The Reverend Harold Francis Davidson, Rector of the small Norfolk coastal village of Stiffkey for twenty-five years, was utterly besotted and bewitched by pretty young girls. Of that there is no doubt. How he behaved in the company of said pretty young girls was more up for debate; and in 1932 it seemed that the whole country, including the highest echelons of the Church of England, was debating exactly that.

Every Sunday, from 1906 to 1932, with a break for the First World War when he joined the Royal Navy, the Reverend Davidson was always at his pulpit at the Stiffkey church. He then spent the rest of the week, however, in London, usually Soho, catching the first train every Monday morning and the last one back to Norfolk on Saturday night. It was said that the only time he spent the entire week in his parish was during the General Strike of 1926. The Stiffkey locals joked that it was best not to die on a Monday morning as the body, especially in the summer, would be decomposing by the time the Reverend made it back for the funeral. Wedding services were either deputised or the ceremony was held on a Sunday. All the same, he was well liked by most of his parishioners.

During the week Davidson, often without his ‘dog collar’, would walk around the streets of the West End, essentially stalking and pursuing girls and young women wherever he went. Whether it was attractive young actresses, shop girls or waitresses, none of them was particularly safe from the glint in the Reverend’s eye. He always argued, until the day he died, that as he was wandering around Soho he was doing nothing but God’s work. His aim in life, he claimed, was helping young women from falling into a life of prostitution, particularly shop assistants and tea shop waitresses, many of whom had left an acrimonious home for the first time and were on very low wages.

