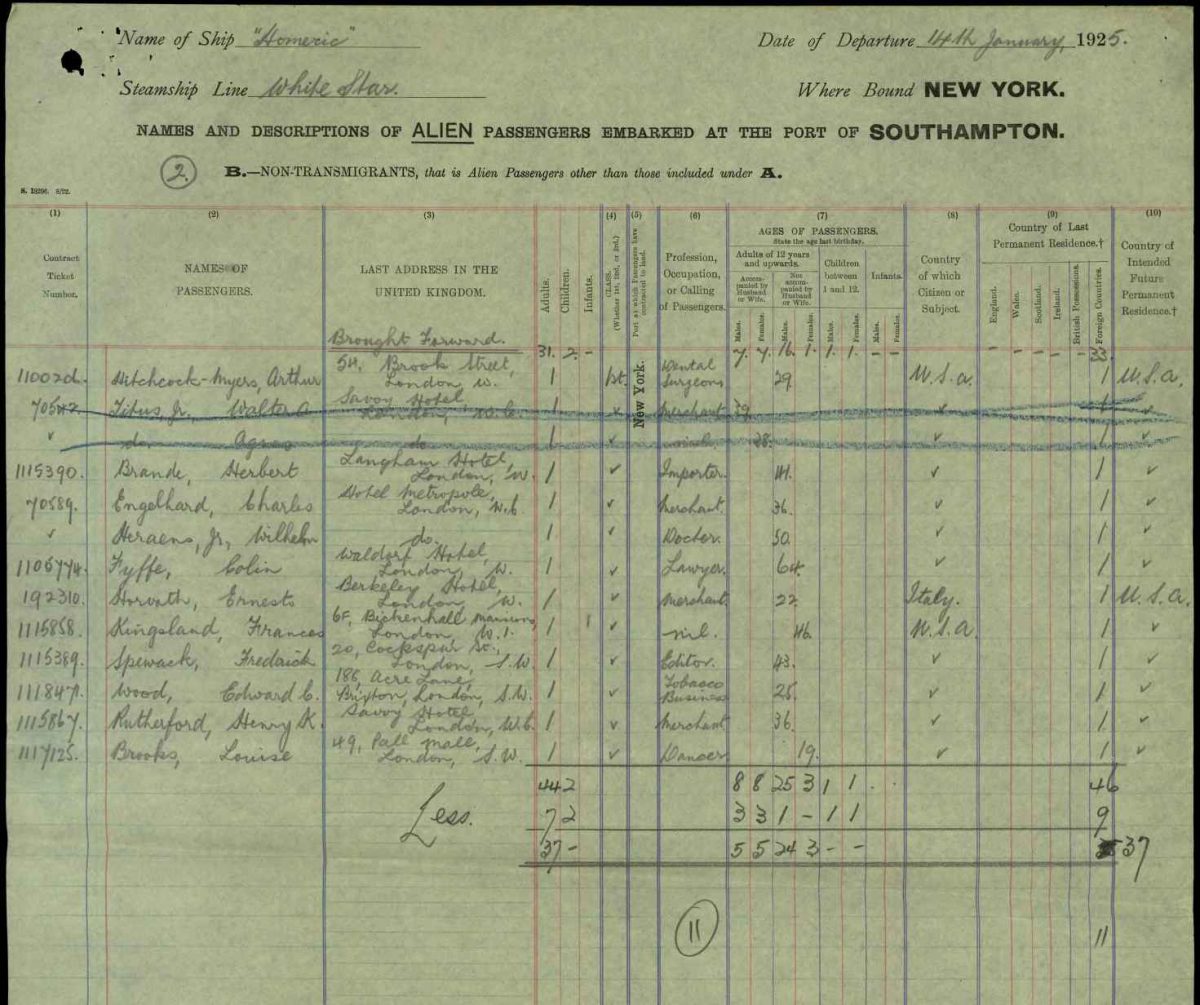

Visiting England, apparently on a whim and a year before she appeared in her first film The Street of Forgotten Men late in 1924, Louise Brooks became a dancer at the newly opened Café de Paris in Coventry Street. She was seventeen, and during a particularly cold and dismal winter, she reputedly became the first person to dance the Charleston in London. She was certainly the first to be noticed anyway. Brooks later wrote about her time in the capital: ‘I was living beyond my means – who doesn’t at seventeen? – in a flat at 49A Pall Mall.’ Although her dancing was a stunning success with the Piccadilly nightclub crowd – nobody had seen anything quite like it before – she was lonely. Despite trying and enjoying Christmas pudding for the first time then living off it for a week and making good friends with the housemaid Brooks didn’t last long in London. On 14 January 1925 she travelled on the White Star liner RMS Homeric back to New York. She left London almost as suddenly as she had arrived.

Louise Brooks travelled back to the US on the RMS Homeric – she’s lied about her age. She was just 18 when she returned home.

