1953: Police officers guarding the entrance to 10 Rillington Place, scene of several murders, in Notting Hill, London, pose for a photograph. Photo by Charles Ley

At just before 9am at Pentonville Prison on 15th July 1953 and with his arms already pinioned behind his back, John Reginald Halliday Christie complained that he had an itchy nose. The hangman, Albert Pierrepoint, told him not to worry too much, ‘it won’t bother you for long,’ he said. From that point everything moved so quickly that Christie would have hardly known what was happening. Pierrepoint was particularly proud of the speed of his executions and they rarely took more than a few seconds after the condemned prisoner had set eyes on him. Pierrepoint had a macabre party piece which he demonstrated every time he got a new assistant executioner. Before leaving his room to hang anyone, he would sometimes light a cigar and then leave it burning in an ashtray. When he returned to the room after the hanging, he would draw on the cigar and show that it was still alight.

Execution notice of John-Christie on the gates of Pentonville Prison, July 1953

Albert Pierrepoint the offical executioner of England seen here on honeymoon with his wife . September 1952

Pierrepoint had been an executioner since September 1932 when after a week-long induction course at Pentonville prison, his name was added to the List of Assistant Executioners.. Pierrepoint’s first execution as ‘Number One’ was nine years later and of the ex-nightclub owner and gangster Antonio ‘Babe’ Mancini, at Pentonville on 17 October 1941. Just before the trapdoor was sprung Mancini was heard to utter a muffled ‘Cheerio!’ Mancini was to be the first of many and Albert Pierrepoint, who took pride in making death by hanging ‘as instant and humane a thing as it could ever be’, went on to hang 433 men and seventeen women during his lifetime.

