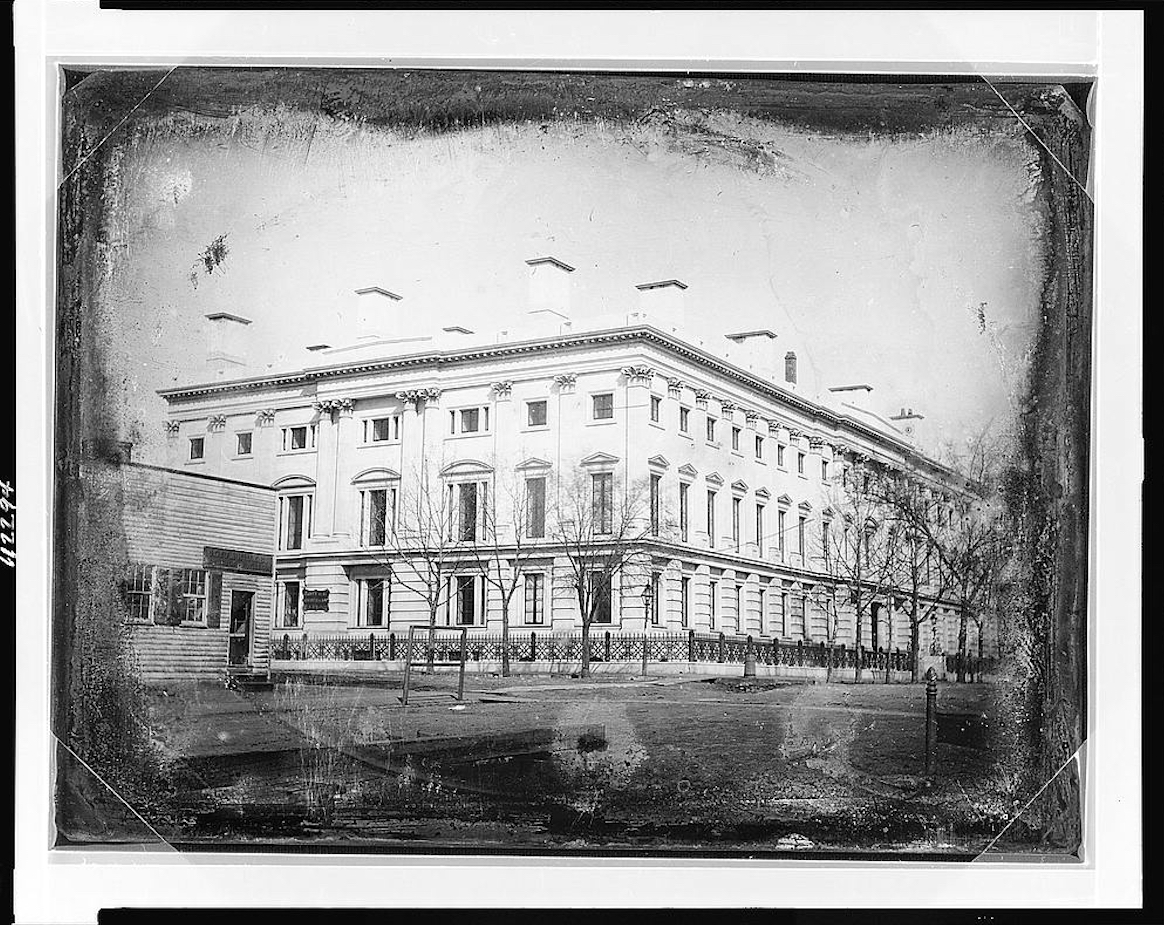

The President’s House, 1846

It can be difficult for historians to confidently declare a photograph a “first” when it comes to daguerreotypes. The process that bears its inventor’s name had only a short-lived heyday—from the early 1840s to the mid-1850s. Then it was superseded by other, more convenient, photographic methods. Daguerreotypes were unique images and had no negatives. They were hard to preserve, though they “could be copied,” the Library of Congress explains, “by redaguerreotyping the original” or “by lithography or engraving.” But many firsts were simply lost to time.