The Café de Paris had opened towards the end of 1924 after George Foster, an eminent theatrical agent who had once represented Harry Lauder, Charlie Chaplin and George Formby Senior, had been looking for a venue where he could introduce new cabaret artistes and dance bands. He came across a restaurant called the Elysée on Coventry Street, a few yards from Piccadilly Circus and, with Captain Robin Humphreys, bought the lease and had the good sense to take on Martin Poulsen, the Danish maître d‘ from the Embassy Club. The venue featured a glamorous staircase that led down to the basement-level dance floor and restaurant, which was said to be a replica of the Palm Court on board the ill-fated RMS Lusitania.

Business was initially quite slow until Poulsen contacted the Prince of Wales, who had once promised him that if he ever had his own restaurant he would attend. One Wednesday evening the prince made good his promise and dropped by. He was accompanied by his usual motley entourage that included Mrs Dudley Ward, his relatively long-term mistress whom he was occasionally wont to call ‘Fredie-wedie’, his equerry Major ‘Fruity’ Metcalfe and finally his aide, the one-armed Brigadier-General Gerald Trotter known usually to his friends as ‘G’. The Prince of Wales was entranced by the oval, mirrored room and the relatively spacious dance floor and soon became a regular visitor. This invaluable early royal patronage made the Café de Paris the fashionable place to be and it soon became the habitual home of much of the ‘Fast Set’, the ‘Smart Set’ or the ‘Bright Young Things’. Louise Brooks later wrote about this young group of aristocrats and socialites she had come across during her brief time in London, and described them as a ‘dreadful, moribund lot’. Referring to Evelyn Waugh and his novel Vile Bodies, she said only a genius could have possibly created a masterpiece out of such glum material.

