Some writers think their written words are sacrosanct because in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God. The Word comes first and therefore trumps everything. Four Kings and an Ace? Can’t beat the Word. Snake eyes against a noun and a verb? House wins. The Word is Holy. It always comes first. Paddy Chayefsky knew this. He’d proved it. He’d won three Oscars for his writing. Marty, Hospital, and Network. He had little time for directors ‘coz directors just ruined what he wanted to say. Chayefsky knew before the first camera ever turned-over they had to have the word written down so they knew what the hell they were going to shoot. The Word always came first.

Chayefsky was born Sidney Aaron in January 1923. He was sweet Jewish kid who showed an early precocity to use big words and engage adults in startling conversations. This sweet kid’s personality changed when he was conscripted into the US Army during World War Two. In the raw company of his fellow conscripts, Chayefsky found he had to become another person to survive. Another Jewish writer Norman Mailer (also born in January 1923) found similar. To cope, Mailer became a complex multiple-personality: part-Texan Red Neck, part-barroom Irish brawler, part thin-lipped WASP. Mailer filtered his wartime experiences through each of these personalities to create his first work of fiction The Naked and the Dead. He then adopted these identities to use in real life as though there were his own.

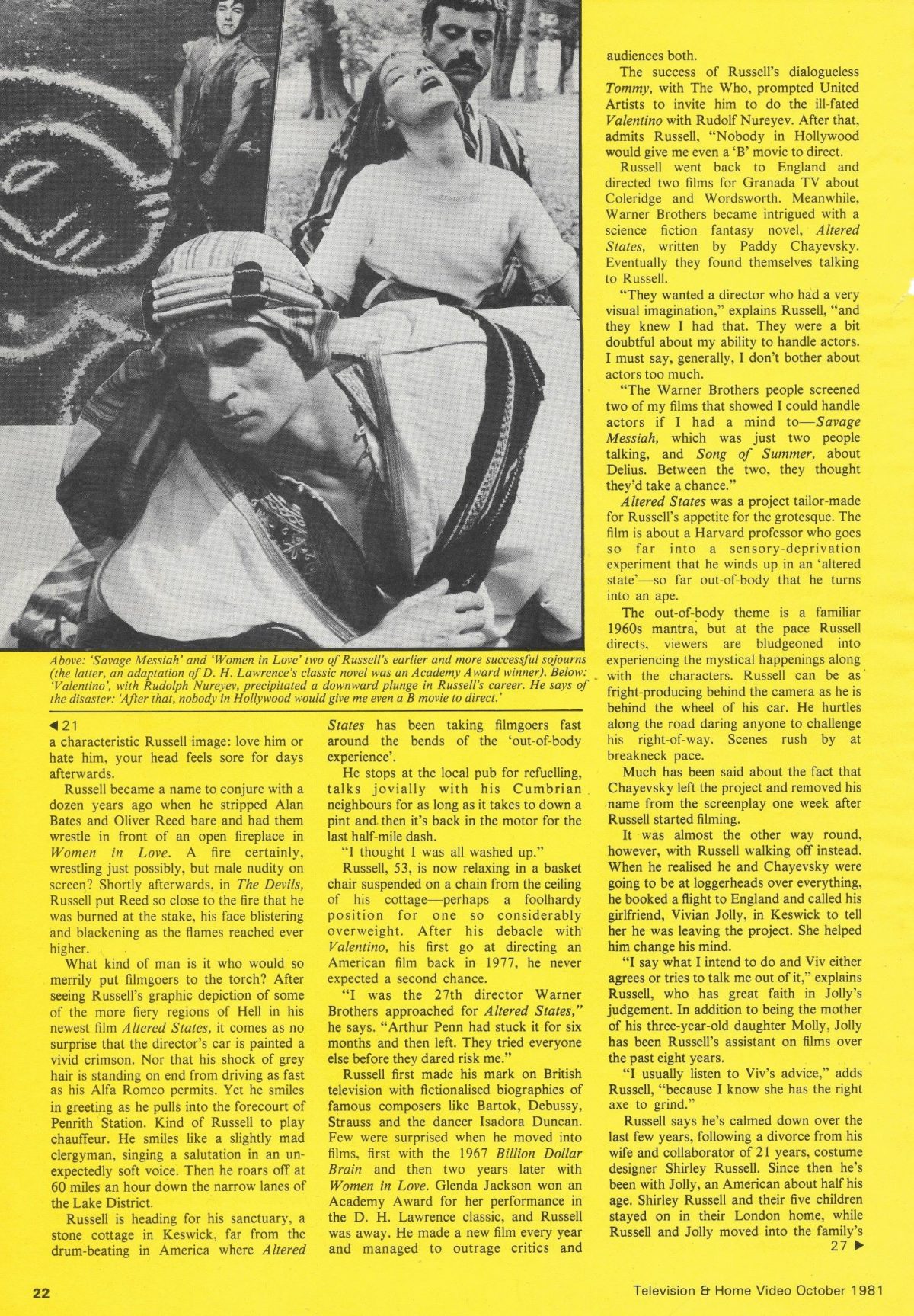

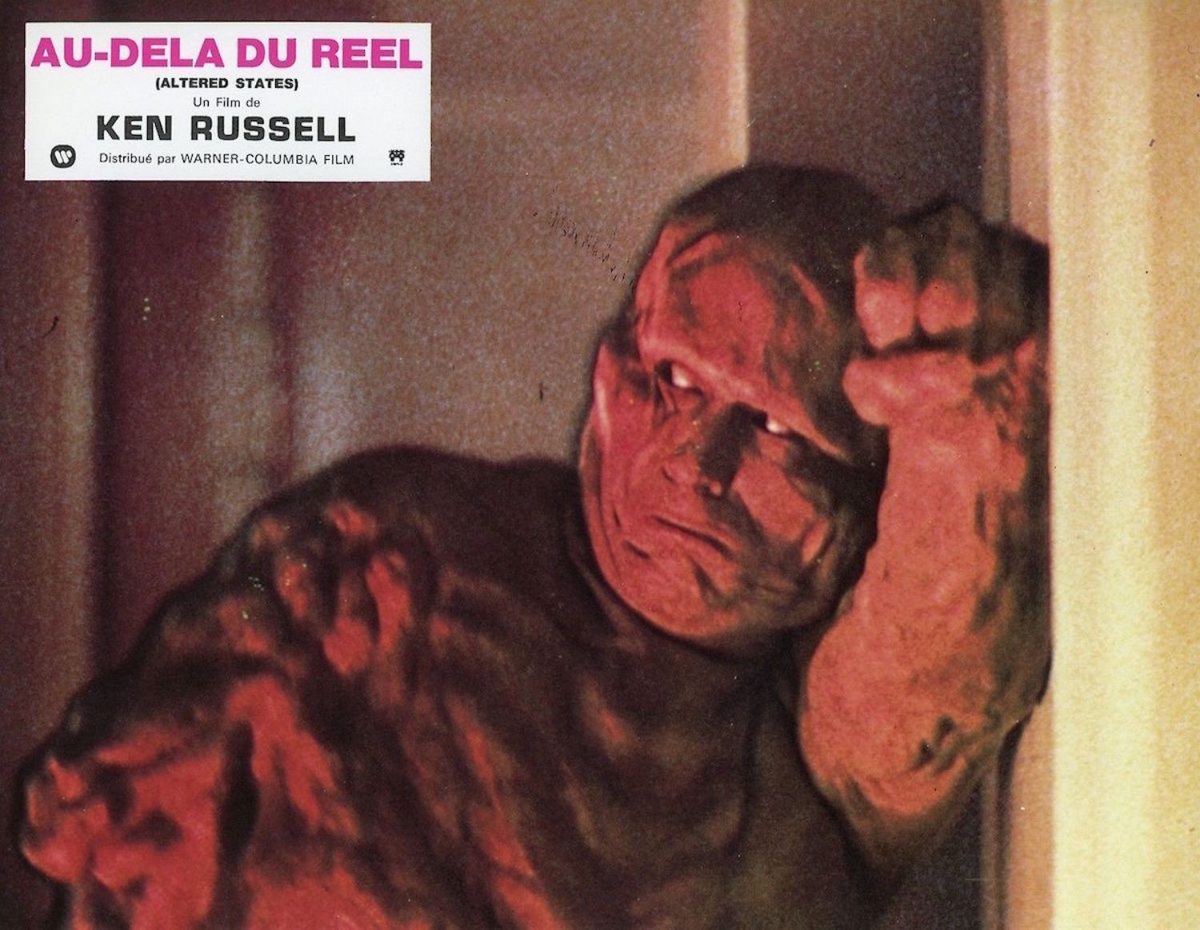

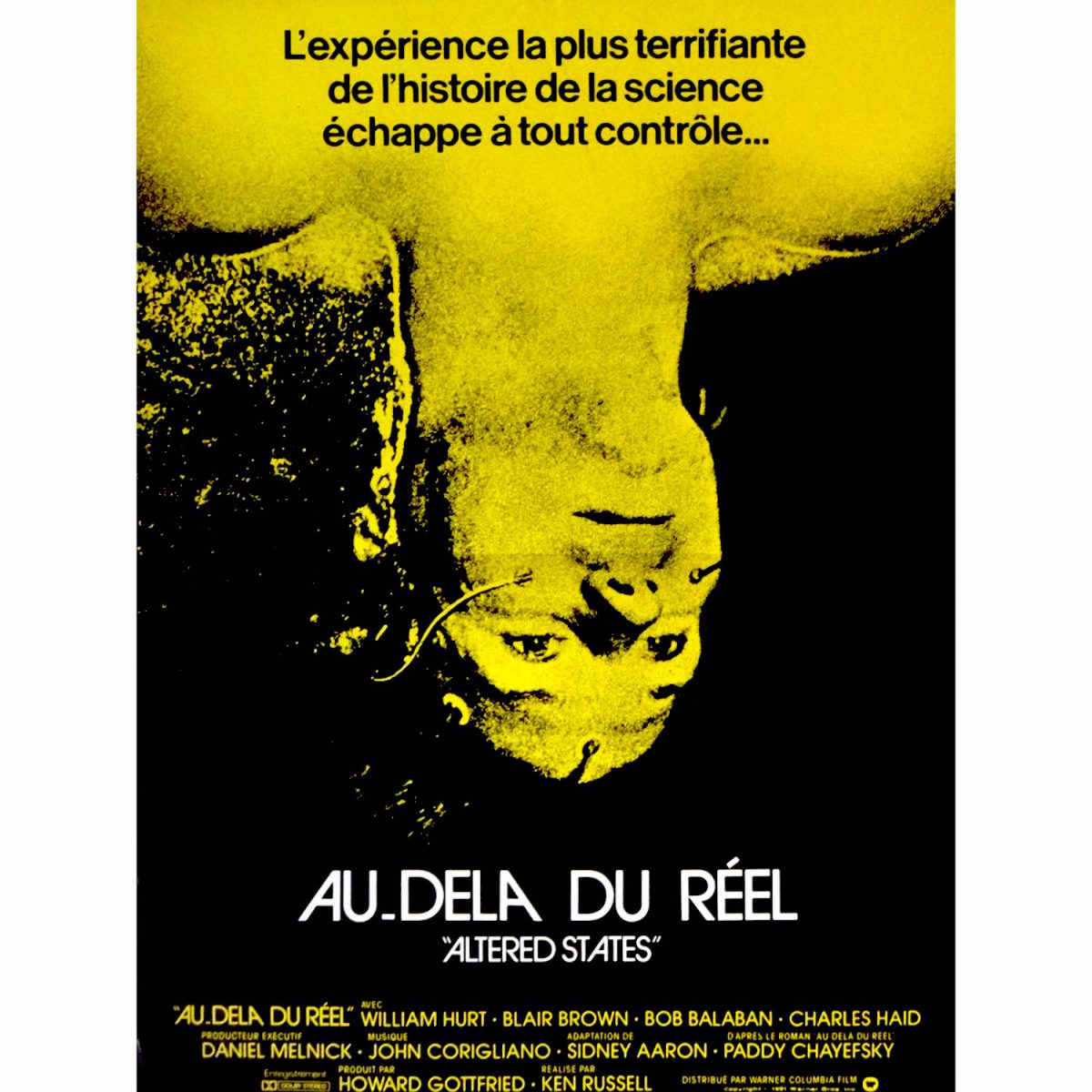

Chayefsky noticed how he changed from quiet bookish nerd to pork-eating loud-mouth braggart. Like all writers (Mailer included), he saw what was happening and saw it as something to be filed away for future use. In fact nearly everything Chayefsky wrote was a vehicle for his own biography and opinions. Marty owed something to him. Dr. Herbert “Herb” Bock in Hospital riffed whole conversations Chayefsky had with his agent or his friends over pastrami, cheese and gherkin sandwiches in bustling New York deli’s. In Network, Peter Finch spouted Chayefsky’s thoughts about culture, television, and the expectations of life. It’s how Chayefsky worked. Then one day, three Oscars in the bag, he thought back to his time in the army and the personality he had created to get through it all and how it had grown into