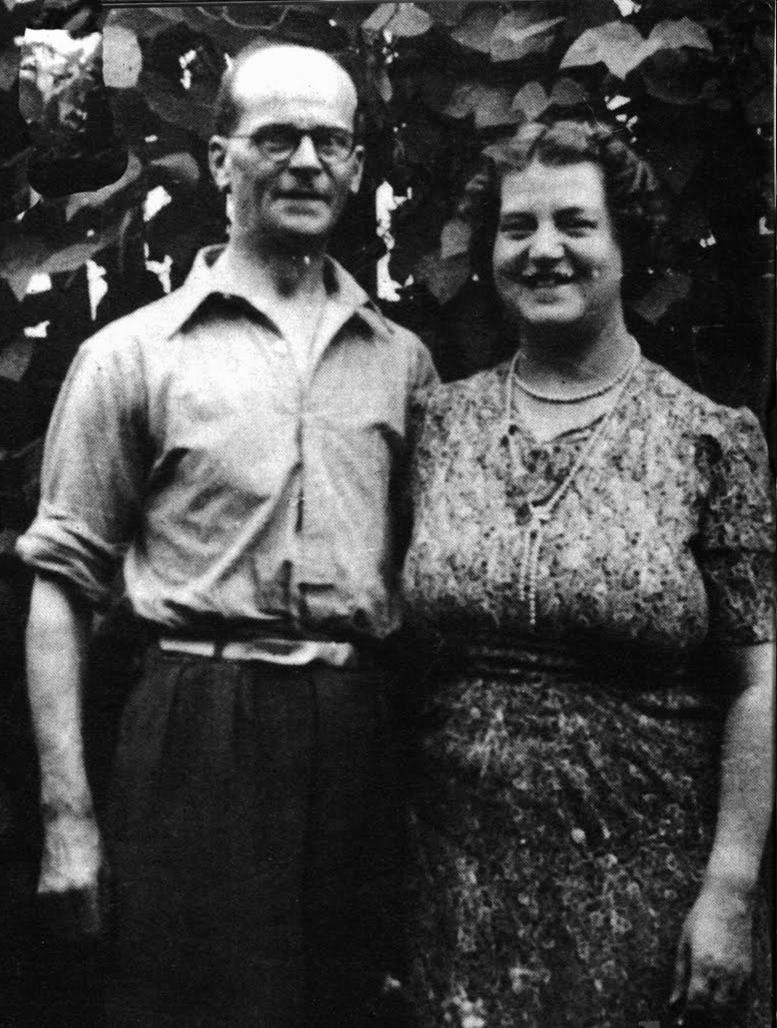

John Reginald Christie and his wife Ethel and who he would later murder

Few tears were ever shed for Christie but it hadn’t been a good year for supporters of capital punishment, although most of the population were. It could almost be seen as the beginning of the end for the death penalty in Britain. The last hanging would take place in 1964 before capital punishment was abolished for murder the following year in Great Britain and in 1973 in Northern Ireland.

Two weeks before Christie’s execution there had been a free vote in a crowded House of Commons. The Labour MP Sydney Silverman, diminutive in stature and with thick flaxen hair and matching eyebrows, had stood up in the chamber and under the ten minute rule introduced a Bill that, if made law, would suspend the death penalty for an experimental period of five years. It wasn’t the first time the MP for the Lancastrian seat of Nelson and Colne had proposed this. Silverman had also been the author of an amendment to the 1948 Criminal Justice Bill that had also wanted to suspend the death penalty for five years.

Sydney Silverman MP in 1954

At that time, during a Labour government, the amendment had passed with a majority of 23 – a majority that would have been greater if the Prime Minister Clement Atlee, with an eye on public opinion polls that consistently showed considerable support for keeping the gallows, hadn’t told his ministers not to vote for Silverman’s amendment. After the vote the Labour Home Secretary, 65 year old James Chuter Ede decided to reprieve all murderers from execution but only until the House of Lords had voted on the bill.

Six months later, and to nobody’s particular surprise, the upper house rejected Silverman’s amendment but on November 18th the Home Secretary announced that he would set up a Royal Commission on Capital Punishment. The Commission, however, was not to consider whether Capital Punishment should be abolished or not but only to discuss the manner of its application and whether liability for murder could or should be limited or modified. On the same day as the Royal Commission was announced the hangmen were sent back to work.

It was an emotive issue for many but especially for a man called Stanley Clark who had murdered his wife in Great Yarmouth and was the first to be hanged for over half a year. By the time the Commission initially convened in April 1949, it had been noted by more than a few that oddly the average murder rate was 50% higher during the six weeks following the end of the Home Secretary’s reprieve compared with the seven months the deferment had lasted. When Sydney Silverman, on that warm July evening in 1953, stood up to propose suspension of the death penalty for the second time, the Commission that was composed of ten men and two women, had had 63 meetings at 11 Carlton House Terrace in St James (the former home of William Gladstone and which now houses the British Academy), but had still yet to publish its report. Silverman, speaking for the allowed ten minutes, said that it was now an appropriate time to re-enact the defeated clause of five years before.

The commission’s last sitting to hear evidence, he explained, was nearly two years ago and anyway the question of abolishing or suspending the death penalty was expressly excluded from the commission’s terms of reference. Do not wait for the Commission’s report Silverman said, ‘It has nothing to do with this. It is for Parliament to decide. Let Parliament decide’. Silverman went on to add, ‘one of the things which has always influenced thinking on this matter is the finality of the death penalty, that if you made a mistake there is nothing you can do to recall your error. Many people who might otherwise have opposed the death penalty were influenced by the view that such a mistake was virtually impossible’.