Harold Davidson in the pulpit at Stiffkey

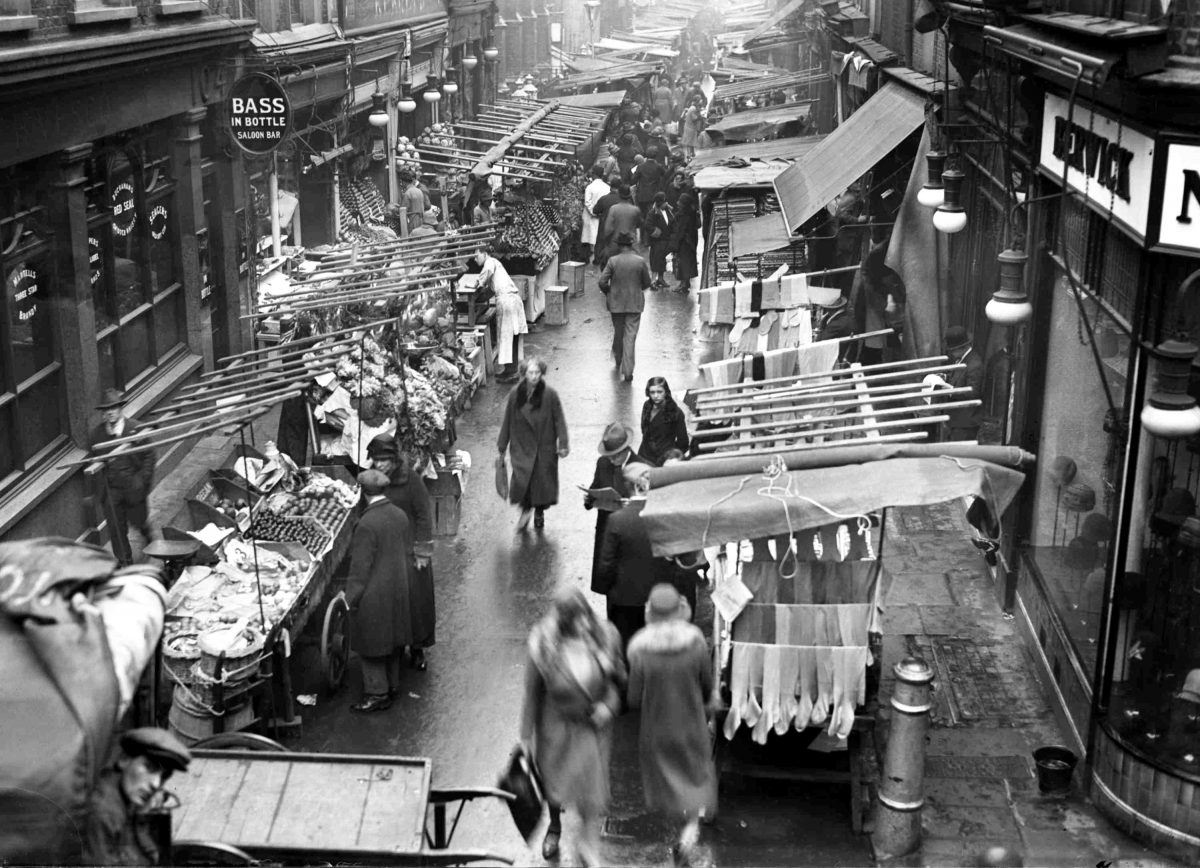

The famous Berwick Market in Soho, London, on Nov. 19, 1928

It had all started in 1894 when Davidson was working as a comic actor in London. He had come from a long line of clergymen (he would eventually be ordained in 1903 at the age of 28) but had always loved amateur dramatics at school, and subsequently toured for several months with friends, performing as travelling entertainers. One evening, walking along the Thames Embankment in a thick fog, he came across a 16-year-old young woman who was about to throw herself into the Thames. Davidson managed to stop her from her suicide attempt and found out that she had run away from home and had no money or anywhere to stay. He persuaded her to go back home with a letter from him to her mother: ‘Her pitiful story made a tremendous impression on me … I have ever since … kept my eyes open for opportunities to help that kind of girl.’ [1]

During the first part of the 20th Century and before the beginning of the First World War, however, most of Davidson’s early work was with underprivileged boys in the East End. He helped set up the Newsboys’ Club to help out young London newsboys who were often badly treated and exploited by Fleet Street. Clubs were created where the young boys could get a meal and play games and generally be kept out of mischief. Davidson, with others, helped the boys secure better wages and improve their working conditions. His work with young women, however, became more prominent after he returned home from war service as a naval chaplain, to an adulterous and pregnant wife.

At his own estimation, Davidson had made the acquaintance, in one way or another, of two to three thousand girls between 1919 and 1932: ‘I was picking up in this way roughly, as my diaries show, an average of about 150 to 200 girls a year, and taking them to restaurants for a meal and a talk, of these I was definitely able to help into good jobs of work a very large number.’ When the Reverend talked about ‘restaurants’ he almost certainly was referring to cafés such as the J. Lyons tea shops, of which there were many around London in the twenties and thirties. The waitresses in the Lyons tea shops at the time were called Nippies and it was a Nippy that was once involved in an incident with Harold Davidson. A friend of the Reverend, called J. Rowland Sales, remembered a time when they were having a cup of tea in the Coventry Street Corner House between Piccadilly and Leicester Square. Davidson had become visibly upset while telling a very sad story about a homeless couple he had recently found sleeping under a hedge in Norfolk. All of a sudden his demeanour changed. It was almost like he was a completely different person, recounted Sales. A young ‘nippy waitress’ had just walked by and Davidson leapt to his feet and called out ‘Excuse me, Miss. You must be the sister of Jessie Matthews‘. He then promised the startled waitress that he would get her a part in a new play that was opening in London.

Miss B Lillywhite, a ‘nippy’ at Coventry Street Corner House in Piccadilly is ready to take an order from a customer

Davidson, with the Bishop of Norwich’s full support, had become the chaplain to the actor’s Church Union and he started using this as an excuse to appear backstage at various West End theatres. He became known as a ‘voyeuristic pest’ and would often open doors backstage: ‘Oh, excuse me ladies, I didn’t know this was your dressing room…’ Tales like these and other bizarre stories of the Reverend Davidson’s behaviour around Soho eventually came to the notice of his employer – the Church of England. A complaint was made, via a handwritten letter, to the Bishop of Norwich, the Right Reverend Bertram Pollock, by a 17-year-old young woman called Barbara Harris. In 1931 the Bishop decided to investigate Davidson, and soon the self-styled ‘Prostitutes’ Padre’ was charged with five offences against public morality under the 1892 Clergy Discipline Act. He was to be tried in a Consistory court, an ecclesiastical court used by the Church of England to this day for the trial of clergy (below the rank of bishop), and it opened in the Great Hall of Church House in Westminster on 29 March 1932. A Consistory court has no jury and is presided over, in place of a judge, by what is called a Chancellor of the Diocese. In Davidson’s case it was before F. Keppel North the Chancellor of the Diocese of Norfolk. It was never revealed at the time, and certainly should have been, but not only had Bishop Pollock and Chancellor North been to the same university together, but Mr North was the Godfather to the Bishop’s daughter.

