Some of the most passionate interpreters of poverty in the U.S. South have been educated Northerners like W.E.B. Du Bois, Walker Evans and James Agee. Evans and Agee’s book of photographs and essays, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, captured the destitute lives of white Southern tenant farmers during the Great Depression. Evans, Owen Edwards writes at Smithsonian, “wrote the story of America with his camera.” He passed that legacy to students while teaching at Yale, including another Northern chronicler of the South, Baldwin Lee, who began traveling through Louisiana, Florida, Georgia, and other Southern states in the early 1980s.

“Walker Evans had photographed in this area 50 years earlier,” says Lee. “When I was travelling and looking at places he had gone, it shocked me that absolutely nothing had changed. You believed you had stepped back into 1935.” He did not travel South specifically to document the down-and-out. After he became a professor at the University of Tennessee, Lee undertook a 2,000-mile journey through the region, photographing everything that caught his eye. When he returned to his darkroom, he found that portraits of black Americans living in poverty moved him deeply, perhaps because of his own background as a struggling first-generation Chinese immigrant growing up in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

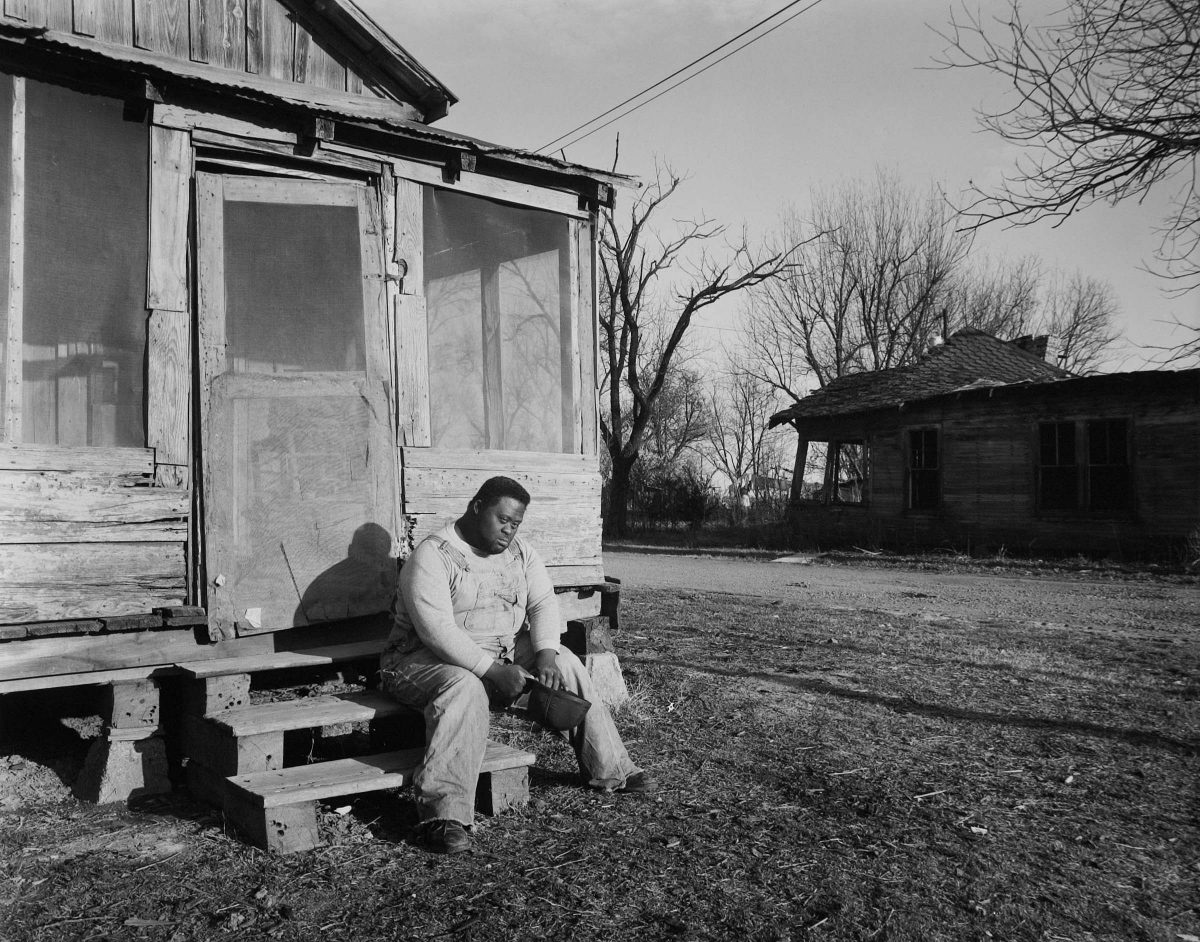

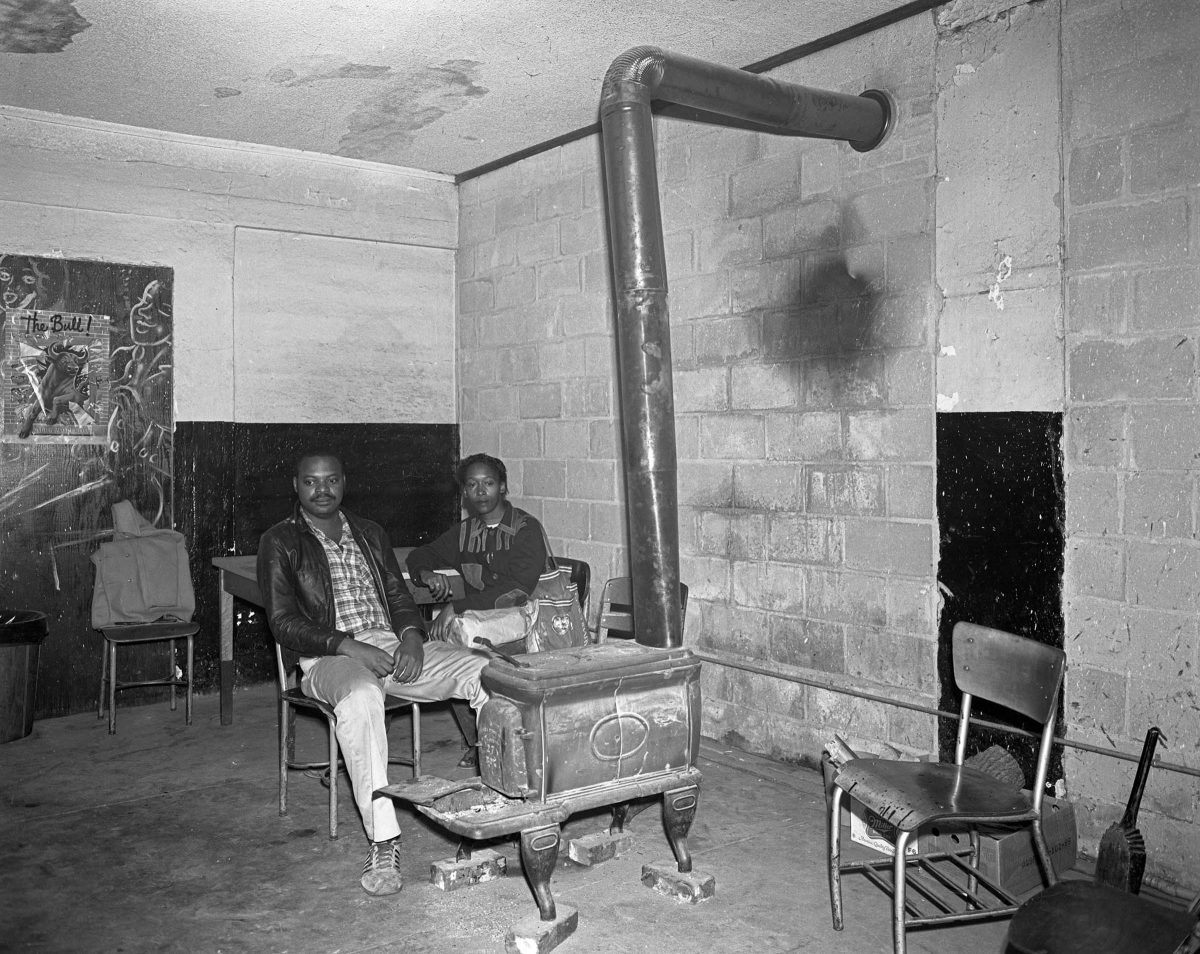

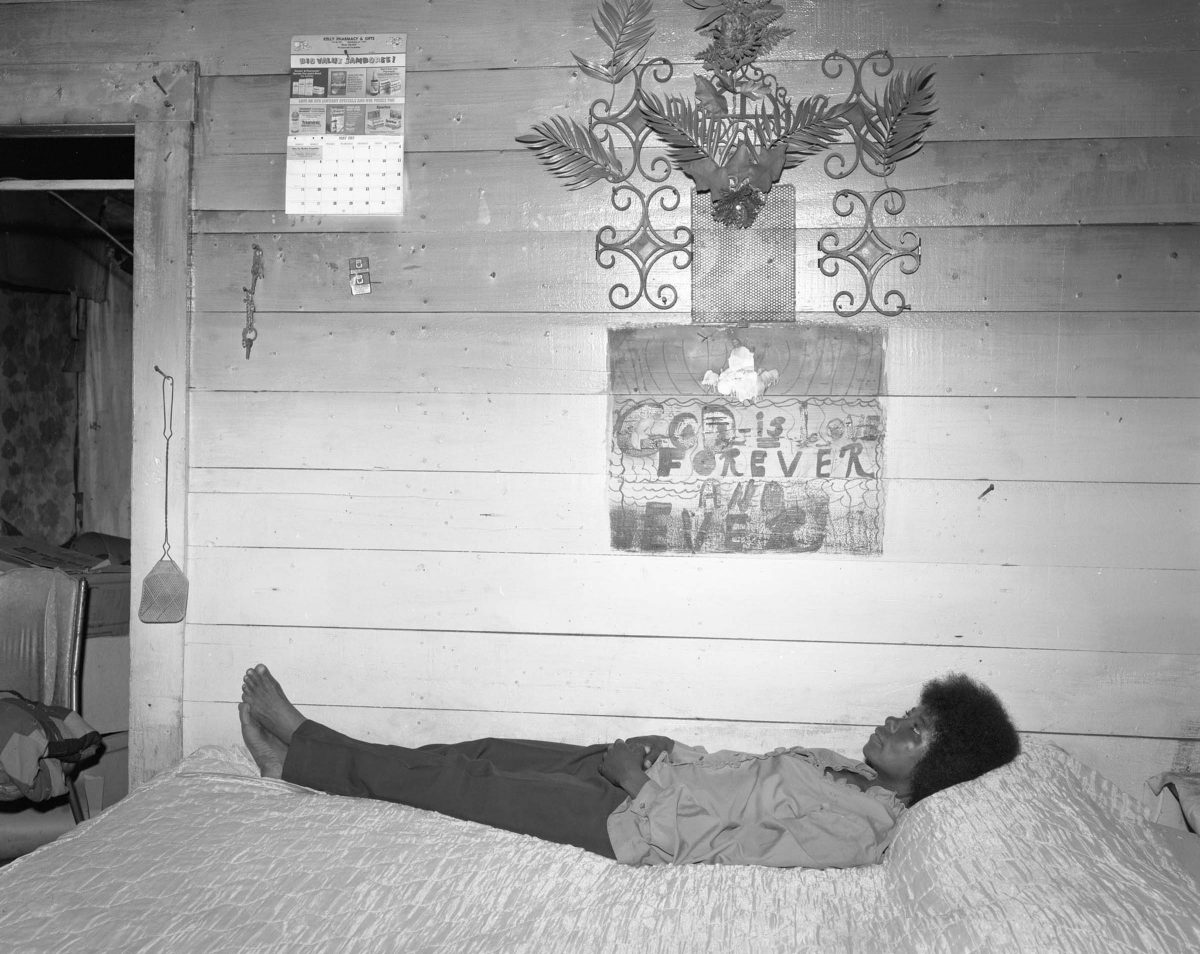

Vicksburg, MS (Alan Pulling Friend) 1984

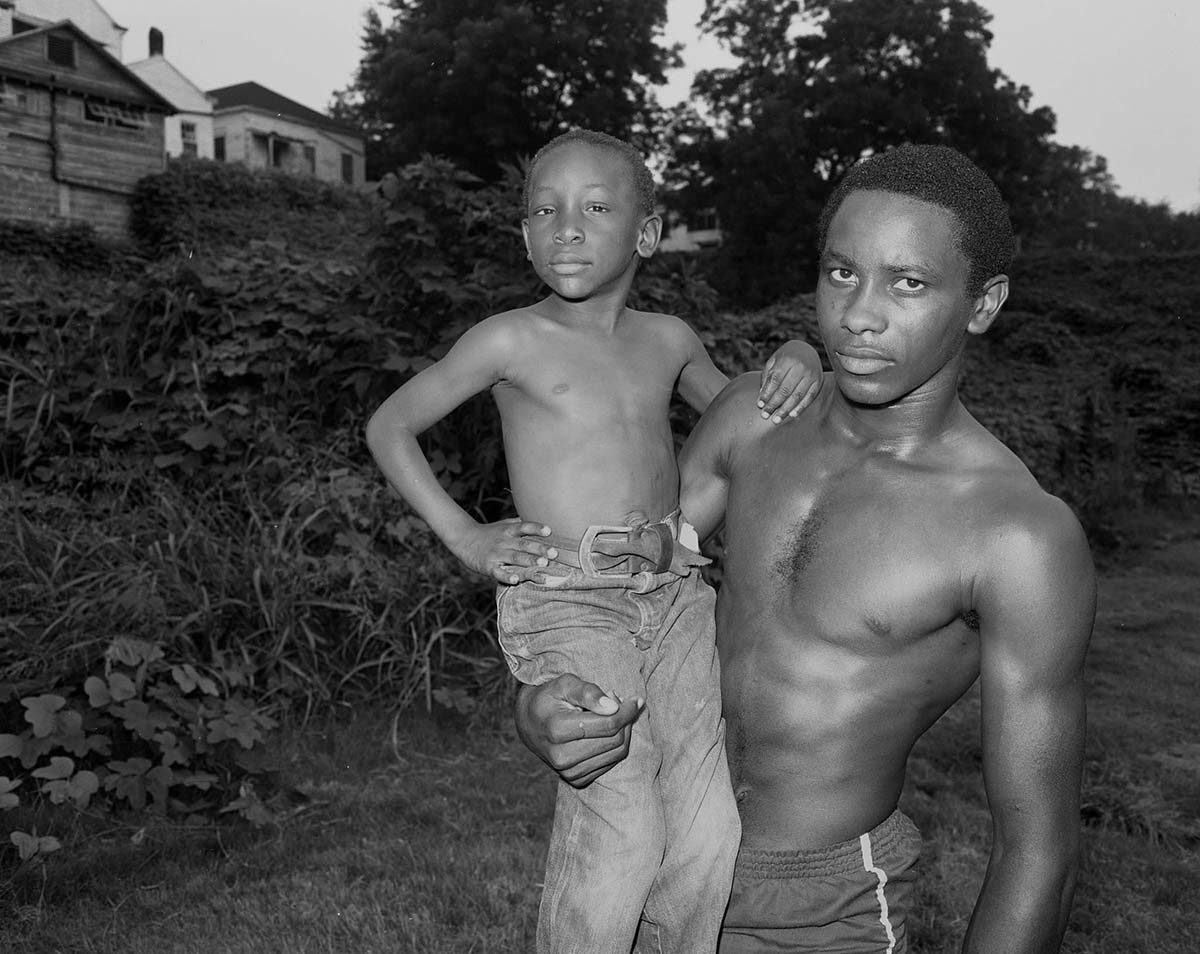

“My work is different from a lot of other people’s work in that I was not particularly interested in the general situation,” say Lee. “It was not my goal to document poverty or economic injustice. It was always based on a very specific human aspect.” Still, these photographs—most of them from 1984-85—show people living in exactly the same conditions that predominated centuries earlier, as Lee himself couldn’t help but notice. As commentary on the times, they tell a story about the country in the late-20th century that resonates loudly in the 21st.

In 1984, President Ronald Reagan’s first term was coming to an end. In announcing his second campaign, the conservative incumbent accused his political rivals of looking backward: “Their government—their government sees people only as members of groups. Ours serves all the people of America as individuals. Theirs lives in the past, seeking to apply the old and failed policies to an era that has passed them by. Ours learns from the past and strives to change by boldly charting a new course for the future.”

