AS impossible as it is for me to believe, Glen Larson’s version of Buck Rogers in the 25thCentury (1979 – 1981) turns thirty-five years old this year.

Today, this cult-TV series is often remembered for its spandex fashions, its gorgeous female stars and guest stars, its penis-headed robot Twiki (Felix Silla/Mel Blanc), and its oppressive re-use of familiar or “stock” visual effects in the space dogfights.

Though Buck Rogers in the 25th Century had its weak installments, for certain (like the dreadful “Space Rockers”) it was also a light science fiction series — a romp, essentially — and the series is recalled fondly by fans on those terms too.

Yet in remembering the series, one can detect that the best episodes — or at least the ones that best hold up today — are those that concern relevant cultural issues, or base their narratives in literary or mythic antecedents.

Below, are my selections for the five best episodes of this space series, which ran for two seasons on NBC, and from 1979 to 1981.

“The Guardians”

In this second season show, Buck (Gil Gerard) and his new friend Hawk (Thom Christopher) investigate a long unexplored world. Although the exploration of the planet is “strictly routine” Buck and Hawk soon encounter Janovus XXVI, an old man on his death bed.

This ancient “Guardian” informs Buck that he has been waiting for him for over five hundred years. Now, he must pass on to Buck, “The Chosen One,” an ancient green box. This jade artifact must be transported to the old man’s unnamed successor and only a person who is of both “the past and the present” can get it to its destination successfully.

Although reluctantly, Buck undertakes the task. Soon, however, the crew of the Searcher begins to experience strange dreams and visions, ones ostensibly caused by this unique box. Admiral Asimov (Jay Garner) dreams of his crew starving to death in the loneliness of space, while Wilma Deering (Erin Gray) imagines herself a blind outcast, wandering the hallways of the Searcher alone…

As I noted above, Buck Rogers is a pretty light show, a fact which distinguishes it from Glen Larson’s other outer space series: Battlestar Galactica (1978-1979). There’s often a great deal of humor on Buck, and a tremendous amount of physical action too. In some sense, “The Guardian” showcases how the series could have approached more serious sci-fi storytelling had the producers selected that path.

Here, the visions of beloved characters starving to death or going blind are authentically disturbing. I remember watching the program for the first time in 1981 (at age 11) and feeling pretty jolted by Asimov’s phantasm of a crew dying from hunger. This moment resonates, and is probably the strongest imagery in the episode.

The writing for the main characters here is also some of the best in the series’ second season. We learn how heavily Asimov carries the burden of command, we come to understand Wilma’s fear of appearing vulnerable or being pitied. And we are reminded once more of Hawk’s utter isolation and alone-ness as he experiences a return visit from his dead mate, Koori (Barbara Luna).

Importantly, there is also a literary or mythological underpinning to “The Guardians.” This is the story, essentially, of Pandora’s Box. The jade box, once opened, creates terror and pain everywhere it is taken…

“Awakening”

This two-hour pilot episode was released theatrically in March of 1979, and actually received strong reviews from a number of tough-minded critics of the day (including Vincent Canby), if that says anything of the episode’s quality.

In this story, we meet Buck as he is awakened — a man out of time — in the 25th century, and forced to contend both with Draconian treachery and the fact that all of his loved ones from the twentieth century are long gone….dead in a nuclear holocaust.

The underlying precept of this episode is a little crazy. It’s American Exceptionalism in space, essentially, as Buck proves he is the only man who can save the Earth from its own unfortunate dependence on computers and logic. Yet Buck — the avatar for emotion and instincts – hails from a time, the holocaust, that destroyed the world. It is incoherent indeed, to say that the hope for man’s future hails from an era of global self-destruction.

Yet the film gets away with its contradictions because it plays effectively like a James Bond in space, or in the future. We all know that James Bond is irresistible to all women, best in a fight or shoot-out, and supreme exemplar of style and taste. Nobody does it better, right? Here, Buck Rogers seems to have the same magic touch. We accept the premise, in short, because we recognize it from that other popular franchise.

Despite such flaws, “Awakening” vets an intriguing premise involving the Draconian “stealth” attack (a kind of Trojan Horse in Space dynamic), and features at least one authentically great sequence set in Anarchia, or “Old Chicago.” Here, Buck goes in search of his past, and finds it…in a grave-yard.

This scene in Anarchia is particularly well-shot, acted, and scored, and adds a significant human dimension to the film’s tapestry. It reminds us that Buck has lost everything. Not just his family…but his entire world. There were many stories to be vetted in Anarchia, but in its two-year run, Buck never returned there, and that’s a shame.

“The Satyr”

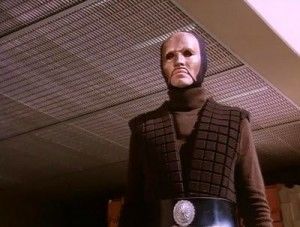

In Buck Rogers’ “The Satyr,” Buck explores the planet Arcanus, the site of a failed Earth colony while the Searcher is away for ten days on a mission to “sweep” an asteroid belt. On the planet surface, Buck soon meets Cyra (Anne E. Curry) and her son, Delph (Bobby Lane), the only settlers who have remained behind on the planet.