Star prosecution witness Gwendoline Harris (known as Barbara Harris) arrives at the church disciplinary trial of Harold Davidson (1875 – 1937), Rector of Stiffkey in Norfolk, at Church House, Westminster, London, 30th March 1932. Davidson was charged with immoral conduct in connection with his work with prostitutes and the case resulted in Davidson being defrocked later that year. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Harold Davidson talks to his solicitors outside Church House Westminster, 31st March 1932, during a case brought against him after scandalous allegations regarding his work with prostitutes. The case resulted in Davidson being defrocked later that year. (Photo by J. Gaiger/Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The court case was a sensation and front-page news. Davidson wasn’t slow in courting the press, and on the first day of the trial arrived in flamboyant style while smoking a characteristically large cigar. He even signed autographs. Amongst what seemed like dozens of Nippies, theatre girls, and domestic servants brought up to give evidence, the prosecution’s star witness was a young woman called Barbara Harris whom Davidson had befriended in 1930. He had first seen her at Marble Arch – a popular haunt of prostitutes at the time – and he used his old tried and tested trick of comparing Barbara to a famous actress, this time Greta Garbo. Barbara was just sixteen and already a prostitute and suffering from gonorrhoea. She had never known her father and had been abandoned by her mother who was suffering from mental illness. Harris initially welcomed what seemed a kind gentleman’s offer of help and was soon pouring out her life-story to Davidson, no doubt in a Lyons cafe in the near vicinity. Davidson helped her find lodgings and they became friends over the next eighteen months.

The Rector had given Barbara money and even found her a job in domestic service at Villiers Street in Charing Cross, but she quickly tired of both the job and the reverend’s repeated attentions. At one point she gave him a black eye and threw coins at him but he continually came back for more. One morning, at 9 am, Davidson had appeared at the room where she was sleeping. During the court case the prosecution asked Barbara about this:

Prosecution: You say you kissed him?

Barbara: Yes.

Prosecution: How often was he kissing you?

Barbara: He was always kissing me.

Prosecution: Did he ever ask you to do things?

Barbara: Yes, he once asked me to give myself to him body and soul …

Family and friends of Harold Davidson (1875 – 1937), Rector of Stiffkey in Norfolk, at Davidson’s church disciplinary trial at Church House, Westminster, London, 30th March 1932. Davidson was charged with immoral conduct in connection with his work with prostitutes and the case resulted in Davidson being defrocked later that year. Left to right: Davidson’s son Newton Davidson, his sister Mrs Cox, his daughter Patricia and friend Lorraine Brown.

Rosie Ellis, one of the witnesses in the church disciplinary trial of Harold Davidson (1875 – 1937), Rector of Stiffkey in Norfolk, on her way to a court hearing at Church House, Westminster, London, 29th March 1932. Davidson was charged with immoral conduct in connection with his work with prostitutes and the case resulted in Davidson being defrocked later that year.

Sylvia Harris, sister of star prosecution witness Barbara Harris, arrives at the church disciplinary trial of Harold Davidson (1875 – 1937), Rector of Stiffkey in Norfolk, at Church House, Westminster, London, 31st March 1932. Davidson was charged with immoral conduct in connection with his work with prostitutes and the case resulted in Davidson being defrocked later that year.

