In 2016, the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966 – 1969), a TV series and cultural phenomenon that has spawned cartoons, comic-books, films, live-action spin-offs and more toys than you can shake a tribble at.

The original series episodes have been updated to feature modern CGI special effects too, in a bid to make the series seem more contemporary, but the effort was largely unnecessary because the storytelling on the program remains so vibrant and cerebral, even half-a-century after first broadcast.

Many episodes of Star Trek are considered classics because of their importance to the franchise. “Space Seed” introduced Khan (Ricardo Montalban), for example. Some episodes reveal new shades of the beloved characters, and engender empathy for them (“City on the Edge of Forever,” “This Side of Paradise,” “All Our Yesterdays.”) Others involve events important to the galaxy itself (“Errand of Mercy,” “The Doomsday Machine.”)

But some of the seventy-nine Star Trek episodes produced simply don’t get their fair share of the sunlight. Perhaps these shows don’t possess the most memorable high-concepts of the most enduring episodes, or perhaps they are superficially similar to other, more popular segments, and thus easy to forget.

With that description in mind, here are my choices for the five most underrated Star Trek episodes.

5. “The Enterprise Incident”

The third season is generally not regarded as Original Trek’s finest hour, especially with many of the series’ more prominent historians. And yet, this span did provide a number of intriguing and memorable shows, including “The Enterprise Incident,” by D.C. Fontana.

When I interviewed the author in the year 2000, she termed “The Enterprise Incident” “a reflection of the Pueblo Incident, where a ship was captured in an area of sea where it shouldn’t have been. The ship claimed not to be a spy ship, but in fact it was a spy ship.”

On January 23, 1968, the U.S.S. Pueblo, a research vessel with seventy-six crew members aboard, was surrounded and captured by North Korean vessels. The U.S. government insisted the ship was within international waters, but the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea countered that Pueblo was inside its territory when captured. Classified, high-security material was eventually found aboard the Pueblo…so it was on an American spy mission after all. The ship was brought back to an enemy port and the Pueblo crew was tortured, and eventually returned stateside.

In “The Enterprise Incident,” many deliberate resonances of the real-life incident are plain. Here, the Enterprise strays into enemy waters, metaphorically-speaking. The Romulan Commander (Joanne Linville) plans to take the Enterprise back to a Romulan port as a prize, and process the crew before eventual release. Of course, that doesn’t happen. Instead, history is re-written rather dramatically. The party that is actually in the wrong (conducting the espionage in enemy territory in the name of intergalactic security) escapes with a secret device that could alter the balance of power.

Thus “The Enterprise Incident” is more about realpolitik than the series’ typical idealistic fare. Our heroes undertake a mission of espionage, and “win.”

But it is not a happy ending, and Spock (Leonard Nimoy) alone seems to recognize the “fleeting” nature of such strategic victories, especially in an ideological space race. He recognizes, instead, that true peace begins when two individuals from different sides share something more meaningful. He feels a connection with the Romulan Commander here, and it is not difficult to imagine that this story is the very one that led Spock to attempt peace with Romulus. Those who dislike this episode believe that it champions a kind of “might makes right” dynamic where Starfleet is always good, even when it does bad. But Spock’s involvement, and his quiet reflection on that involvement, undercuts that criticism.

4. “Spectre of the Gun”

In this episode, Captain Kirk (William Shatner) attempts to make peace with the Melkotians, a race of xenophobes.

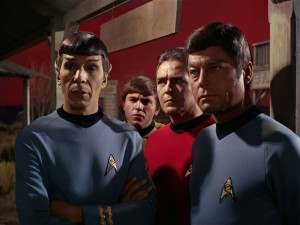

Unfortunately, the Melkotians are not at all pleased that he has ignored their warnings to stay away, and they punish Kirk and his landing party by trapping them in the world of Tombstone, Arizona, on the day of the gunfight at the OK Corral. Everyone else in this world sees Kirk, Spock, Scotty (James Doohan), Bones (DeForest Kelley) and Chekov (Walter Koenig) not as Starfleet officers, but as the criminal gang, the Clantons.