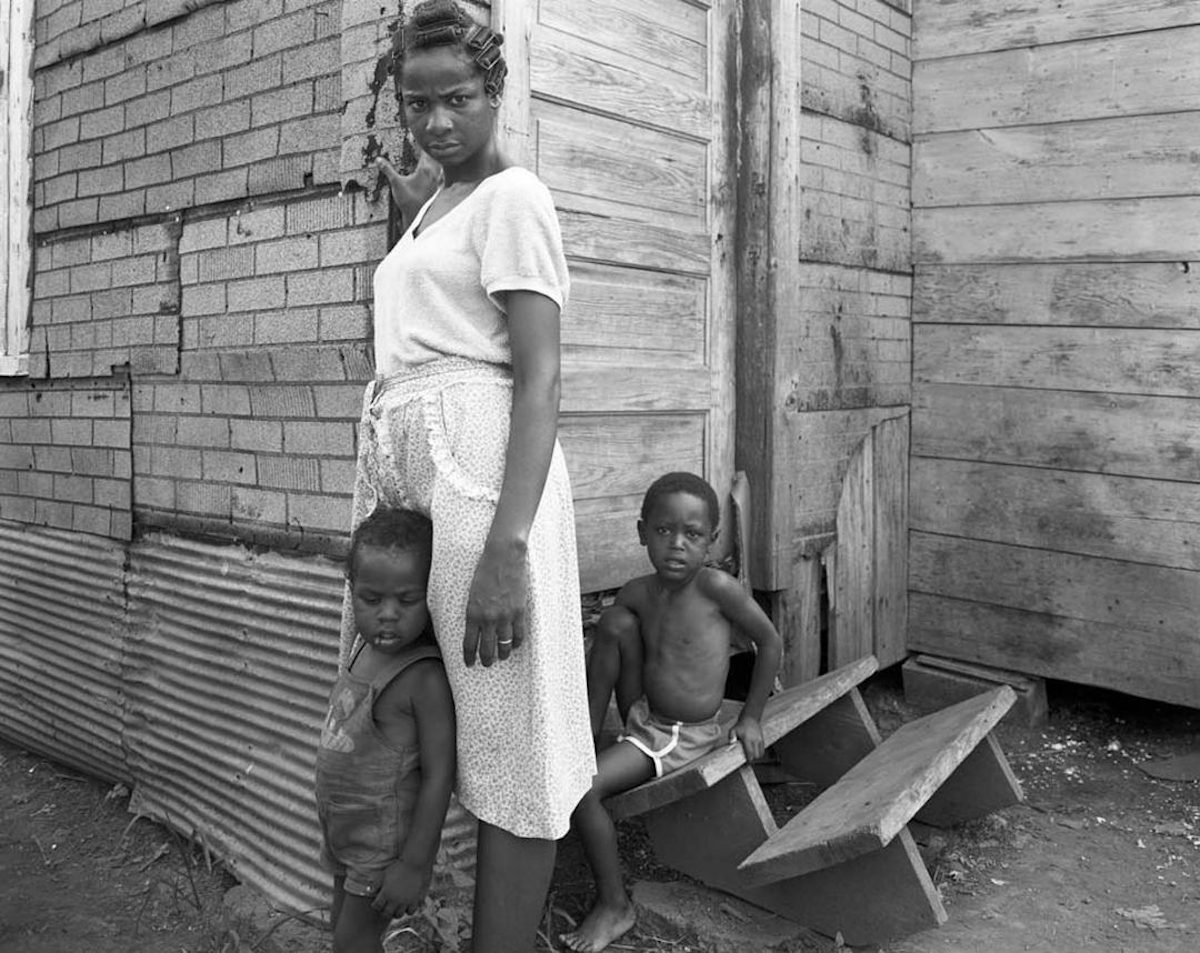

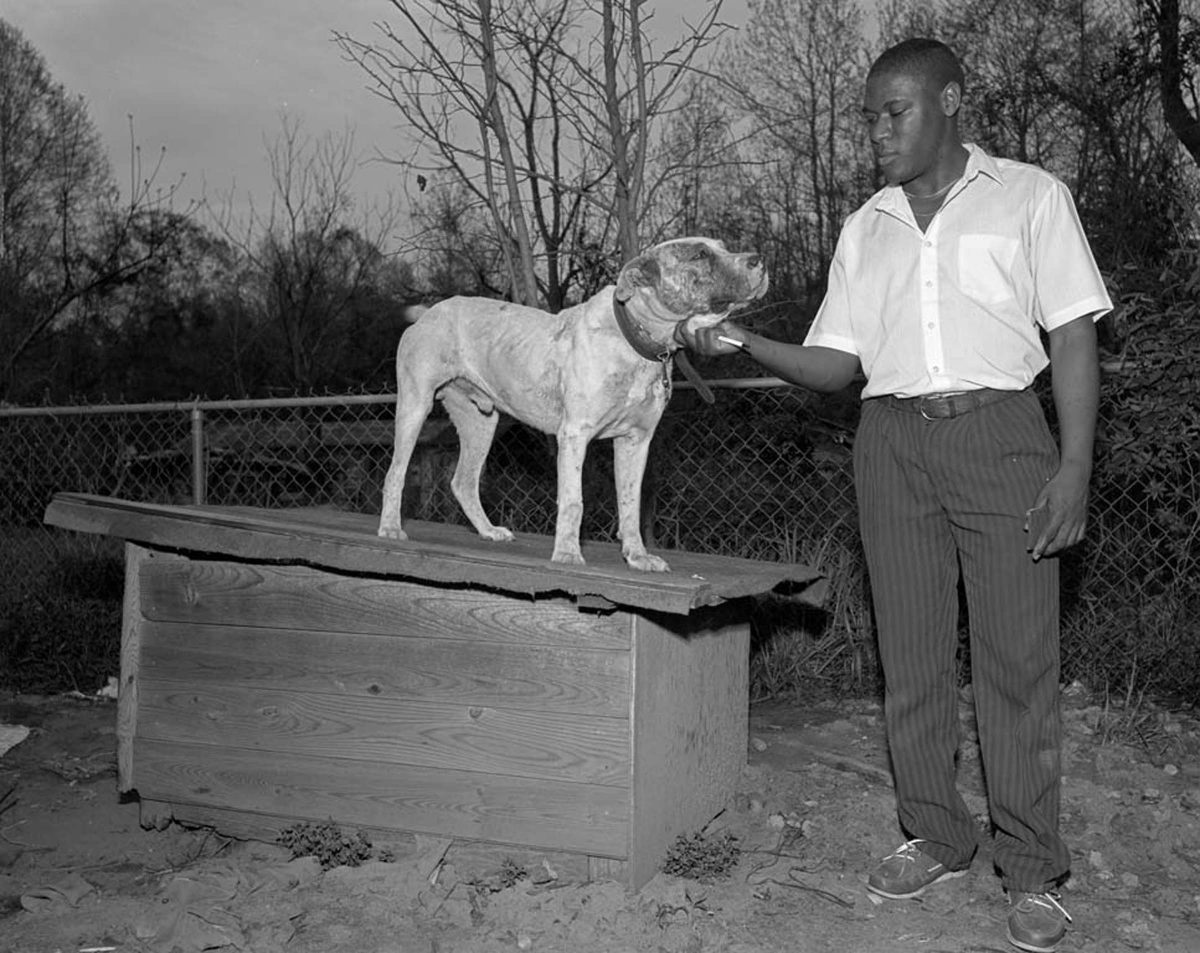

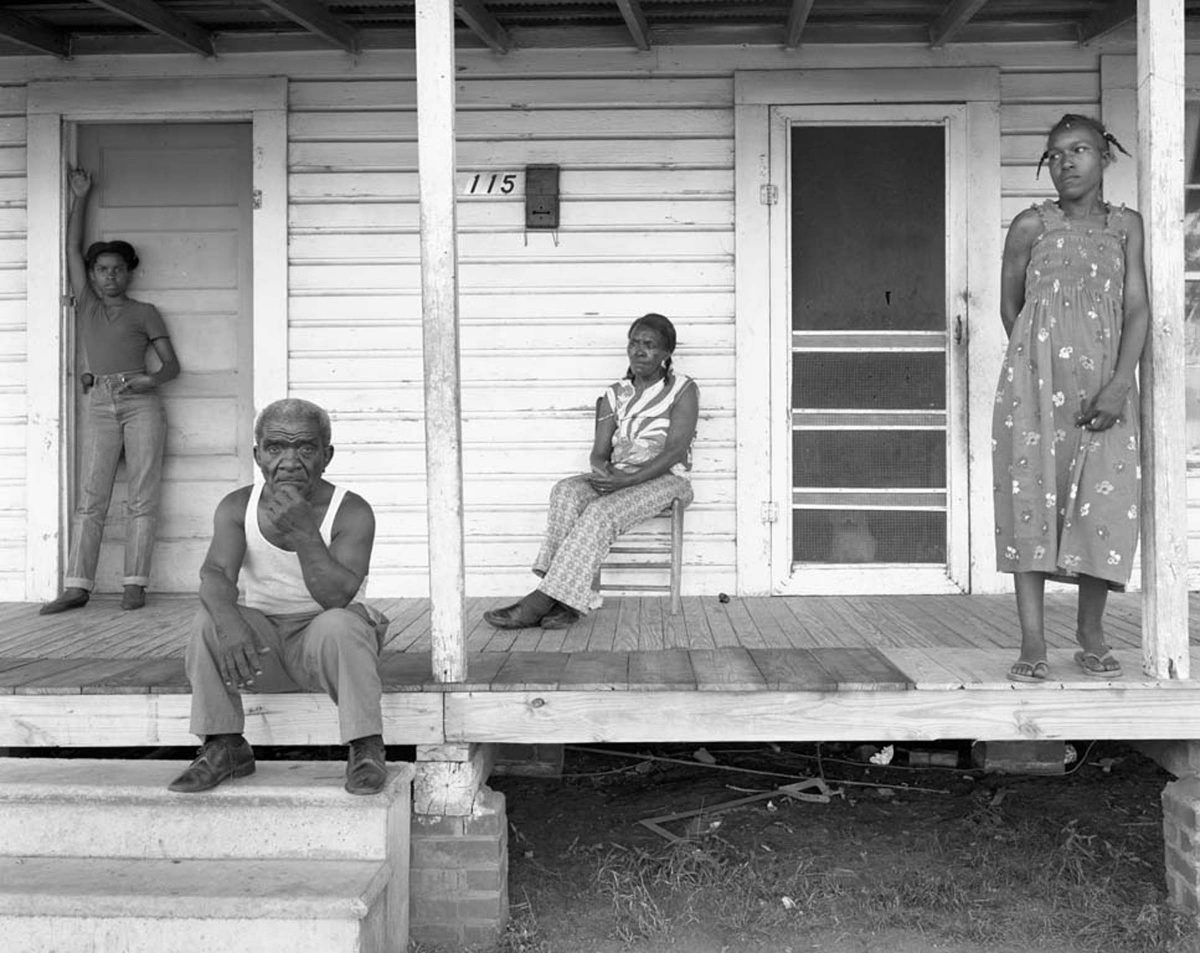

Monroe, LA (Mother and Children) 1985

Yet somehow the same groups of people were historically left out of trickle-down economic policies and the promise of the president’s 1980 campaign slogan, “Let’s make America great again.” But one cannot point to a single bad actor. The two major political parties had swapped the executive office back and forth seven times between the Great Depression and the first, 1980 iteration of “Make America Great Again.” None of the country’s leadership had been able or willing, as longshot Democratic candidate Jesse Jackson said at the time, to “lift the boats stuck at the bottom” despite a New Deal, Great Society, and War on Poverty.

This may not have been the story Lee first set out to tell but it’s hard not to see it in his photographic series, collected as Black Americans in the South, which documents incredible resilience in the face of crushing poverty. One image in particular, of four young children standing hand-in-hand before Nashville’s full-scale replica of the Parthenon, seems like explicit commentary on the gulf between democratic ideals and harsh reality. “I suspect,” writes photographer Mark Steinmetz at Time, “that few are aware of the accomplishments of Baldwin Lee, who, photographing in the South 30 years ago, produced a body of work that is among the most remarkable in American photography of the past half century.”

These photographs are as essential to telling the country’s story as those of Lee’s onetime mentor Walker Evans’ of the American South at the height of the Depression. See Lee’s full online exhibition here.