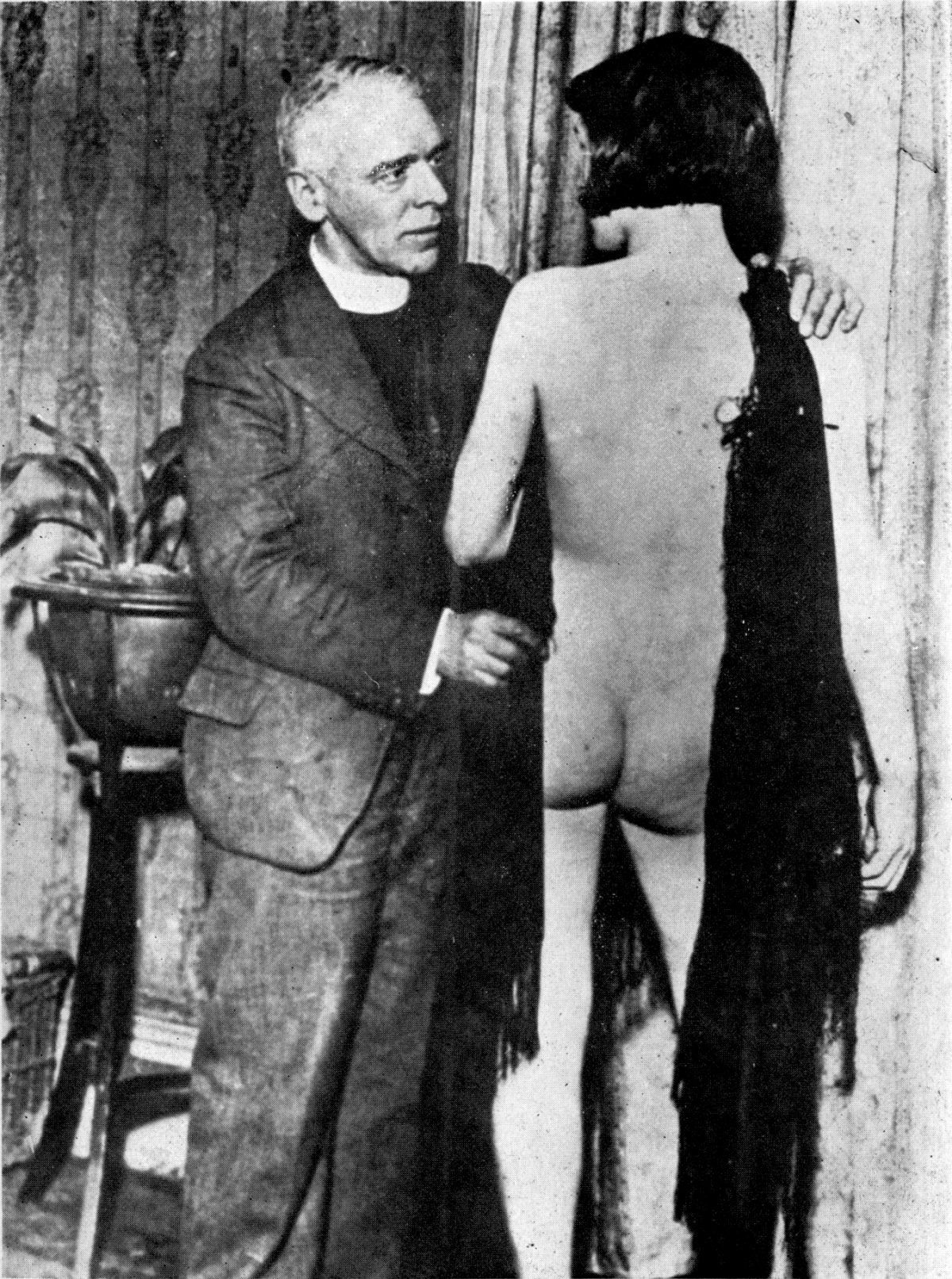

As the trial was coming to its end it was thought that the evidence against Davidson would not be enough to find him guilty. That is until the prosecutor, Roland Oliver, brought out two small photographs. To Davidson’s utter shock and horrified disbelief, one of the photographs was of the reverend standing between an aspidistra plant and a bare-bottomed teenage actress. The girl was called Estelle Douglas and was the daughter of a close friend of his – an actress called Mae Douglas, whom he had helped to get on stage some twenty years before. In turn she had asked Davidson to try and get her daughter into films. A photoshoot had been organised at the Stiffkey rectory with the idea of taking publicity shots of Estelle in her bathing suit. At one point the photographer told Estelle that the strap of the bathing suit and her chemise were both showing and, apparently out of earshot of the Reverend, asked her to remove them, leaving her with a black tasselled shawl to protect her modesty. A series of photographs were then taken. According to Davidson, the photographer offered fifty pounds to take a photograph of him and Estelle with the intention of selling it to the newspapers. Davidson was completely broke and needed the money and so he rather stupidly agreed to the request. Whether the photograph was set-up or not (there is much evidence to suggest that it was), it was the end for the ‘Prostitute’s Padre’ and Chancellor North found him guilty of five counts of immoral conduct. He was charged £8,205 costs and was left in financial and professional ruin.

