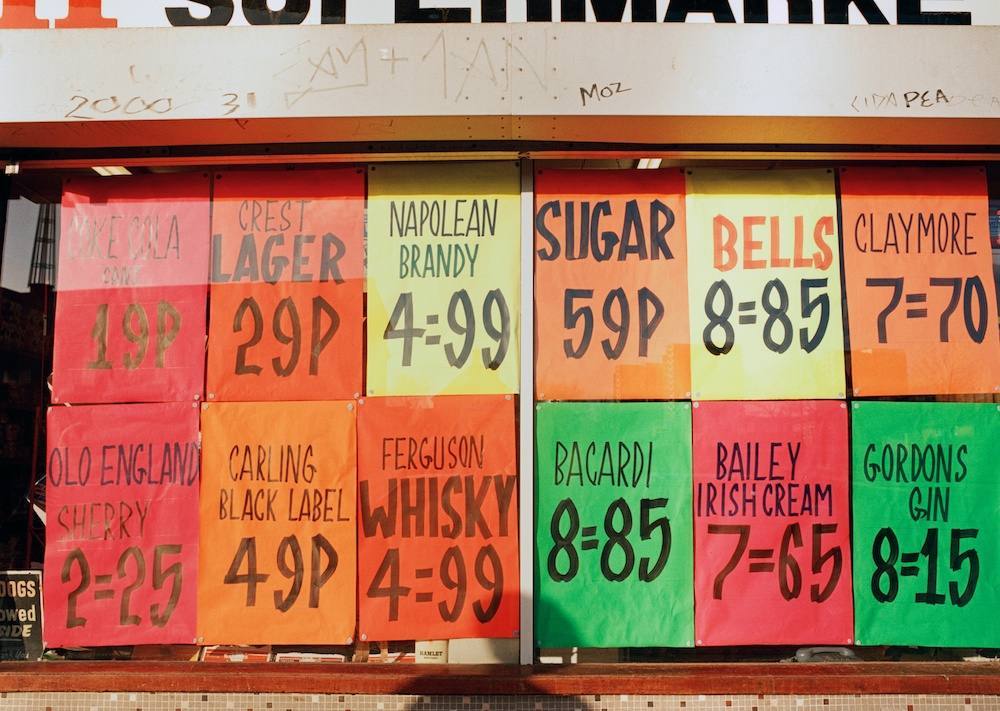

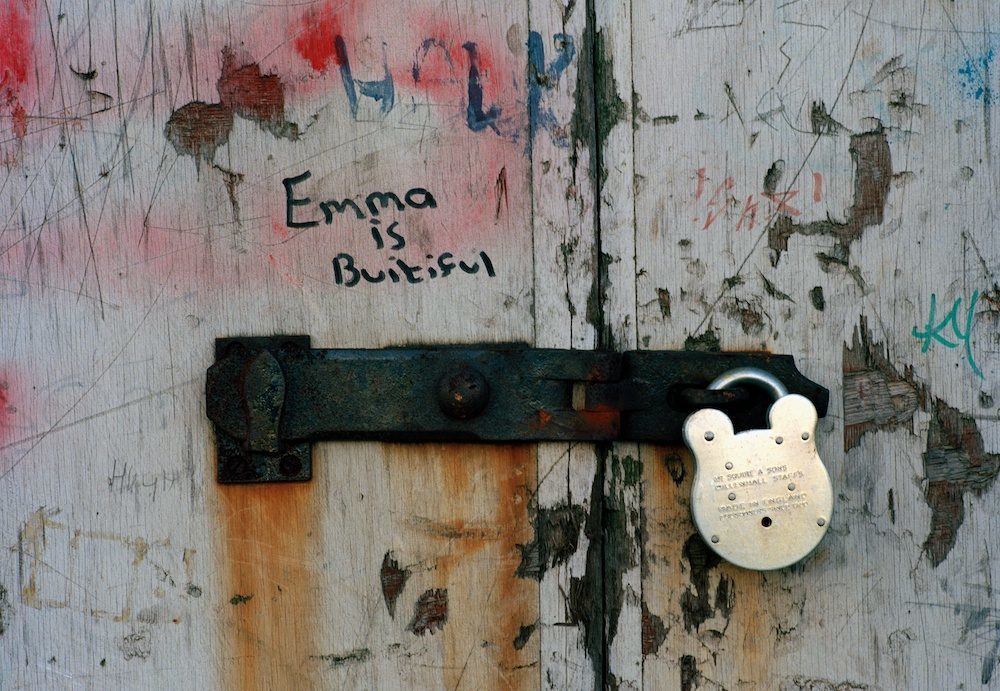

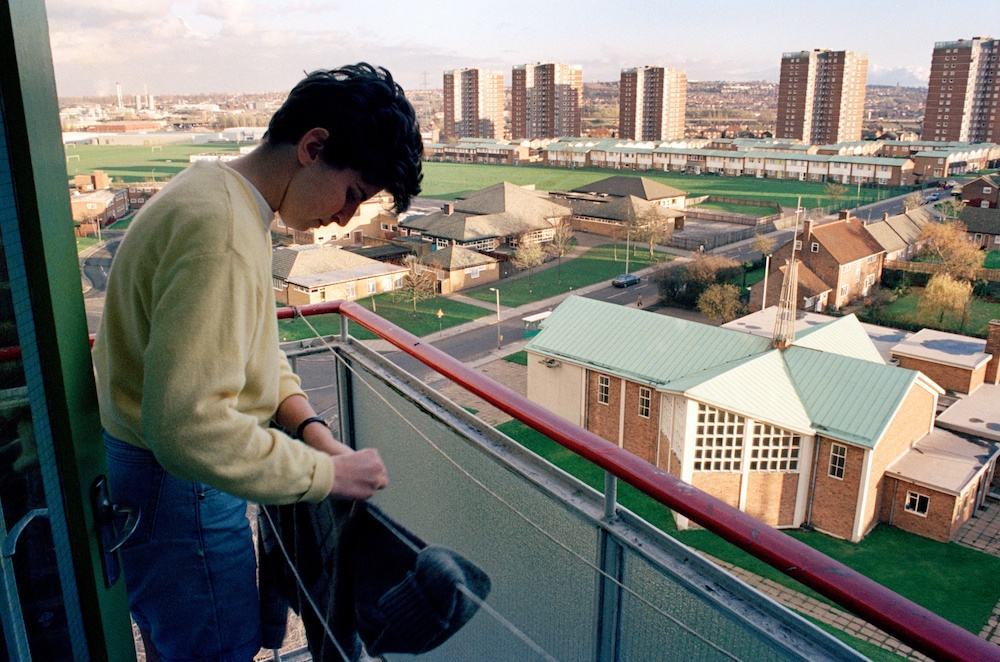

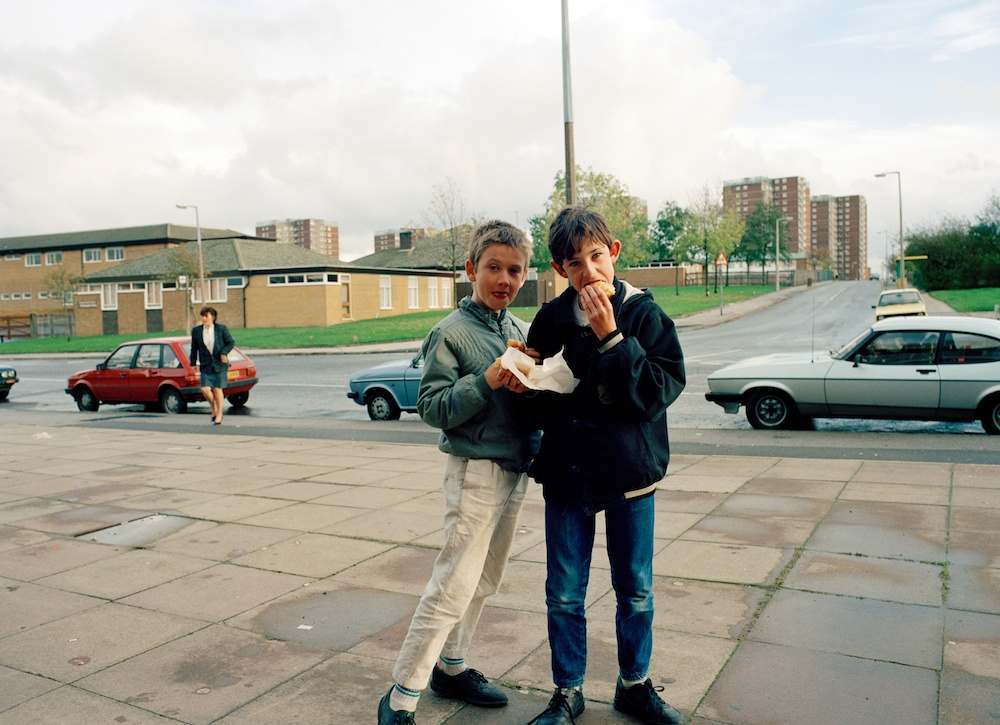

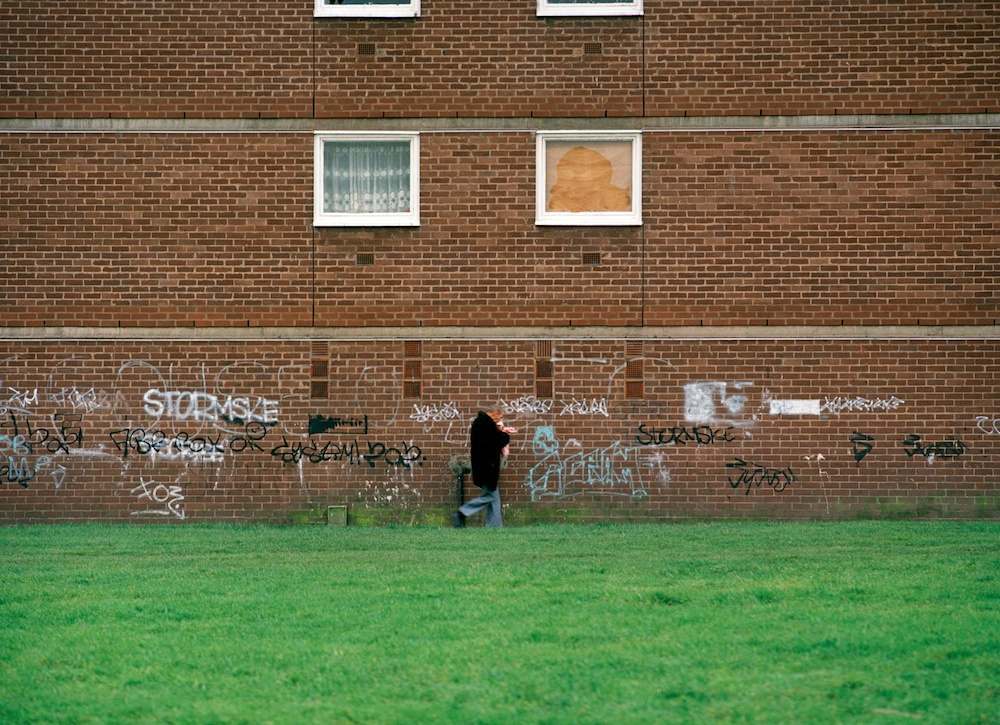

What does your home mean to you? Is it sanctuary or trap? A bit of both? Does it connect or disconnect? Robert Clayton’s photography of the Lion Farm estate in Oldbury, West Midlands, focuses our thoughts on what home is. If everything that humans make begins with an idea, the temptation is to look at a 1960s estate and wonder what the idea was and who thought it a good one?

Clayton, as with all better artists, is keen to show and not tell. He wants to show that “many people did live here and why shouldn’t the wider population be more aware of what it was like to do so? I was interested in conveying the facts of life here and allowing the audience to come to their own conclusions.”

His work does not use housing estates as objects of curiosity for the purchasing-power classes to goggle. In 2008, Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, moved into a bed and breakfast hotel (£40 a night) and spent her days being filmed advising poor, northern housing-estate life how to eat well and really enjoy vegetables. This celebrity colonisation of places where actual people actually live in the hope of being infantilised by one of the unreal moralising elite continued the work of former Tory MP Matthew Parris. For a 1984 World in Action documentary, Parris tried to live on welfare payments. As Jarvis Cocker succinctly put it, plucky Parris would “live like common people”. Parris tried to last a week in a Newcastle bedsit on £26.80, then the supplementary benefit paid to a single unemployed man. He struggled and failed to live in this alien landscape. His adventure, as with Fergie’s mission, was all about the vain and comfortably off using poverty and the estate as entertainment for us, the fourth wall.

Clayton is not them. Thank god. Keen not to impose himself on a scene and create hostility, Clayton won the trust of the residents and was welcomed inside their homes. “I just asked people to carry on what they were doing and I would sit down too, work out my composition and wait, ” he says. “I would chat a little maybe or just observe. One, two or maybe three frames later I was done… I suspect people can quite instinctively feel at ease once your approach conveys that you present no threat.”

