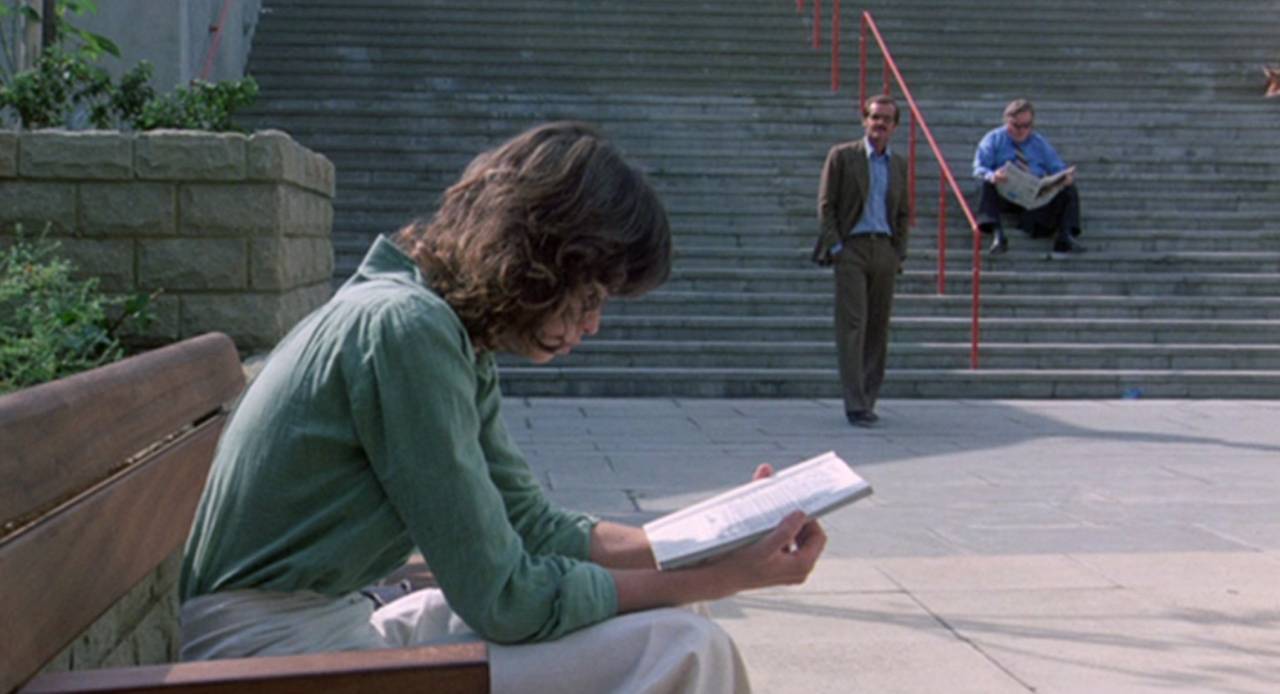

At about half an hour into Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1975 film The Passenger, Jack Nicholson is seen walking across a large paved concourse before jauntily tripping down a wide concrete staircase. We can see it’s part of long, concrete, modernist structure and the short scene was filmed in Bloomsbury at the recently completed Brunswick Centre – a relatively low-rise housing, office and retail ‘megastructure’ designed by the London architect Patrick Hodgkinson.

