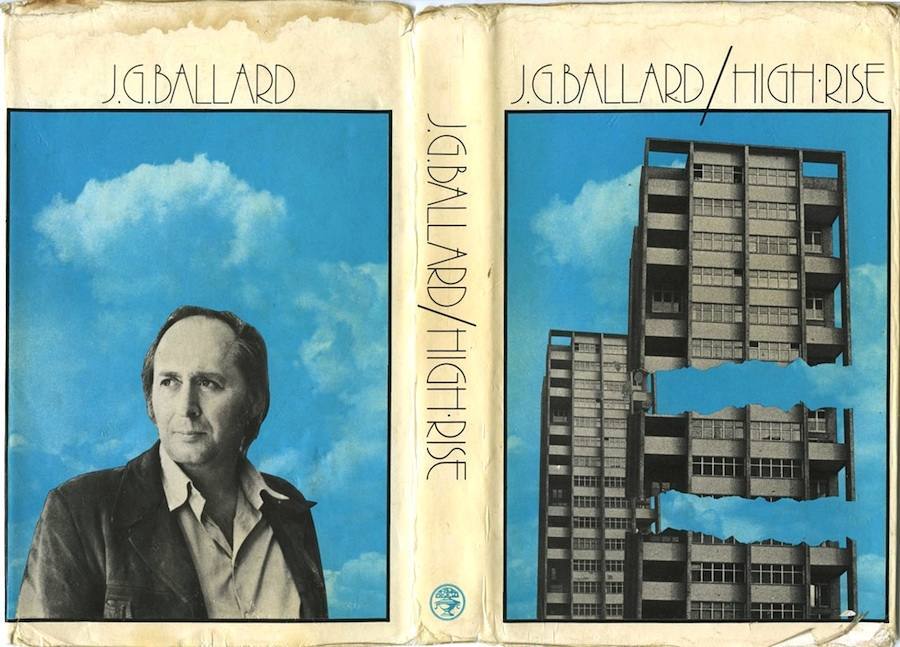

Sounds like something out of J. G. Ballard…

You mean like Ballard’s novel High Rise (1975)? Or, maybe his novella Concrete Island (1974)? Humanity alienated yet ultimately acquiescent to the sterility and austerity of the brutality of the modern world–a tower block, or a massive concrete roundabout on the Westway that becomes like Crusoe’s desert island–but this Crusoe does not leave the island. Just as Dr Robert Laing sits eating the dog on his balcony after the brutal events in High Rise.

First edition cover of J. G. Ballard’s ‘High Rise’ (1975). via

Yeah…if you say so…

With Mailer it was more about building a city upwards rather than spreading out across the landscape. He wrote:

If we are to spare the countryside, if we are to protect the style of the small town and of the exclusive suburb, keep the organic center of the metropolis and the old neighborhoods, maintain those few remaining streets where the tradition of the nineteenth century and the muse of eighteenth century still linger on the mood in the summer cool of any evening, if we are to avoid a megalopolis five hundred miles long, a city without shape or exit, a nightmare of ranch houses, highways, suburbs and industrial sludge . . . then there is only one solution: the cities must climb, they must not spread, they must build up, not by increments, but by leaps, up and up, up to the heavens.

‘Megalopolis five hundred miles long’?

That’s where J. G. Ballard predates Mailer.

He does?

Yes. Ballard wrote a short story Concentration City in 1957. In it he pictured an infinite city that contains everything known to its inhabitants. It stretches infinitely outwards and upwards. There is hardly any trees and damn little wildlife. No one knows what lies beyond the city or if there is any “free space” out there.

And Mailer wanted to ensure we had free space by building upwards?

He was envisioning New York in the future–America in the future.

Really?

In 1964 there had been a lot of hoohah after some academics claimed the population of America would hit 400,000,000 by 2016. Eighty percent of that 400 million would be living in cities.

Okay. So, back to this Lego city Mailer built–what was the deal?

Well, once Mailer had his idea about building a city he had two friends–Charlie Brown and Eldred Mowery–build it for him.

Mailer didn’t build it himself?

No, he hated plastic, remember? As Brown told Peter Manso in his oral biography Mailer His Life and Times:

Norman hated [Lego]. He didn’t want to touch them. They were plastic, and they made–as he said, and I quote–“an obscene noise when clicked together”; therefore I had to be the one who clicked them together.

Charlie Brown would drive out to the Lego factory in New Jersey. He drove Mailer’s ’61 Falcon with the top down. He bought and carried crates of Lego bricks–so many red, so many white, so many blue, and so on. Brown had to do this on his own as there was only room in the car for him and the crates.

As Brown goes onto explain to Manso:

Eldred and I would unload the crates and bring them up to the apartment. To give Norman his due, he’d occasionally come down and carry a box. We put them in the living room, all the furniture shoved aside, which created an absolute mess. [Mailer’s wife] Beverly was beside herself and there were a million people there all the time, friends who came visiting. All in all, we were at it for two months, though it felt like years.

According to Brown, there was “no actual design, only a basic concept.” They built a “frame out of aluminum, with five-foot legs, on a four- by eight-foot sheet of plywood”. Eldred had originally been hired to do some work around the apartment–including building a tightrope for Mailer. Instead, Mailer had him work on his Lego city.

Charlie Brown:

Norman’s got all these crazy ideas about what he wants to do–Norman the engineer–and at one point he wanted Eldred to put all these strange trapdoors in the model city. He’d make an appearance and say, “No, no, you’ve got it all wrong,” or “Make me something that looks sort of like this,” and he’d pick up a few blocks…

Wait. I thought he didn’t like to touch plastic?

He didn’t. But it’s damned hard not to touch plastic–it’s everywhere…

Okay. What else did Brown say?

He said, Norman would pick up a few blocks and say:

“Now put these together, glue them, and I’d like them to go here.” He was constantly appearing with a sheaf of papers in his hand, and his secretary, Annie, would be running around making phone calls and taking dictation. He would pop in for fifteen minutes, supervise, then disappear.

Eldred had a much finer structural sense than Norman. He doesn’t talk very much, but he did have a few words to say to me about Norman’s ability to design things. But he’d never say straight, “Norman, you don’t know what the fuck you’re talking about.” Instead it was “Well, I don’t know. How about if we do so-and-so, because otherwise it will fall over?” Beverly meanwhile was always yelling, “I can’t stand this shit in my living room.” He didn’t pay any attention, though, and they’d just throw things at each other.

Mailer would have carried on tinkering with his Mile High City indefinitely. It was finally finished after a visit from an interested party at the Museum of Modern Art, who wanted to exhibit it at the museum. That was when it was declared to be finished.

What happened with MOMA?

Unfortunately they couldn’t get the damned thing out of the apartment. Mailer had “guys with cranes…all sorts of people doing research: Should we take the glass out of the front window? Can we cut the door?”

Charlie Brown:

He refused to disassemble it because we couldn’t have reassembled it exactly the same way, and he wanted it precisely the way it was. Finally he say, “Eldred, build a fence around it. Fuck it, that’s it. It stays.”

And there it did stay–taking up a third of the living room–and then he put it on the cover of Cannibals and Christians.

Is Cannibals and Christians worth reading?

Hell yeah. But if you want to start reading Mailer try Armies of the Night or An American Dream, Advertisements for Myself or The Presidential Papers to get a feel for the man. Or The Naked and the Dead, The Executioner’s Song or The Fight or Marilyn or Tough Guys Don’t Dance. Then go on to Harlot’s Ghost and Ancient Evenings. You’ll find something in there that’s well worth keeping.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.