via Huck magazine

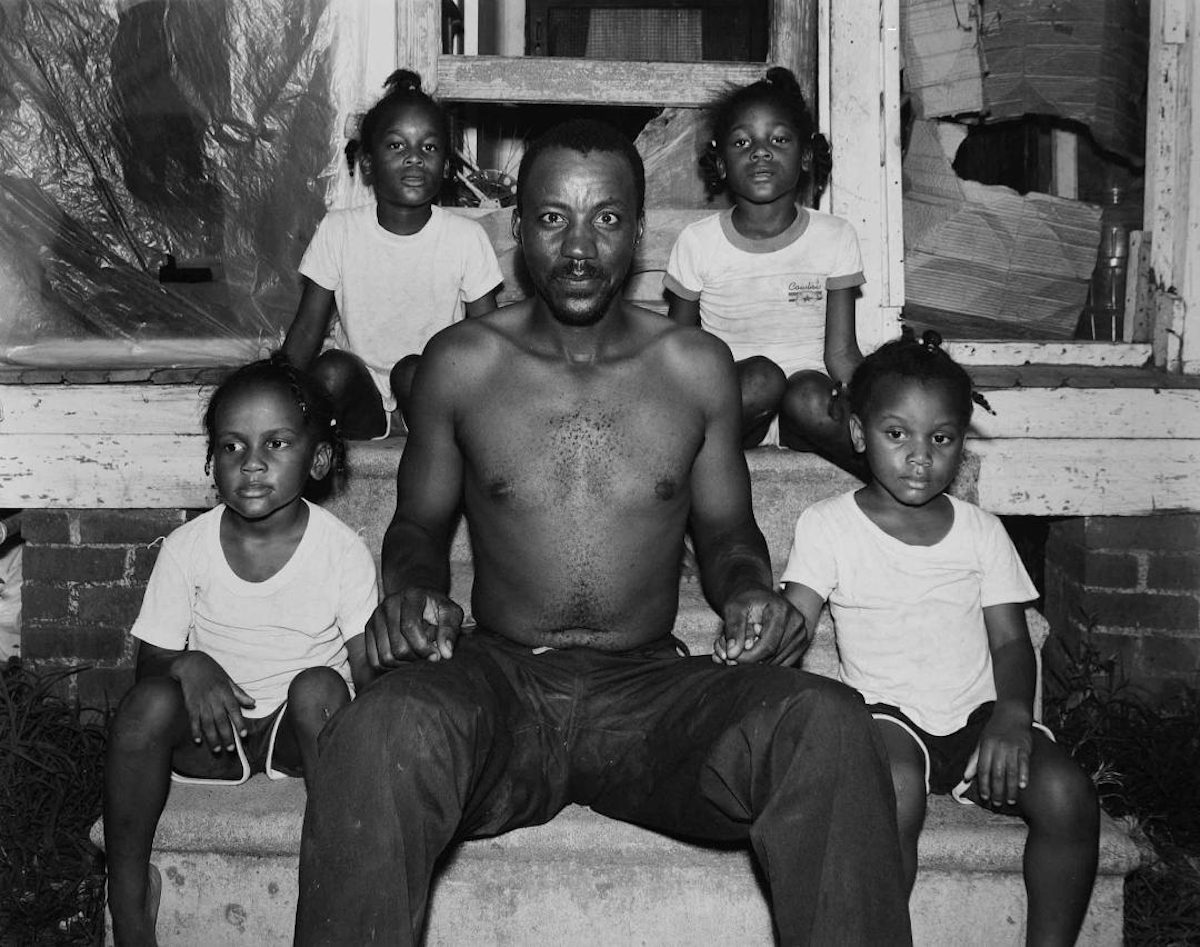

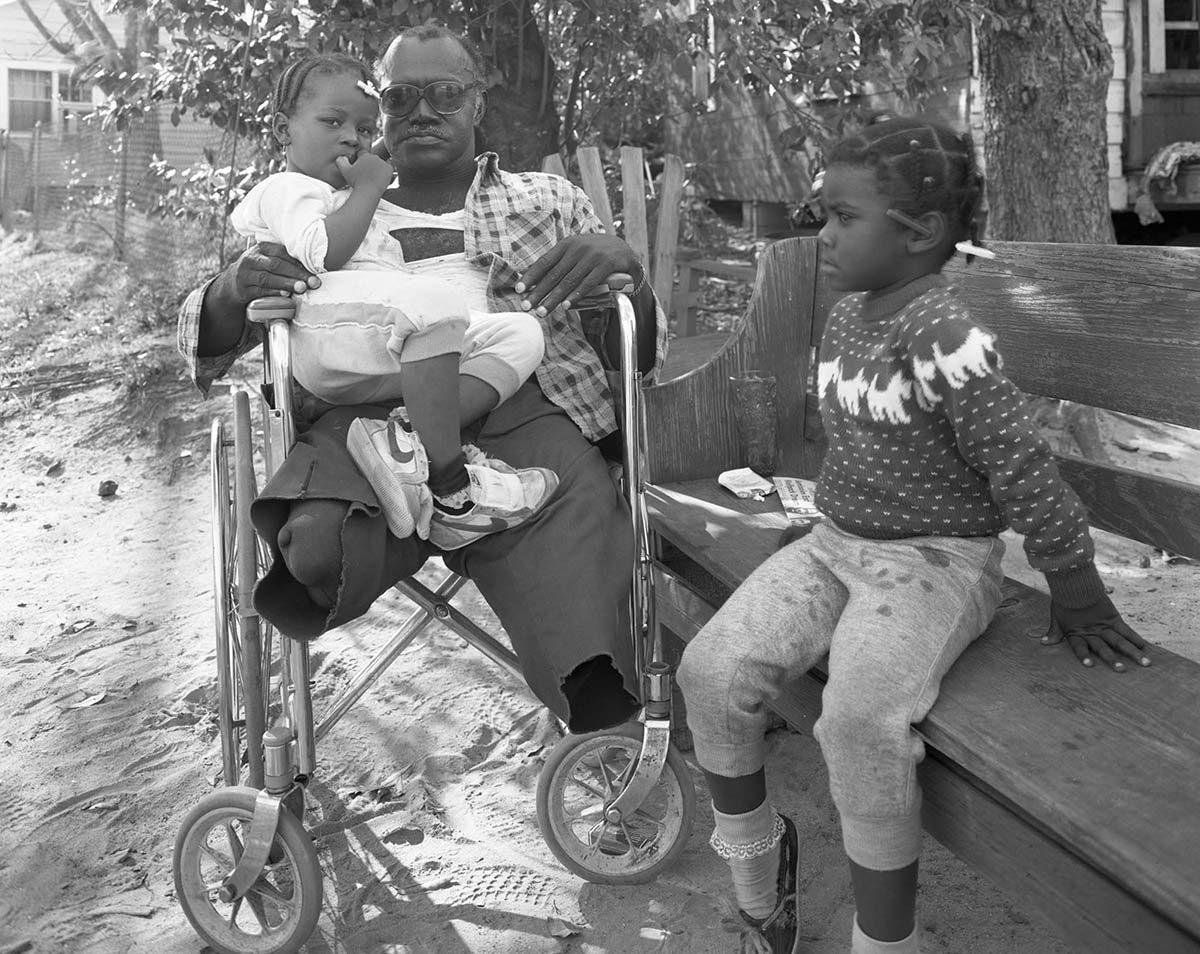

New Orleans, LA (Family on Bench) 1984

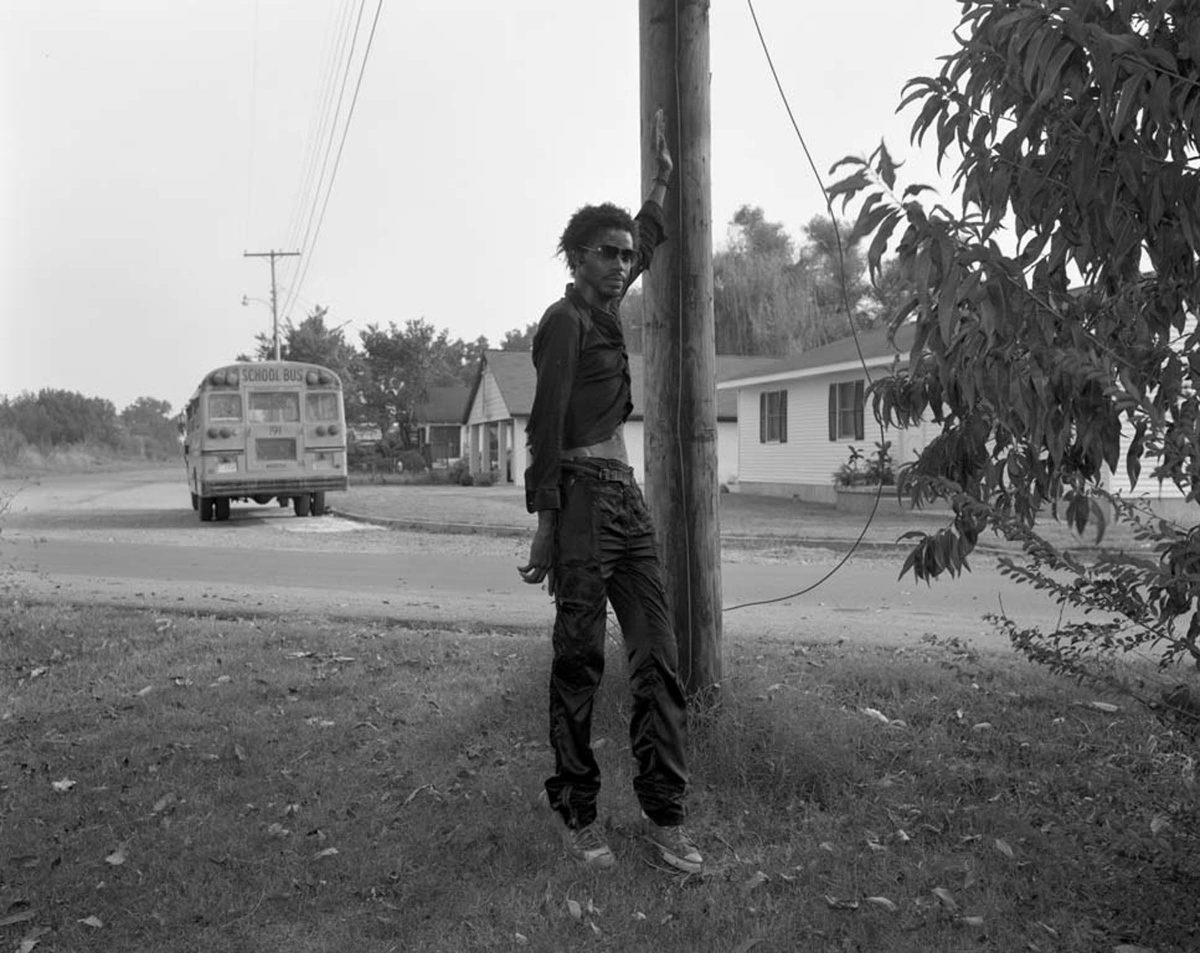

