“It seemed somehow more shocking because this was a Saturday afternoon in the Wiltshire countryside. You understood this might happen behind the Iron Curtain, but in England? In Wiltshire? On a Saturday afternoon in the summer? In a Wiltshire field?”

– David Michael James Brudenell-Bruce, Earl of Cardigan

At around 7pm on 1 June 1985 over 1,300 police launched what proved to be their final attack of a busy day out in the sun-kissed English countryside. For much of the day they’d been attacking ‘The Convoy’ of Travellers in a bid to stop them reaching the 11th Stonehenge Free Festival.

The police plan had pretty much worked. But they wanted more. They attacked the Convoy, smashing windows, pulling people from their vehicles and making arrests. Panicked by the police violence meted out to people at the front of the Convoy, some Travellers turned off the road into a field beside the A303.

Police then waded into the field wielding truncheons and throwing missiles. In an effort to escape, Travellers drove from the grass field into the adjacent bean field.

The Convoy moves through Marlborough en route to Stonehenge in 1985

Police surrounded them. They prevented people from getting in or out. According to journalist Nick Davies, the police changed into riot gear, drew their truncheons and charged. The 600 or so New Age Travellers who’d been trapped in the bean field were subjected to a prolonged and bloody attack by police.

“They were like flies around rotten meat,” said Davis of the police, “and there was no question of trying to make a lawful arrest. They crawled all over, truncheons flailing, hitting anybody they could reach. It was extremely violent and very sickening.”

The police clubbed pregnant women and those holding babies with truncheons, “threw anything they could lay their hands on – fire extinguishers, stones, shields and truncheons – at them” and systematically smashed to pieces the Travellers’ vehicles, setting several on fire. For added spite, the police seized healthy dogs belonging to the Travellers, which were put down by officers from the RSPCA.

In total, 537 people were arrested – the most arrests to take place on any single day since the Second World War. They were each charged with obstruction of the police and the highway, but most of the charges were dismissed in the courts.

The Build Up To Ultra-Violence

A family trip to Stonehenge in 1875

Some of the Travellers knew a High Court injunction had been taken out prohibiting the gathering on Salisbury Plain by Stonehenge, an ancient meeting place. The ban was the result of ‘local opposition’ to damage to Stonehenge, and land owners’ complaints about trespassing, damage to property, drug taking and people washing naked in the rivers.

Only about 500 people had arrived at the first Stonehenge Free Festival in 1974. But it’d grown, and by the early 1980s, the number of revellers had reached 30,000.

People were looking for alternatives to living in living in pokey homes and struggling to find work to pay for them. More and more people were joining an alternative way of life. At Stonehenge they would connect with the ancestors and find meaning and purpose in a different sort of society.

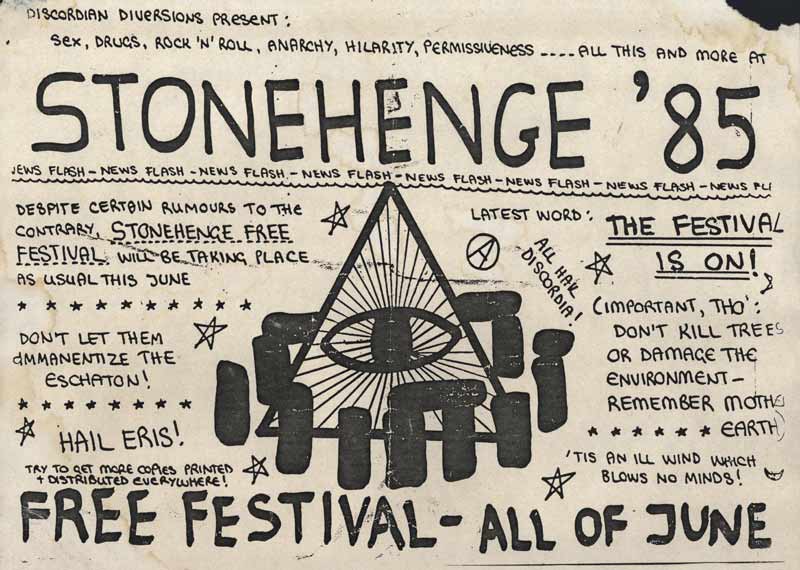

Flyer for the 1984 Stonehenge free festival. From our story The Last Stonehenge Free Festival in Photos (1984)

From our story: ‘Sex n Drugs n Rock n Roll’ – The Last Stonehenge Free Festival in Photos (1984)

But would so many people place the Stones in jeopardy? Where do that many people go to the toilet? Rather than leave it for the people running the festival and those employed in its economy to work things out for themselves, the State decided that it should be banned. The end would be abrupt and bloody.