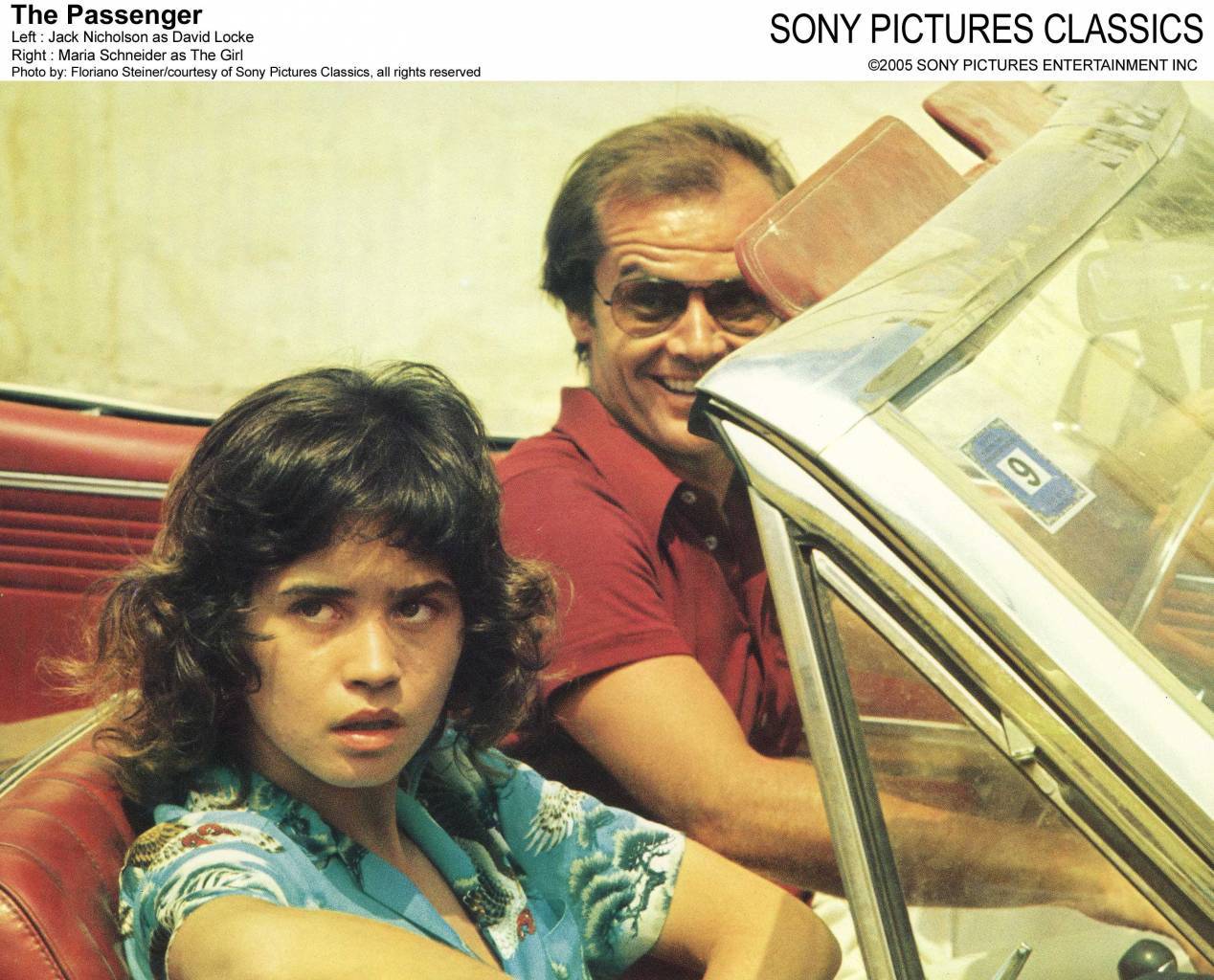

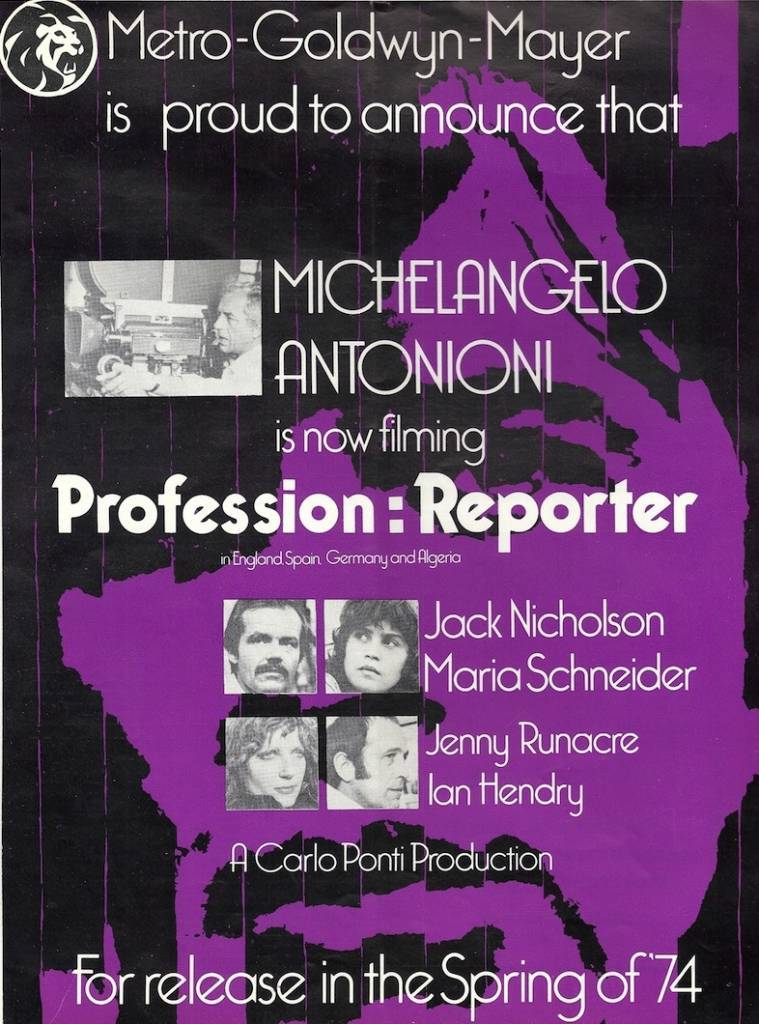

The Passenger or Profession: Reporter, as it was originally to be called, was the last of three English-language films (the others were Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point) Antonioni made for MGM. It has been said by many that Nicholson was at his charismatic best – the late Roger Ebert described him in the film “as attractive and understated as he has ever been.” This may or may not have had something to do with the direction he received from Antonioni, not overly keen on the method-acting style, during the filming: “Jack, fewer twitches”.

The American actor plays a disaffected English journalist called David Locke, who at the start of the film, set initially in North Africa, finds a dead man called Robertson in the next door room. Wanting to desperately escape his own problematic life Locke assumes Robertson’s identity – “I used to be someone else, but I traded him in.” He swaps the photos in their passports, switches their clothes and tells the hotel of the dead man in his hotel room. In London, both his office and his wife think he’s dead. Locke takes Robertson’s diary and decides to keep his appointments around Europe.

