Before me floats an image, man or shade,

Shade more than man, more image than a shade;

For Hades’ bobbin bound in mummy-cloth

May unwind the winding path;

A mouth that has no moisture and no breath

Breathless mouths may summon;

I hail the superhuman;

I call it death-in-life and life-in-death.– William Butler Yeats, Byzantium

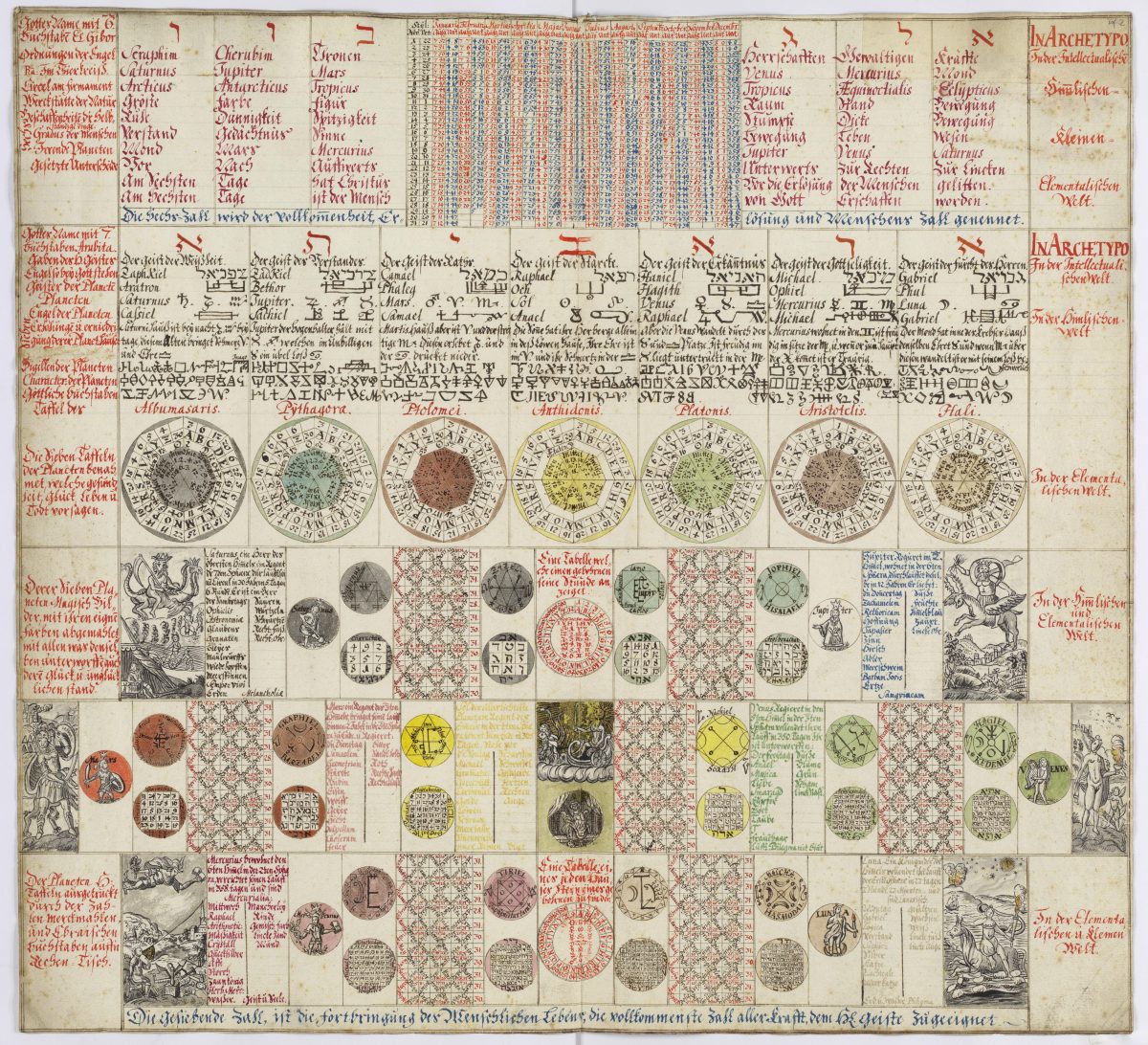

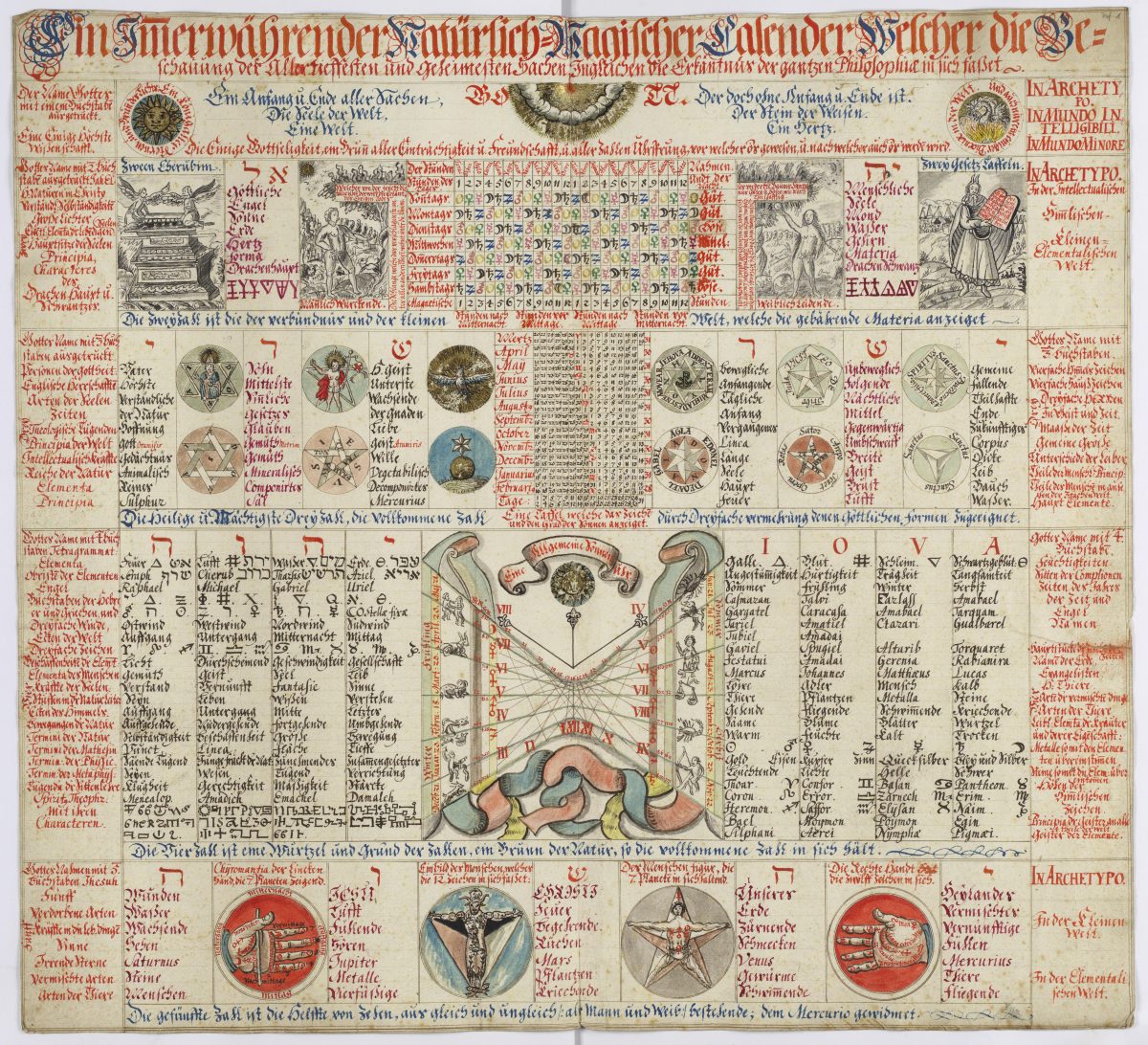

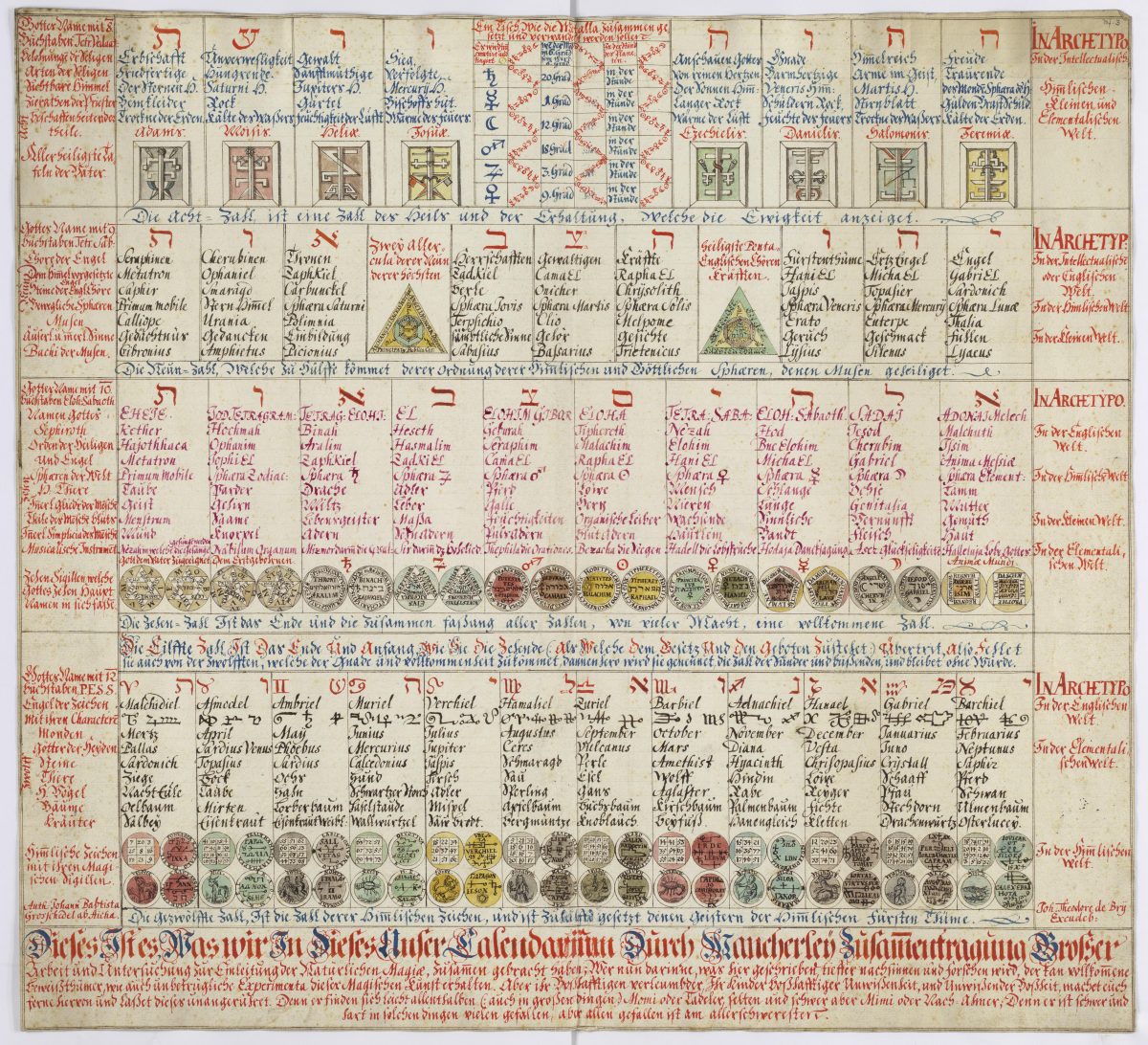

The three charts mapping out paths to revealing the hidden through magic are from the 16th Century German book ‘An everlasting natural-magical calendar, which contains the contemplation of the deepest and most secret things, as well as the acknowledgments of the whole philosophy’. (Original title: Ein Im[m]erwährender Natürlich-Magischer Calender, Welcher die Beschauung der Allertiefesten und Geheimesten Sachen, Ingleichen die Erkäntnüs der gantzen Philosophie in sich faßet.)

Published in 1582, although others say it was first printed around 1620, the work features the three large tables of celestial and magical correspondences you see here.

