In 1974, after a rough few years, Jean Seberg was asked in an interview how she was coping, “I’m feeling around,” she said, “if you want to know what I’ll be doing ten years from now. I couldn’t say. It’s like asking a woman whether she’ll be graceful at 45…

Six years later, aged 40, she was found in the back of a car on a side street in Paris. It was August and her decomposing body, wrapped in a blanket, had lain there undiscovered for ten days. The cause of death was an overdose of barbiturates and was deemed by the French authorities as “probably suicide”. A note to her son was found:

Forgive me. I can no longer live with my nerves. Understand me. I know that you can and you know that I love you. Be strong. Your loving mother, Jean.

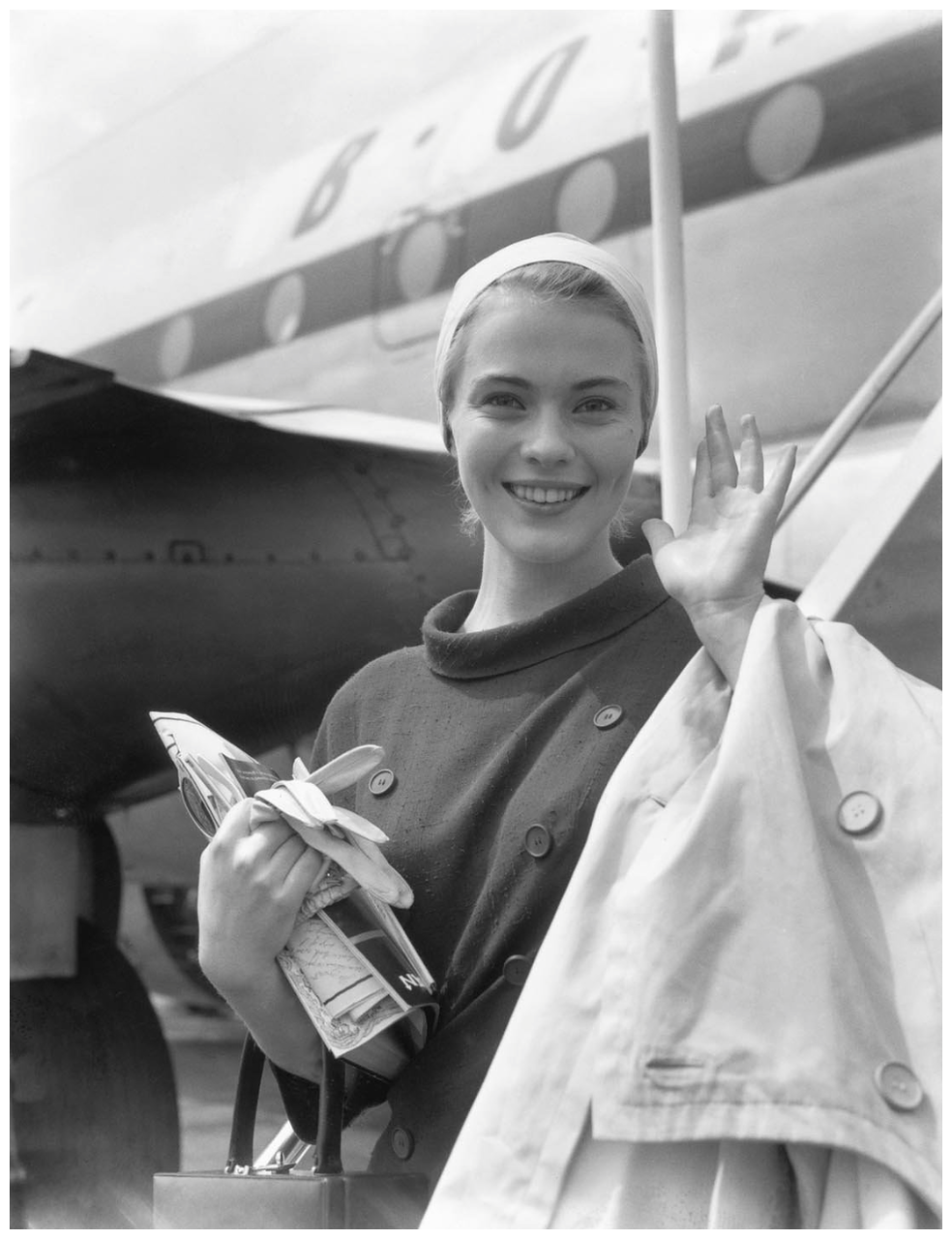

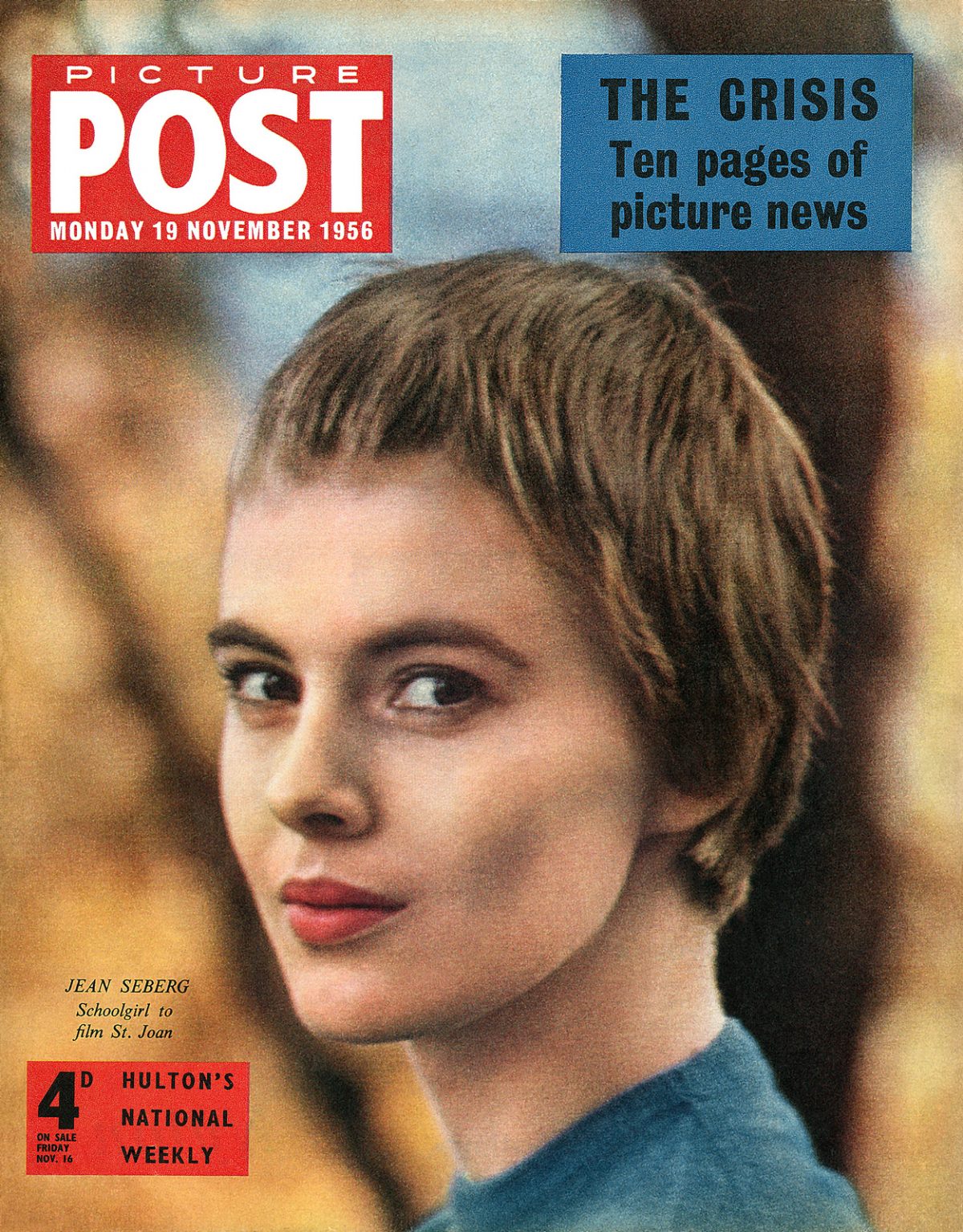

She was only just eighteen when she flew to England in 1956 to play the leading role in the movie version of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan. As an utterly inexperienced student from Marshalltown, Iowa, she had been chosen from 18,000 hopefuls by director Otto Preminger in a $150,000 talent search. The script was rewritten by Graham Greene and she had to appear along side John Gielgud, Anton Wallbrook and Richard Widmark. It must have been incredibly daunting.

The film was a flop both critically and commercially and while it was flawed in many ways most of the critics seemed to single out the teenage Seberg in particular. The Times wrote: ‘Joan was young, certainly, and ignorant, but she had outstanding qualities…and of those qualities Miss Seberg shows not a trace.’ ” The New Yorker’s John McCarten wrote of the movie, ‘The leading romper is a seventeen-year-old girl, who, as played by Jean Seberg, makes one long to give her a solid, and possibly therapeutic, paddling …’

Preminger was attacked for his presumption, Seberg said, “for trying to make an actress out of a country bumpkin like myself, and I was told (by the critics) to get back to the farm. It was amazing, the cruelty of some of the reviews.”