The ephemeral nature of daguerreotypes hardly presents a problem in the digital age, when the surviving images can be scanned and reproduced infinitely. Now, these photos offer unique historical perspective to anyone with online access. The images taken by daguerreotypist and Welsh immigrant John Plumbe, Jr. open a window onto a pivotal time in American history, as the country pursued its plans for westward expansion under the doctrine of Manifest Destiny articulated in the 1840s and named in 1845 by newspaper editor John O’Sullivan.

The U.S. Capitol Building, 1846

In 1845, president James K. Polk took the oath of office, a few months after Plumbe opened his new Daguerreotype gallery in Washington, DC, “in the Concert Hall building next to the fashionable Brown’s Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue,” Clifford Krainik writes at the White House History Association. “Ever seeking the carriage trade, Plumbe located his daguerreotype studio halfway between the Capitol and the President’s House. It was probably not by accident that his arrival in Washington coincided with that of President-elect Polk.”

Plumbe had no competition when he first opened his studio. It was the first in the nation’s capital. He did not, however, first set out to become a photographer but to aid the country in establishing its empire in the west. A civil engineer by training, Plumbe originated the idea of the transcontinental railroad. When he was unable to get a commission for the survey, he turned to daguerreotypy to make money. By 1846, he had been dubbed “the American Daguerre” and operated 13 studios around the country, including galleries in Boston and New York. Once set up in DC, he made it his mission to be the first to photograph a sitting president and his cabinet.