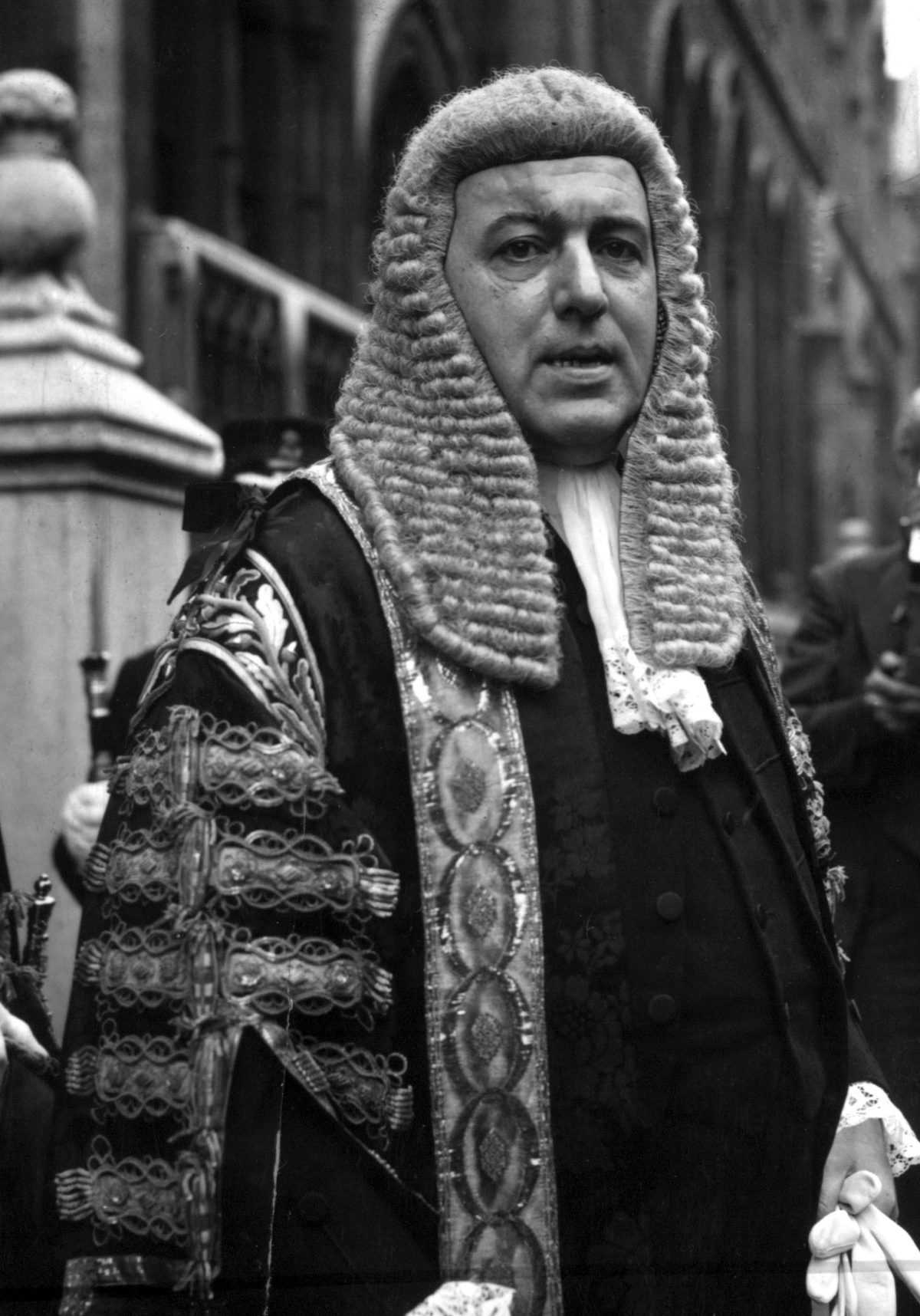

The Lord Chancellor, Viscount Kilmuir the former Home Secretary, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe leaving the courts after being sworn in as the new Lord Chancellor in London, 20/10/1954

The Labour MP then recalled that the present Conservative Home Secretary, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe had dealt with this point in 1948, not long after he had returned from being a prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials (he was, incidentally, instrumental in guiding the drafting of the European Convention of Human Rights), when he was asked whether there was any possibility that an innocent man might be put to death. Fyfe, who had at that point said:

There is no practicable possibility. Of course a jury might go wrong, the Court of Appeal might go wrong, as might the House of Lords, the Home Secretary. They might all be stricken mad and go wrong, but that is not a possibility which anyone can consider likely. You are moving in the realms of fantasy when you make that suggestion.

