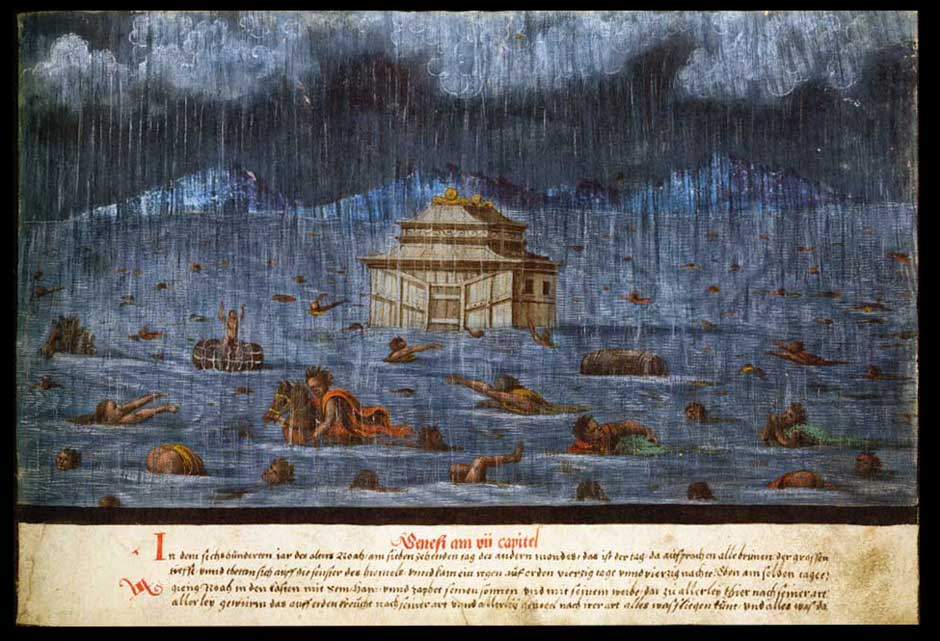

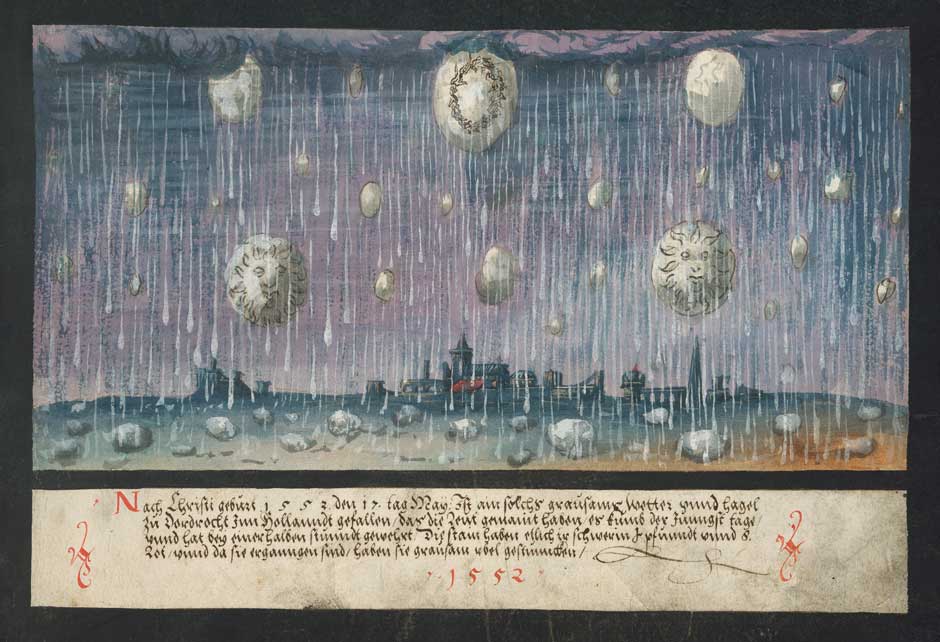

We can’t be certain who wrote the Augsburg Book of Miraculous Signs, a luxuriously illustrated Roman manuscript that in 1552 thrilled residents of the Swabian Imperial Free City of Augsburg. This anonymous encomium to God deals with omens, nightmares and portents, each unsettling picture of phantasmagoria from Genesis to the then present day painted in gouache and watercolor.