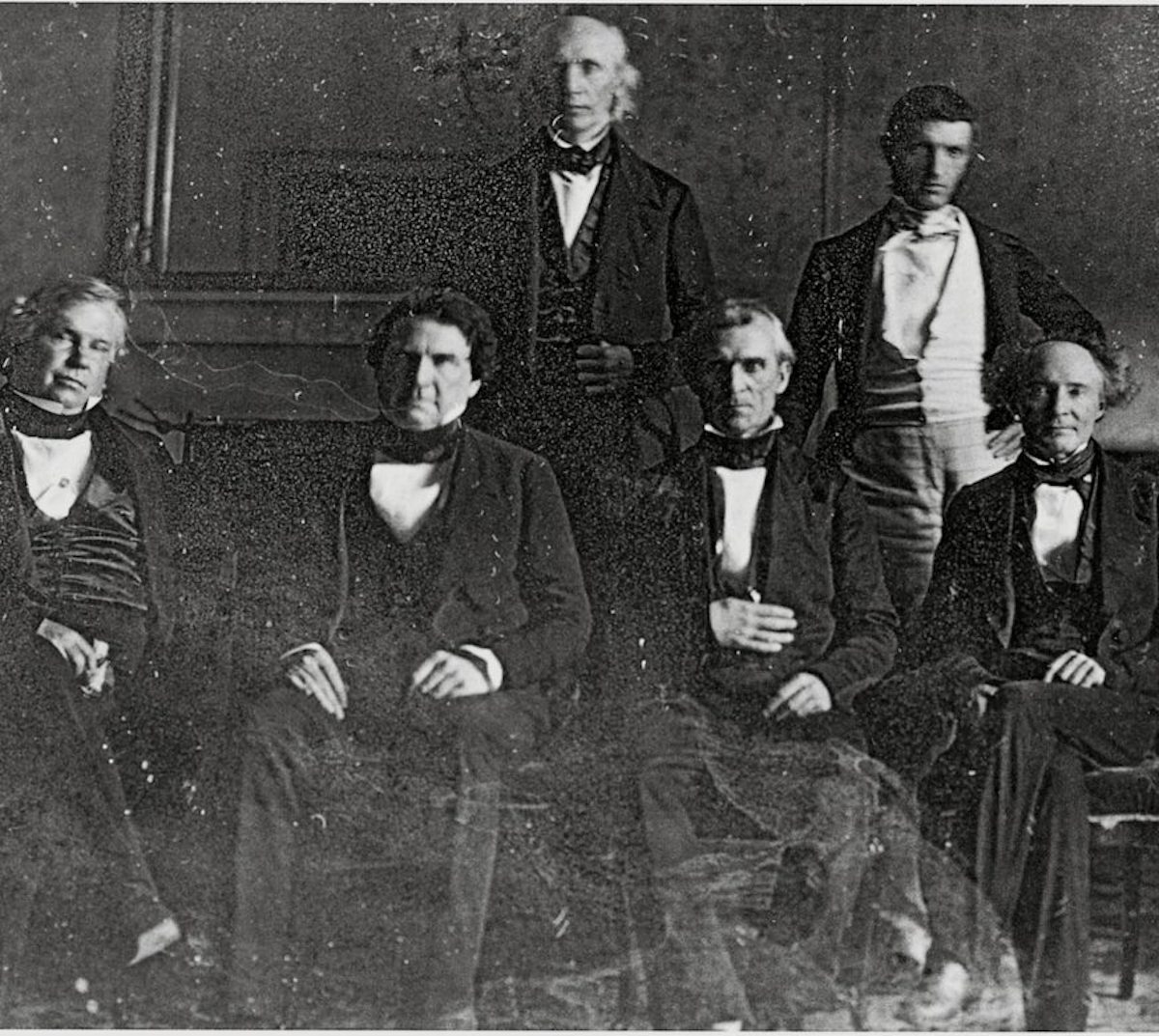

President James K. Polk and his Cabinet, 1846

The photographer accomplished this goal in the image above (Polk is seated second from right) in the spring or summer of 1846. “By that time Polk had assumed the role of commander in chief of all U.S. Military forces and was conducting a distant war” against Mexico after the annexation of Texas, Krainik writes. Plumbe also took what would become the earliest surviving image of the President’s House—later known as the White House—at the top of the post, and he made daguerreotypes of other famous capital buildings, such as the U.S. Capitol itself, further up, with its early Charles-Bullfinch-designed dome before a redesign in the 1850s.