Jean Seberg arriving in London

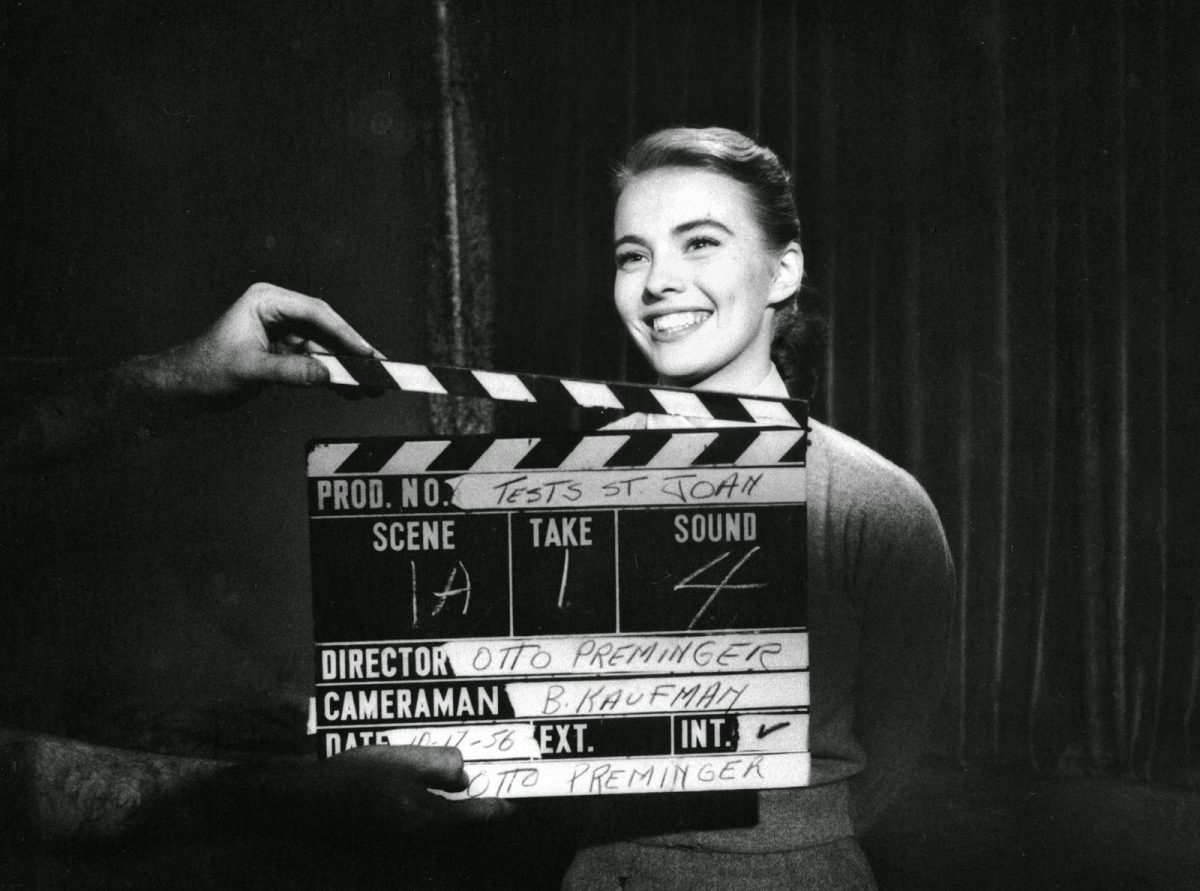

Jean Seberg, before the famous haircut, at her screen test for “Saint Joan,” 1956 by Bob Willoughby

Jean Seberg, before the famous haircut, at her screen test for “Saint Joan,” 1956 by Bob Willoughby