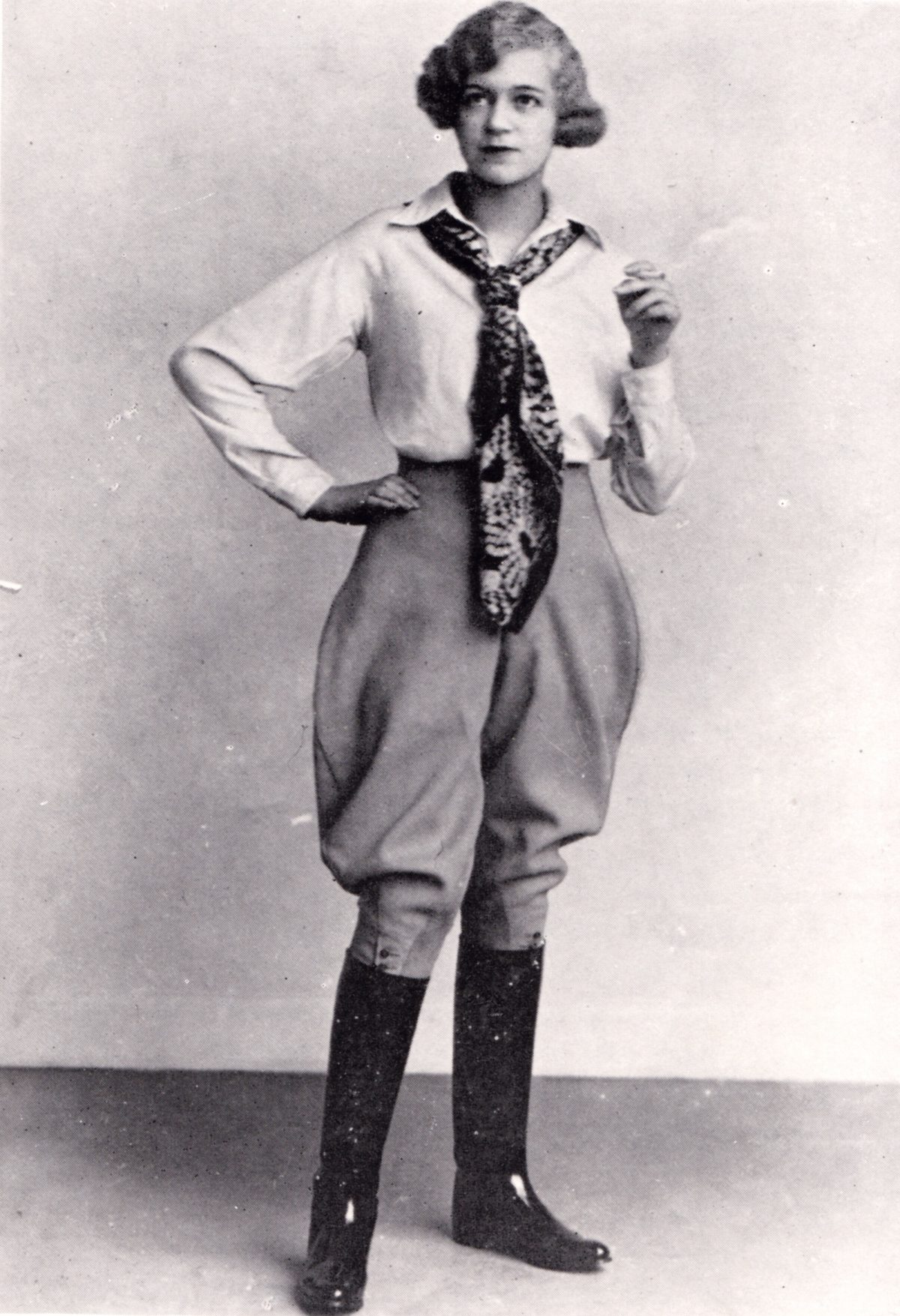

Marion Harris

In May 1932, and nearly eight years after Brooks danced in front of an adoring Café de Paris crowd, the thirty-six-year-old celebrated American singer Marion Harris was in the middle of one of her long engagements at the same West End nightclub. She had recently been appearing in the musicalEvergreen and was known to British audiences of the time as the first white woman to sing the blues. Today’s ears would perhaps agree with the more accurate description in a contemporary Manchester Guardian review when they described her as a ‘Diseuse with a very pleasant style and songs’. Enjoying her success with the British public, she moved to London at the beginning of the thirties and performed regularly for the BBC. Her most famous song in this country, a hit in 1931 and recorded with Billy Mason and his Café de Paris Band, was ‘My Canary’s Got Circles Under Its Eyes’:

I thought he’d never do anything wrong

Now he does snake-hips the whole day long

My canary has circles under his eyes

The Prince of Wales was a fan of Marion Harris and would often come to the Café de Paris just to hear her sing. One night after she had performed, the manager came running into her dressing room to announce that the prince had been so impressed that he would like her to have a drink at his table. Miss Harris coolly declined, telling him, ‘If your customers get to know you too well, they don’t come back and pay money to see you. The illusion is destroyed.’

Harris may well have been on the Café de Paris stage – the cabaret acts began their set at 11:30 – when just after midnight on30 May 1932 an intoxicated couple arrived for a rather late supper. The lateness of the hour was not unusual. Margaret Whigham, the ‘debutante of 1930’ and later the Duchess of Argyll, remembered that in the early 1930s she would go with one young man for dinner, feign tiredness and be taken home at 10.30, only to go out again with another man to dance at the Embassy Club or the Café de Paris. Elvira Barney and her lover Michael Stephen travelled by cab to Coventry Street after holding one of their numerous parties at the home they shared at 21 Williams Mews, just off Lowndes Square in Knightsbridge. After finishing their meal at the Café de Paris, they had further drinks at The Blue Angel in Dean Street before returning home in the early hours of that morning.