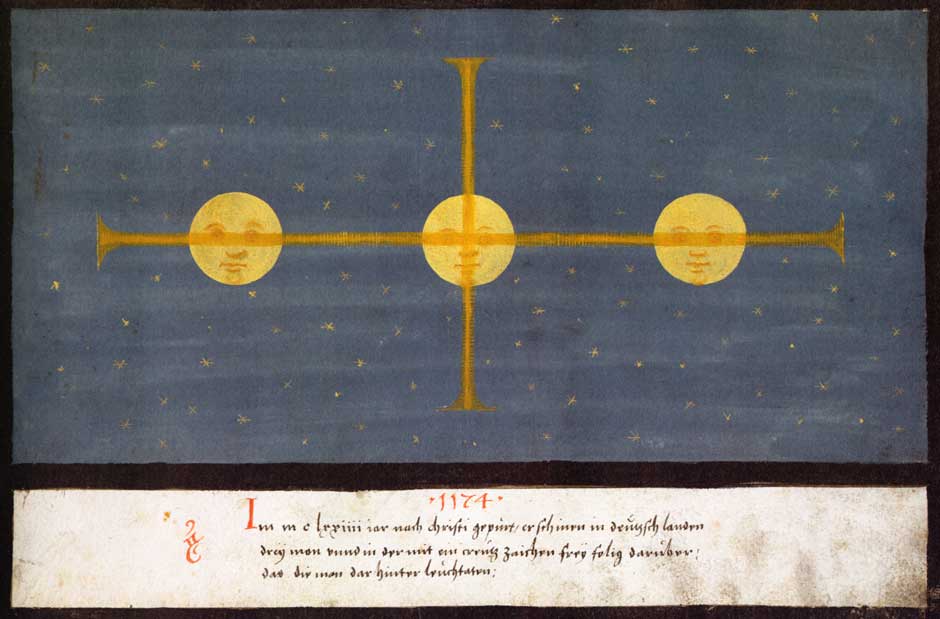

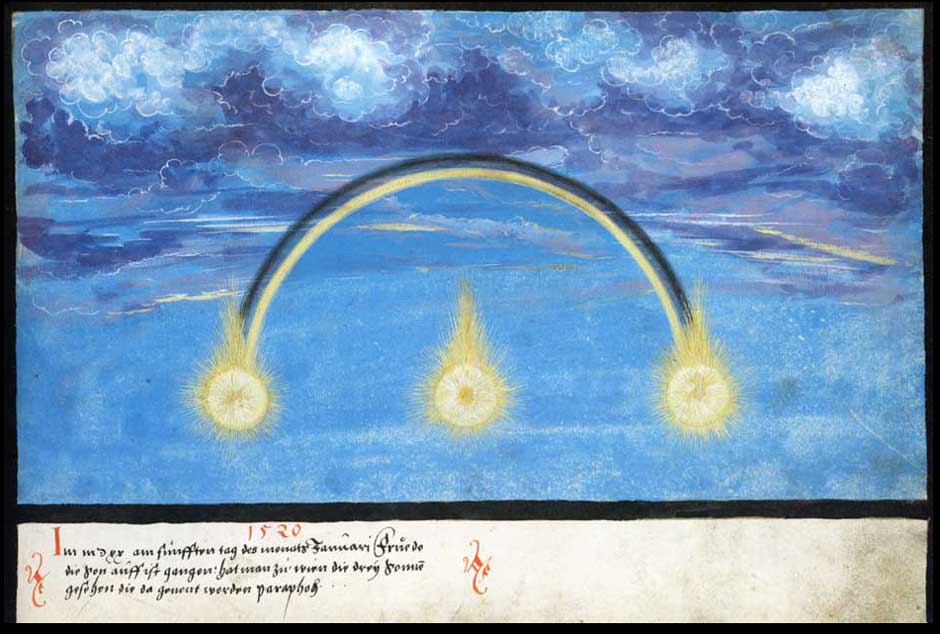

Medieval readers in what is now modern day Germany yearned for dramatic symbols from above, obsessed with searching the cosmos for signs of God’s love and designs for His creation. The more violent, discordant and terrifying these messages the better. The default facial expression of the 16th Century Germans was a permanent Heaven-wards grimace to the divine God-bomber.