Silverman then put to the house:

I would like to know from the Home Secretary whether he still believes that. We have had this week the complete establishment that a case made against a man on the charge of murder succeeded, an appeal failed, an application for a reprieve failed, and that man was hanged. We know today that he was convicted and hanged on a false case.

At this point there were loud and long Conservative cries of ‘No!’ and ‘Shame!’ but after the interruptions had died down Silverman repeated the words ‘on a false case’ and said that ‘the House should agree to the motion on the ground that they had no right, until human judgement was infallible, to pass and execute an irrevocable doom. Inevitably, and with the Conservative Home Secretary, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe pointedly not present at the debate, the ‘˜ten-minute’ bill was thrown out by the House of Commons by 257 votes to 195 – a majority of 61. Even the Manchester Guardian the next morning wrote ‘Mr Silverman quite overreached himself, and it was no surprise that the Commons rejected his proposal’.

Beryl Evans and baby Geraldine

Terrified face of a doomed innocent- in one of the most infamous miscarriages of justice in British legal history, Timothy Evans was convicted of the murder of his wife and daughter, and in 1950 hanged.

Silverman had been referring to the 25 year old Welsh lorry driver called Timothy Evans who in 1950 had been convicted and hanged for the murder of his pregnant wife and fourteen month old daughter. The bodies of whom were found at 10 Rillington Place in Ladbroke Grove. Three years later in March 1953 the grisly remains of three women were found in a boarded up alcove in a kitchen in the very same house. The bodies, just a few weeks old, were later identified as Rita Nelson, Kathleen Maloney and Hectorina MacLennan – all prostitutes and described as ‘among the most forlorn of their company’.

The Daily Mail pruriently noted that one of the women had been pregnant and was wearing only a ‘pink silk slip’ but the newspaper also pointed out, and it wasn’t alone, that the sinister discoveries were particularly disturbing because the victims had all been strangled and disposed of not only in the same house but in roughly the same manner as Evans’s wife and child. In 1950, Timothy Evans’s original trial received relatively little publicity or controversy despite the horrific nature of the murders. The Manchester Guardian’s report on the jury’s guilty verdict was a tiny column tucked away on page 5 between the crossword and an advertisement for Sobranie cigarettes – ‘In the satisfying flavour of the new Sobranie American No. 50’s another wanderer has come to rest, beyond the reach of novelty’s temptation’. Evans, who according to Mr Justice Lewis, had ‘lied and lied and lied’ was hanged at Pentonville Prison by Albert Pierrepoint on 9th March 1950. A John “Reg” Christie had been the main prosecuting witness in Evans’s trial and had sat impassively at the back of the court when the guilty verdict was announced. The last words that Evans was purported to have said to both his mother and sister were: ‘Christie done it’.

When the three further bodies were found three years later the investigating detectives let it be known that they were satisfied that there was no connection between these bodies and the 1949 murders in the same house. After yet another body was found under some floorboards the following day the newspapers reported that the police were extremely eager to find John Christie who had suddenly left his ground floor rooms at Rillington Place the week before. Christie was not far away and had been staying at a guest house in King’s Cross but when the news of the bodies became public, one of which was soon identified as his wife, he started wandering around London sleeping rough and spending much of his time in cafes. Managing to evade capture for a few days Christie was eventually found and arrested by a policeman on 31st March 1953 staring into the Thames near Putney Bridge. All he had on his dishevelled person were a few coins, his identity card and an old newspaper cutting about Timothy Evans.

The back room at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, London, where John Christie hid one of his murder victims.