In seeking to explain everything, the artist – given as Johann Baptist Grossschedel von Aicha – taps into Jewish mysticism, the zodiac, archangels and lesser angels, the four elements, the four wins, the four cardinal directions, and all manner of philosophical alchemy and hermeticism, esoteric philosophies and practices. With this guide you could become an alchemist and transmute ignorance into truth.

Writing in 1983, writer and physician Lewis Thomas (November 25, 1913–December 3, 1993) provides a lovely explainer as to what alchemy is:

Alchemy began long ago as an expression of the deepest and oldest of human wishes: to discover that the world makes sense. The working assumption — the everything on earth must be made up from a single, primal sort of matter — led to centuries of hard work aimed at isolating the original stuff and rearranging it to the alchemists’ liking. If it could be found, nothing would lie beyond human grasp. The transmutation of base metals to gold was only a modest part of the prospect. If you knew about the fundamental substance, you could do much more than make simple money: you could boil up a cure-all for every disease affecting humankind, you could rid the world of evil, and, while doing this, you could make a universal solvent capable of dissolving anything you might want to dissolve.

The work is akin to a grimoire, a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits, deities, and demons.

The University of Sydney explains:

Grimoires were very popular from 1600 AD thru 1900 AD. The Black Dragon, Red Dragon and the Black Screech Owl are all examples of grimoires or magical texts. The term “Grimoire” is a derivative of “grammar”. Grammar describes a fixed set of symbols and the means of their incorporation to properly produce well-formed, meaningful sentences and texts. Similarly, a Grimoire describes a set of magical symbols and how best to properly combine them in order to produce the desired effects. True grimoires contain elaborate rituals, many of which are echoed in modern Witchcraft rites. Sources for the information in the various Grimoires include Greek and Egyptian magical texts from 100-400 A.D. and Hebrew & Latin sources. Grimoires were used much more by sorcerers, wizards, and early church officials than by witches.

Buy Prints of All Three Charts in the Shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.