this monster. He thought about this aggressive man called Paddy Chayefsky who had come from inside Sidney Aaron. He discussed the idea over lunch with his pals Bob Fosse and Herb Gardner circa 1975 in the Russian Tea Rooms. He knew there was a story here like Robert Louis Stevenson‘s Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He went home and wrote a treatment which came together like nothing he had ever written before. He knew he had his next movie, his next potential Oscar-winning script. He researched his subject matter and then wrote a script about a self-important scientist who unleashed the primitive man lurking inside himself. The script was called Altered States.

Chayefsky’s currency as writer was high. He was in a position where he could have submitted his laundry list and the studios would have seriously considered its potential as a movie. But this script was difficult. While it garnered considerable interest it was thought to be filled with too much psychobabble which the studio heads could not quite understand and some found (frankly) embarrassing.

I’m a man in search of his true self. How archetypically American can you get? Everybody’s looking for their true selves. We’re all trying to fulfill ourselves, understand ourselves, get in touch with ourselves, face the reality of ourselves, explore ourselves, expand ourselves. Ever since we dispensed with God, we’ve got nothing but ourselves to explain this meaningless horror of life….Well, I think that that true self, that original self, that first self is a real, mensurate, quantifiable thing, tangible and incarnate. And I’m going to find the fucker.

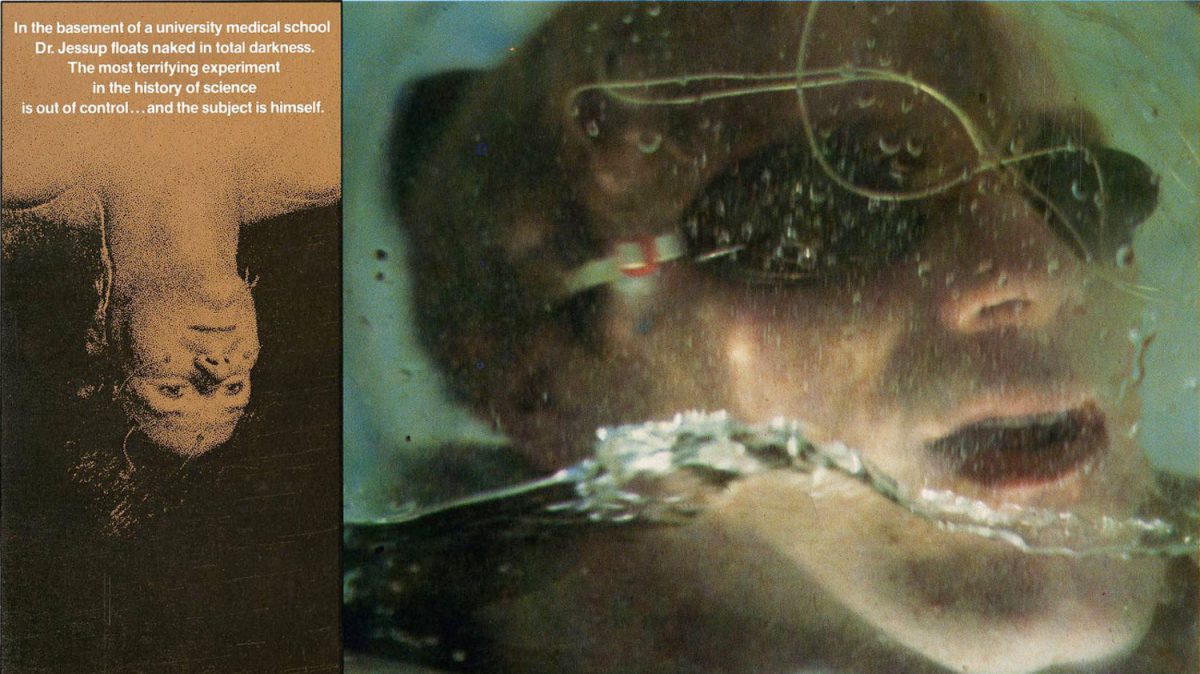

To make his movie more bankable, it was suggested Chayefsky should write a book based on his screenplay. Chayefsky reluctantly agreed. The strain of writing this book and the angst of trying to get the film made caused Chayefsky to have a heart attack before the last chapter was finished.

The novel Altered States was published in 1978. It received mixed reviews but very good sales. Now Chayefsky had the double whammy of a best-selling book and a script. Despite some reservations over the screenplay’s reliance on preposterous technical jargon, Chayefsky’s project was given a green light. Arthur Penn was signed to direct but after six months of squabbles or rather “artistic disagreements” with Chayefsky, Penn walked.