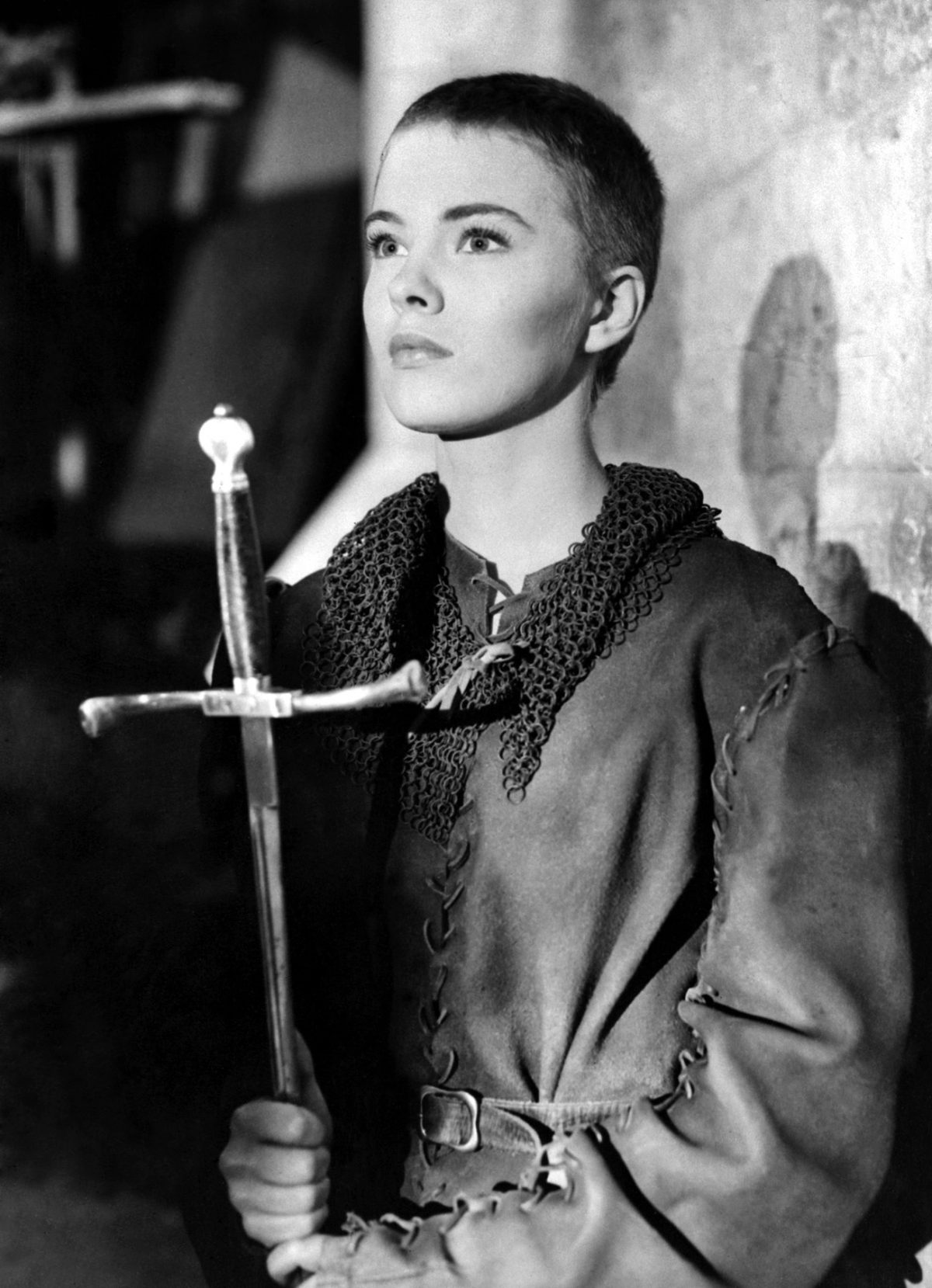

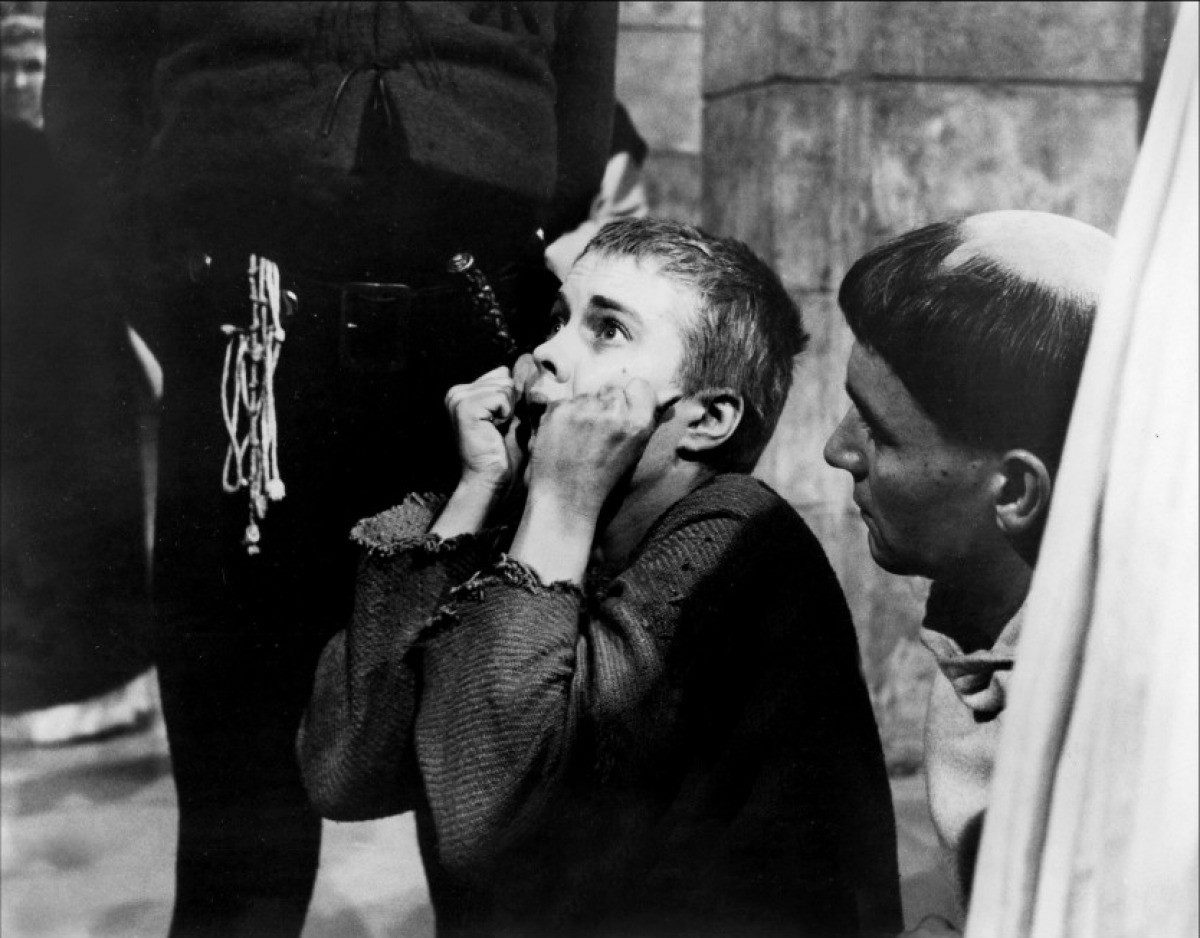

Jean Seberg on the set of Saint Joan, 1957

Saint Joan, 1957

Saint Joan, 1957

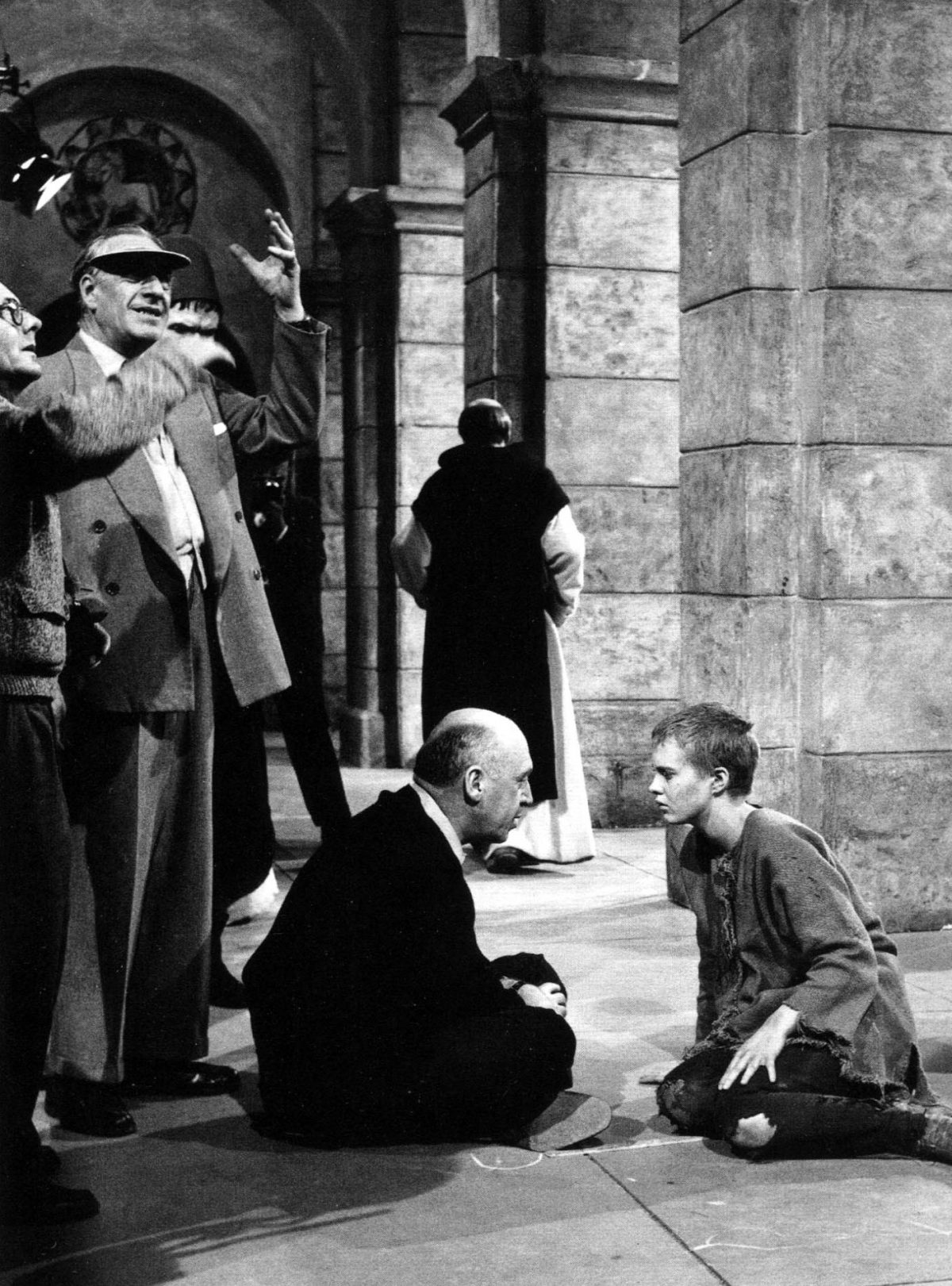

Director Otto Preminger and Jean Seberg on the set of Saint Joan, 1957

Quick interview with Otto Preminger but features an extract of Seberg’s first audition with him, 1956.

Seberg’s next film, also with Preminger, was Bonjour Tristesse, from the novel originally published in 1954 and written by the eighteen year old Francoise Sagan and co-starred David Niven and Deborah Kerr. Unfortunately it fared little better than her first and she later said: “There is one thing that I shall never forgive [Preminger] for: he took away from me the one thing that is most essential to an actress, and that is her self-confidence.”