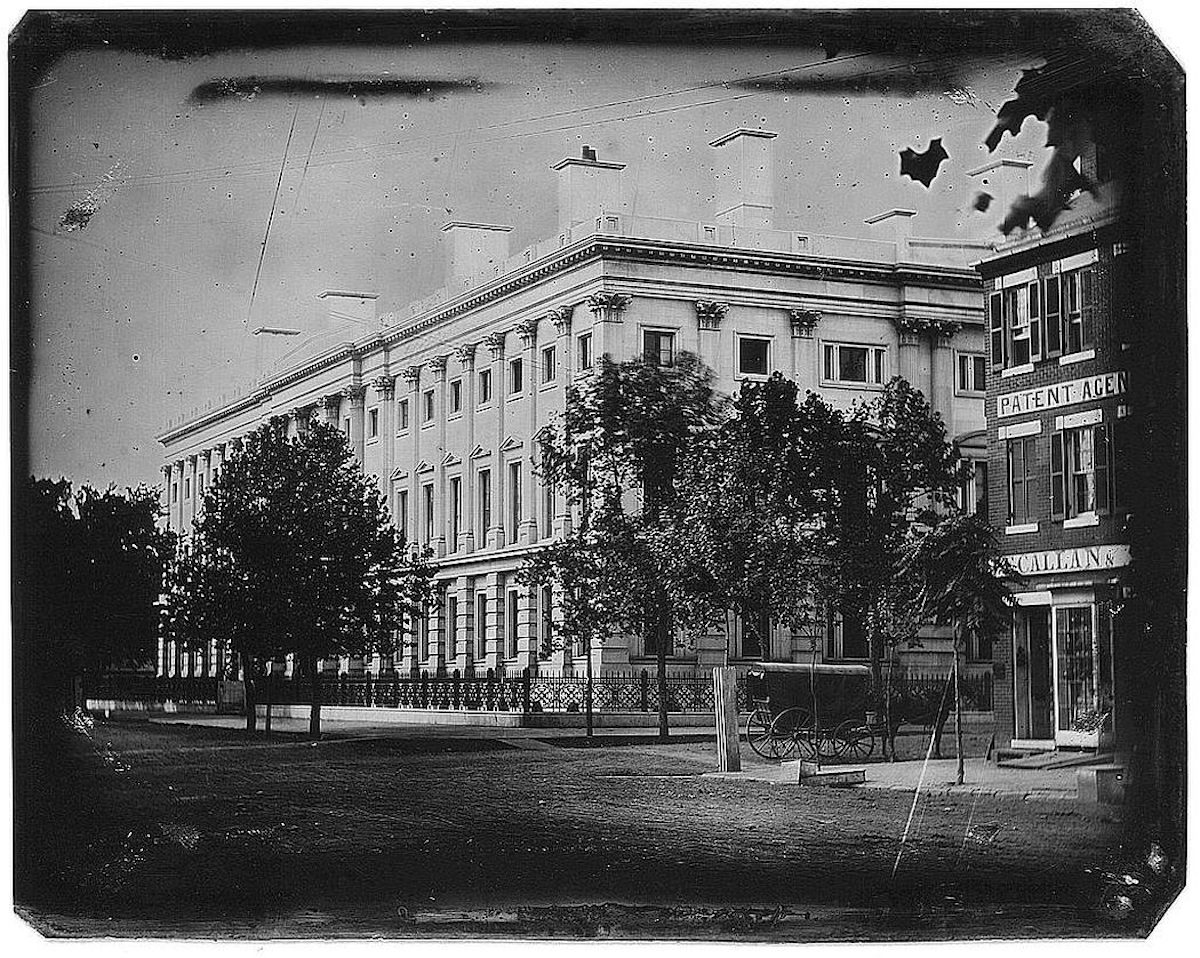

Plumbe’s time in DC produced photographs of the General Post Office (now the Kimpton Monaco Hotel), seen in two different angles, below, and the U.S. Patent Office, further down. His photograph of the White House may not be the “first” such image, but it is the earliest surviving, and it is the reason “historians still know what the president’s residence originally looked like,” Monovisions points out. Soon afterward, the United States Journal wrote, “We are glad to learn that this artist is now engaged in taking views of all the public buildings which are executed in a style of elegance, that far surpasses any we have seen.”