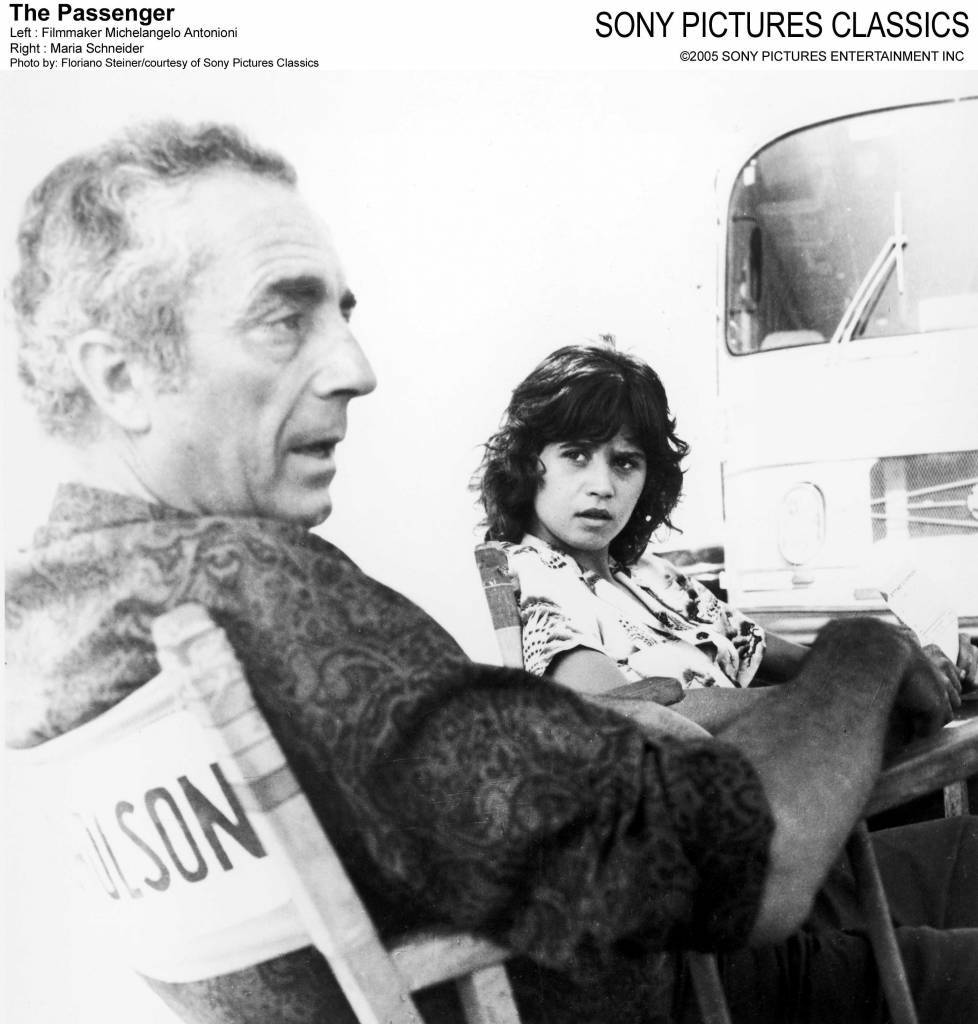

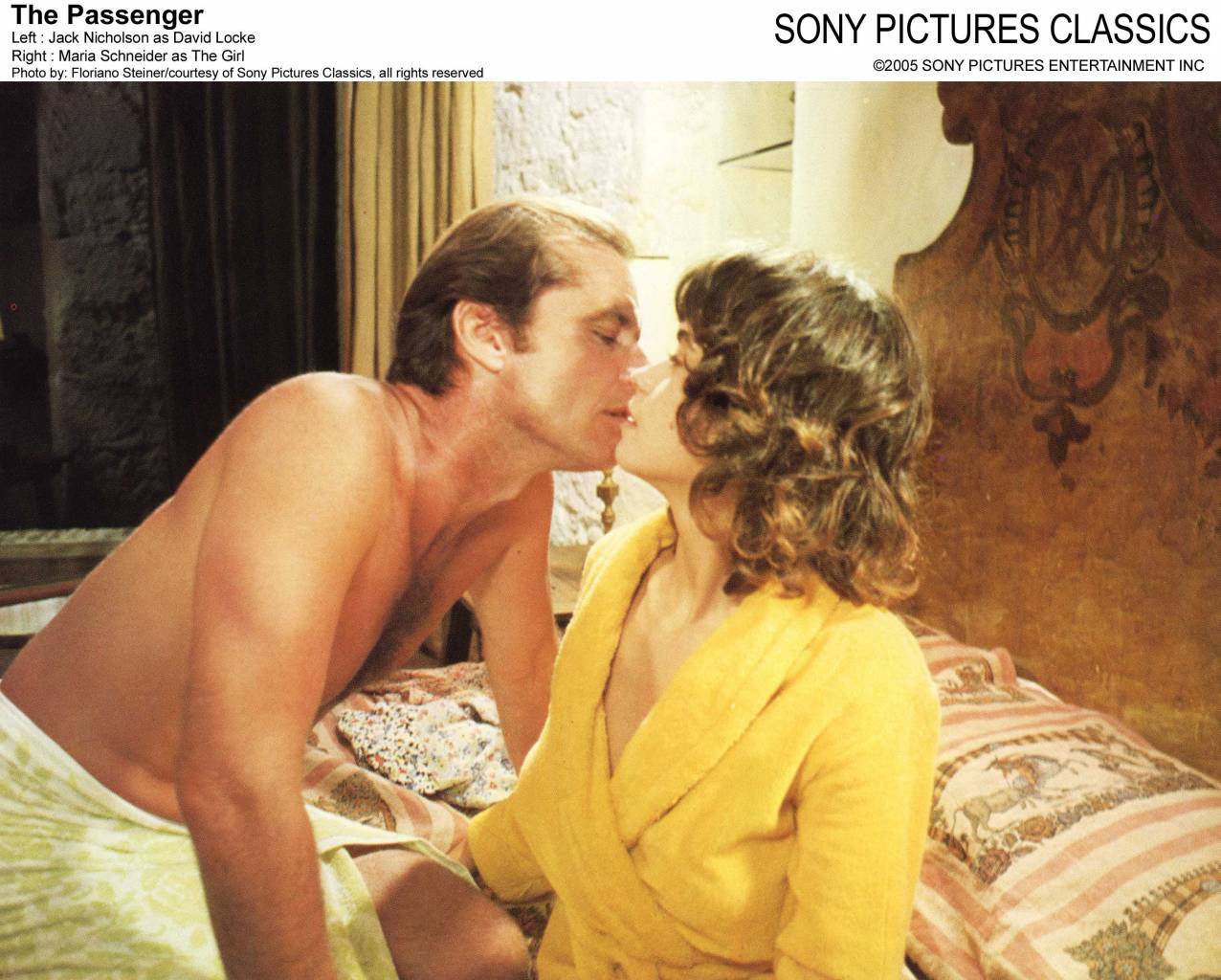

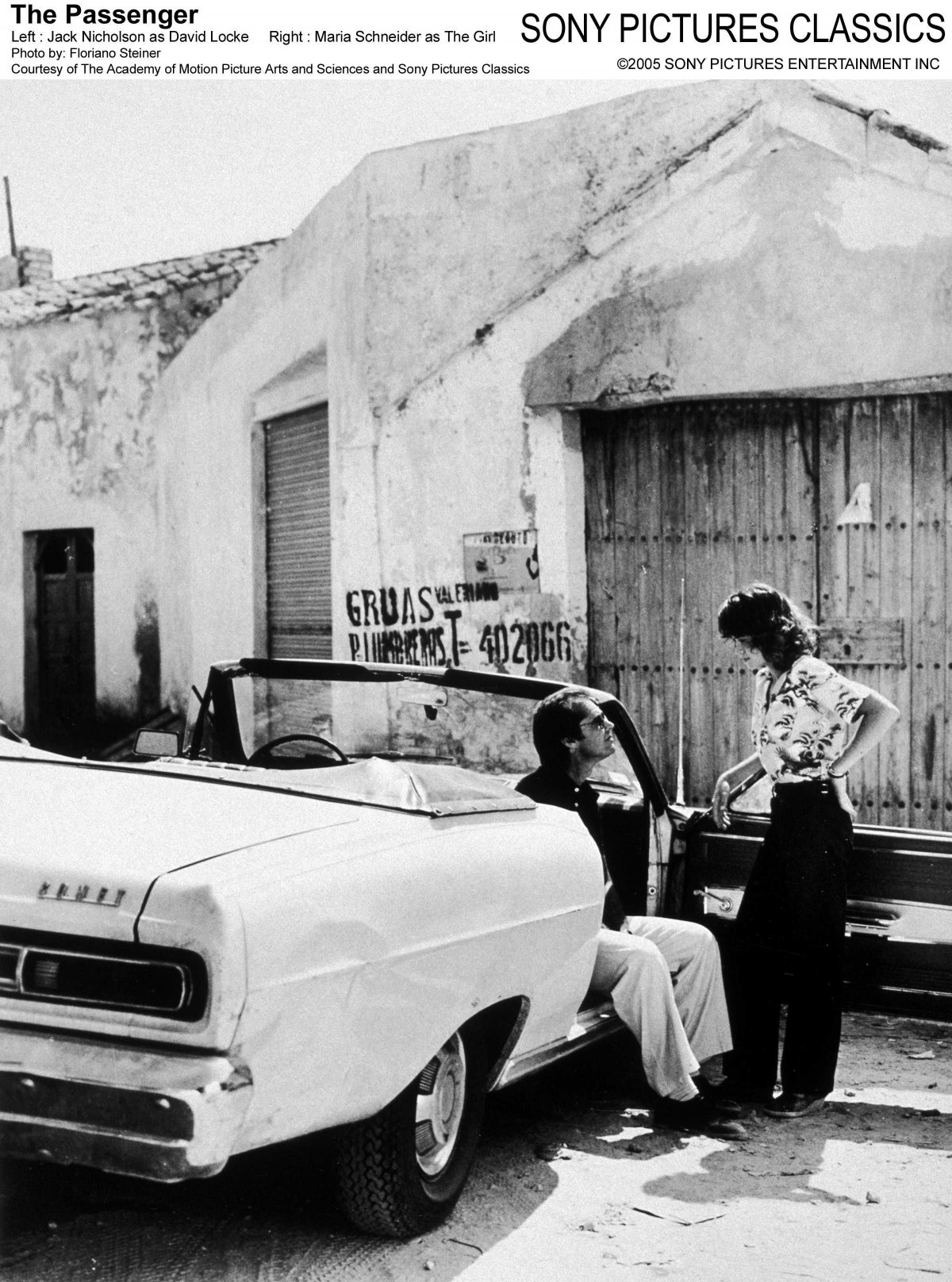

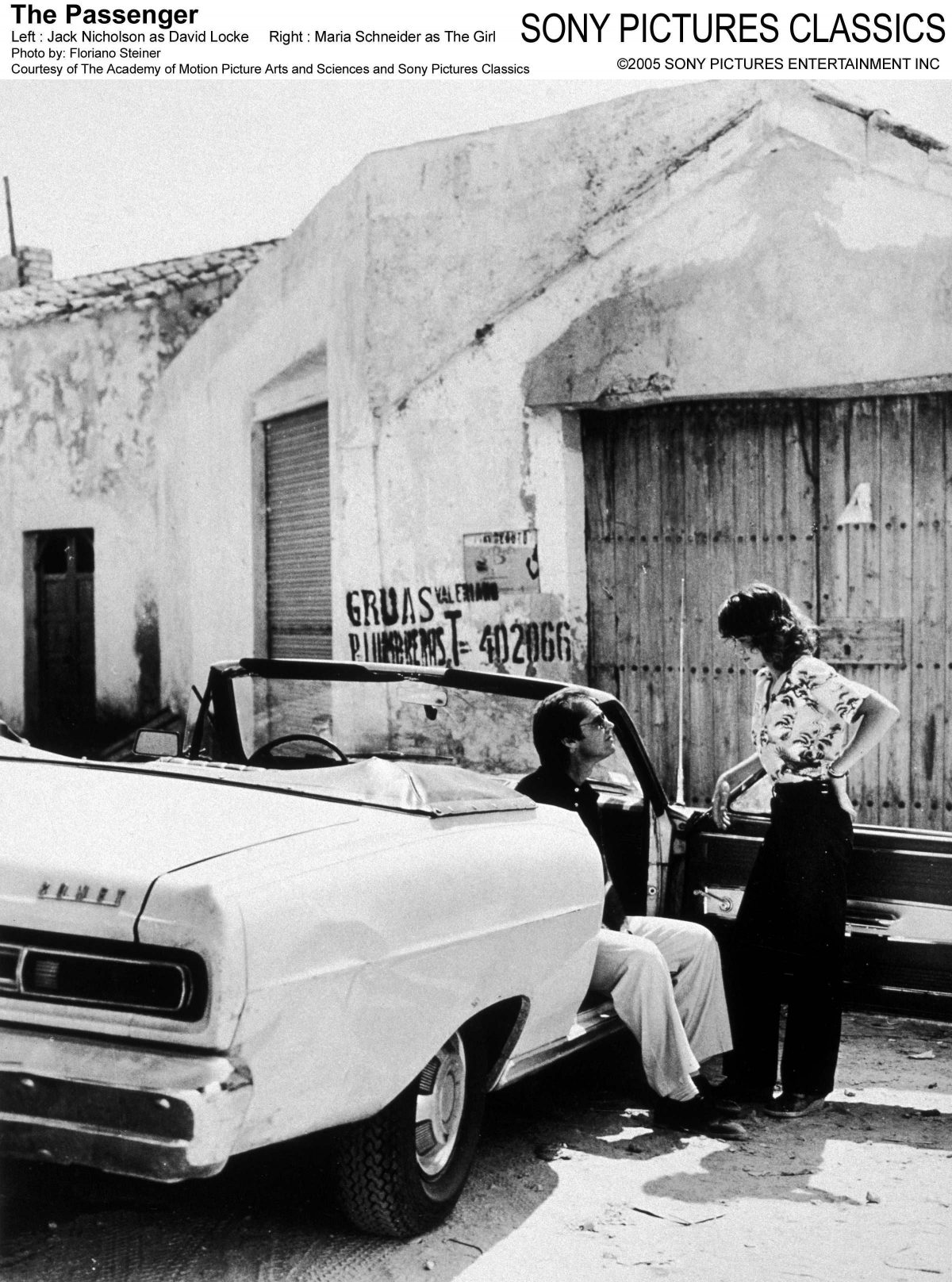

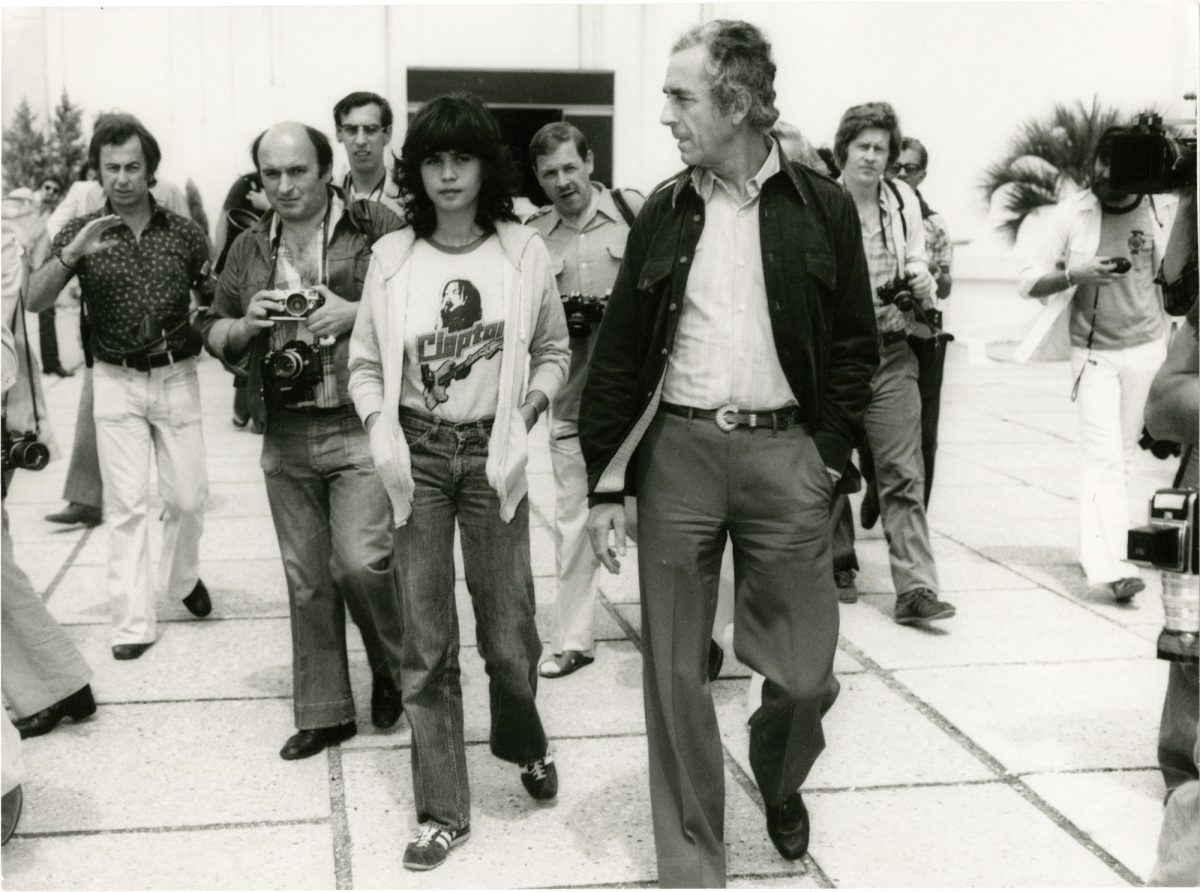

Locke’s first stop is at the Brunswick Centre where he notices an un-named woman reading and sunning herself at the bottom of the staircase. Destined to become his companion in the film she’s played by Maria Schneider who at the time was the European art-film darling after appearing in Last Tango in Paris. Bertolucci, in his film, was kind enough to give her character the name Jeanne, whereas in The Passenger, rather dismissively, she is credited as just “The Girl”.