Unfortunately, history records that the Earps will kill the Clantons that very day, and this is a fate that seems inescapable until Spock is able to pierce the Melkotian illusion with the power of his mind.

“Spectre of the Gun” is disliked by some Trek scholars because they consider it a simple Western in disguise, perhaps. Or, they gaze at the unfinished sets for Tombstone — a deliberate aspect of this surreal world — and judge the episode visually cheap or slapdash.

On the contrary, however, the episode is actually one of the most visually-accomplished and stylish ventures in the entire canon. The Earps are visualized not as standard TV cowboys, but rather as soulless automatons or zombies, stuck in a “groove” that will lead them, no matter what, to kill Kirk and company. As they march, lock-step towards the OK Corral, the episode provides several expressionistic views of them, lightning flares reflected on their emotionless faces.

Similarly, the story’s overriding theme that the power of the mind beats out of the power of the gun is a terrific one in terms of Star Trek history and philosophy. The Melkotians “choose” the gunfight at OK Corral as the sight for Kirk’s execution, but this episode’s events, and Spock’s dedication to science, prove that man has evolved beyond such violence. A positive outcome can be created not through violence (as it was during the gunfight in 19th century America), but through adherence to facts, science, and logic.

Buttressed by that strong thematic line, and the daring, unnerving photography, “Spectre of the Gun” is an entertaining and thoughtful addition to the Star Trek canon.

3. “A Piece of the Action”

Star Trek appears to have become trapped in a creative rut at one point during its three-year run, sending its stalwart Starfleet crew to planets that were perfect “parallels” of societies on Earth. This was a cost-saving measure that allowed the production to re-use cheap studio settings and costumes from earlier productions. Over three years, Star Trek had a Roman episode (“Bread and Circuses,”), a Nazi episode (“Patterns of Force,”) an American Indian episode (“The Paradise Syndrome) and “A Piece of the Action,” a gangster planet episode.

A Piece of the Action” is the best of that not-great bunch, and a strong episode, however, because it concerns, under the surface, the manner in which culture is impacted when people model all their behavior on a single text or book.

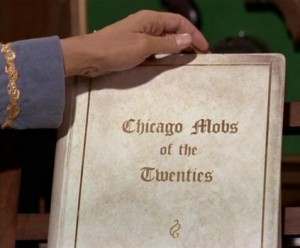

In “A Piece of the Action,” the Enterprise visits Sigma Iotia II, a planet last visited a century earlier by the starship Horizon. Alas, the Horizon left behind a book, Chicago Mobs of the 1920s, and now the people of this alien world have modeled their entire culture on gangsters like Al Capone. Hoping to undo the damage or contamination, Kirk must out-gangster the gangsters.

Funnier and smarter than the perhaps than many Star Trek comedies,” “A Piece of the Action” is actually a pretty spot-on critique of religion. In this case, Chicago Mobs of the 1920s is termed “The Book” (much like the Bible is sometimes termed the Boo, or The Good Book), and every aspect of the history book is interpreted literally. The message is clear, and cutting: base your entire society on a belief in a single book and see where it gets you.

Also, the episode, in some way, seems to predict the fish-out-of-humor of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986), with Kirk and Company attempting to drive automobiles and master the verbal intricacies of slang.

2. “Metamorphosis”

This second season story is often overlooked, perhaps because elements of it today do seem colored by the sexist attitudes of the 1960s.

And yet, despite the presence of these viewpoints, the episode “Metamorphosis” is extremely forward-looking it in terms of relationships dynamics, noting that one cannot always help who one happens to fall in love with. The episode also diagrams how non-traditional views of love can often meet with parochial, fearful attitudes when first encountered.