Harold Davidson and Estelle

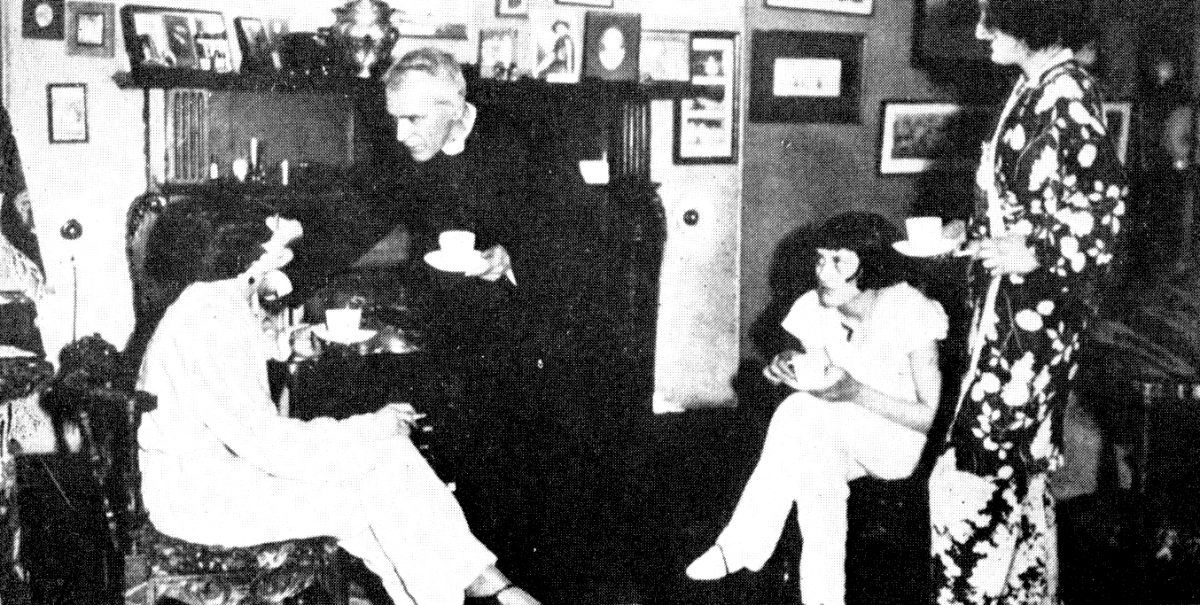

The Rectory Pyjama Party with Estelle on the right

Davidson’s legal team were let down by the eccentric Rector’s antics. He performed a tap dance at one point in the witness box, and for some reason always refused to question the truthfulness or character of any of the prosecution witnesses, including Barbara Harris. The defence were also at fault for Davidson’s conviction however. Letters between Harold Davidson had been produced in court as evidence – most of the letters from Davidson were signed ‘Your sincere friend and Padre,’ while the relatively mundane letters from Harris were either thanking Davidson for his help or confirming an appointment with him – but Harris’s original letter of complaint to the Bishop of Norwich was written in a completely different handwriting style. It was almost certainly written by someone else. Crucially this wasn’t noticed by the defence team. Another major mistake occurred when they failed to call Molly Davidson, the Reverend’s wife, as a witness. She had always been completely aware of Davidson’s charity work with young girls and, generally, had always supported him. She even often hosted ‘sleepovers’ with the girls at the rectory in Stiffkey.

In October 1932 Davidson was summoned to appear in front of Bishop Pollock at Norwich cathedral where he was subjected to a humiliating and demeaning public defrocking. ‘Removed, Deposed and Degraded’ shouted a Daily Mirror headline. At one point the Bishop knelt in prayer and after a reference to ‘Our sentence duly passed,’ declared the office of rector of Stiffkey and Morston to be vacant. ‘It appears to us,’ he said, ‘that the Rev. Harold Francis Davidson has been found guilty in our Consistory Court of certain immoral conduct, immoral acts, and immoral habits…we do hereby remove, depose and degrade him.’

While the Bishop and his procession reformed to leave the High Altar, the loud high-pitched voice of Davidson was heard again protesting his innocence. The Bishop completely ignored him and Davidson was left pleading his case in an increasingly hysterical voice as the clerical procession swept past him on their way out.

Harold Davidson was not alone in criticising his prosecutors and the fairness of his trial. While most of the national press saw him as little more than a joke figure, the Church Times, no less, was more on the ex-Rector’s side. While they criticised Davidson’s conduct as ‘foolish and eccentric’, they wrote in July 1932, that: ‘There can be no doubt that he was originally moved by a high Christian impulse, and that he is still regarded by many as a champion of the outcast and the wretched. However necessary the proceedings may have been, the spirit in which they were conducted has shocked the public conscience. The secret inquiry agents, the characters of some of the unnecessary witnesses, above all, the photograph, made the trial both undignified and unChristian.’ The article also mentioned that under the Clergy Discipline Act of 1892 a clergyman could be found guilty from one single immoral act and that ‘It was therefore perfectly superfluous to bring forward numerous witnesses of doubtful character and to heap up a number of charges.’

ETTWMR Reverend Harold Francis Davidson, the Rector of Stiffkey in Norfolk, a Church of England priest who, after a notorious court case in 1932, was convicted on charges of immorality and defrocked by the Church. Here the Reverend conducts an open air service after finding the church locked against him. 11th July 1932.

The Reverend Davidson wasn’t the first member of the establishment who spent much of their time helping fallen women in central London. William Ewart Gladstone was often found wandering around the darker environs of the West End. With almost reckless abandon he searched for young women to ‘rescue’, often asking them back to his house. A shocked Private Secretary once asked him ‘What would your wife say? ‘Why’ Gladstone answered, ‘it is to my wife that I’m bringing her’. His wife Catherine would indeed feed the women and give them a place to sleep before finding, not always entirely gratefully, a temporary shelter to stay. Although Gladstone was completely open about the ‘rescuing’ of the young street women and he even wrote in his diary that he occasionally committed ‘adultery of the heart’ and ‘delectation morosa’ (enjoying thinking of evil without the intention of action). It was estimated that Gladstone spent a minimum of £2000 a year helping prostitutes and providing shelters for them.