10th August 1973: The Brunswick Shopping Centre in Bloomsbury, London. (Photo by Peter King/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

The wide concrete staircase has now gone in fact demolished not long after the film was released by Camden Council citing security reasons for its tenants. But even the word ‘Centre’ is no more and the building, for a reason only known to some over-paid image consultants, now sounds like a pub and is known just as ‘The Brunswick’.

Patrick Hodgkinson started drawing up plans for the proudly avant-garde development of shops and apartments as far back as 1959. It was designed to replace much of the Foundling Estate – a residential area established in the 18th century to provide rent as income for the nearby Foundling Hospital (demolished in 1926). He based his work on studies for low-rise, high density architecture initially made by Sir Leslie Martin who in 1953 had become the Chief Architect of the London County Council. Martin had been responsible for the Royal Festival Hall and also the Loughborough Estate in south London. Hodgkinson’s initial designs, however, also owed a lot to Sant’Elia’s sketches for a futurist city but he was also influenced by Bruno Schlaffenberg, an italian planning officer for the L.C.C. and subsequently Camden Council. Schlaffenberg thought that people should live close to their places of work and disliked the idea of wholly residential estates such as the Hampstead Garden Suburb built in 1906, once seen as an architectural model, but had no shops or places of employment.

Like much of central London Bloomsbury had been badly affected by the wartime bombing but it perhaps seems odd today that the L.C.C. was happy to blithely knock down an historical and handsome Georgian terrace. It is worth remembering, however, that Leslie Martin was responsible for detailed plans, supported by many senior members of the Government during the early sixties, that would have razed and rebuilt the whole area of the capital from Downing Street to Parliament Square while cutting a grand axis through two miles of Central London to connect Whitehall with the British Museum.

After the war, for obvious reasons, most new housing development was for the benefit of those who were unable, or could not afford, to house or rehouse themselves. The Brunswick Centre was always meant to be something different. Hodgkinson had been asked to create urban housing for the middle classes, most of whom since the war had been moving out to the wealthier suburbs. Additionally the L.C.C. wanted a new centre for Bloomsbury which although still famous for its glamorous, literary connections was now a shadow of its former, self-assured self.

Hodgkinson’s original scheme proposed expensive shops and lots of underground parking to go with the housing. The Buchanan report entitled ‘Traffic in Towns’ commissioned, in 1960 by the Conservative Transport Minister Ernest Marples was becoming extremely influential all over Britain. It encouraged the opening up of cities to hitherto unimaginable levels of traffic but also recommended that urban planning should change its outlook completely. Shops, for instance, rather than facing onto traditional vehicular roads, should face onto pedestrianised streets with multi-storey parking nearby. Urban areas should be on multiple levels with traffic moving underneath a concourse with pedestrian walkways and contrasting open squares containing fountains and artwork.

By 1962 the L.C.C. still had to grant the ten acre area (which consisted of about 250 properties including 60 small hotels and boarding houses) planning permission citing that too many offices were included in the designs and that the density of the residential part of the plans was problematic. Design changes were made but in 1965 Hodgkinson’s scheme was only saved when Camden council signed a 99-year lease on the housing. Construction started two years later but due to a change in legislation, the buyer of the Foundling Estate portfolio hadn’t reckoned on paying compensation to the tenants of the run-down Georgian houses that were to be demolished. The ownership of the project was transferred to the property developer Robert McAlpine and the range of flats was reduced from sixteen types to three. Originally the plans had a wide range of different sizes from luxury apartments to flats for professional workers but they also included hostels for young medics and nurses who would be working near by. In 1969, and after ten years of dedicating his life to one major project, and unhappy Hodgkinson was forced to resign. He would later say:

It had been intended for quality retailers but as soon as people heard it was going to be council housing they all ran away.

The completed building certainly wasn’t universally admired. The Observer’s architect correspondent Stephen Gardiner didn’t mince his words when he described the building’s interior as: “the nearest thing to a prison atmosphere in the free world… Inside, in particular, there is this grim, puritanical and seemingly endless perspective view through a cobweb of concrete colonnades.”

The Brunswick Centre we see in The Passenger hardly looks grim and puritanical – although it was shot outside on a sunny day and the concrete looks bright and new. The reason why Nicholson’s David Locke suddenly appears in Bloomsbury isn’t really explained in the film except that the massive modernist building gave Antonioni another of his archetypal brutalist backgrounds. In the opening scenes of his 1966 movie ‘Blow Up’, for instance, he used the acclaimed Economist Building on St James’ St designed in 1962 by Alison and Peter Smithson (also former disciples of Leslie Martin).

One of the main themes running through much of Antonioni’s work is the human experience of emptiness and alienation. Locke’s feeling of inconsequential irrelevance (enough to try out somebody else’s life) is only highlighted by the enormous architecture he moves through. The Observer’s Stephen Gardiner, still upset with the Bloomsbury development, wrote, not without some truth, that the Brunswick Centre had ‘a curious air of placelessness’. This is similar, maybe not coincidentally, how Antonioni’s films are also described. Richard Sennett in his book ‘The Fall of the Public Man’ agreed with the Observer critic when he wrote:

[The Brunswick Centre] is sited as though it could be anywhere, which is to say its siting shows its designers had no sense of being anywhere in particular, much less in an extraordinary urban milieu.