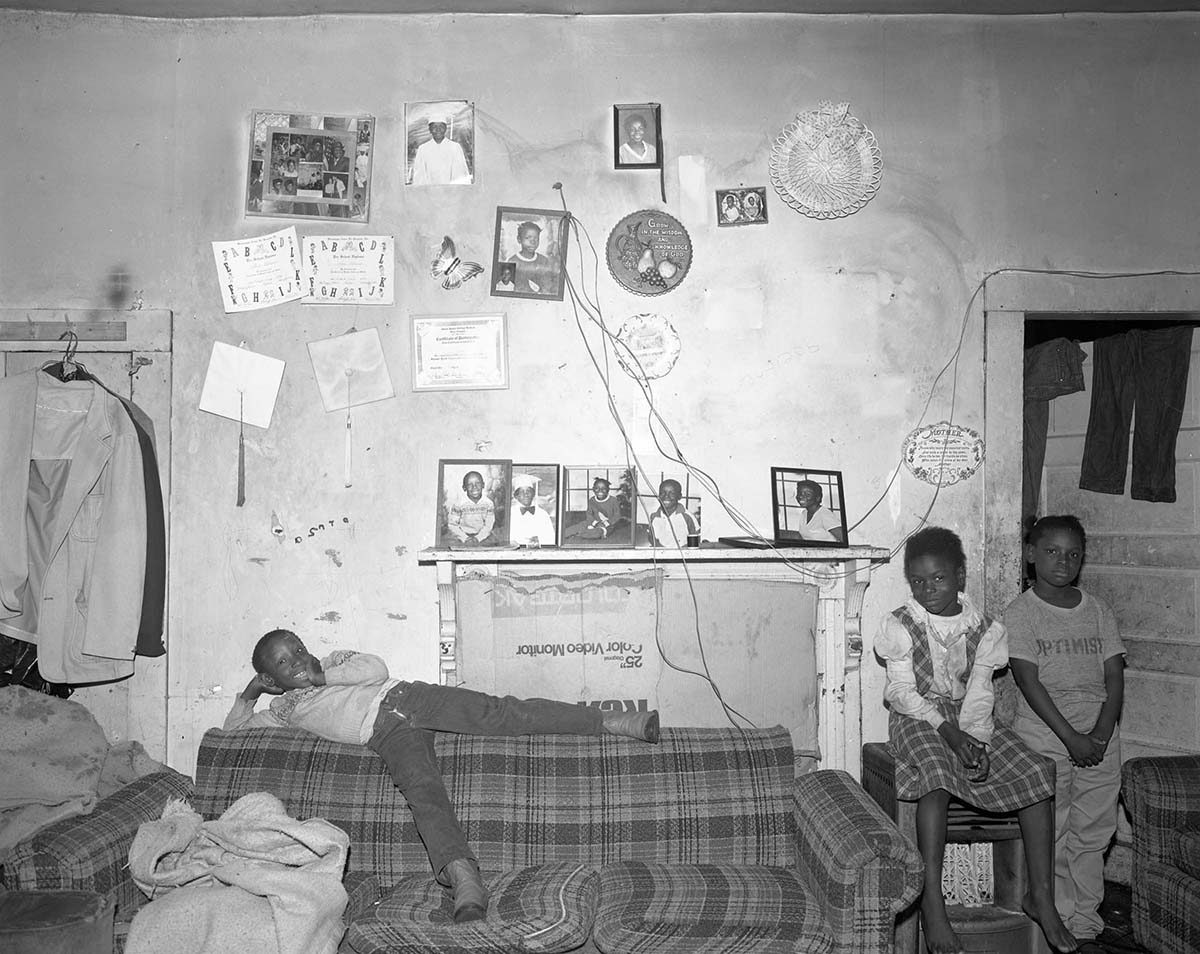

Baton Rouge, LA (Men in Scale) 1985

Lula, MS (Woman Hat) 1984

Vicksburg, MS (Barbershop) 1983

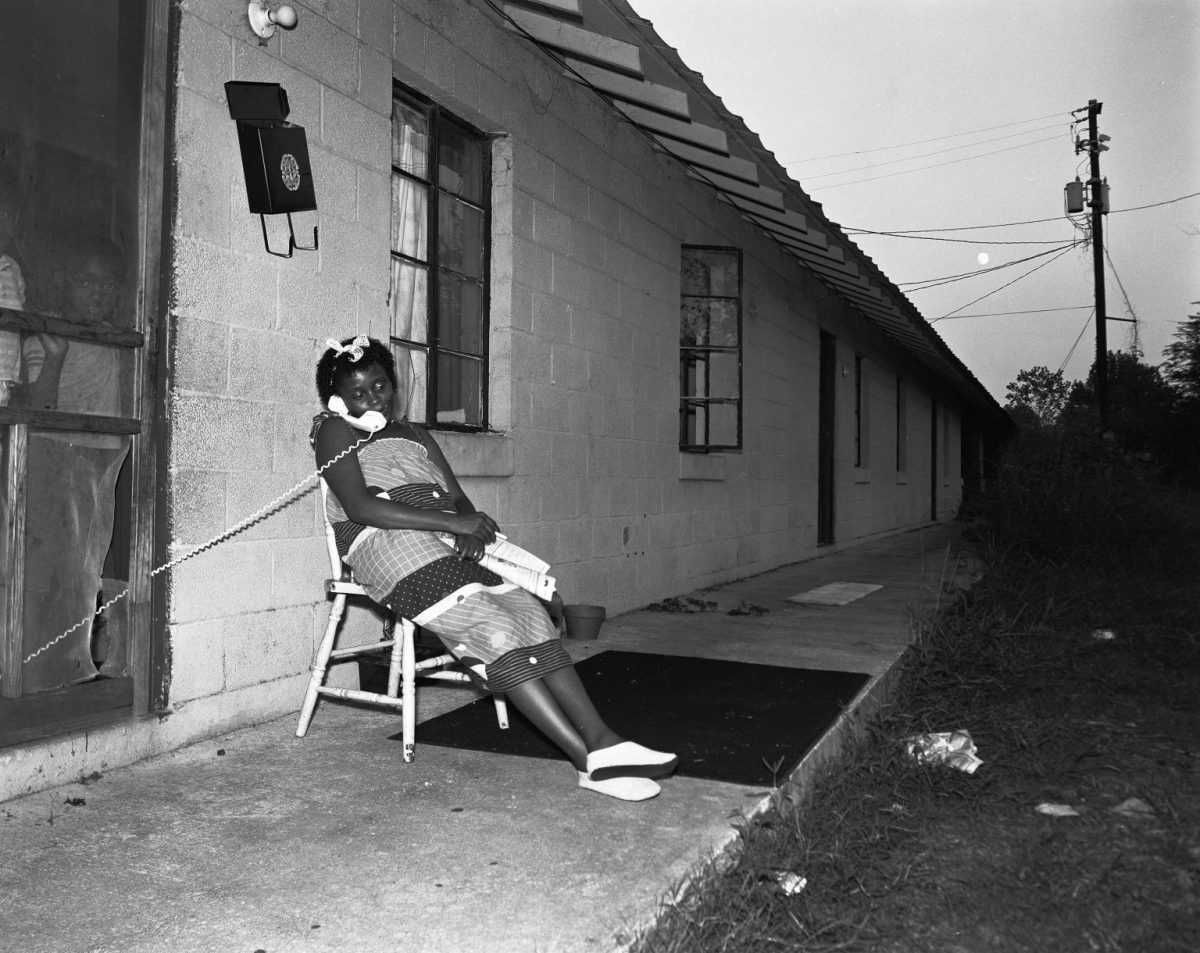

Bessemer, AL Phone Moon) 1984