Margaret Whigham, at the ‘Jewels of Empire’ Ball at Brook House, Park Lane, 1930

Elvira Barney

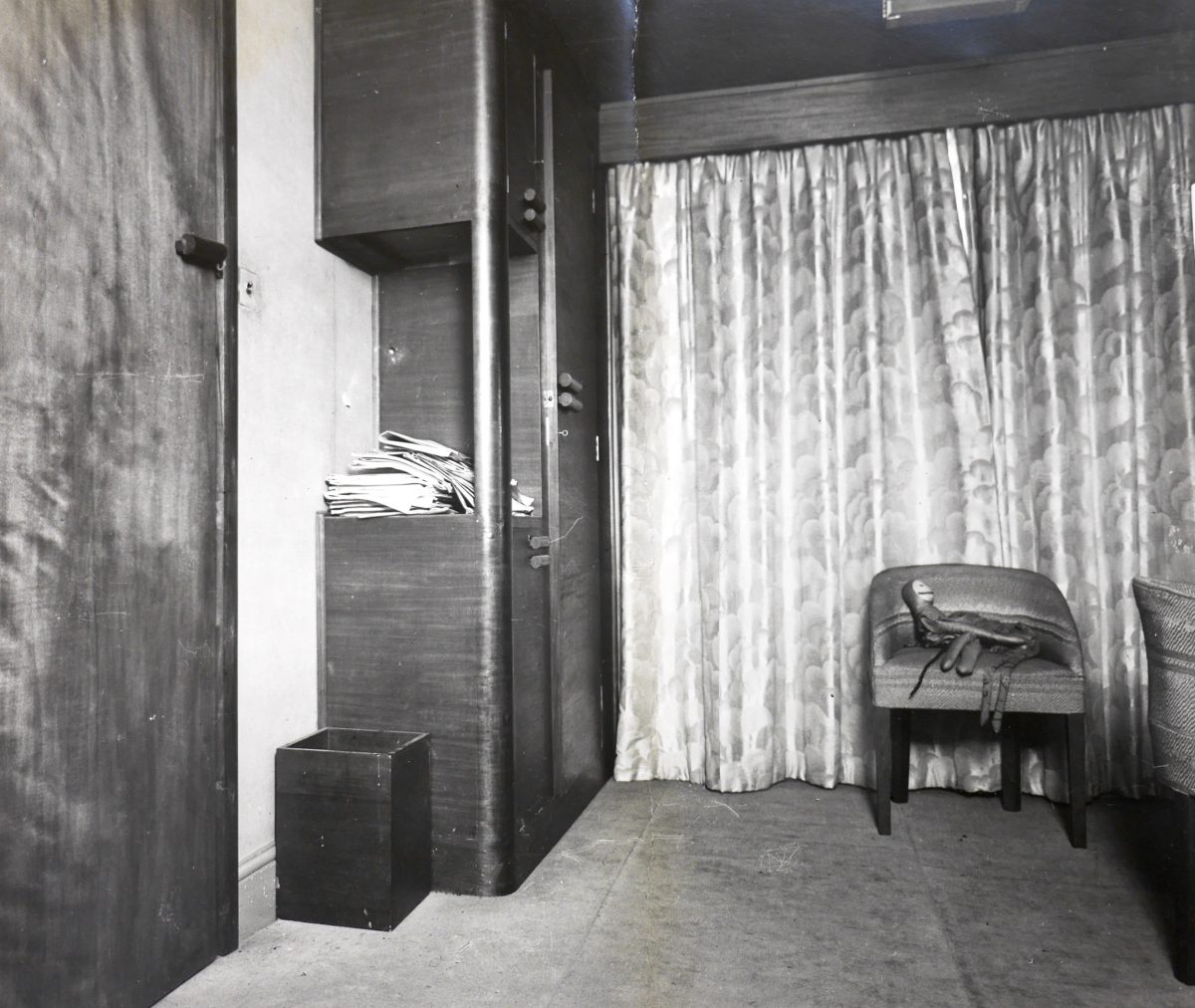

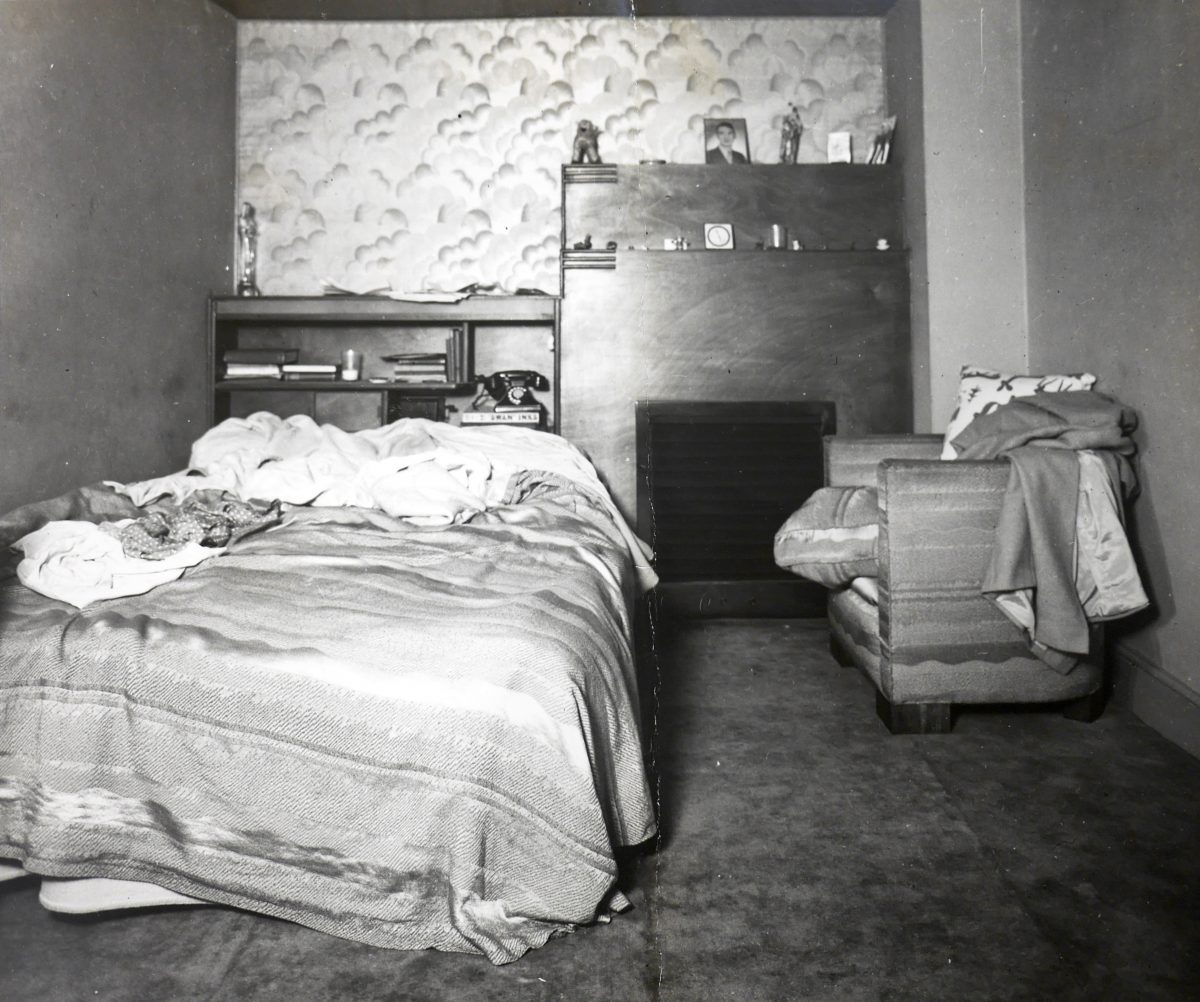

William Mews in knightsbridge, 1932

Not long after they had returned, neighbours heard screaming and shouting from the first floor of the couple’s mews house. One neighbour said she heard, ‘Get out, get out! I will shoot you! I will shoot you!’ Not long after, the entire street heard a pistol shot echoing into the night and then the sound of a woman plaintively crying. In between the sobs, another neighbour heard, ‘Chicken, chicken, come back to me. I will do anything you want me to.’ Drunken dramatics were not unusual at number 21 and not one person bothered to get up and check what was going on. They had heard it all before. ‘There was a terrible barney at no. 21,’ a neighbour later told the police, with an unintended pun.