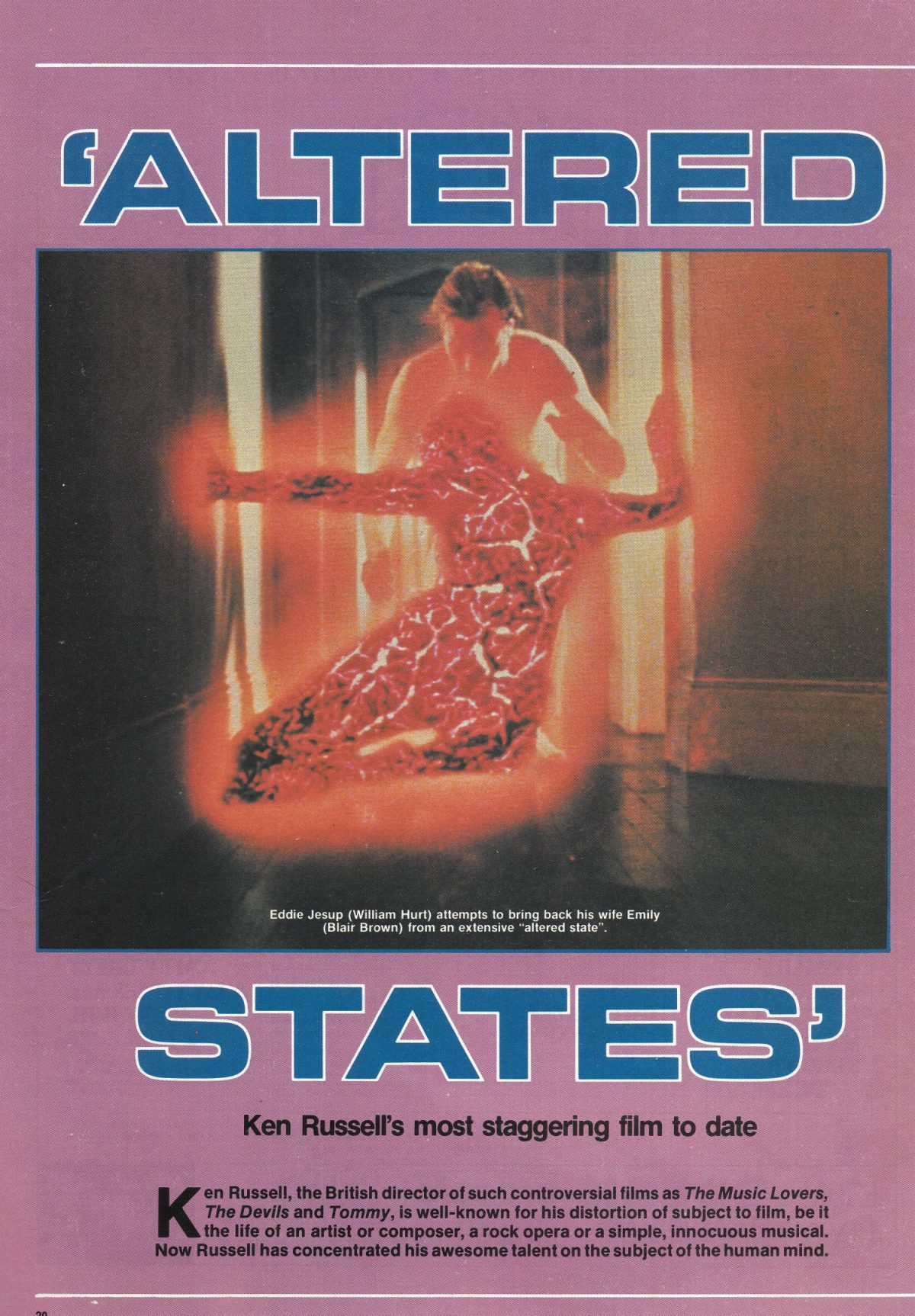

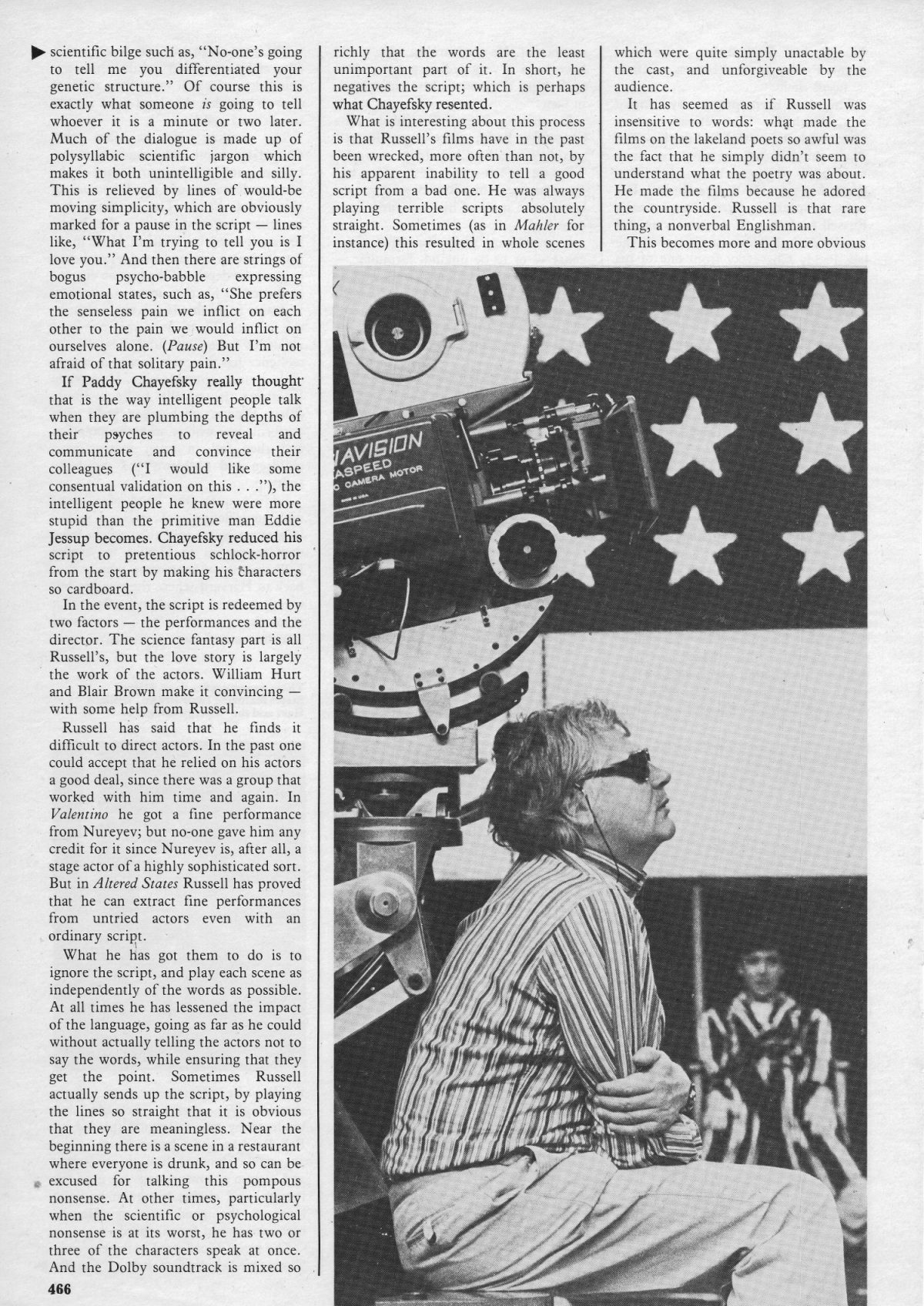

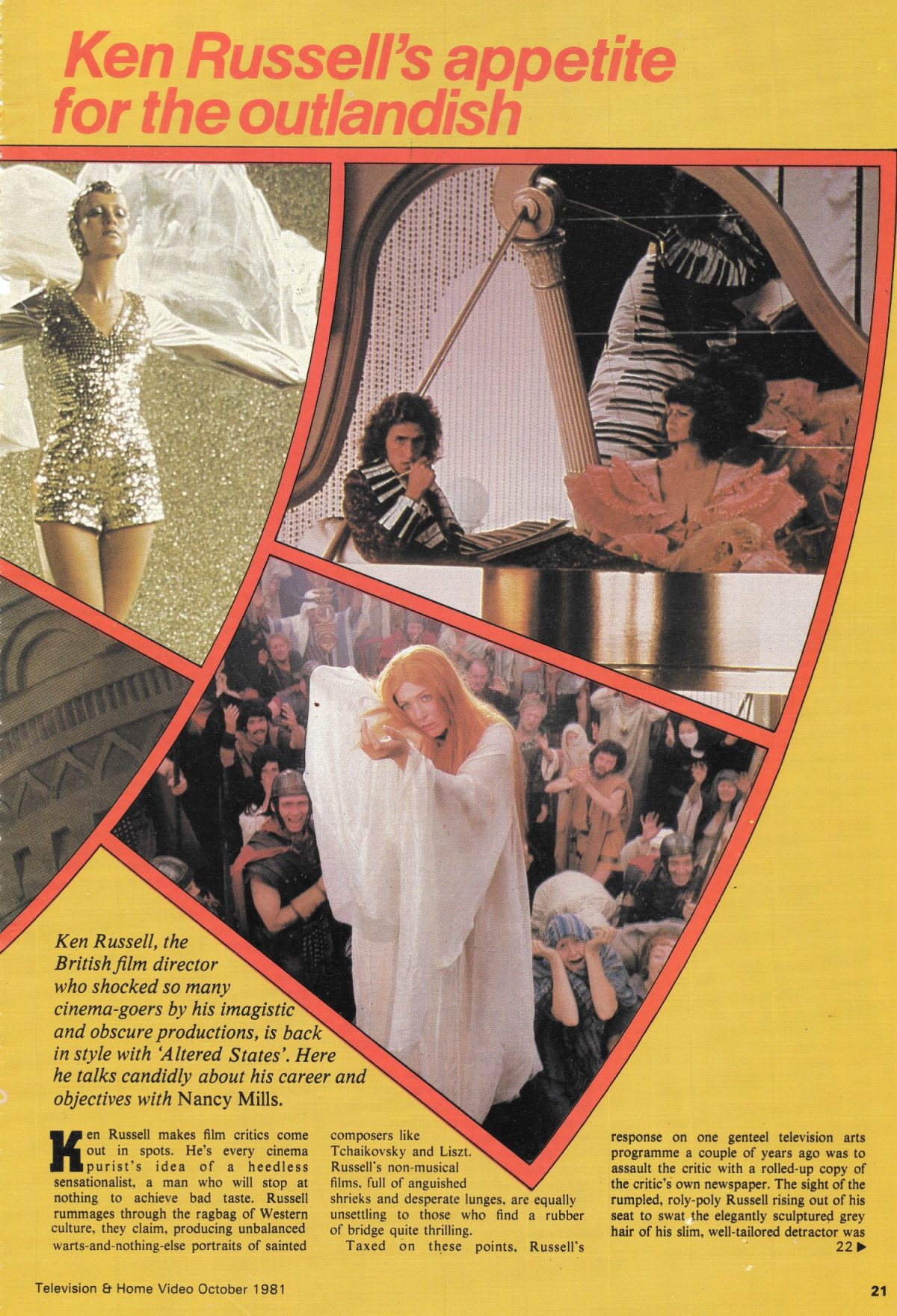

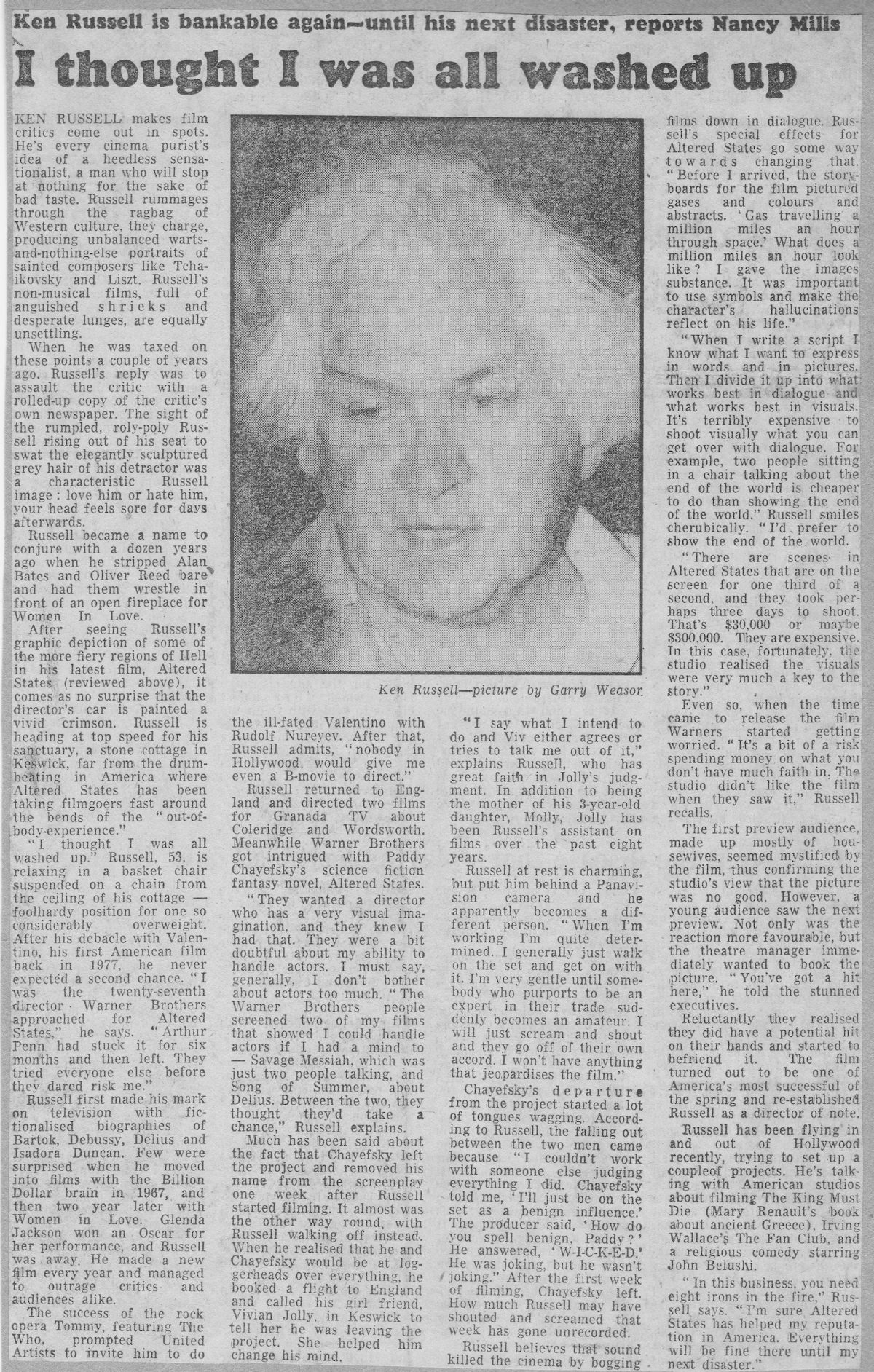

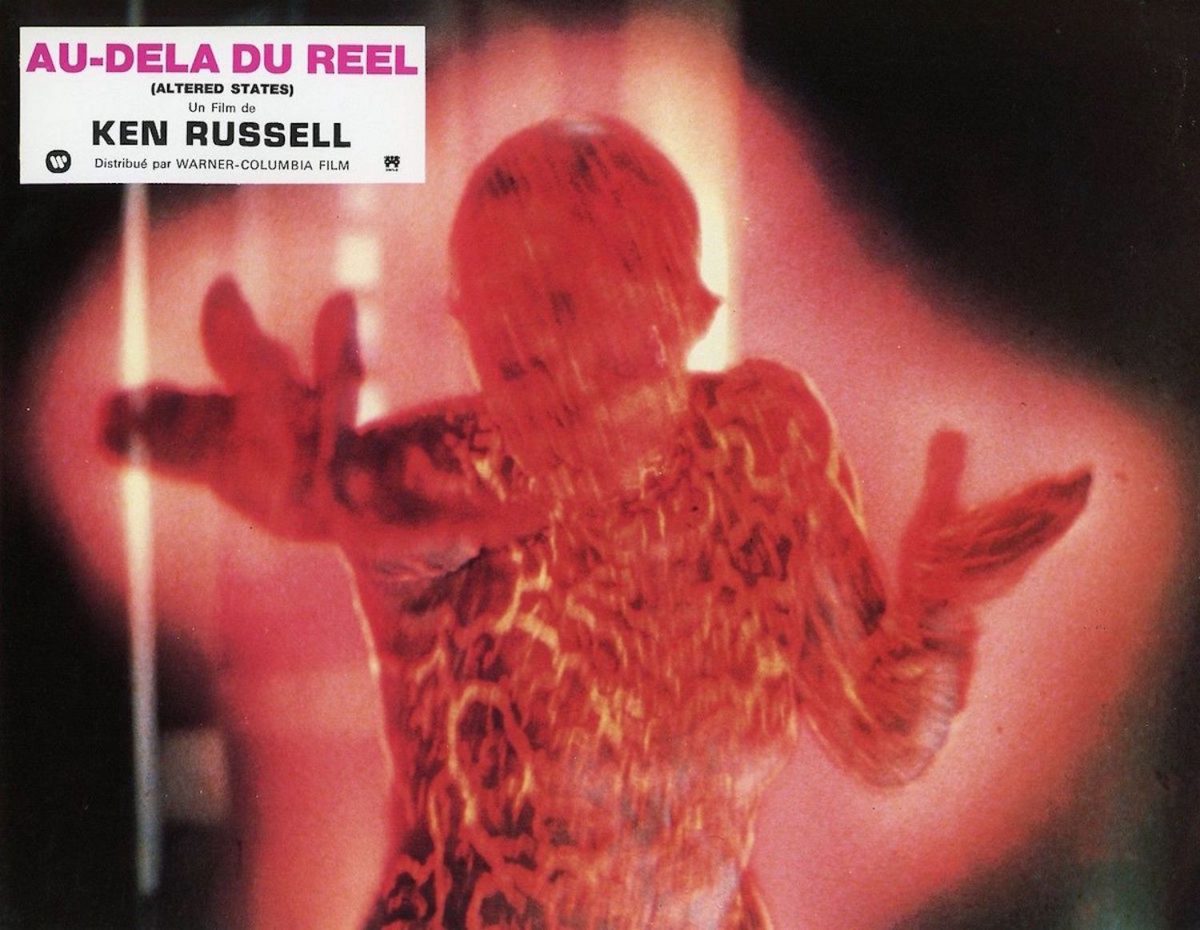

There followed another 26 directors before, almost as a last resort, Ken Russell was asked to direct. Chayefsky thought he had a malleable director who would do his bidding and submit to his Word. But Russell was a non verbal director who operated on image not text. Chayefsky was about to meet his match.