A fellow parliamentarian called Henry Labouchere, MP for Northampton, noted that Gladstone seemed to prefer the young and pretty prostitutes and wryly noted that he: ‘manages to combine his missionary meddling with a keen appreciation of a pretty face. He has never been known to rescue any of our East End whores, nor for that matter is it easy to contemplate his rescuing any ugly woman and I am quite sure his convention of the Magdalen is of incomparable example of pulchritude with a superb figure and carriage.’ Similarly, Ronald Blythe in his book The Age of Illusion, published in 1964, wrote in one chapter of the Stiffkey clerical scandal: ‘The Reverend Mr Davidson’s downfall … was girls. Not a girl, not five or six girls even, not a hundred, but the entire tremulous universe of girlhood. Shingled heads, clear cheeky eyes, nifty legs, warm, blunt-fingered workaday hands, small firm breasts and, most importantly, good strong healthy teeth, besotted him.’

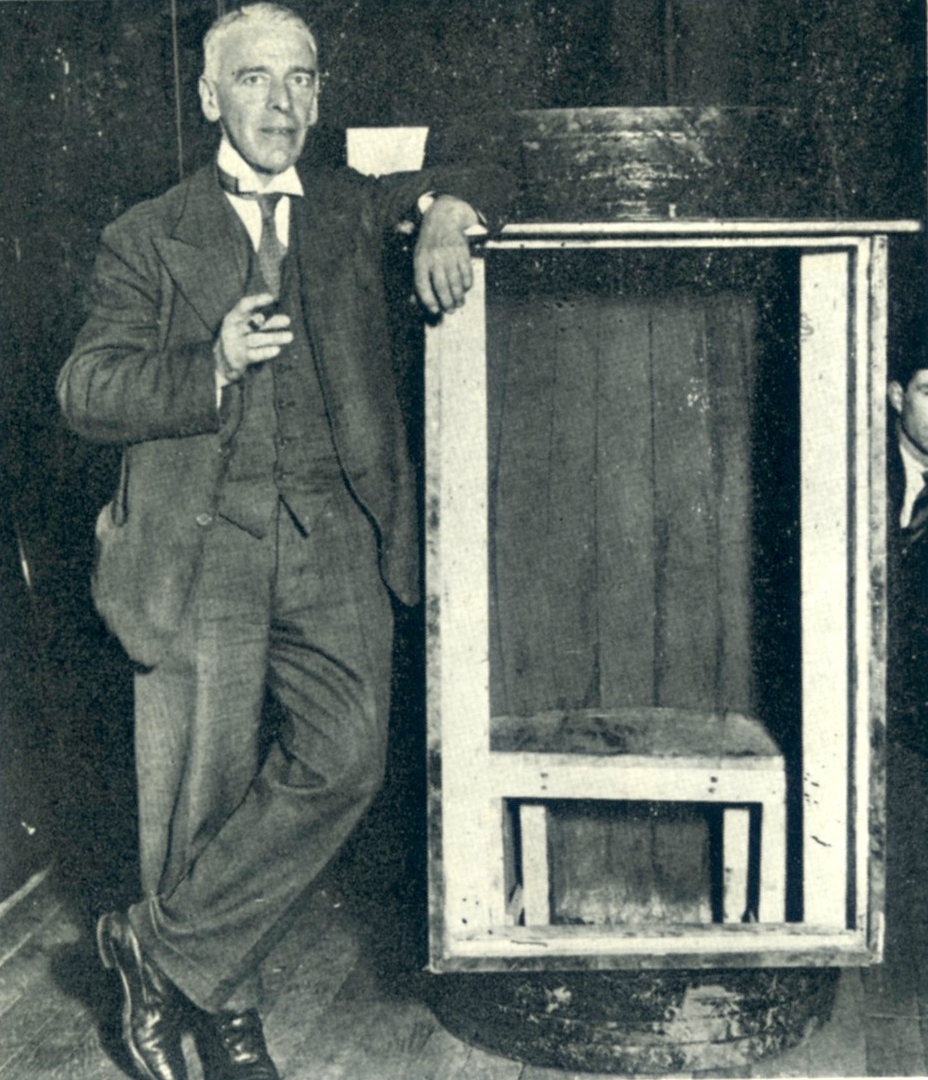

Davidson with barrel

After the public humiliation at Norwich Cathedral, Harold Davidson picked himself up and started to use his experience on the stage as a young man. He turned himself into a travelling showman in order to attract as much publicity for his case as possible. He also desperately needed money. He wanted to appeal his court case and believed he should have been tried by a jury. One infamous stunt involved him fasting inside a barrel at Blackpool. The container was fitted with an electric light and also a small chimney from which his cigar smoke could escape. Through a grille he’d protest his innocence to anyone who would listen and even invited Gandhi to meet him there for tea. To no avail … .