U.S. General Post Office Building, 1846

U.S. General Post Office Building, 1846

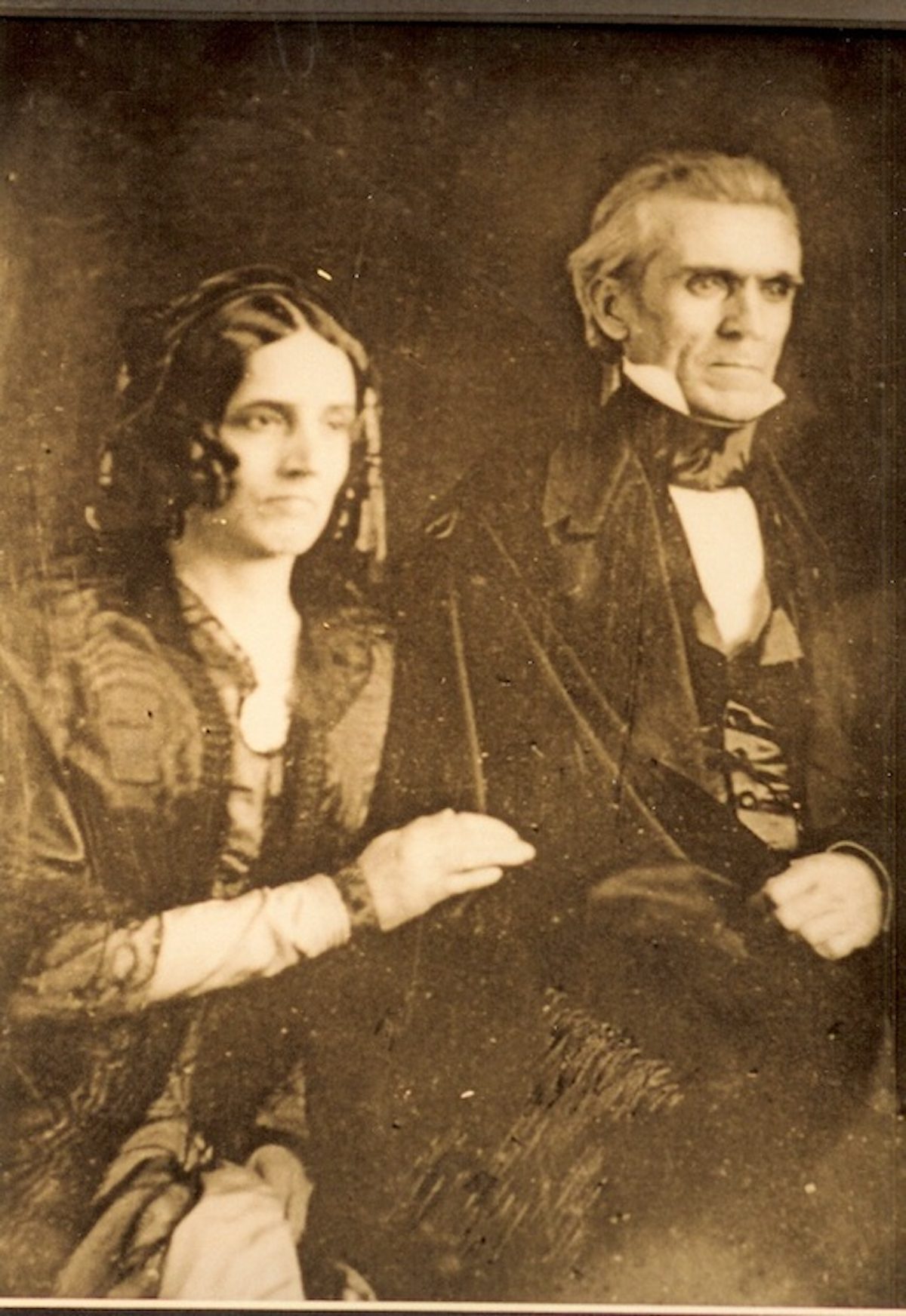

Plumbe was not the first to photograph a sitting U.S. president. That honor falls to the itinerant photographers Moore and Ward, who captured William Henry Harrison in 1841, possibly on the day of his Inauguration, just a month before he died of typhoid. But this image has never been found, which leaves Plumbe as the creator of the earliest existing such photo, or photos, since he took “several good likenesses” of Polk (see him with his wife above), as the president himself recorded in his diary. Plumbe also took a few portraits of former president John Quincy Adams around that time.

U.S. Patent Office, 1846

Plumbe was a first in other important ways as well: The success of his business model spread far and wide. Of course, he did not take all of the photographs himself, but “it was a policy of the Plumbe Gallery,” writes Krainick, “that all of the daguerreotypes issued from its many locations (regardless of the photographer) were identified as works by PLUMBE. Plumbe pioneered the concept of brand name recognition in photography. Mathew Brady would copy the idea to great advantage ten years later.”