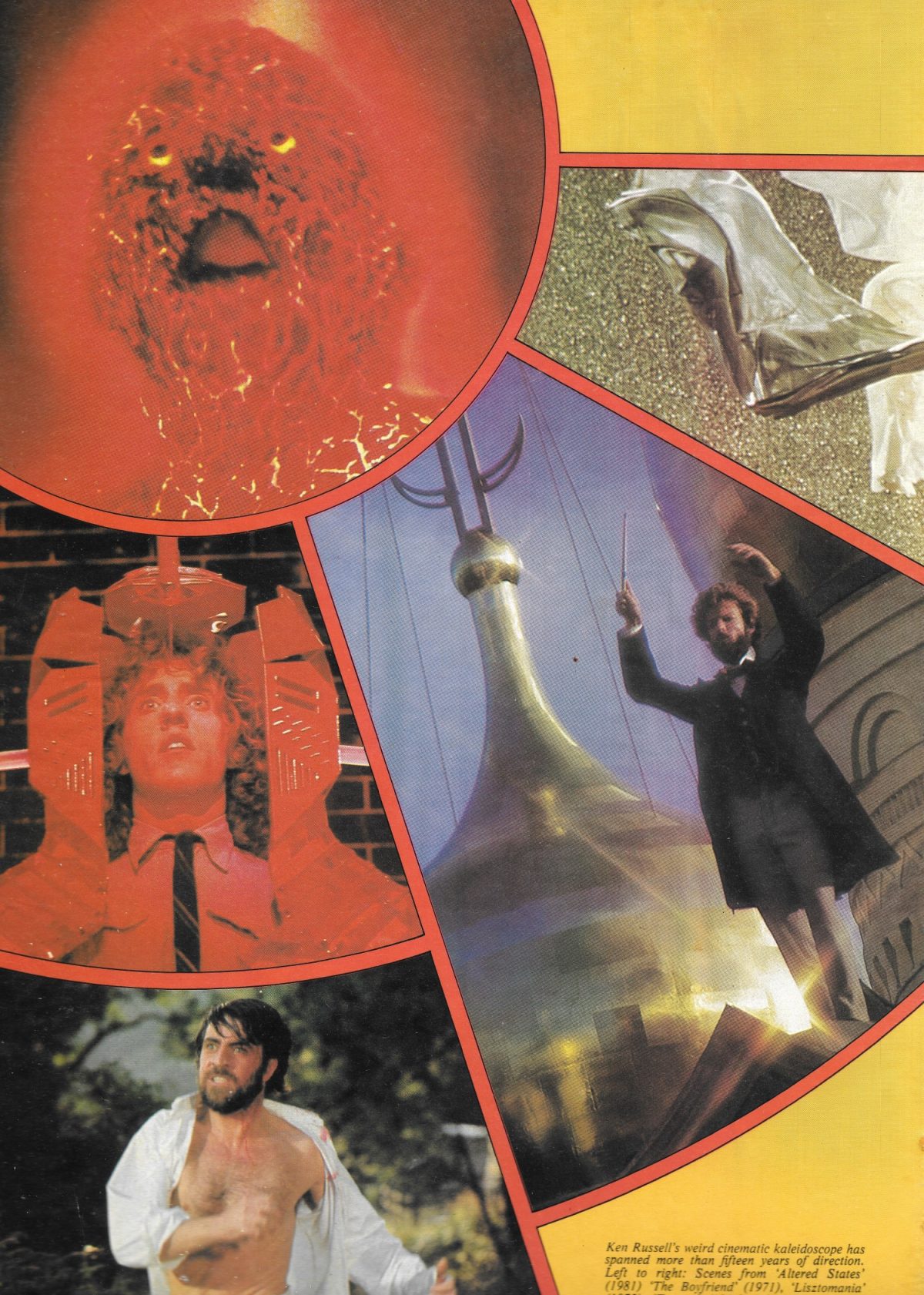

Ken Russell thought he was all washed up when he was asked to direct Altered States. Until then, nobody in Hollywood would have given him a B-movie to helm. He hadn’t made a movie in four years since he directed Rudolf Nureyev and Michelle Phillips in Valentino. Though not as bad a movie as either Russell or his critics thought, Valentino almost destroyed the great director’s career. He thought this film, the worst of his career and had (foolishly, he claimed) turned down directing The Rose starring Bette Midler and his favourite actor Alan Bates.

Then along came Altered States as Russell told Nancy Mills in 1981:

I was the twenty-seventh director Warner Brothers approached for Altered States. Arthur Penn had stuck it for six months and then left. They tried everyone else before they dared risk me.

They wanted a director who has a very visual imagination, and they knew I had that. They were a bit doubtful about my ability to handle actors. I must say, I don’t bother about actors too much. The Warner Brothers people screened two of my films that showed I could handle actors if I had a mind to – Savage Messiah, which was just two people talking, and Song of Summer about Delius. Between the two, they thought they’d take a chance.