In The Passenger when “The Girl” joins Locke on his travels she realises he hasn’t any particular place to go, and asks him, “What are you running away from?” Nicholson answers her by saying “turn your back to the front seat.” When she does and sees the road just stretching out behind them into the distance, she just laughs.

Patrick Hodgkinson always intended the Brunswick Centre’s concrete to be painted cream in homage to the Georgian terraces that the building replaced. Camden Council never quite got round to this and the building, as foreseen by Stephen Gardiner, soon turned shabby and grey. By the 1980s, with more than a few of the retail units empty and unused, the Brunswick Centre was considered by many as nothing more than a central London example of outdated Brutalism and sixties urban planning that had no relevance to its surroundings.

Even today it is still shocking to see the rear of one of the Brunswick Centre’s solid concrete apartment blocks built right up against, and disdainfully ignoring, the adjacent and beautiful Brunswick Square. Richard Sennett continued:

Everything has been done to isolate the public area of Brunswick Centre from accidental street incursion, or from simple strolling, just as the siting of the two apartment blocks effectively isolates those who inhabit them from street concourse and square.” In an interview with Time Out magazine, Hodgkinson defended his ideas by saying: “Bloomsbury was miserable in the sixties – the Georgian buildings were all in an awful state. We weren’t allowed to build higher than 80 feet, but we still achieved the maximum density allowed…I became known as a Brutalist, but I wasn’t at all.

In the 1990s Hodgkinson got involved again with his architectural baby when new developers approached him to work with them on its refurbishment. He in turn invited two of his original team, David Levitt and David Bernstein of Levitt Bernstein, to work on the major facelift. The developers at last rendered and painted the concrete ‘Crown Commissioner’s Cream’ exactly as Hodgkinson had originally intended. The building is now more like the ‘superblock with shops’ he had originally envisaged in 1960. The two bedroom apartments (no longer called flats of course) are selling for six or seven hundred thousand pounds these days.

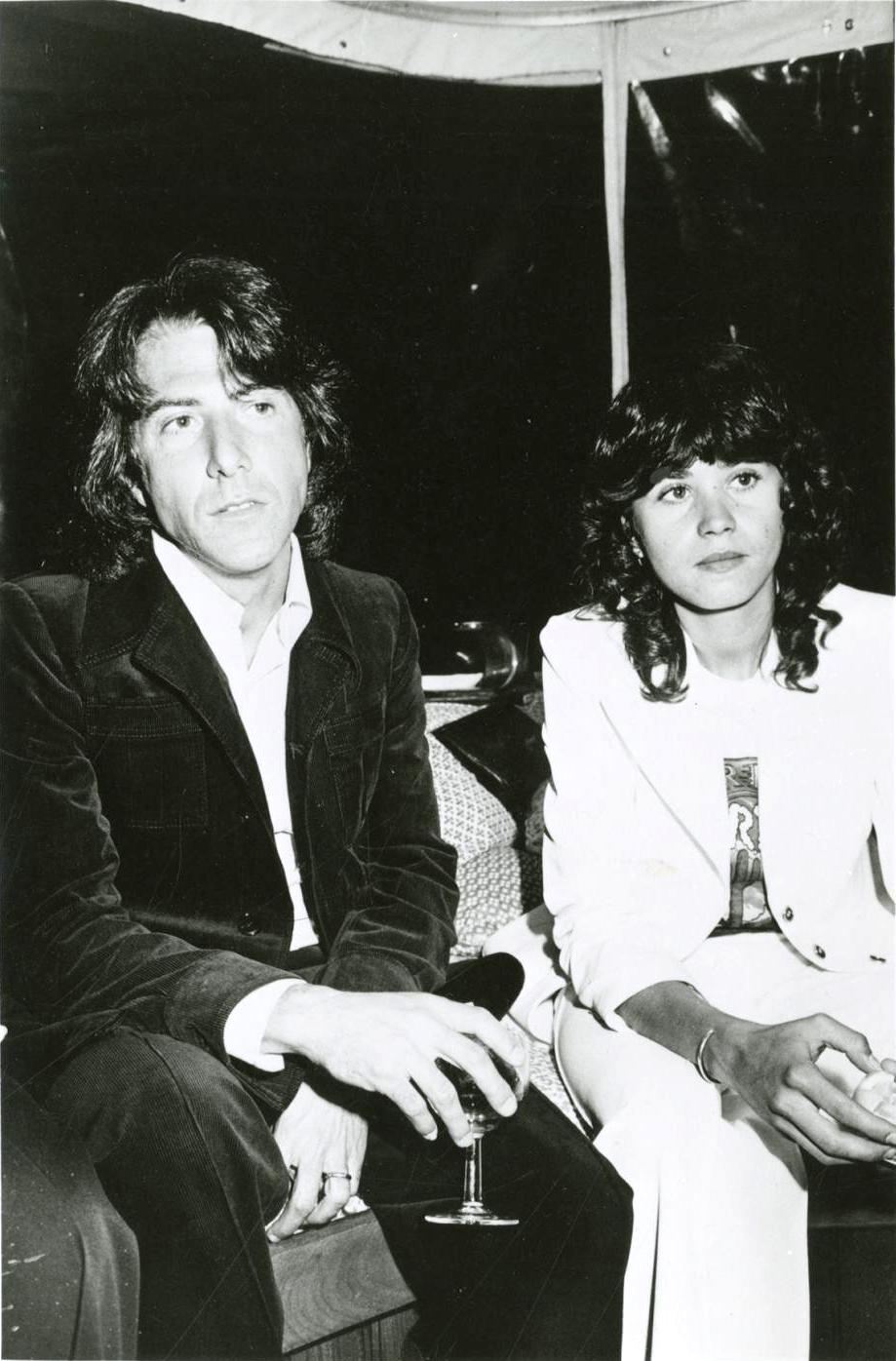

Maria Schneider and Nicholson in the Passenger

Maria Schneider and michelangelo Antonioni promoting The Passenger at Cannes 1975