We get to see the place and the people in a neglected planned community. We can also look at each part of the place in isolation. Take one element of the estate – the playground. Clayton explains his view to PhotoMonitor:

“I wanted to photograph in a very accurate manner an environment that a lot of people have to endure in their daily lives. So the playgrounds for example – they were hardly used and why should they be? One element of them was old sewer pipes (I believe left over from the days of construction) that were set into cement and deemed a suitable apparatus for children to play on/in – a cheap and nasty add on. Jonathan Meades in his accompanying essay in the books refers to this in that he questions the lack of maintenance afforded to such estates once they were built. They were Utopian in that they helped solve a real housing and public health crisis in the UK (look at Nick Hedges work Make Life Worth Living) and this is to be applauded, but then councils tended to walk away and neglect their upkeep.

“Today, in areas that are desperate for public/social housing, these tower blocks are real assets with big waiting lists to acquire one. This is despite the long term neglect they have suffered. Most of the blocks in my work were demolished which I think was a real shame. So the playgrounds – why? Is this good enough – of course not! I was glad where I grew up my local play park was better than this and I wanted to expose this. Did anyone responsible for this genuinely believe this was good? Would they design this for their children?”

It reminds us of what Jane Jacobs wrote in her 1961 collection of essays, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Published in 1961, around the time well-intentioned planners and architects were preparing to construct the Lion Farm Estate, her words on urbanism ring true:

But look what we have built with the first several billions: Low-income projects that become worse centers of delinquency, vandalism and general social hopelessness than the slums they were supposed to replace. Middle-income housing projects which are truly marvels of dullness and regimentation, sealed against any buoyancy or vitality of city life. Luxury housing projects that mitigate their inanity, or try to, with a vapid vulgarity. Cultural centers that are unable to support a good bookstore. Civic centers that are avoided by everyone but bums, who have fewer choices of loitering place than others. Commercial centers that are lackluster imitations of standardized suburban chain-store shopping. Promenades that go from no place to nowhere and have no promenaders. Expressways that eviscerate great cities. This is not the rebuilding of cities. This is the sacking of cities.

Communities are made of flesh, not concrete.

Jonathan Meades looks at what it is and what it is not. Rob’s work features in a new book called Estate with an essay by Jonathan Meades (available for sale, limited edition of 750 only, at www.stayfreepublishing.co.uk):

What changed the complexion of social housing was the practice of “decanting” into second-tier projects, sociopaths, recidivists, junkies, the unemployable, the wilfully dependant, and the cast-out victims of another cruel wheeze of that era, the mendaciously named Care in the Community. Clayton captured Lion Farm on the eve of this calamitous invasion which would result in the partial destruction of the estate…

His Lion Farm was obviously not the green-and-pleasant land which the post-war consensus strove for and did, sometimes, achieve. But nor was it a dystopian slum. What Clayton recorded is valuable precisely because it shows neither a model estate, a showplace, nor a sink. The typical is elusive. It’s a hard thing to capture because it surrounds us and doesn’t shout. It is the 90 per cent which is habitually overlooked as we set our sights on the exceptional 10 per cent: on the one hand picture-postcard tourism, on the other frissons of delight at noxious slums.

There was nothing special about Lion Farm Estate. It could have existed in more or less any British conurbation which was on the cusp of losing its raison d’être. What is special is Clayton’s humane rendering of it as a time capsule which emphasised ordinariness. This was how it was for millions of people in the early 1990s.

In The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness, Rebecca Solnit explains her view of the home:

Admiring houses from the outside is often about imagining entering them, living in them, having a calmer, more harmonious, deeper life. Buildings become theaters and fortresses for private life and inward thought, and buying and decorating is so much easier than living or thinking according to those ideals. Thus the dream of a house can be the eternally postponed preliminary step to taking up the lives we wish we were living. Houses are cluttered with wishes, the invisible furniture on which we keep bruising our shins. Until they become an end in themselves, as a new mansion did for the wealthy woman I watched fret over the right color of the infinity edge tiles of her new pool on the edge of the sea, as though this shade of blue could provide the serenity that would be dashed by that slightly more turquoise version, as though it could all come from the ceramic tile suppliers, as though it all lay in the colors and the getting.

It;s hard if not impossible to think anyone fretted over the look and colours of Lion Farm, an oddly bucolic name for such a desolate urban sprawl.

It takes time and heart to turn a building into a home.

When you’re renting and your landlord sees you as inconvenience, a drain on resources, a place to stow the unwanted and unwelcome, values like belonging, safety and community that come from seeing your home as a place of sanctuary are eroded? If the place is the people, neglecting one imperils the other.

All pictures ©www.robclayton.co.uk courtesy of LA Noble Gallery, London

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.