A fence of barbed wire encircled the Henge. The monument was patrolled by security guards with dogs, employed by English Heritage, the historic buildings organisation which had first sought the injunction to prevent the annual free festival being held.

An exclusion zone was installed four miles around the festival site. To stop the Travellers, police tipped lorry-loads of gravel over the main route in and blocked the detour with cars, vans and motorbikes.

Waiting for the Convoy

The story goes that police intelligence had suggested the Travellers were armed with petrol bombs and firearms. They weren’t. What they had were children, vehicles they’d made into homes – with maybe a few out-of-date or missing tax discs – and a way of life centred on communal living and free festivals that was about to be crushed.

Faced with the blockade seven miles from the festival site, the Convoy of around 140 vehicles was brought to a halt.

The First Attack

Eyewitnesses say a platoon of police, many not with no identification numbers visible, ran towards the Convoy. They carried shields, batons and some had portable fire extinguishers for fear of petrol bombs. They smashed windscreens and began to make arrests. Reports say that some of the group did throw stones and sticks at the police. But what would become the Battle of the Beanfield was a one-sided assault.

Helen Hatt was 19. Working as a children’s entertainer, she was in the Convoy because it felt safer to travel in numbers than alone. Her vehicle was insured and taxed:

“I saw police coming down the line smashing up the windows. I was screaming at the top of my lungs, ‘Just tell me what to do and I’ll do it’. They were screaming at me ‘Stop the vehicle, stop the vehicle’…

One of them climbed on the bonnet and began hammering on the windscreen. Another smashed her side window.

“They tried to pull me out of the window but it was too small for me to actually get out of it. They kept tugging at my hair, trying to pull me out.

“There was a tug of war between the police officers. They ripped chunks of my hair out and the copper on the inside struck me with his truncheon on my leg so hard, that to this day I have a huge dent in the muscle of my leg.”

Seeing what was happening at the head of the Convoy, people behind began to panic. They broke fences and drove into a field. And for a few hours not much happened. The Travellers tried to negotiate with police. They asked for help. But police don’t listen. They tell.

Nick Davies: “Eventually Lionel Grundy, who was then the Assistant Chief Constable, arrived on the scene and made it quite clear that there were to be no negotiations and that everybody in the field was to be, what he called, ‘arrested and processed’.”

Assistant Chief Constable Lionel Grundy, Operational Commander: “Those of you who come out under those circumstances will be interviewed and dealt with. If I suspect that you’ve been involved with any of the offences that have occurred today, then you will be arrested. I’m not here to bargain with you. I’m here to say something to you for you to consider.”

More police arrived. Reports allege soldiers dressed as ‘special constables’ joined the ranks. And at 7pm, they attacked.

The Law of the Land

In a BBC article from 2014, we’re told “the events ahead of solstice day in 1985 are still hotly disputed”. There are conflicting accounts. The BBC had not been in the bean field to report on the frenzied attack, preferring to remain behind police lines.

“Whilst the Stonehenge Free Festival was illegal, it is not easy to prevent several hundred people, leave alone several thousand, from doing something which in their eyes they feel they should be allowed to do,” retired officer Peter Spencer tells the BBC. “Consequently, the festivals of the 70s and early 80s could only be policed on the fringes… It had gone completely out of hand… you just don’t want that sort of thing.”

Rose Brash was in the bean field. She recalled:

“On that incredibly hot day in 1985, we encountered road blocks on the way to Stonehenge and ended up marooned on farmland seven miles from the site. We parked in a broad bean field and, over a few hours, watched as the police numbers swelled to about 1,300. We could sense the mood changing, so I stuck a sign in the windscreen: “Six-month-old baby on board. We don’t want any trouble.”