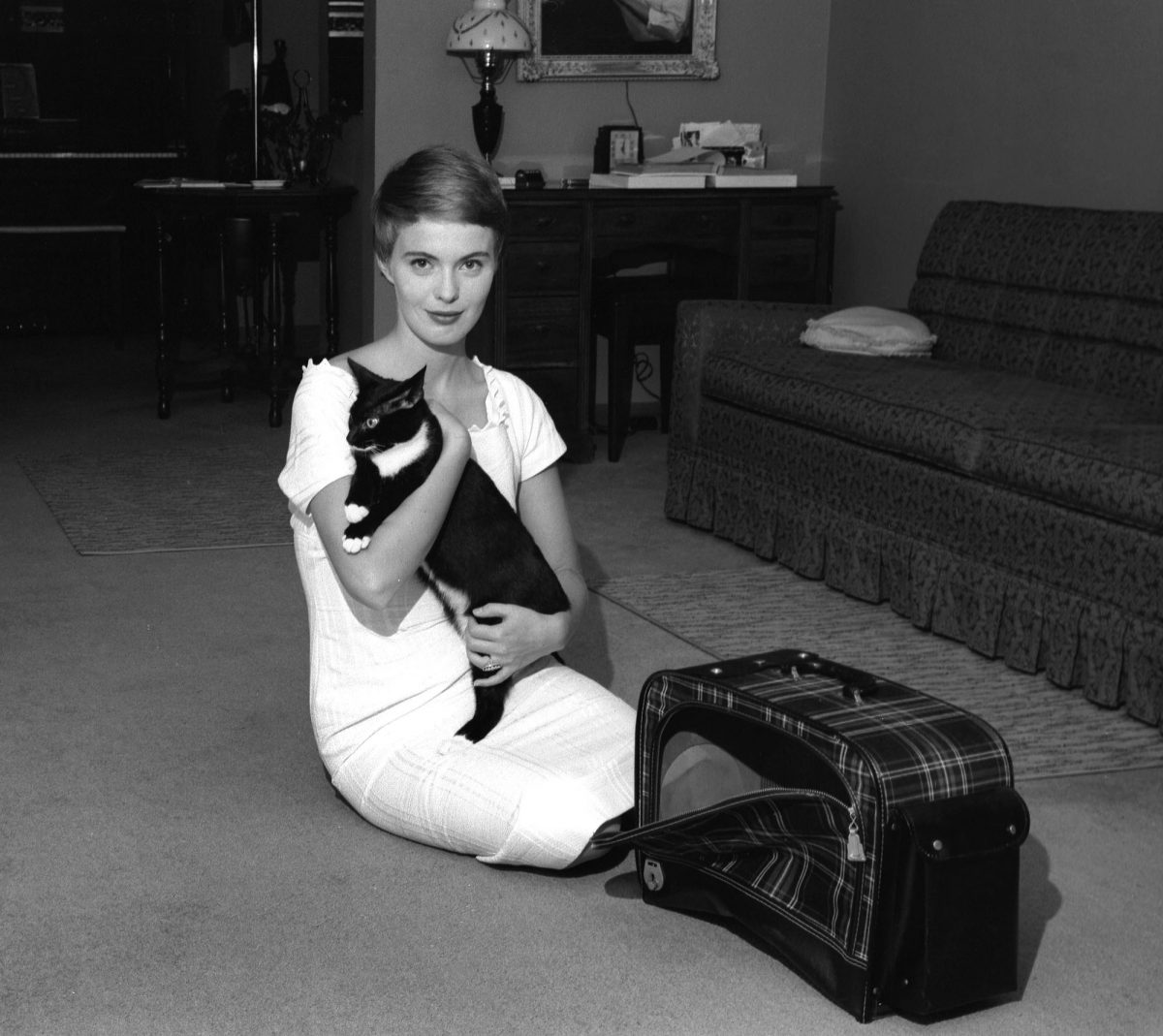

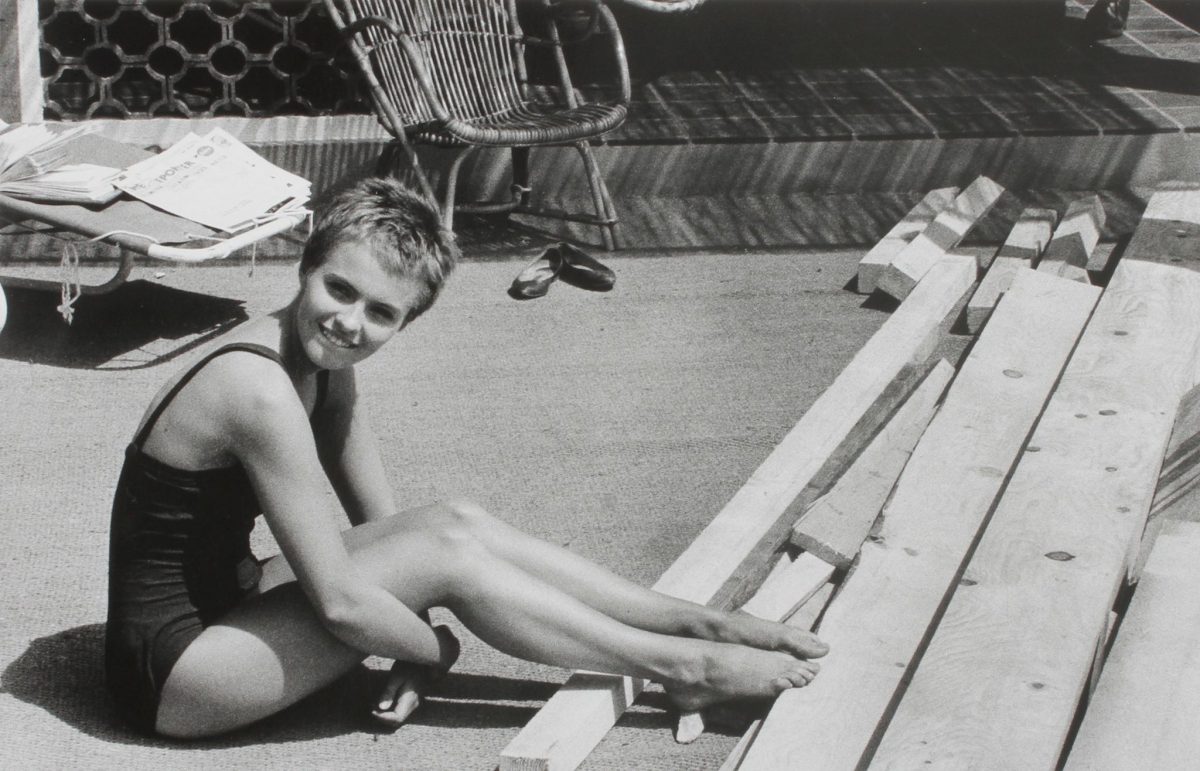

Jean Seberg in Marshalltown soon after filming Bonjour Tristesse in 1958 – photo courtesy of Jim Hamann