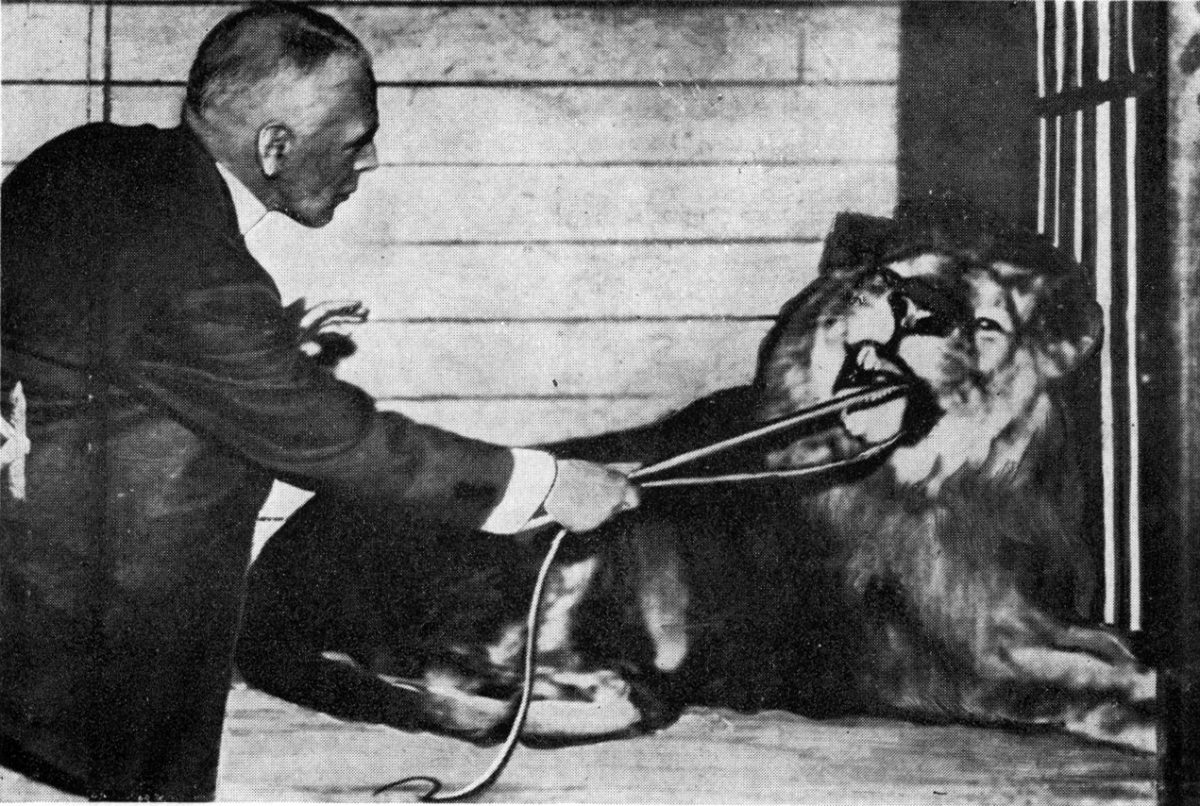

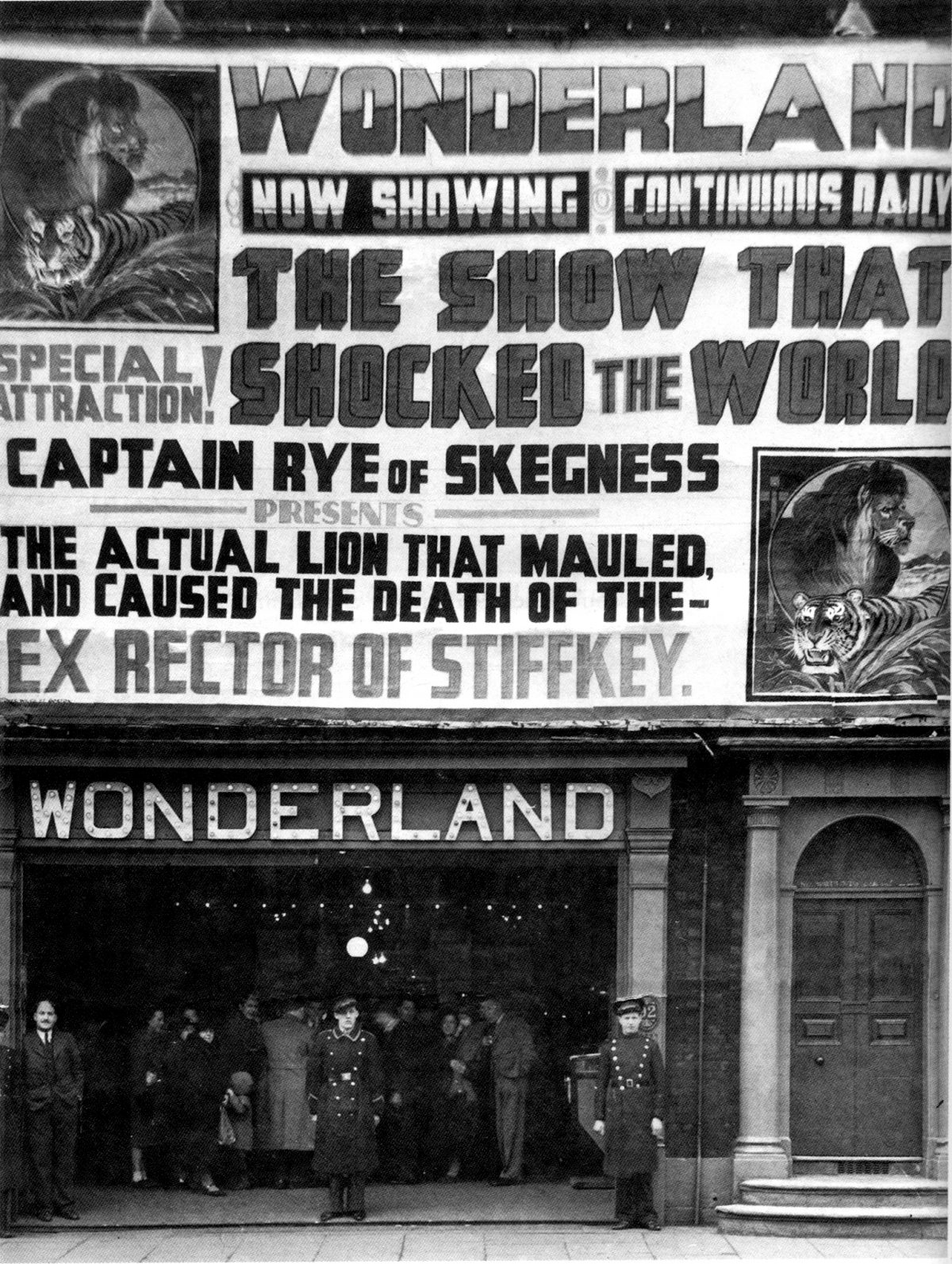

Despite his stunts becoming more and more outrageous – at one point he was being roasted in an oven while being prodded in the buttocks with a pitchfork by a mechanical devil – the erstwhile clergyman’s fame was beginning to wane. In the summer of 1937 Davidson tried one more stunt and at Thompson’s Amusement Park in Skegness he was billed as ‘A modern Daniel in a lion’s den.’ Davidson stood in a cage with a lion called Freddie and a lioness called Toto. Again he shouted to any passer-by about the injustice he had been dealt. This was merged, as usual, with a torrent of loud abuse against his former church leaders.

Harold Davidson with Toto the lion

On the 28th July, Davidson accidentally stood on Toto’s tail. The lioness’s sudden movement made Freddie attack the former rector. The Daily Mirror described the attack: ‘In a flash the angry beast had torn open both the ex-rector’s shoulders with its claws, and though Davidson bravely tried to strike with his stick he crashed to the floor of the cage with the lion on top of him. It gripped him by the back with its jaws and began to maul him, while spectators screamed in horror.’ [5] At this point it was the turn of a sixteen-year-old girl to attempt to save Davidson. A young assistant lion-tamer called Renée Somer picked up a whip and an iron cage and leapt into the cage. After raining blows on the lion with the whip and when it lurched towards her on the attack she rammed the iron bar into its jaws and then dragged Davidson across the cage out of immediate danger. Davidson was taken to Skegness Cottage Hospital fatally injured. It is said that the ex-Reverend, always hungry for publicity to help his cause and with blood pouring from his neck, still had the presence of mind to say: ‘Telephone the London newspapers – we still have time to make the first editions!’

The owner of the amusement park, with rather indecent haste, put up a notice that said ‘See the lion that mauled and injured the rector’. The next day he was asked to take the notice down, and then soon after the badly injured Davidson died of his horrific wounds. A verdict of misadventure was returned at the inquest. Davidson was buried in Stiffkey churchyard and with the help of the police to control the crowds, over two thousand mourners attended the funeral. His epitaph reads: ‘He was loved by the villagers, who recognised his humanity and forgave him his transgressions. May he rest in peace.

Harold Davidson’s Grave at Stiffkey

This is an excerpt from Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker.

Beautiful Idiots and Brilliant Lunatics by Rob Baker and published by Amberley Publishing.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.