Buck soon discovers that the duo is regularly harassed by Pangor (Dave Cass), a half-man/half-goat creature. Buck battles the violent Pangor, but is bitten by the satyr…

As some critics and fans have duly and accurately noted, “The Satyr” is actually a thinly veiled story about alcoholism and domestic abuse. And again, this is not the typically “light” topic of the series.

In “The Satyr,” Cyra and Delph live a relatively happy life, until Dad – Pangor – shows up at their home, demanding wine and violently threatening Mom.

In one scene, the audiences watches alongside Delph through an exterior window as, inside the home, Pangor pushes Cyra onto her back (behind the kitchen table), and threatens her with physical violence. He wants more wine even though, as Cyra tells him, “he drank it all the last time.” The subtext here isn’t just violence, but sexual violence, at least in terms of the scene’s blocking.

What we also see in “The Satyr” — particularly in this camera view from the outside-in — is the notion of a child dwelling in a terrifying household of alcoholism and domestic violence, and seeing things that no child should.

“The Satyr” also grows unpredictable when Buck actually grows sick with “the virus “and loses his long-held status as the white knight. Too often in the series, Buck was always right, always lecturing others about his values. Here, he gets to lose control a little, and it’s a nice stretch for both the character and the actor who portrays him.

“Space Vampire”

In “Space Vampire,” Buck and Wilma drop-off Twiki for repairs at Theta Station and witness a derelict star-liner collide with the station.

The atmosphere of Theta is contaminated, and the logs of the derelict — the I.S. Demeter – suggest the crew and passengers were suffering from hallucinations brought on by the Denebian virus called EL7.

But the station’s medical officer, Dr Ecbar (Lincoln Kilpatrick) reveals to Buck that the crew of Demeter is not dead, only drained of “spirit,”

Buck suspects a being, not a disease, is the culprit, and he’s right. The evil Vorvon (Nicholas Hormann) creates un-dead minions out of the station crew. He then prepares to make Wilma Deering his immortal bride.

If you tally-up all the narrative’s details, this episode of Buck Rogers is a dedicated adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, right down to an epistolary structure.

To wit, the literary Dracula was crafted in the form of letters, newspaper clippings, Mina’s Diary, Seward’s phonograph recordings, and Jonathan Harker’s journal. Buck Rogers; “space age” corollary for Stoker’s literary approach involves the captain’s log from the Demeter, the servo drone recordings of a Demeter passenger from “New London” named Helson (Van Helsing??), and even helpful communiques from Dr. Huer (Tim O’Connor) and Dr. Theopolis on Earth.

The other parallels to Dracula are more obvious but no less enjoyable. The only object to ward off the Vorvon is an “ancient power lock,” the “25th century equivalent of a cross,” in Buck’s words. And like Dracula, the Vorvon can also mesmerize his victims and change forms at will. Just as Dracula could turn to mist, wolf or bat, the Vorvon here often takes the shape of a red, pulsating energy blob. The name of the derelict ship, the Demeter, itself originates from Stoker’s novel and serves the same purpose in both texts: carrying the “disease” (Dracula or Vorvon) to civilization.

Beyond all these tributes to Stoker’s there’s a strong sense of inevitability and dread in “Space Vampire.” The Vorvon pursues Wilma relentlessly and eventually gets her, and the episode, though silly and campy at spots, succeeds in being strangely terrifying.

“The Plot to Kill a City”

This story opens with Buck on a secret mission to replace a legendary criminal named Raphael Argus. Argus is a member of “The Legion of Death,” a terrorist group planning to deliver “final retribution” on New Chicago (a city of 10 million people…) for the death of a comrade.

Because Buck hails from the 20th century, there’s no record of his existence in the data-heavy, computerized 25th Century, and so Dr. Huer sends Buck to infiltrate the Legion and learn its secret plan. Since the Legion of Death members rarely gather – and don’t know each other by sight – this seems an ideal strategy.

Not so fast, however, as Buck is pitted against a team of James Bond-worthy villains. He battles a soldier villain, Varek (Anthony James), a general villain, Kellogg (Frank Gorshin) and two twisted hench-people, Quince (John Quade) a heavy gravity assassin, and Sherese (Nancy De Carl), a paranoid empath whose powers put Counselor Troi to shame. Lastly, there’s a villain who can’t feel pain, martial arts expert Markos.

So Buck is not only outnumbered this time, but his finely-honed human instincts are challenged by those with paranormal, superhuman capabilities.

Yet the dynamic conflict is not the heart of this finely-written show. Instead, we learn that Varek originates from a planet that survived a “nuclear war, only to face a future of terrible genetic deformity. Varek hides his misshapen face behind a golden mask so as not to reveal his hideous visage. He speaks meaningfully to Buck about what the apocalypse did his planet’s future, its children. “You can’t imagine life on my planet,” he explains. “Children afraid to look at their own reflections. Children with the touch of death.”

When “The Plot to Kill a City” aired America was still locked in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. The specter of nuclear annihilation was always present, and this episode of Buck Rogers expresses the terrible horror of nuclear Armageddon, with children paying the consequences for a disagreement over political ideology.

Even more so, the impressive two-part episodes suggests that those who use such weapons to conquer others deserve themselves to be subjugated and enslaved. That’s Varek’s plight.

This was a very strong statement for any series to make in the year leading up to Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan, and the American boycott of the 1980 summer Olympics.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.