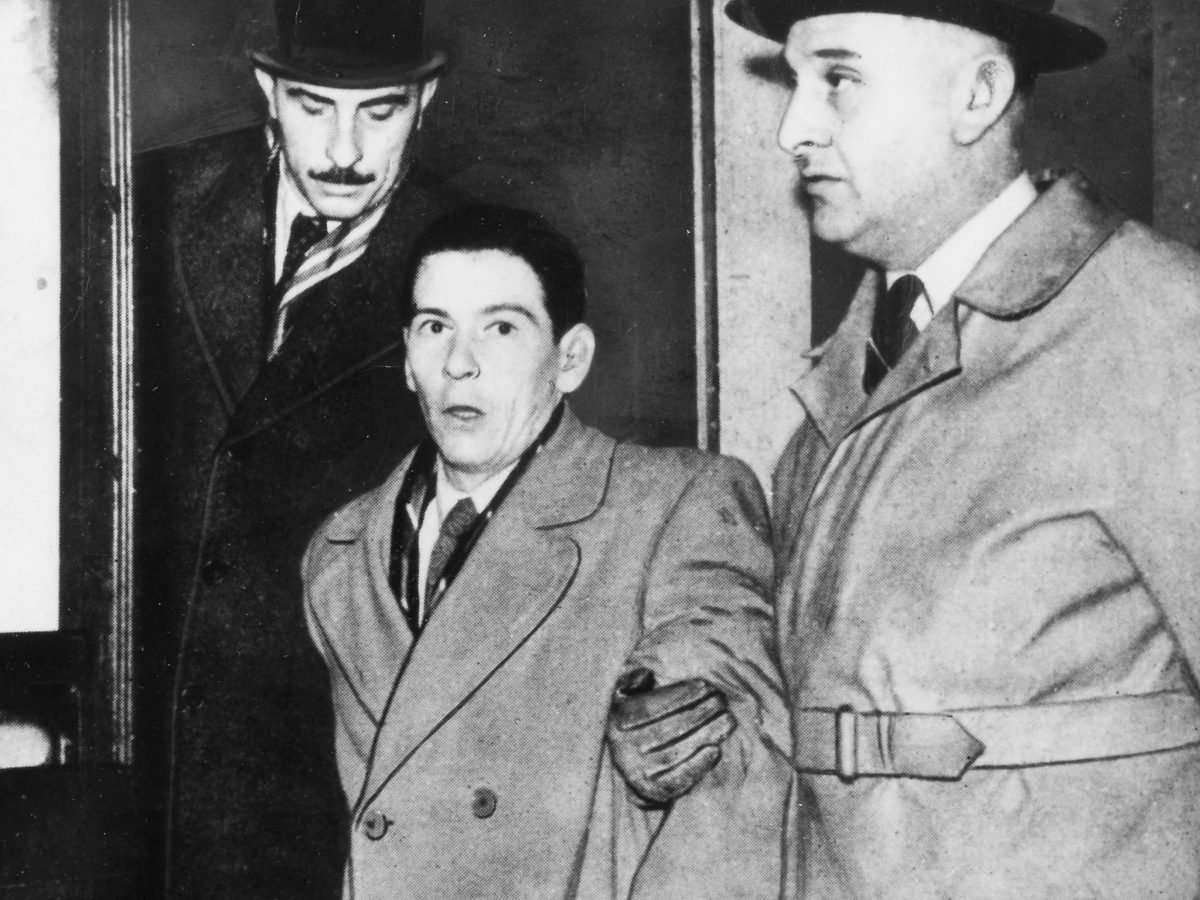

John Christie arriving at Magistrates Court 1953

Crowd outside Central Criminal Court for Christie trial

The back garden at 10 Rillington Place 1953

Maureen Riggs witness at Christie Trial

Christie leaving Brixton Prison for court

John Christie leaving court in a police van after the trial accusing him of his wife’s murder at 10 Rillington Place.