Joshua P. Waterman, of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, pulled together 169 of these images for a updated version of the work re-named The Book of Miracles. He notes:

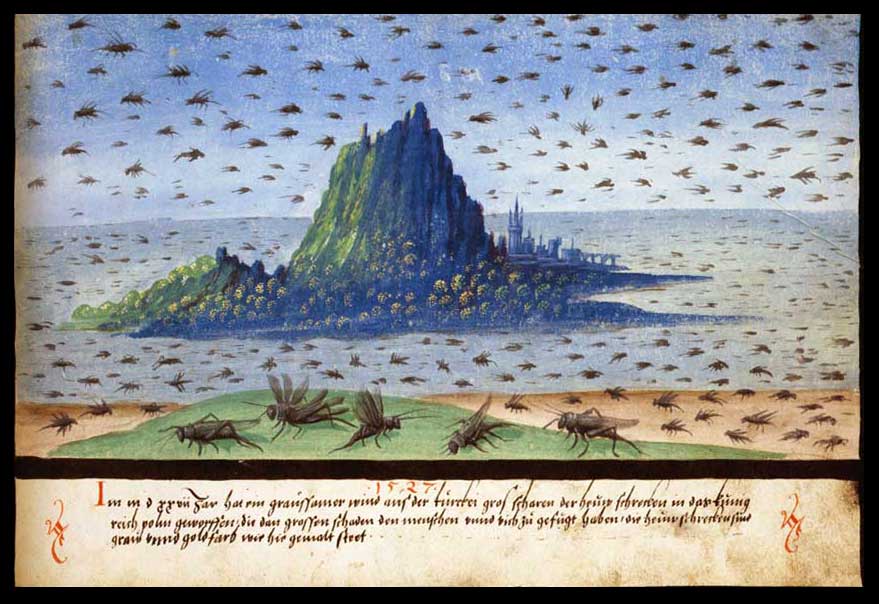

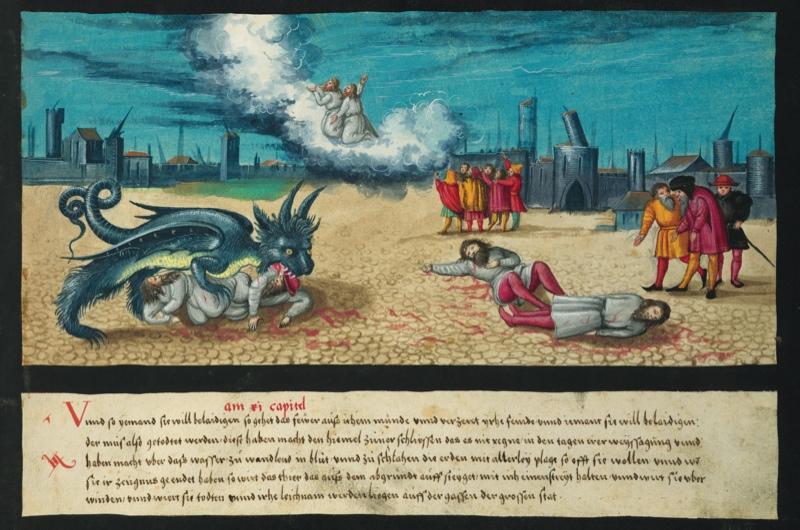

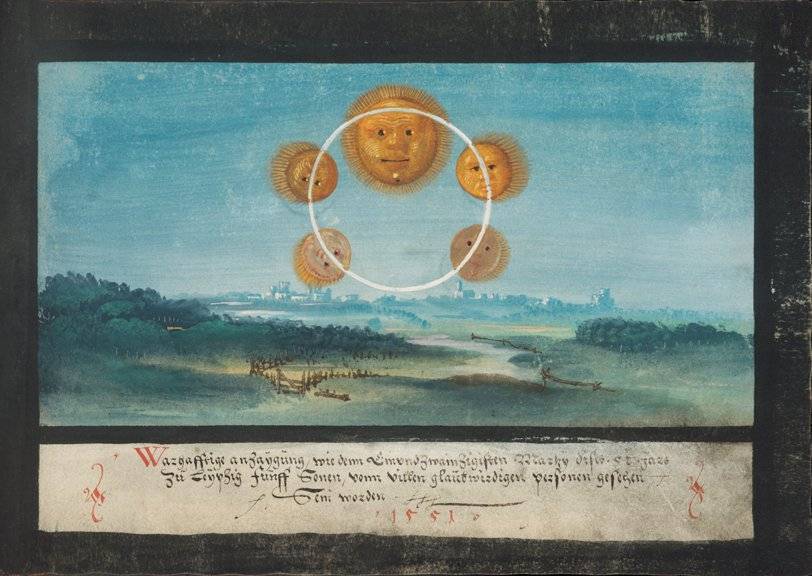

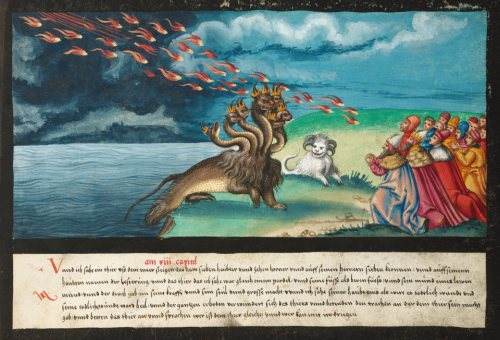

The unidentified patron who commissioned this manuscript wanted to create a stunning visual experience…. The Protestant viewer would have reflected on the greater significance of these wonders: Why are there dragons in the sky? Why does it rain blood? Why are there three suns overhead? We know from contemporary sources that the answer was general: Things are wrong in the world. Repent and prepare for the end times, which are possibly now.

They implied moral improvement could mark a path not only to a better existence on earth, but also eternal life. Unfortunately, the catastrophes in the book—earthquakes, floods, storms, fires, and volcanic eruptions—are still all too relevant.

Marina Warner adds footnotes to the images:

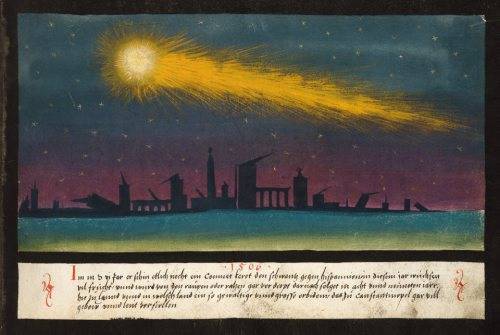

The word, comet, comes from the Latin for hair, comes, and the tails of meteors as they streamed through the sky were imagined to be golden hair like the goddesses’ in Homer. This gorgeous portent, richly pigmented in thick gamboge yellow and paler primrose gold, against a star-flecked grey-blue night, was reported to appear at the time of Muhammad’s birth over the city of Constantinople.

This marvellous hybrid was left stranded and dead after the flooding of the river Tiber in 1496 subsided. Like medieval images of the Devil, the creature’s form is ambiguously male and female, reptilian and mammalian; news of its appearance circulated in broadsheets, and became notorious after the reformers adapted the image to represent “the Papal Ass,” agent of the evils of the Church of Rome. But to modern eyes, trained by Surrealism, this monster has an appealing fancifulness, not so much threatening as comic.

In 1531, around two hundred years before the terrible earthquake in Lisbon, which galvanized Voltaire’s revolt against the idea of Divine Providence, the city was shaken and “more than a thousand people killed.” The inscription says that a whale was seen in the sky, along with streaks of blood, but in the picture the beast rages in his more natural element.

“In the year 1506, comet appeared for several nights and turned its tail towards Spain. In this year, a lot of fruit grew and was completely destroyed by caterpillars or rats. This was followed by an earthquake in the eighth and ninth year in this country and in Italy, so great and violent that in Constantinople a great many buildings were knocked down and people perished.”

Via: Taschen, Marina Warner NY Books

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.