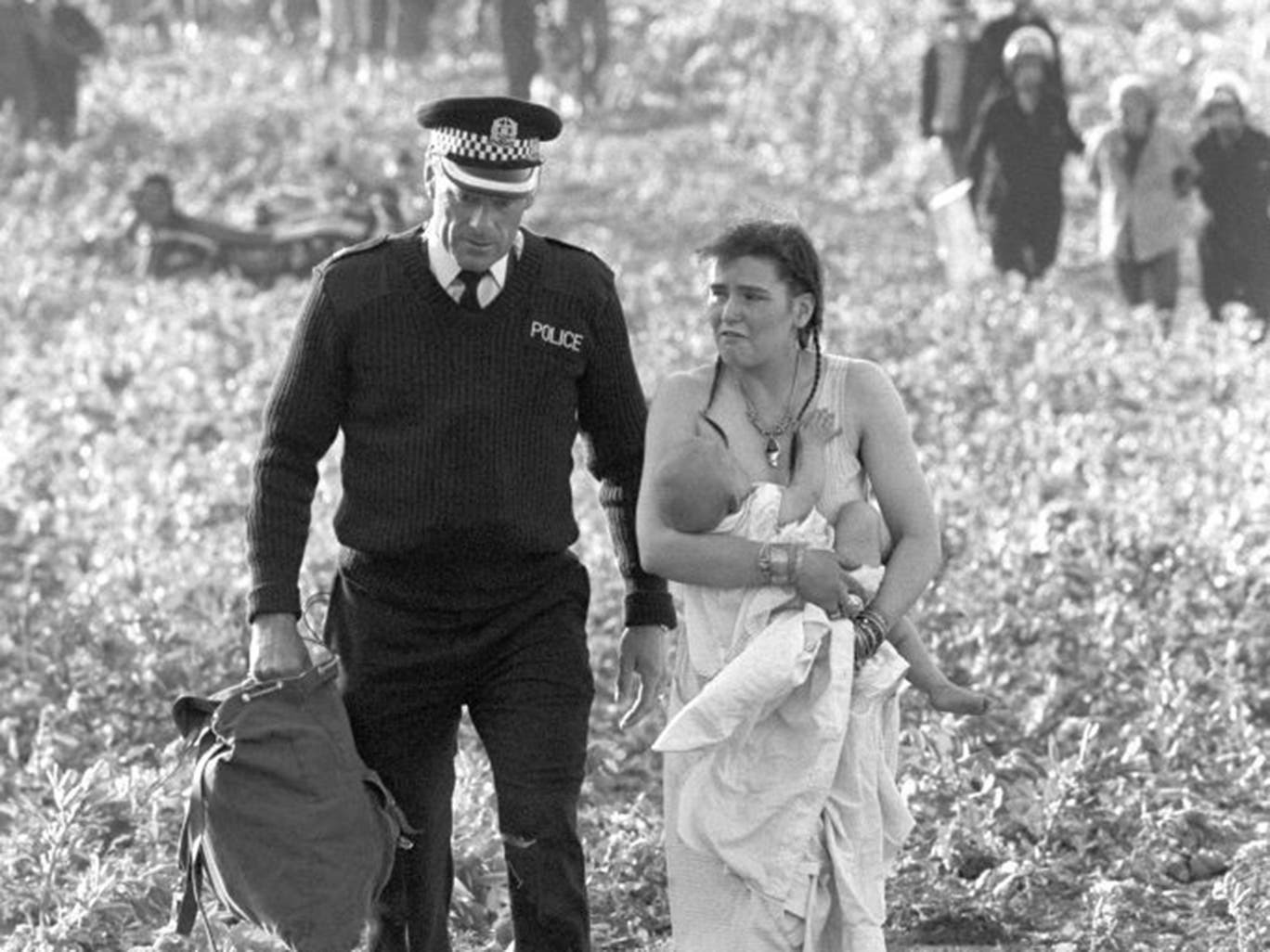

“Soon after, I was pulled out of the bus, even though I had my daughter Kaya in my arms. The copper with me in the photograph [that’s Rose on cover of the book above] looks as if he’s helping, leading me to safety, but he was only doing it for the sake of the cameras. Once we got to the field, he pushed me away to join others who were being arrested for obstructing the police and the highway.”

William Turner of Oxford (1789–1862), Stonehenge-Twilight c.1840, Watercolour. The print.

Witnesses: TV and the Toff

Kim Sabido was in the bean field. Working for ITN, he delivered this commentary, which was removed when the evening news bulletin was broadcast:

“What we’ve witnessed in the last half hour here has been surely some of the most brutal action by the police forces in Britain for a long time, whatever the causes the end product seemed to be just hitting out wildly by the police .Young women with babies in their arms were hit as well.

“At one stage one of the cameramen from Fleet Street was arrested for being on this site – we were pushed and shoved to one side, but the worst of it all was that the people in those coaches who were trying to escape from the police were just grabbed , their windows were smashed and they themselves were just beaten , sometimes senselessly ,on the floor.”

He would add:

“When I got back to ITN during the following week and I went to the library to look at all the rushes, most of what I’d thought we’d shot was no longer there. From what I’ve seen of what ITN has provided since, it just disappeared, particularly some of the nastier shots.”

James Cameron was a Wiltshire Radio reporter in 1985:

“The police called in support from police forces around the country, and they arrived and kitted themselves up in riot gear, and effectively surrounded the convoy.

“There was a small group of… I suppose one would call them anarchists. They started pelting the police lines with stones and stuff they picked up from the field and there was this strange stand-off between the police, who were reluctant to go in, and this group of anarchists who were goading them.

“I was standing by a police van and one ball-bearing hit the police van right beside my head.