On June 22nd 1953 Christie’s trial began at the Central Criminal Court during which he admitted that he had killed his wife and six other women including Mrs Evans. Essentially he had murdered the women between 1943 and 1953, usually by strangling them after he had made them unconscious with domestic gas. He then raped them as they lay there, unconscious.

During the trial Mr Justice Finnemore, said: ‘it has been made quite plain by Inspector Griffin and Mr Curtis-Bennett that there is no suggestion that anybody other than Evans killed the child’. In his closing speech Sir Lionel Heald who had led the prosecution but was also the Attorney-General said ‘I think you [members of the jury] will understand how, especially in my position…in a governmental position — it is most important that nothing avoidable should be said in Court which might cast an unjustified reflection on the administration of justice..’. Christie’s defence of insanity failed and he was found guilty and sentenced to death.

Even if one former home secretary thought that a wrongful conviction for murder was infinitesimally small and the current Home Secretary thought it would be ‘in the realms of fantasy’ to even make the suggestion – there was a growing sense of unease that Timothy Evans may have been hanged for something he hadn’t done and this dented the public’s sense of infallibility of justice for murder. Maxwell-Fyfe, the home secretary commissioned an inquiry to investigate the possibility of a miscarriage of justice and chaired by John Scott Henderson QC. As is often the case, the Establishment thought that it was more important that the public were reassured that no mistake had been made, as far as Timothy Evans’ conviction was concerned, than any real search for truth in the matter. The inquiry lasted for just one week (it was decreed that the inquiry had to be completed before Christie’s execution) and its findings upheld Evans’ guilt in both murders. It explained Evans’ guilt for both Beryl’s and Geraldine’s murders with the explanation that Christie’s confession was unreliable because he wanted to help his defence that he was insane.

18th April 1953- Crowds of the curious gather to watch as the contents are cleared

Kathleen Maloney (left), one of the victims of British serial killer John Reginald Christie

Mrs Hart, the neighbour of serial killer John Reginald Christie, points to the spot in the garden of 10 Rillington Place, London, where two of his victims were buried, circa 1953

Children playing outside 10 Rillington Police in 1953

Henderson’s conclusion was met with much scepticism but twelve years later, in 1965, yet another inquiry was ordered by the current Labour Home Secretary, Sir Frank Soskice, this time chaired by the High Court judge Sir Daniel Brabin. Brabin, this time, found it was ‘more probably than not’ that Evans murdered his wife but that he did not murder his daughter. An odd conclusion considering both bodies were found together and murdered in the same manner. Since Evans had only originally been convicted of the murder of his daughter Roy Jenkins, the new Home Secretary, recommended a royal pardon for Evans, which was granted in October 1966. Evans’ body was exhumed from Pentonville Prison and he was reburied in St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Leytonstone, London.