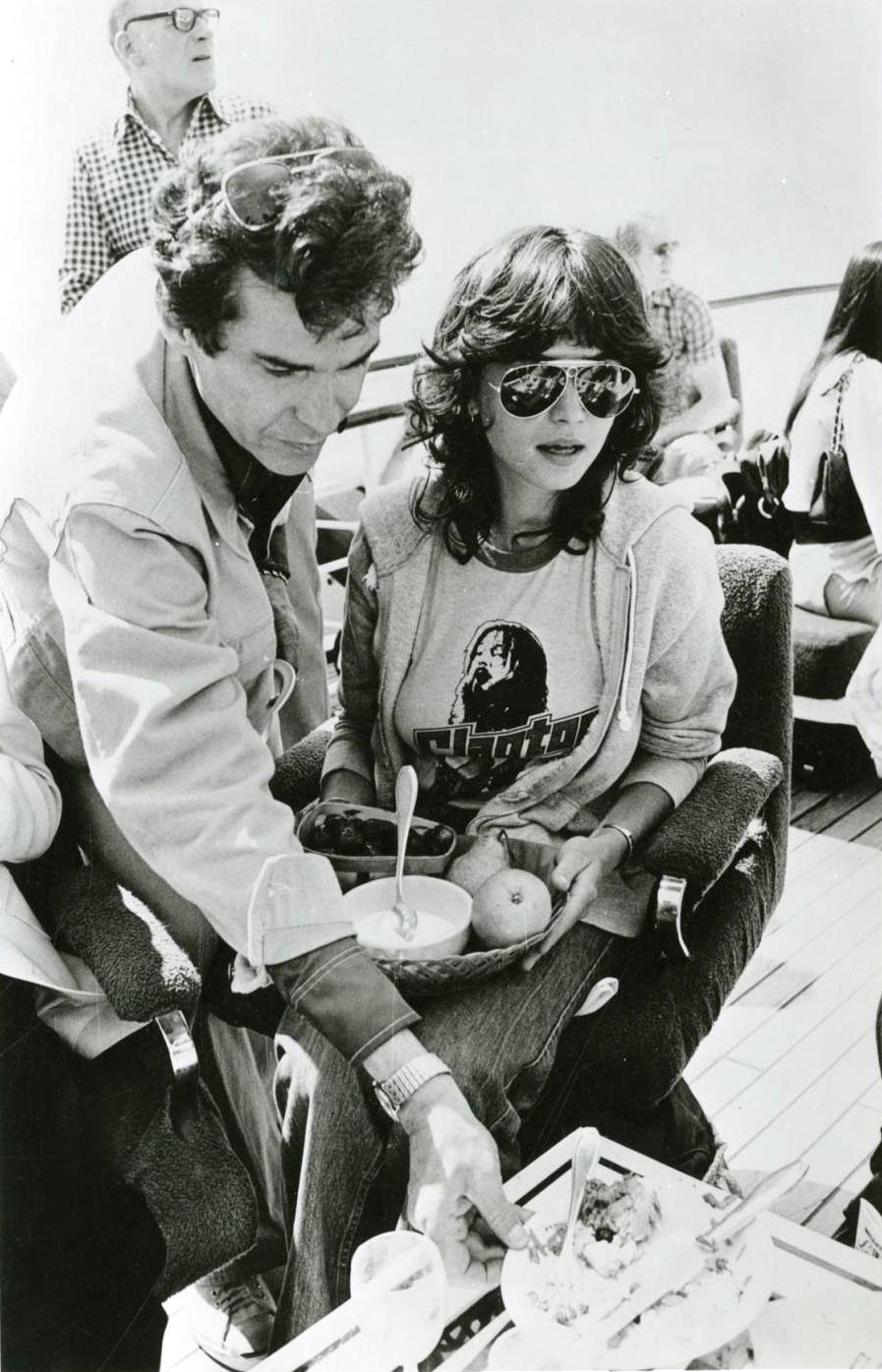

Dustin Hoffman and Maria Schneider at Cannes 1975

Maria Schneider at the Cannes Festival 1975

Maria Schneider and Antonioni at Cannes 1975

Maria Schneider and Antononini at Cannes 1975

J. Hoberman of the Village Voice reviewed The Passenger thirty years after it was initially released and wrote that, “[it] looks better now than it did then, in part because it’s so clearly dated’. The same thing, of course, can be said of The Brunswick Centre – fashion is like that – and it is now a Grade II listed building. The Brunswick, as I suppose we must now call it, features expensive Chinese granite paving and a long water feature by ‘SPACE artist’ Susanna Heron that runs along its internal street. The shops have changed too. When it first opened there was a Wimpy bar on the ground floor, a mostly empty ‘discotheque’ in the basement and a small scruffy Safeway’s. Now it’s Space NK, Hobbs and Carluccio’s. The supermarket has gone upmarket too, and increased in size. If Antonioni was shooting the same scene today and in the same spot (which of course he wouldn’t as there is nowhere near the right sense of emptiness and alienation these days) Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider would almost certainly miss each other amongst the lunchtime crowds queueing for their quinoa salads in the largest Waitrose in central London.

It’s said that most of the apartments that come up for sale in the Brunswick these days are bought by architects and designers. The late Reyner Banham was prescient in his 1976 book Megastructure, Urban futures of the Recent Past, when he described the Brunswick Centre as: ‘The most pondered, most learned, most acclaimed, most monumental, most bedevilled in its building history of all English megastructures — and seemingly the best liked by its inhabitants’.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.