In “Metamorphosis” Kirk, Spock and Bones are rushing a Federation commissioner Nancy Hedford (Elinor Donohue) back to the Enterprise to treat her illness, Sakuro’s Disease. Their shuttle is diverted, however, by an energy cloud, a life form they come to know as “The Companion.”

The Companion brings them to a planetoid to keep a lonely Robinson Crusoe-like castaway, Zefram Cochrane — the inventor of warp drive — company. Captain Kirk attempts to convince the Companion to let them return to the Enterprise so that Hedford might live, but learns that the Companion is in love with Zefram.

This fact horrifies Cochrane at first, because the Companion is so different in nature. He considers the Companion’s love indecent, even though the entity has kept him alive and nourished him for over a century. It has acted with love at every turn, and he has benefited from that love.

When it becomes clear that Hedford will die, the Companion joins with her, giving up immortality to live a short span as a mortal human. It sacrifices everything to keep Cochrane company, and that is a testament to its understanding of the true meaning of love that even Cochrane, in his ignorance, cannot fail to notice.

And my selection for the most underrated Star Trek episode is…

1. “Return of the Archons”

“Return of the Archons” is frequently lost in the Star Trek catalog shuffle because it is one of a number of “Kirk-destroys-super-computer-and-violates-the-Prime Directive”-episodes. Other examples are “A Taste of Armageddon,” “The Apple,” and “For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky.”

But “Return of the Archons” is Star Trek’s most serious and consistent indictment of organized religion.

“Return of the Archons” involves the Enterprise’s visit to Beta III, and a humanoid culture not unlike Earth of the 20th century. The most significant difference is that the people of Beta III dwell in a theocratic state, referring to themselves as being part of “The Body” and worshiping the omnipotent God figure from their history: Landru.

When Kirk’s landing party is nearly “absorbed” by hooded lawgivers, and the Enterprise is almost yanked from orbit by the mysterious Landru, Kirk sets out to destroy this vision of “paradise.”

In the end, Captain Kirk discovers the truth about the God called Landru: he is an advanced computer imposing a machine’s vision of “peace” upon the Betans.

Many of the details of “Return of the Archons” relate the culture of Beta III to organized religions right here on Earth. A man named Reger (Harry Townes), a denizen of Beta III, notes that Landru first came to the world 6,000 years ago and imposed his will. Tellingly, 6,000 years is the span that equates, to Young Earth Creationism’s belief about the time-frame for Earth’s genesis.

At other junctures in the story, “Return of the Archons” addresses ideas familiar from Christianity. When a citizen of Beta III leaves the flock, he or she is “absorbed” back into “The Body” by the Lawgivers, and consequently spiritually reborn as a devoted adherent. This process of “absorption” conforms to the idea in Christianity that “except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

Significantly, those who are “born again” into the world of Landru (like McCoy and Sulu) begin to aggressively “profess” the perfection of Landru, just as the born-again here on Earth often feel duty-bound “professing Jesus.”

This brand of religious “professing” dominates “The Return of the Archons” in frequently repeated phrases such as “It is the will of Landru.” Or “Do you say that Landru is not everywhere?”

The notion of “the will of Landru” is historically in keeping with such religious phraseology as “God willing,” “deux vult” or “Masha Allah,” the specific acknowledgment on the part of the faithful that life proceeds as according to an impenetrable divine plan.

The most cutting critique is also one that is shrouded in a double meaning. When Captain Kirk confronts this God, Landru, he dismisses the hologram as “a projection, unreal.” This remark is both a comment on Landru’s physical presence in the room and — albeit in code — his status as God. Some people might even state that the various versions of God created by man’s religions are also “projections,” but of the universal human desire to believe in a Divine Entity. “Return of the Archons” has often been considered a coded attack on Communism, but the episode speaks in the language of religion, not political ideology.

In addition to its impressive social commentary, “Return of the Archons” also features the “Red Hour”– twelve hour span of lawlessness on Beta — that has been termed part of the influential creative gestalt of the contemporary The Purge film series.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.