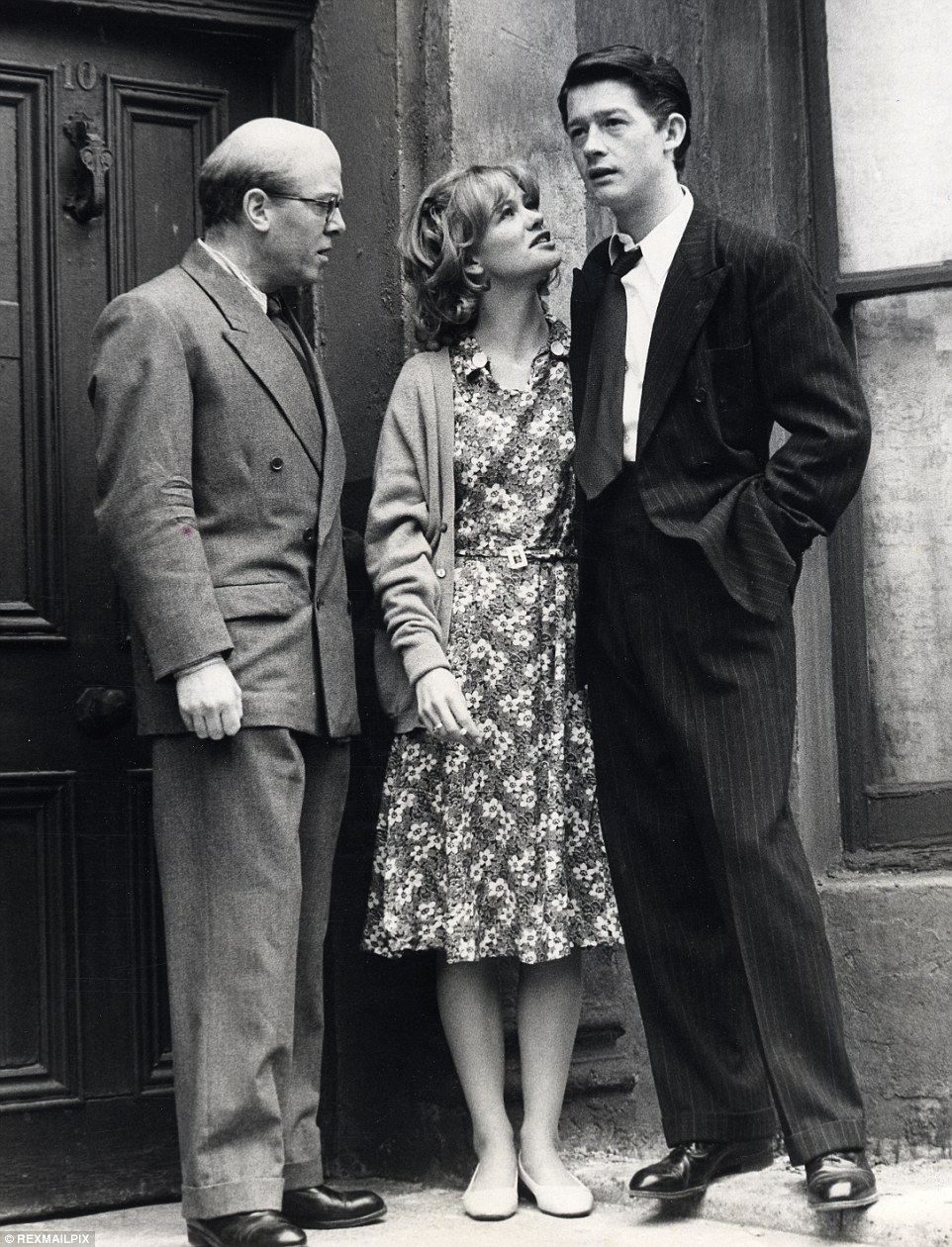

Rillington Place, renamed Ruston Close in 1954, was demolished late in 1970 as part of the general slum clearance in the area but not before it served as the location for the Richard Fleischer film 10 Rillington Place starring Richard Attenborough, Judy Geeson and John Hurt.

12th October 1966: Children playing outside 10 Rillington Place, London, the home of the mass murderer, John Christie. (Photo by Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images)

Richard Attenborough, Judy Geeson and John Hurt outside 10 Rillington Place, 1970

In January 2003 the Home Office awarded Timothy Evans’ half-sister, and his sister Eileen compensation for the miscarriage of justice in Evans’ trial. Lord Brennan QC wrote that the conviction and execution of Timothy Evans for the murder of his child was wrongful and a miscarriage of justice but he also added that there was no evidence to implicate Timothy Evans in the murder of his wife and that she was most probably murdered by Christie. The case of Timothy Evans was just one of several that contributed to the abolition of capital punishment for murder in 1965. It will aways remain, however, as one of the most appalling miscarriages of justice in the United Kingdom during the twentieth century.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.