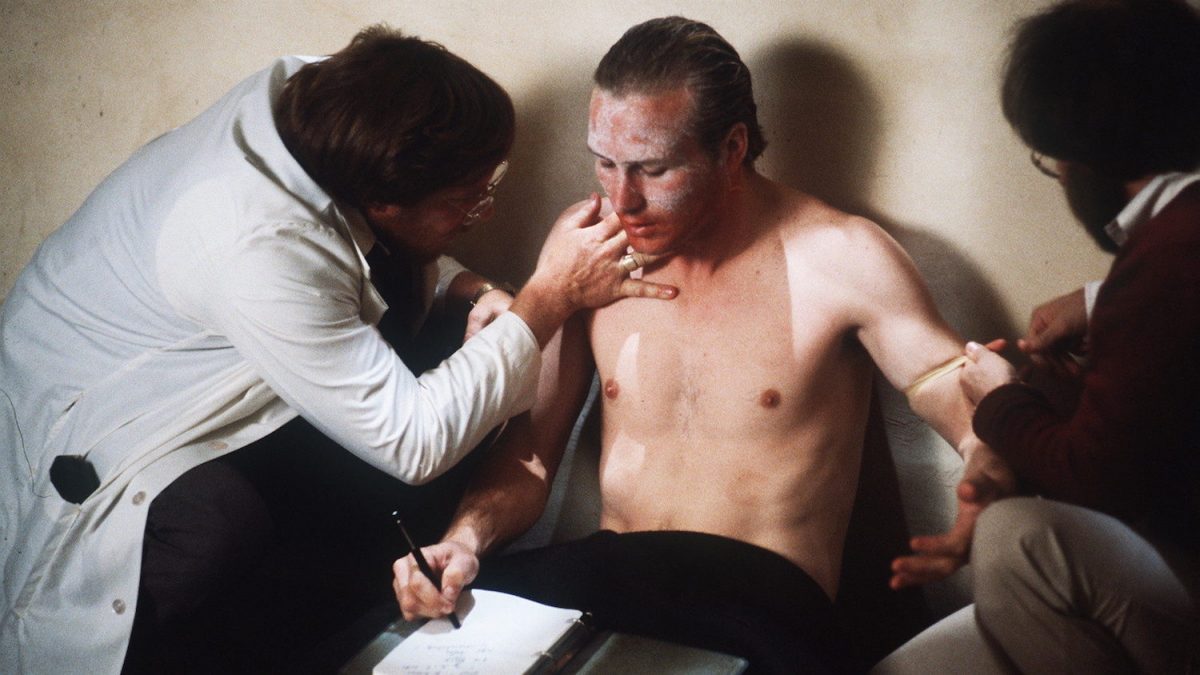

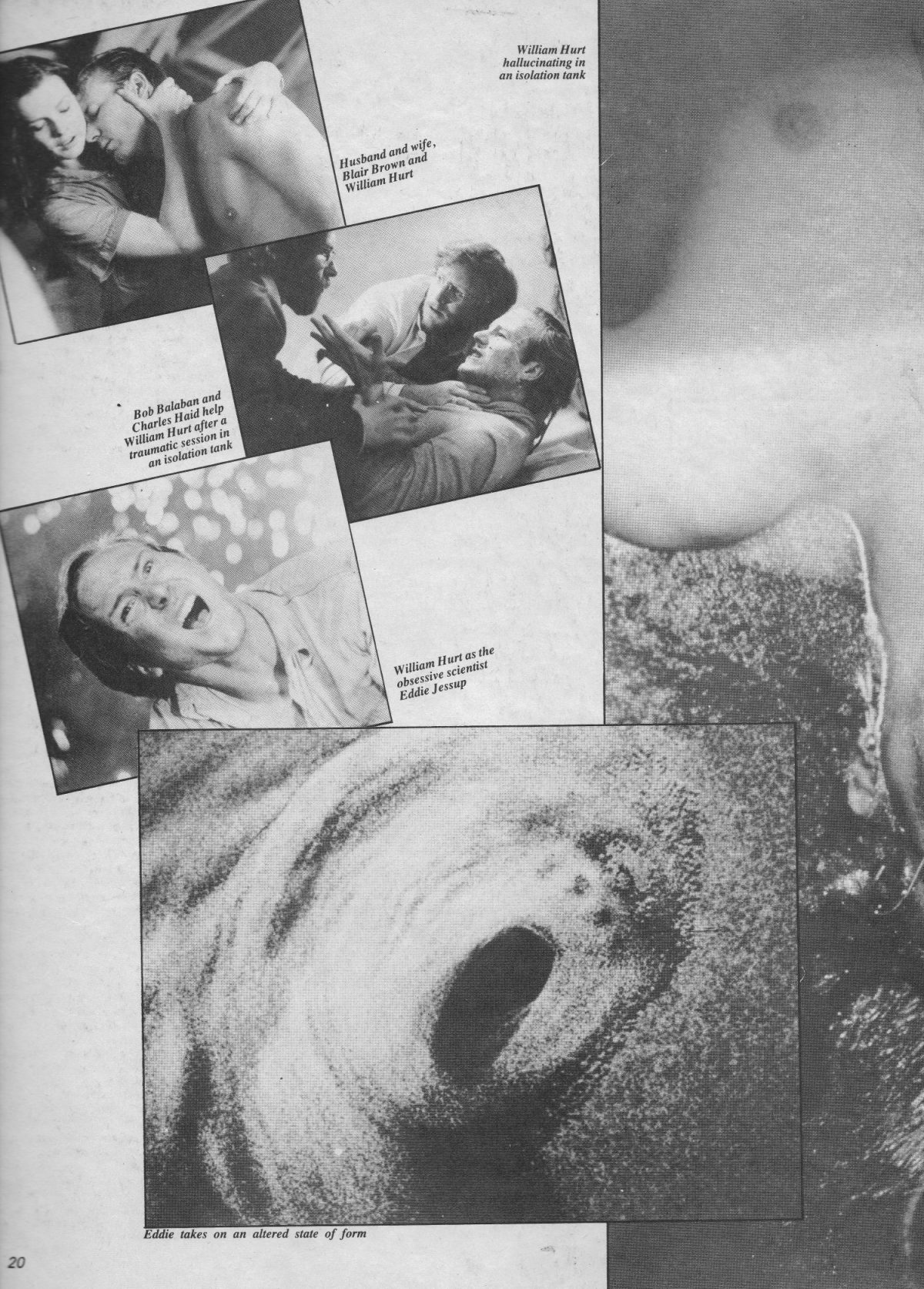

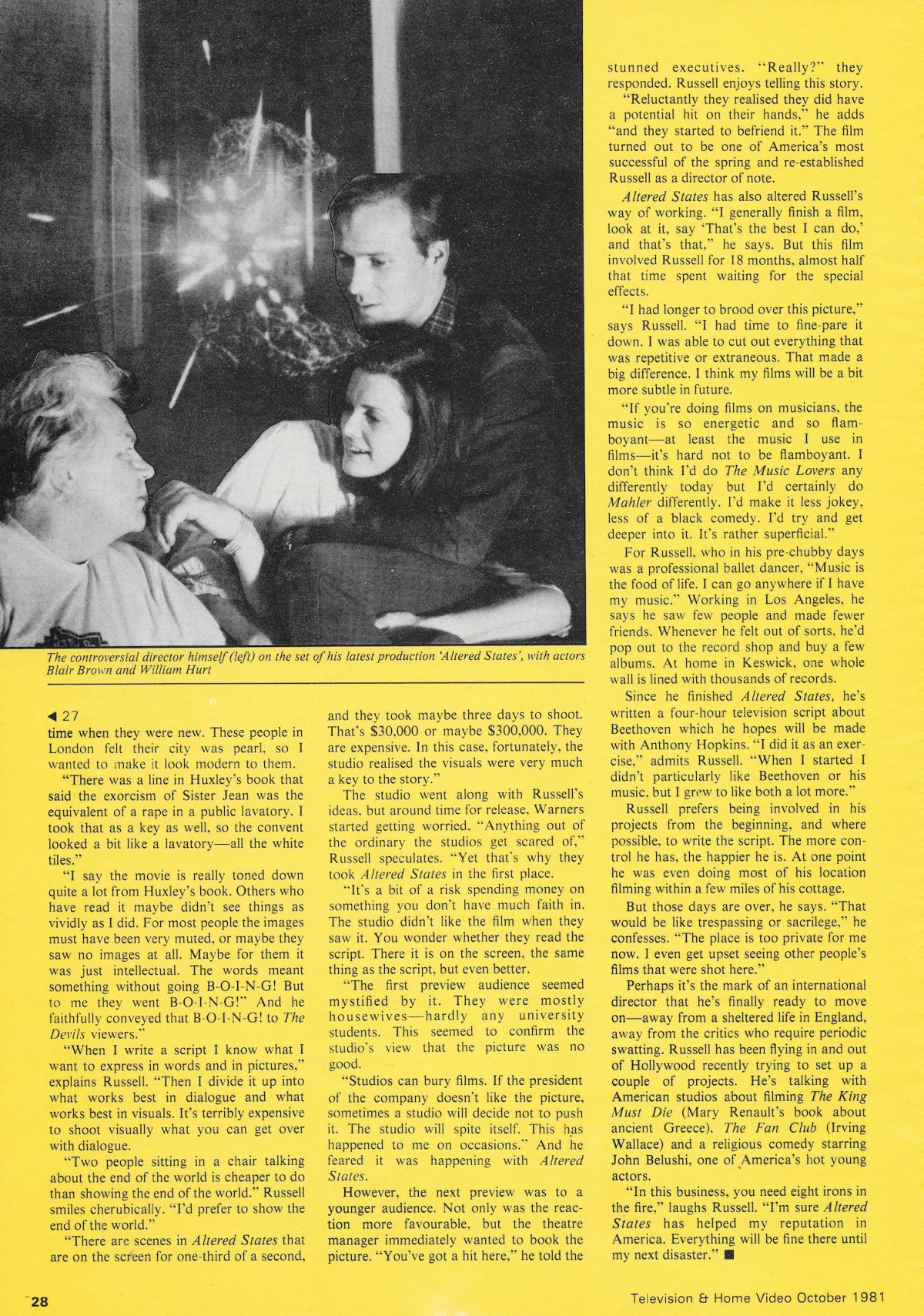

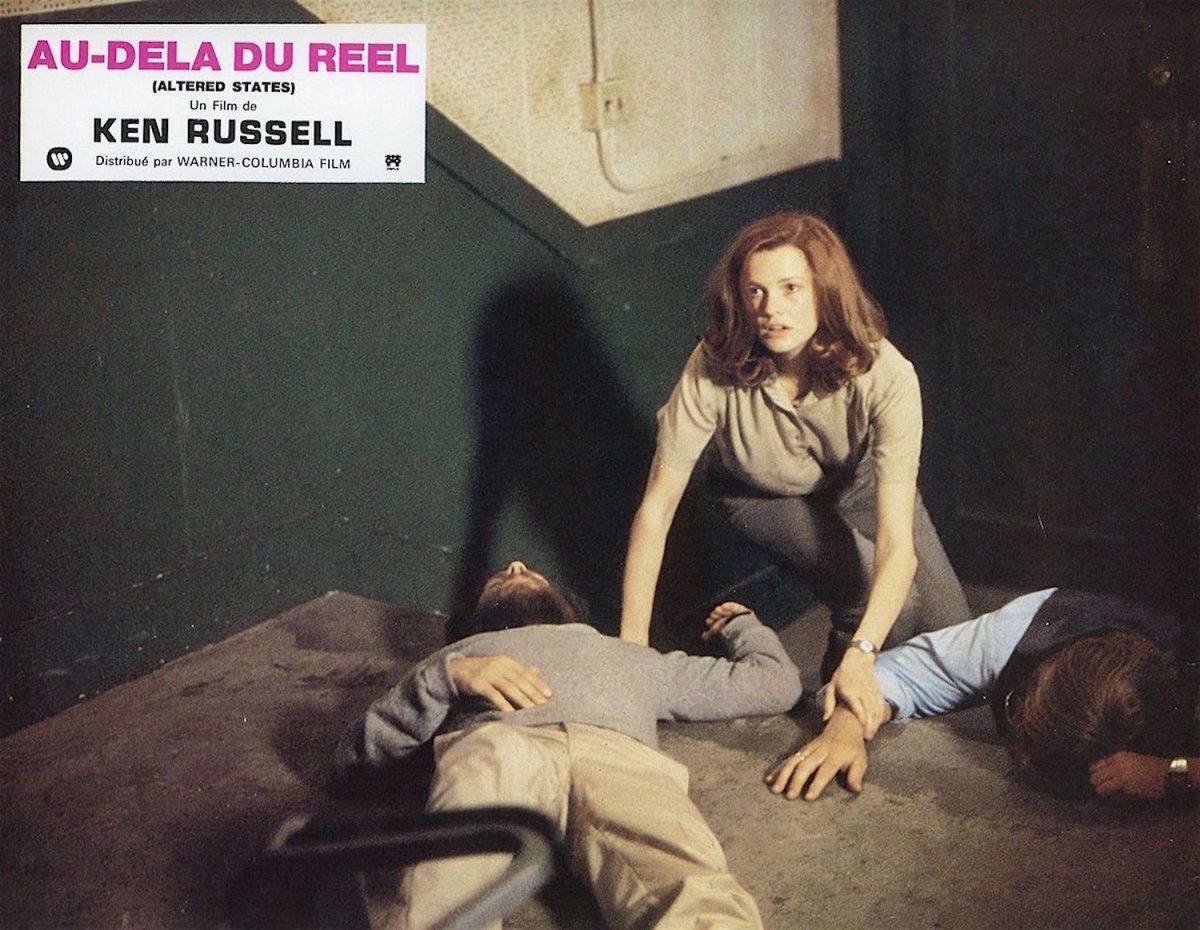

Once on board, Russell realised the difficulties he would face in working with Chayefsky. He didn’t like the script but faced the problem of being unable to cut, alter, or change one word of Chayefsky’s script by having the actors William Hurt, Blair Brown, Charles Haid and Bob Balaban speak their lines quickly or mumble them between large mouthfuls of food.