At about 4.50 a.m. a doctor was woken by a telephone call and he managed to hear through hysterical crying someone say, ‘It is Mrs Barney. Oh, doctor, come at once. There has been a terrible accident. For God’s sake, come at once.’ When Doctor Thomas Durrant arrived at Williams Mews he came across Barney ‘in a condition of extreme hysteria and continually repeating, “He wanted to see you to tell you it was only an accident. He wanted to see you to tell you it was only an accident.”’ On the stairs, shot in the chest at close range, lay a distinctly dead Michael Stephen. Despite Elvira’s protestations, the doctor insisted that they had to call the police. The writer Macdonald Hastings (Max’s father) wrote about the fateful evening in his book about the firearms and ballistics expert Robert Churchill and described how shocked the police were when they encountered the scene at the mews house for the first time: ‘Over the cocktail bar in the corner of the sitting room there was a wall painting which would have been a sensation in a brothel in Pompeii. The library was furnished with publications which could never have passed through His Majesty’s Customs. The place was equipped with the implements of fetishism and perversion.’

William Mews interior, 1932

William Mews interior 1932

Shocked they may well have been, and despite Elvira at one point striking Inspector Campion in the face and saying, ‘I will teach you to say you will put me in a cell, you vile swine,’ the Metropolitan Police in 1932 knew their place and the murder suspect was only subjected to gentle questioning. She soon told them, however, that there had been an argument during which her boyfriend, Michael Stephens, had said he was leaving her, to which she had replied by threatening to kill herself with a revolver that she kept by the side of her bed. During their ensuing struggle when he tried to get the gun from her grasp the weapon suddenlyfired into Stephen’s body. She was unsure whose finger was actually on the trigger. It would be exactly the same story that she told all the way through her subsequent ordeal. After Elvira’s parents, Sir John and Lady Mullens, arrived at the station, the police kindly allowed the main suspect of a likely murder case to go back home nearby at 6 Belgrave Square. The 1911 census, incidentally, shows that the Mullens shared their house with twenty-three live-in servants, and still twenty-one years later several liveried footmen greeted the Mullens when they arrived home.

Three days after she had shot Michael Stephens, accidentally or otherwise, Elvira was arrested and charged with his murder. The police had no choice when, after questioning neighbours about the shooting, they found out there had been a witnesses to a previous altercation between Mrs Barney and Stephen. After one loud quarrel Stephen had stormed out of the house and started walking away, at which point a window on the first floor opened and a naked Mrs Barney was heard shouting, ‘Laugh, baby. Laugh for the last time!’ At which point she produced her revolver and shot at Stephen from the window.