“Then at some stage the police took the decision to go in.

“There was this extraordinary scene where you had a helicopter overhead with police shouting instructions through a loud speaker and you had a large number of police rush on to the field from all sides who started smashing the windows of the buses.

“It was like something out of the Wild West. There were these huge buses and cars and vans all charging around in circles. The buses were trying to run the police down, the police were trying to stop them.

“They [the police] would smash the sides of the bus windows with the batons and drag anyone they could find inside out.

“There was a lot of screaming, a lot of shouting and with the noise of the helicopter overhead, the whole thing felt extremely intimidating and terrifying.”

The Earl of Cardigan, whose family owned Savernake Forest between Marlborough and Great Bedwyn, where the convoy had stayed the night before, also bore witness. He was secretary of the Marlborough Conservative Association and manager of Savernake Forest (on behalf of his father the Marquis of Ailesbury).

He’d travelled along with the Convoy on a motorbike accompanied by fellow Conservative Association member John Moore. They thought “it would be interesting to follow the events personally”. Wearing crash helmets to disguise their identity, they witnessed the mayhem.

“There was an element of anarchists amongst them,” the Earl said, “the more voluble and vocal ones that were sounding off – but they were a small minority. The rest seemed utterly unremarkable family groups for whom living in a motor coach was their chosen way of life. There were kids everywhere.”

What else?

“From behind the barricade came around two dozen policemen with their truncheons drawn. They smashed through the first vehicle’s windscreen, hauled out the occupant and then hauled him off to custody.

“The second vehicle was a converted ambulance with a lone girl in it. I was standing on the roadside bank right beside that vehicle, so I could see them smash up her windscreen. I saw four or five policemen climb in and they dragged her out through a broken window by her hair, right over the broken glass.”

…

“…the smashing up of the vehicles and the instructions to ‘Get Out! Get Out! Get Out!’ and hand over your keys were given simultaneously and therefore there was no chance to understand what was being shouted at you, and to comply before your vehicle started disintegrating around you with your windscreen broken in and your side panels beaten by truncheons and so on.”

…

“The police would throw missiles at the windscreens, thereby covering the drivers with broken glass…”

“There were some very large flints in the field, about the size of cantaloupe melons, and the police were throwing those. They flung their shields like frisbees, and they carried small metal fire extinguishers which they also threw. By now the police had a real rush of blood up.

..

“At some point in the crazy melee there was a heavily pregnant woman wandering around. Two policemen came up behind her with batons and clubbed her around the head and shoulders, and down she went.”

…

“All of this was simply terrible to witness at such very close range. But when I sought to write down the identification numbers of some of the worst offenders I saw to my horror and anger that many of the officers in question had their ID covered up.”

Largely as a result of his testimony, police charges against members of the convoy were rejected in the Crown Court. In relation to this several national newspapers criticised the Earl and questioned his suitability as a witness. He successfully sued these papers for claiming that he made false statements and that he was providing accommodation for the New Age Travellers. Cardigan later said:

“I hadn’t realised that anybody that appeared to be supporting elements that stood against the establishment would be savaged by establishment newspapers. Now one thinks about it, nothing could be more natural. I hadn’t realised that I would be considered a class traitor. If I see a policeman repeatedly truncheoning a very pregnant woman over the head from behind (as I did) I do feel I’m entitled to say “that’s a terrible thing you’re doing, Officer”. I went along, saw a dreadful episode in British Police history, and simply reported what I saw.”

There was no inquest. Nothing marks the scene of so much police violence. If justice does arrive, it could come when all those involved are in their dotage or dead.

What the Government did do was to introduce the 1986 Public Order Act. They defined a riot as when a group of 12 or more people present together use threatening violence or have the intent to use unlawful violence for a common purpose, that will cause some with reasonable resolve to fear for their safety. Affray was when two or more people use or intend to use threatening behaviour which would cause those present to fear for their safety.

Six days’ written notice must be given to the police before most public processions. Police could impose unspecified “conditions” if they feared that a procession “may result in serious public disorder, serious damage to property or serious disruption to the life of the community.”

And now? Well, the big festival is in Glastonbury, about 40 miles to the west of Stonehenge. The BBC presenters fronting the State broadcaster’s televising of the festival call it ‘Glasto’. It has a huge perimeter fence to keep non-paying ticket holders out, security guards, a VIP area and in 2023 the RAF display team, the Red Arrows, flew overhead. It’s a haven for Centrist Dad and people who say ‘It’s Wine ‘o’Clock’.

Counter-culture goes on, of course. But it can be hard to find.

You can see Andy Worthington’s photographs of the Battle of the Beanfield on his site.

And Alan Lodge, who was also there, has more.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.