Chayefsky complained “He’s ruining my script.” Russell was intransigent. There could only be one person in charge of making this film, and that person was Ken Russell. He treated Chayefsky badly, dismissing his complaints or undermining him with sarcasm:

You can’t improve on perfection, Paddy. Why don’t we rehearse the scene where Jessup [Hurt] fucks Emily [Brown] on the kitchen floor? I’d appreciate your input on the grunts.

According to producer Howard Gottfried, Russell “would make real lousy remarks, Just anything to get Paddy upset. He was really looking to dislodge Paddy from any position of authority, that was obvious. He more than baited Paddy. He wanted to debase him, to irritate him.”

By the time the principal photography began, Russell had the upper hand and he and Chayefsky were no longer talking.

Chayefsky wrote a friend that he was out in Hollywood making a movie with a director who had turned out to be “a monster…a monster with not enough talent to make it worthwhile.” He was tired and the constant battling with Russell made him realise that the Word was not enough.

Things came to a head one night over the telephone when Russell told Chayefsky:

Why don’t you take your turkey sandwiches and your script and your Sanka and stuff it up your arse and get the next fucking plane back to New York and let me get on with the fucking film.

In the short story “Cain” by Amelia B. Edwards, a young man becomes obsessed by a painting “Cain after the murder of Abel” by Camille Prevost. Edwards was all too aware of the dangerous magic of the image over the power of the Word:

When I went out, the sunshine of the summer afternoon offended my eyes. I chose a shady avenue, and there paced to and fro, thinking of the picture. Evening came, and it still haunted me, I strove to shake off the weird influence. I stepped into one of the theatres–but the laughter, the music, the lights were alike insupportable to me. Then I went home to my books, but could not read–to bed, but sleep forsook my pillow.

…

From this moment, the picture began to exercise a strange, mysterious influence upon my whole being. I dreaded it, yet could not tear myself from it.

Before the Word there was the hieroglyph. An image, an emoji that encapsulated more information succinctly than any series of well-constructed sentences ever could.

Ken Russell knew this. Perhaps Paddy Chayefsky didn’t.

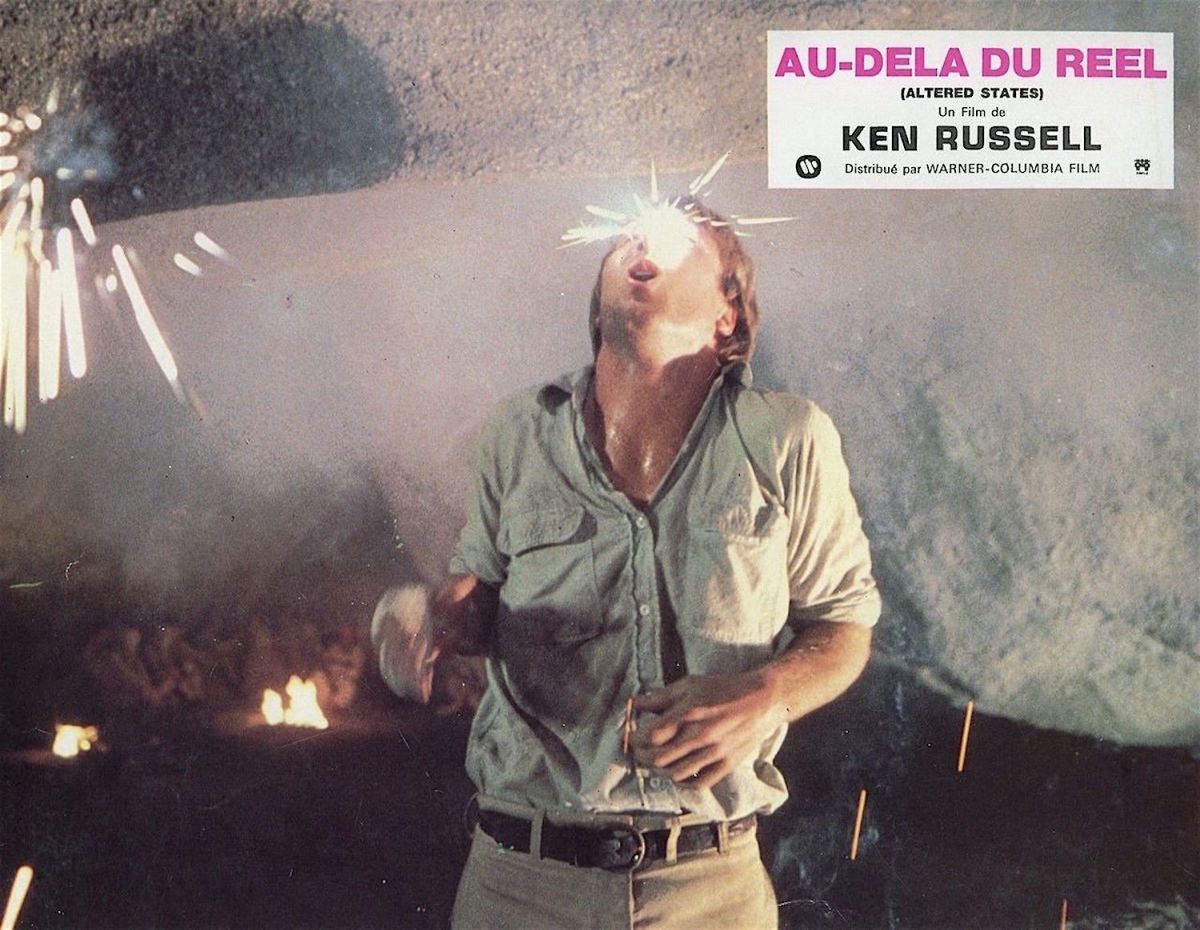

The battle with Chayefsky had tired and distracted Russell. As a source of inspiration for the movie’s visual sequences, he tried a few magic mushrooms by the pool at his Hollywood home. It gave him a bad trip.

The extensive garden, which until now had seemed akin to a tropical paradise, began to assume a disturbing malevolence. The plants and the trees…took on a positively threatening air, more animalistic than botanic. The waving palm leaves were savage claws ready to tear our flesh. Wherever we looked there was no escape….We were surrounded by cruel, green talons, the bared fangs of vicious razor-sharp leaves and snaking tendrils lashing at our bare bodies.

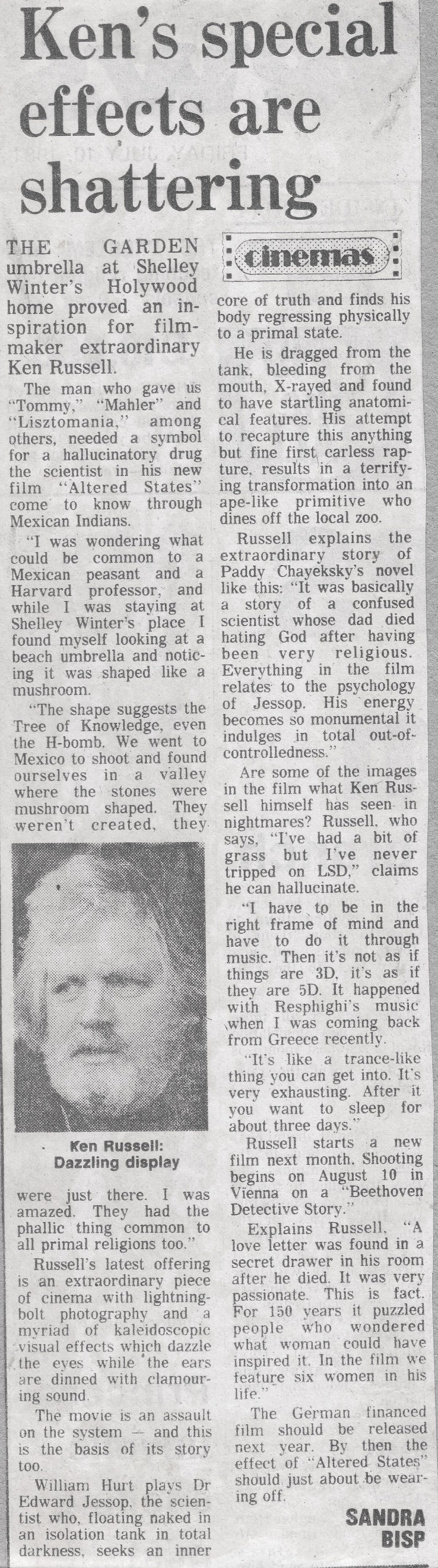

Later, Russell smoked some weed under a parasol at Shelley Winter’s house. It was then that he saw the first of the symbols he would use in his film.