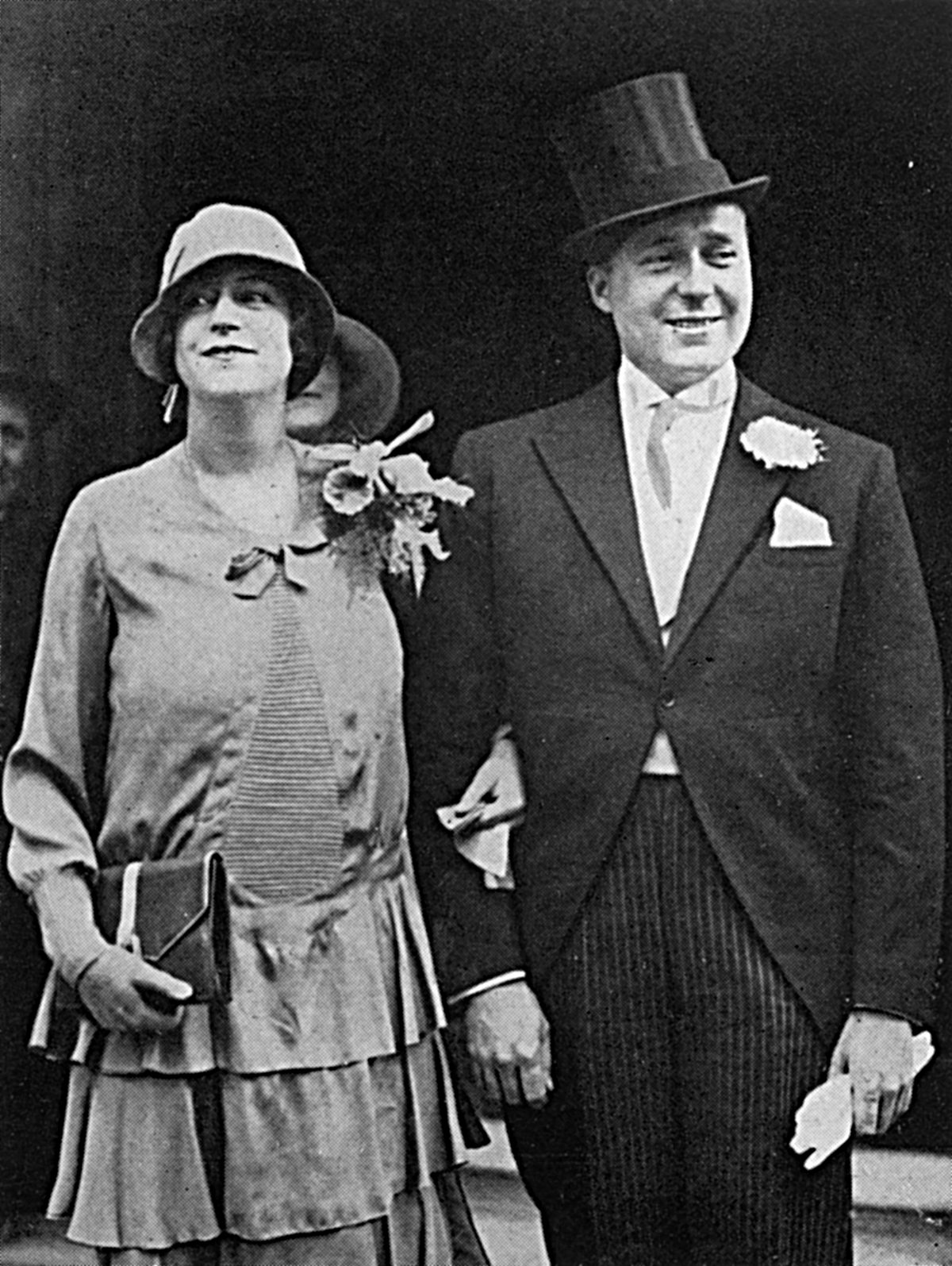

After their wedding ceremony/ Miss Elvira D. Mullens and Mr J. S. Barney, the New York Vocalist.

Four years previously, a twenty-three-year-old Elvira, despite her parents’ protestations, had married an American singer and entertainer called John Sterling Barney. They had met at a society function held by Lady Mullens where he had been performing in a ‘top-hat, white-tie and tails’ trio called The Three New-Yorkers. The three entertainers were relatively successful at the time and, indeed, often performed in cabaret at the Café de Paris. By many accounts, however, John Barney was a rather unpleasant man, and a friend of Elvira’s called Effie Leigh once recalled, ‘One day she held her arms in the air and the burns she displayed – there and elsewhere – were, she insisted, the work of her husband who had delighted in crushing his lighted cigarettes out from time to time on her bare skin.’ Violent rows had started within weeks of the marriage ceremony and after a few months the American went back to the United States, never really to be heard of again. Elvira, according to her biographer Peter Cotes, went off the rails and ‘started sniffing the snow … and became the demanding but generous mistress of a number of disorientated and sexually odd lovers’. The description goes someway to explain how, at the start of 1932, she ended up sharing her bed (and her not insubstantial bank account) with the drug-dealing ex-‘dress-designer’ Michael Scott Stephen, a man who was more than happy to accompany her as she ‘drifted into flagrant immorality’.

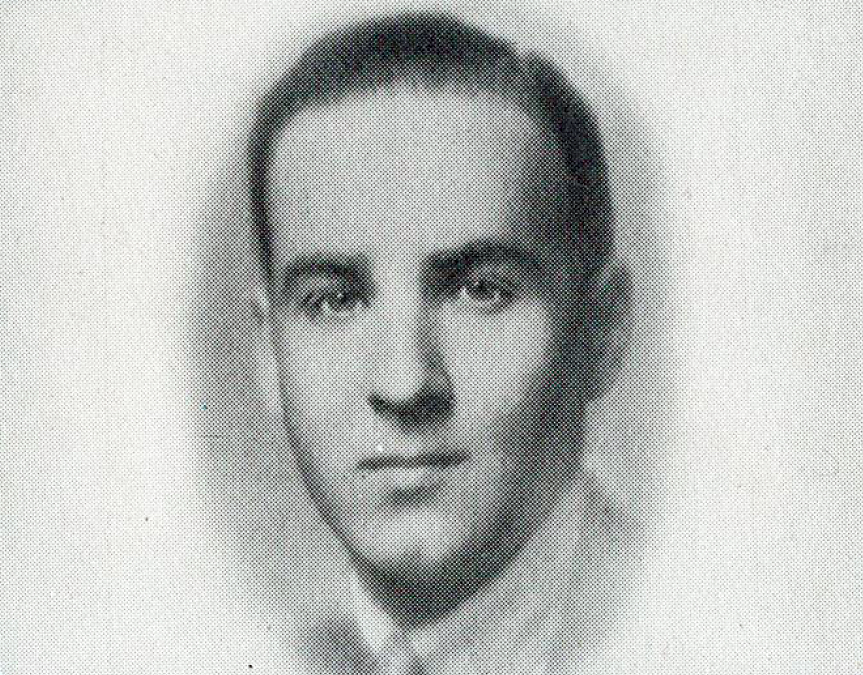

Michael Stephen

The Daily Mirror the day after the murder

On Saturday 4 June, after spending the night in a cell at the Gerald Road police station in Victoria, a pale Elvira Barney, dressed in a long black coat with her fair hair covered by a black cloche hat trimmed with white, was driven to the Westminster police court on Rochester Road. She was charged with murder and accused of shooting Thomas William Scott Stephen, after which she was remanded for a week. After hearing the charge, Elvira staggered a few steps and collapsed into the arms of a female warder guarding her. Police officers carried her from the court and after doctors had attended her for an hour she was taken to Holloway Prison.