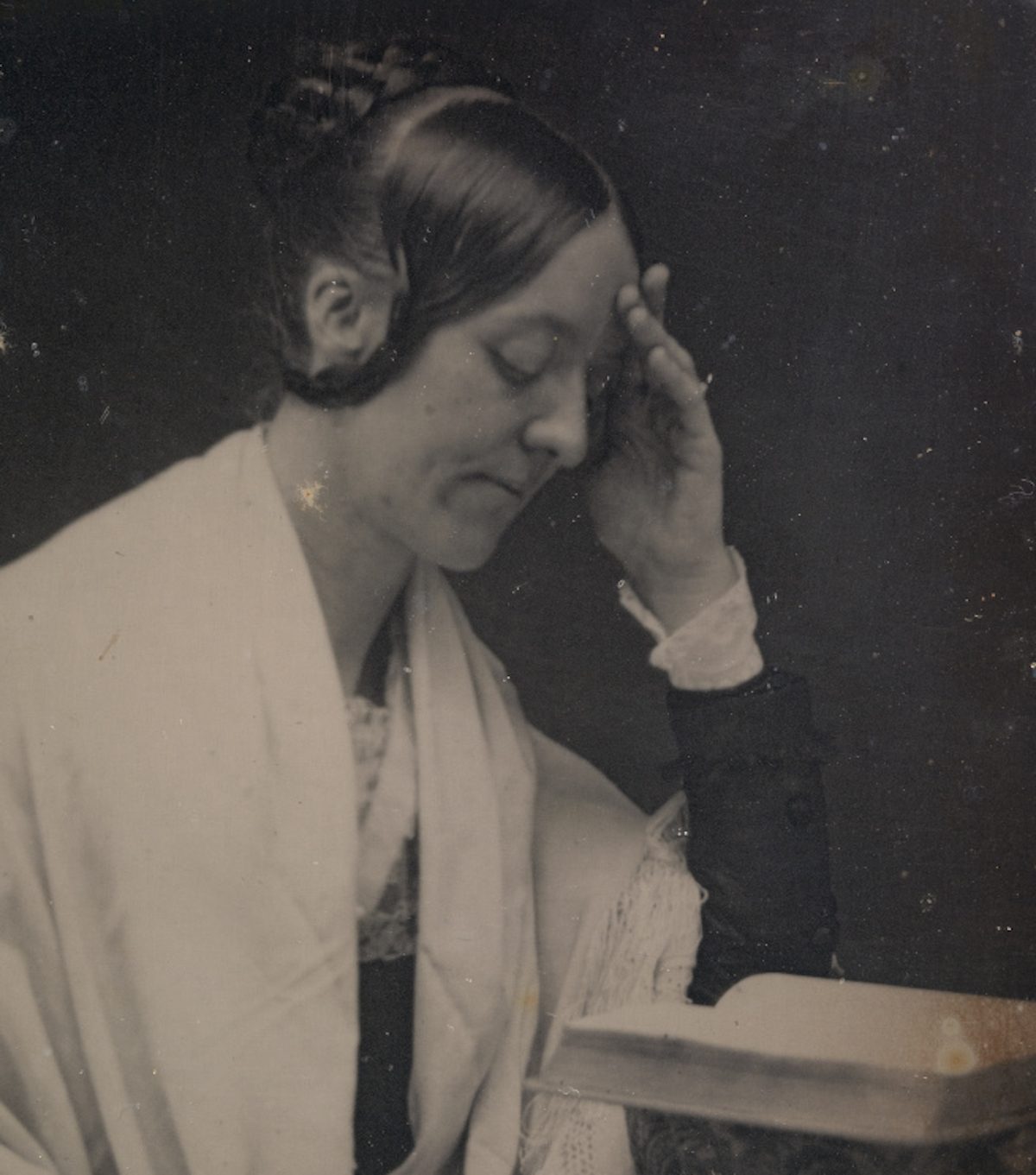

Sought after by the famous and non-famous people alike, Plumbe, or as his associates, would also take daguerreotypes of writers Washington Irving, Margaret Fuller, and (possibly) Walt Whitman, and of Samuel Ringold, the so-called “father of modern artillery,” who died in 1846. Plumbe himself would not survive the following decade. In 1857, after he sold his business to his employees and retired to Dubuque, Iowa, “he met an untimely end,” the J. Paul Getty Museum writes,” by cutting his own throat.” See more of his daguerreotypes online at the Getty and the Library of Congress.

Former President John Quincy Adams, 1846

Samuel Ringold, 1846

Washington Irving, 1855

Margaret Fuller, 1846

James and Sarah Polk, 1846

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.