I was sitting in my garden in Los Angeles, thinking for hours, and I found myself gazing at an umbrella. And that’s actually how I made the connection between the mushroom and the tree of knowledge…We had a man, a woman, and a tree painted on the wall of a cave. The mushroom, the rocks shaped like mushrooms, the atomic mushroom cloud.

The movie’s unforgettable imagery owes as much to Russell tripping in the Hollywood Hills as it does to his (lapsed) Catholic beliefs. Adam and Eve, the crucified Christ, the many-eyed goat, and the power of redemption. Russell made Altered States not so much about Chayefsky’s Jekyll and Hyde nature but as a story about the redemptive nature of love.

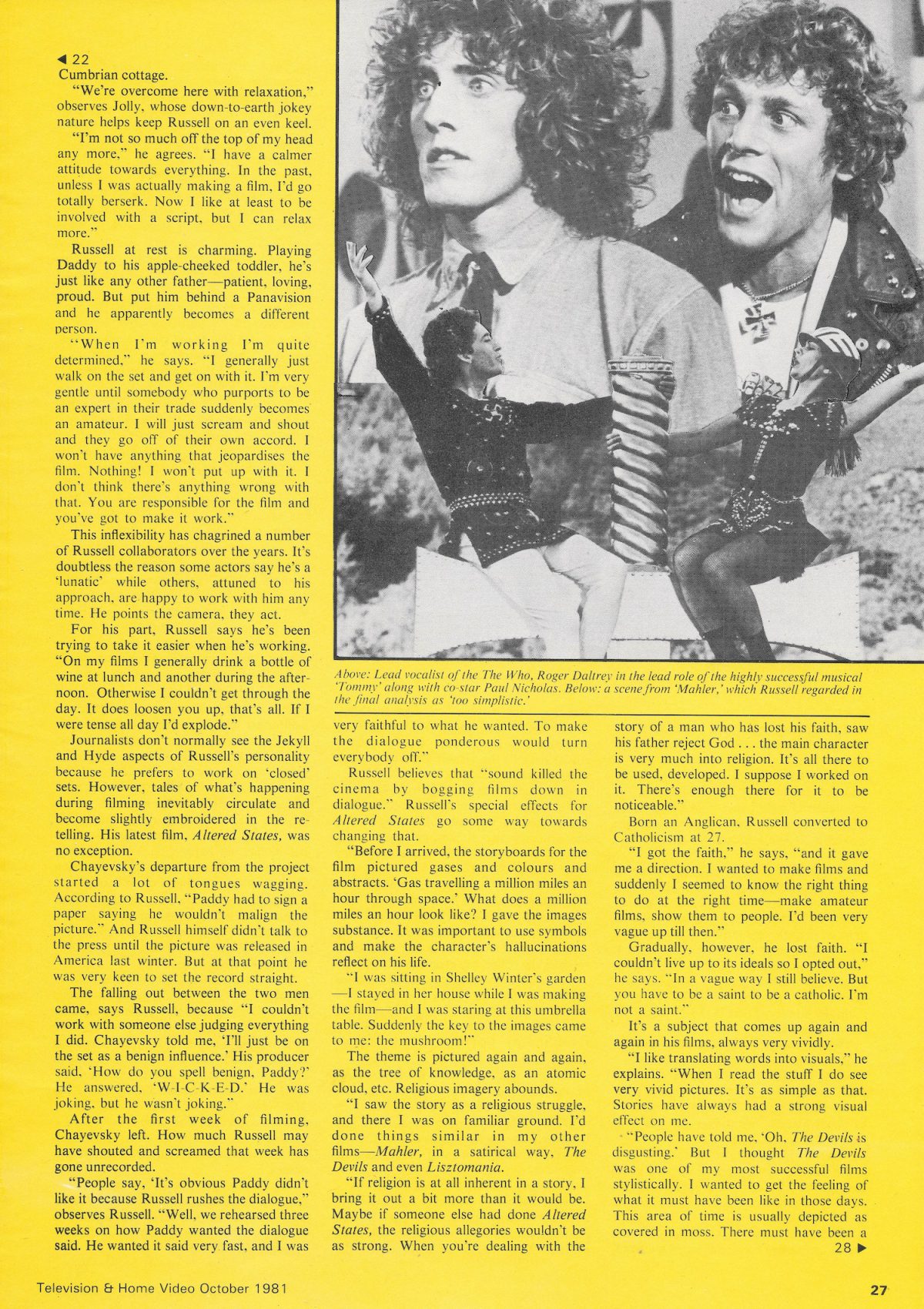

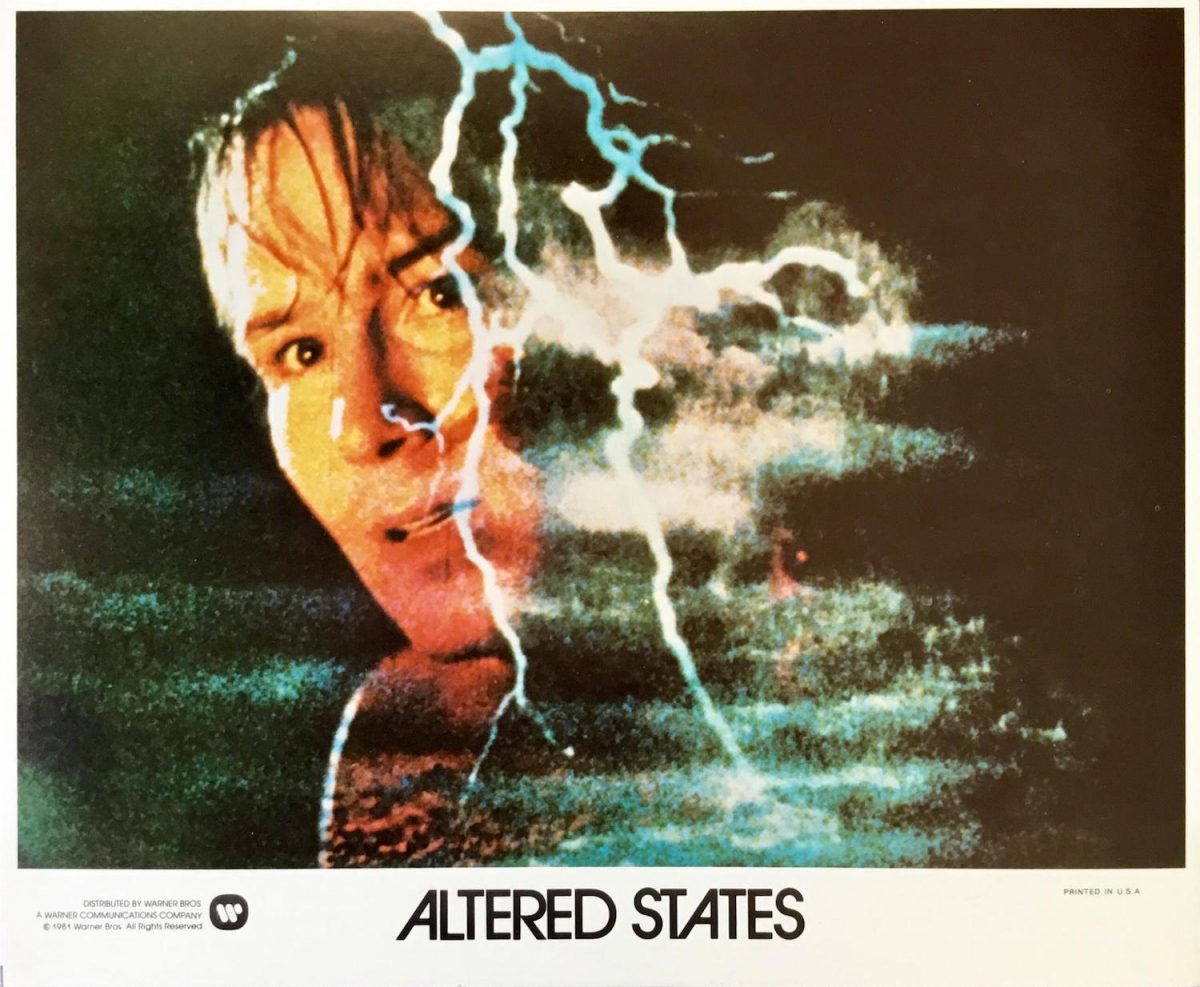

When Altered States was released in December 1980, it received fair to positive reviews–Time voted it one of the ten best movies of the year. It was a box office hit, especially with the youth audience, as Russell claimed:

Many of the kids went back time and again for the hallucinations alone–sitting in the foyer between trips, getting high, while a lookout was bribed to stay in the auditorium, enduring the dialogue until it was time to poke his head around the door and shout ‘next hallucination!’

As for Chayefsky, he never quite recovered from making Altered States. He disowned the movie and had his screen credit changed to his birth name Sidney Aaron. Chayefsky died ten months after the film’s release on 1st August, 1981. His last words, written to his wife were:

I tried. I really tried.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.