Sir John Mullens, with his society connections and wealth, managed to persuade the former attorney-general, Sir Patrick Hastings, to defend his daughter. In 1932 Hastings, in his early fifties, was at the height of his fame as king’s council. In his book Cases in Court, published in 1949, Sir Patrick describes his first sighting of Elvira:

She had been described in the Press as ‘a beautiful member of the so-called “smart set”’, but no doubt partly by reason of the ordeal which she had undergone, and partly in consequence of the life she had been leading, her appearance was not calculated to move the hearts of a jury; indeed she was a melancholy and somewhat depressing figure.

A month after she was charged at Westminster police court, Elvira’s trial at the Old Bailey commenced on 4 July 1932. Despite Hastings’ misgivings, she defended herself well, never once changing her story that it had all been a terrible accident. Her case was helped by the doctor who had first arrived at William Mews after the shooting when he said on the first day of the trial, ‘In her mental condition after the tragedy she could not have invented the story she told me. She seemed passionately devoted to the dead man.’ At the end of the trial Hastings made a final address to the jury, one that the judge – Mr Justice Humphreys – later called ‘the best he had ever heard’.

While everyone was waiting for the jury to return their verdict, Elvira, waiting to be summoned, was standing halfway down the stairs that led up to the large dock. The Daily Mirror described the scene: ‘She was ghastly pale and seemed as though she would break down completely. The two wardresses held her hands and she leaned heavily against the side of the stairs. The blood-vessels in her neck could be seen pulsating and throbbing as she ascended the steps.’ As soon as the jury arrived back in the courtroom, Hastings saw that they all glanced over at Mrs Barney. He knew that that was an almost infallible test that it would be a ‘not guilty’ verdict. When she heard that she had been acquitted, Elvira just stood in the dock looking intensely at Mr Justice Humpheys before she collapsed back into her chair. On his way out of the court the judge exclaimed, ‘Most extraordinary! Apparently we should have given her a pat on the back!’

After being found not-guilty, Elvira Barney arrives at her parents’ home at 6 Belgrave Square, London, 7th July 1932

The jury may have acquitted her, but Fleet Street weren’t in the mood to let her off so easily and they gleefully reported that Elvira Mullens (the name she had reverted to) had shouted on the dance floor of the Café de Paris soon after the court case, ‘I am the one who shot her lover – so take a good look at me.’ One strange aspect of this case was that Michael Stephen, the real victim, was always treated with an extraordinary lack of sympathy by both his family and the press. Sir Patrick Hastings was happy to describe him years later as ‘worthless’. During the trial the former attorney-general depicted Elvira as ‘a young woman with the rest of her life before her’. Unfortunately, the rest of her life lasted just four more years, and on Christmas morning in 1936 she was found dead in a Parisian hotel room after a typical long night of drinking and taking cocaine. It was reported that in the early hours she had decided to return to her hotel after complaining that she felt cold and unwell, and was last seen by a porter who had to help her up to her room. The next morning a chambermaid, after knocking several times, entered her room and found Elvira half on her bed, half off, and still dressed in a black and white checked dress and the fur coat she had been wearing in Montmartre the night before. She had been bleeding from the mouth. The years of drinking and drug-taking had finally taken their toll. Three days after her death the William Hickey column in the Daily Express described a recent meeting: ‘I last saw Mrs Barney in a Soho negro nightclub. It seemed her proper milieu. It is surprising to read that she was only 31. She looked ten years more, fat, with tired eyes. Her defiant, almost truculent manner suggested that she was miserably unhappy.’

At about the same time as Elvira’s untimely death in a small Parisian hotel room, the American singer Elisabeth Welch made her cabaret debut at the Café de Paris. She described the Coventry Street venue at the time as ‘the grand nightclub of London and all the big names of cabaret played there. It was very chic and very smart’. It was Welch, a year before Louise Brooks mesmerised audiences at the Café de Paris dancing to it, who had popularised ‘The Charleston’ in America when she sang the song inRunnin’ Wild on Broadway in 1923. She arrived in London eight years later with Cole Porter’s musical Nymph Errant. Soon she was singing in Ivor Novello’s Glamorous Night and had her own radio series called Soft Lights and Sweet Music. She rented a smart art deco house in a mews off Sloane Street. Elizabeth Welch was one of several black musicians before the war who enjoyed London and made it their home. Another was a man who will forever be associated with the Café de Paris because he died there: Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson.

Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson

The Café de Paris, unlike the majority of theatres and nightclubs in the West End, remained open at the start of the Second World War. The rich and famous patrons presumably had influence over the wartime licensing regulations, but it was always said that the dance floor was so far underground that it was completely safe in an air raid, a ‘fact’ that certainly wasn’t discouraged by Martin Poulsen, who called his Café de Paris ‘the safest and gayest restaurant in town – even in air raids. Twenty feet below ground’. In August 1940 the Nazi propagandist William Joyce, Lord Haw-Haw, sneered at the well-to-do having fun in the West End, broadcasting one night, ‘… the plutocrats and the favoured lords of creation were making the raid an excuse for their drunken orgies and debaucheries in the saloons of Piccadilly and in the Café de Paris … as the son of a profiteer baron put it, “They won’t bomb this part of the town! They want the docks! Fill up boys!”’

At 9.30 p.m. on Saturday 8 March 1941, Johnson was still having drinks with some friends at the Embassy Club in Old Bond Street. His show at the Café de Paris started at 9.45 so he half walked and half jogged the usual eight-minute walk to the Coventry Street nightclub – not easy in a blackout (blackout time that night was between 7.27 p.m. and 6.53 a.m.). By now sirens were sounding and an air-raid had begun, but he managed to get to the stage on time and the West Indian Orchestra started playing ‘Oh Johnny, Oh Johnny, How Can You Love’ as usual. Johnson was a striking front man, his nickname coming from the long-limbed elasticity of his eccentric dancing.

Time magazine a few weeks later described the audience that night as ‘handsome flying johnnies, naval jacks in full dress, guardsmen, territorials, and just plain civics sat making conversational love’. Five minutes into the song two bombs came crashing through the glass roof of the Rialto Cinema directly above the nightclub and exploded on the dance floor. Two days later The Manchester Guardian, after describing the bombing as ‘fairly heavy’ and careful not to name the Café de Paris because of wartime censorship, quoted a witness that night:

The band was playing and the floor was crowded with couples dancing. Suddenly there was a flash like the fusing of a great electric cable. Then in the darkness masonry and lumps of plaster could be heard crashing to the ground. I was blown off my feet, but the sensation was that of being pressed down by a great big hand. Several people switched on torches and others struck petrol lighters when they had recovered from the first shock. I could see people lying on the floor all around … The air was filled with smell of powder and dust.

Among the chaos, next to the microphone through which he had just been singing and with a red carnation still in the buttonhole of his white dinner jacket, lay the leader of the band. There was not a mark on his body but his head had been blown clean off. Ken ‘Snakehips’ Johnson, only twenty- six years old, had tragically reached the end of his meteoric career.

A special constable with the splendid name of Ballard Berkeley, who would later become famous as the actor who played the Major in Fawlty Towers, was one of the first on the scene. He saw the decapitated Snakehips and elegantly dressed people still sitting at tables, seemingly almost in conversation but covered in dust and stone dead. He was shocked to see looters, mingling with the firemen and the police, cutting the fingers from the dead to get at their expensive rings. The Manchester Guardian reported that a nurse who was helping the wounded ‘afterwards saw a man rifling her handbag. The articles stolen included a fountain pen and an RAF brooch given her by a pilot who is now a prisoner of war in Germany’. Among the dead was Mr Café de Paris himself, Martin Poulsen, and of the musicians, Dave ‘Baba’ Williams, a Trinidadian saxophonist, had been cut in half by the blast. Survivors included the Grand National winning jockey and horse-racing trainer Fulke Walwyn, the author Noel Streatfeild (aka Susan Scarlett), and Howard Barnes, an advertising copywriter who lost his leg in the blast but who later became a songwriter (Nat King Cole recorded his ‘A Blossom Fell’).

London: Cafe De Paris Pictured In 1941 After It Was Bombed During World War Ii.

Air Raids over Britain during World War II

The Blitz on British cities – The attacks started on September 7th 1940 and continued to May 1941.

Three years after the Café de Paris explosion, a house on Rutland Street, a few hundred yards away from William Mews, was razed to the ground by a V1 flying bomb. It was the home of Marion Harris, who had by then retired from show business after marrying a theatrical agent called Leonard Urry. Not that he had been a theatrical agent for long. When Harris first met Urry he was employed as a professional ‘dance partner’ at the Café de Paris. He was paid, essentially, for dancing with women who were on their own or had no one to dance with. Some might have called him a gigolo. Harris was completely traumatised by her home being destroyed and she soon returned to America. She never really recovered and she was soon admitted to a neurological sanatorium. Within a few weeks of her arrival in the US, on Sunday 23 April 1944, her room at the Hotel Le Marquis in Manhattan caught fire. She had fallen asleep with her cigarette still burning and the cause of death was asphyxiation and terrible burns.

Princess Margaret Cafe de Paris 1955

After the explosion that killed Snakehips Johnson and about eighty others (the exact number isn’t known), the Café de Paris remained closed throughout the Second World War. After a refurbishment in 1948, the famous West End nightclub reopened. It was again graced by royalty, notably Princess Margaret, the niece of the former Prince of Wales, and, although it came close, the club never really regained the sophisticated aura that it had garnered before the war. The only notable exception was on 29 September 1965, forty years after Louise Brooks danced at the Café de Paris with such acclaim, when Lionel Blair launched his new dance called ‘The Kick’ at the same venue. It wasn’t a storming success.

This is an excerpt from Rob Baker’s acclaimed book Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.