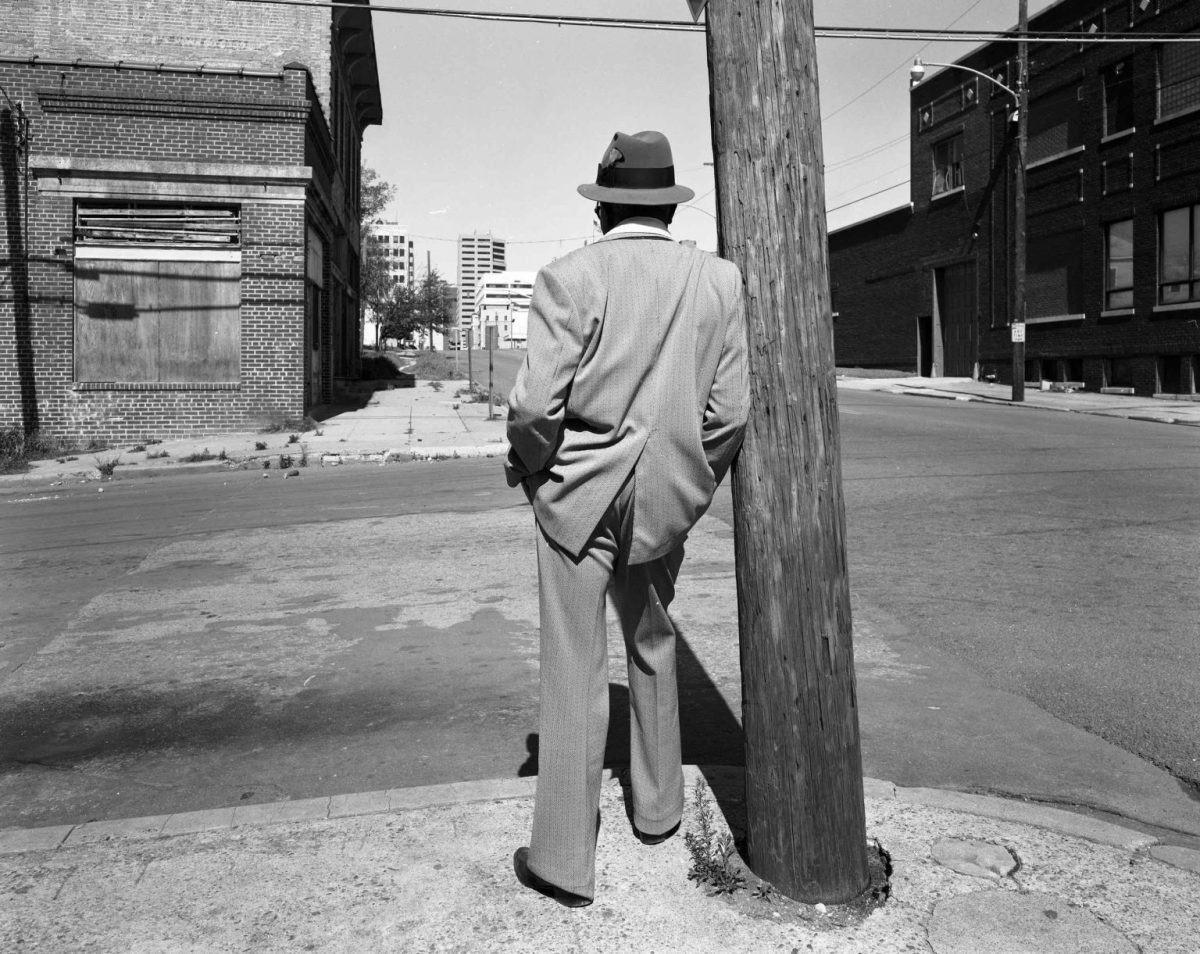

Shreveport, LA (Man’s Back Suit)

Pascagoula, MS (Little Baby Porch) 1985

Vicksburg, MS (Children Holding Hands) 1984

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.