Jean Seberg – Aug. 1958 – photo courtesy of Jim Hamann

Jean Seberg – Aug. 1958 – photo courtesy of Jim Hamann

Jean Seberg – Aug. 1958 – photo courtesy of Jim Hamann

Jean Seberg – Aug. 1958 – photo courtesy of Jim Hamann

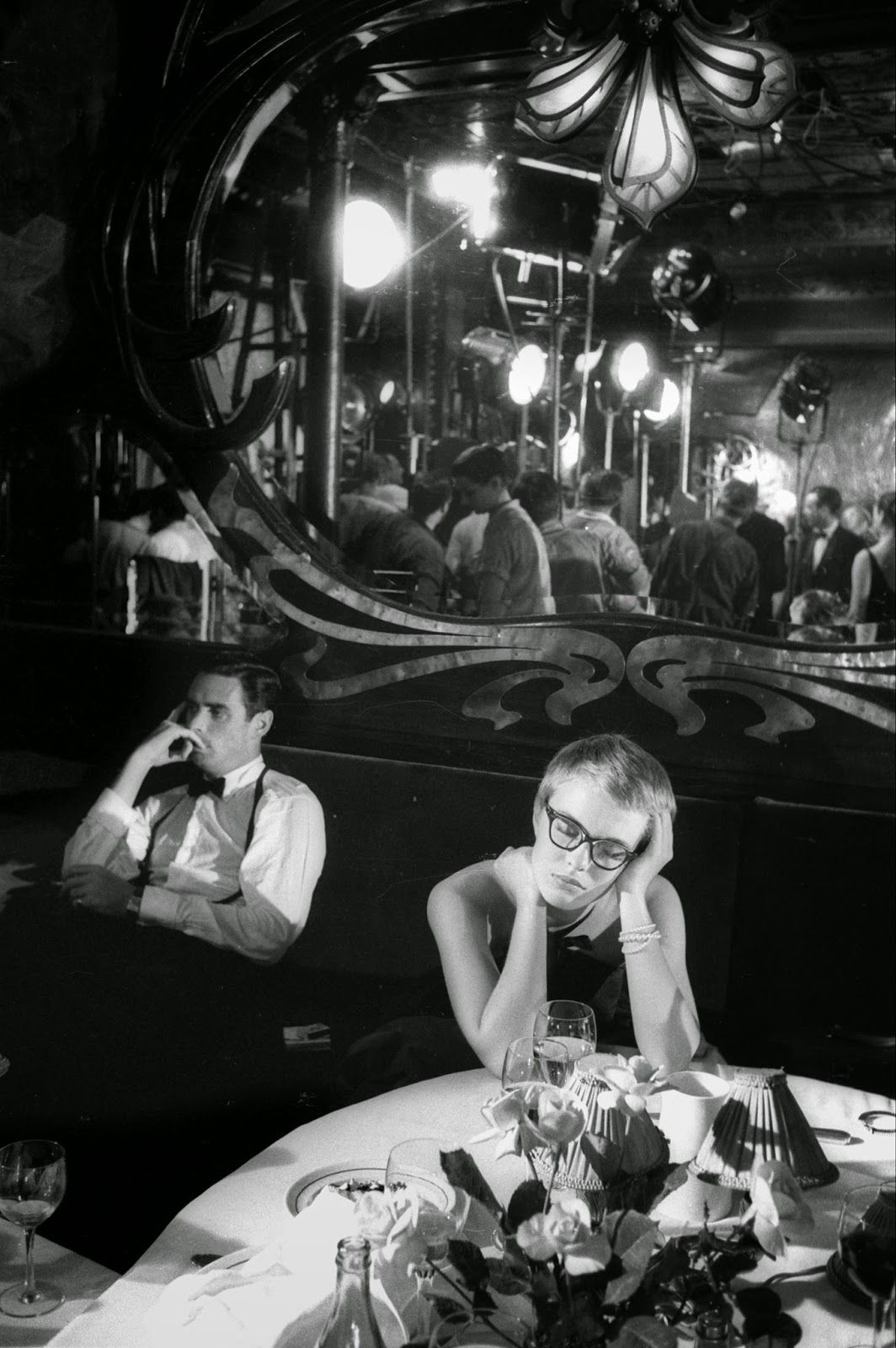

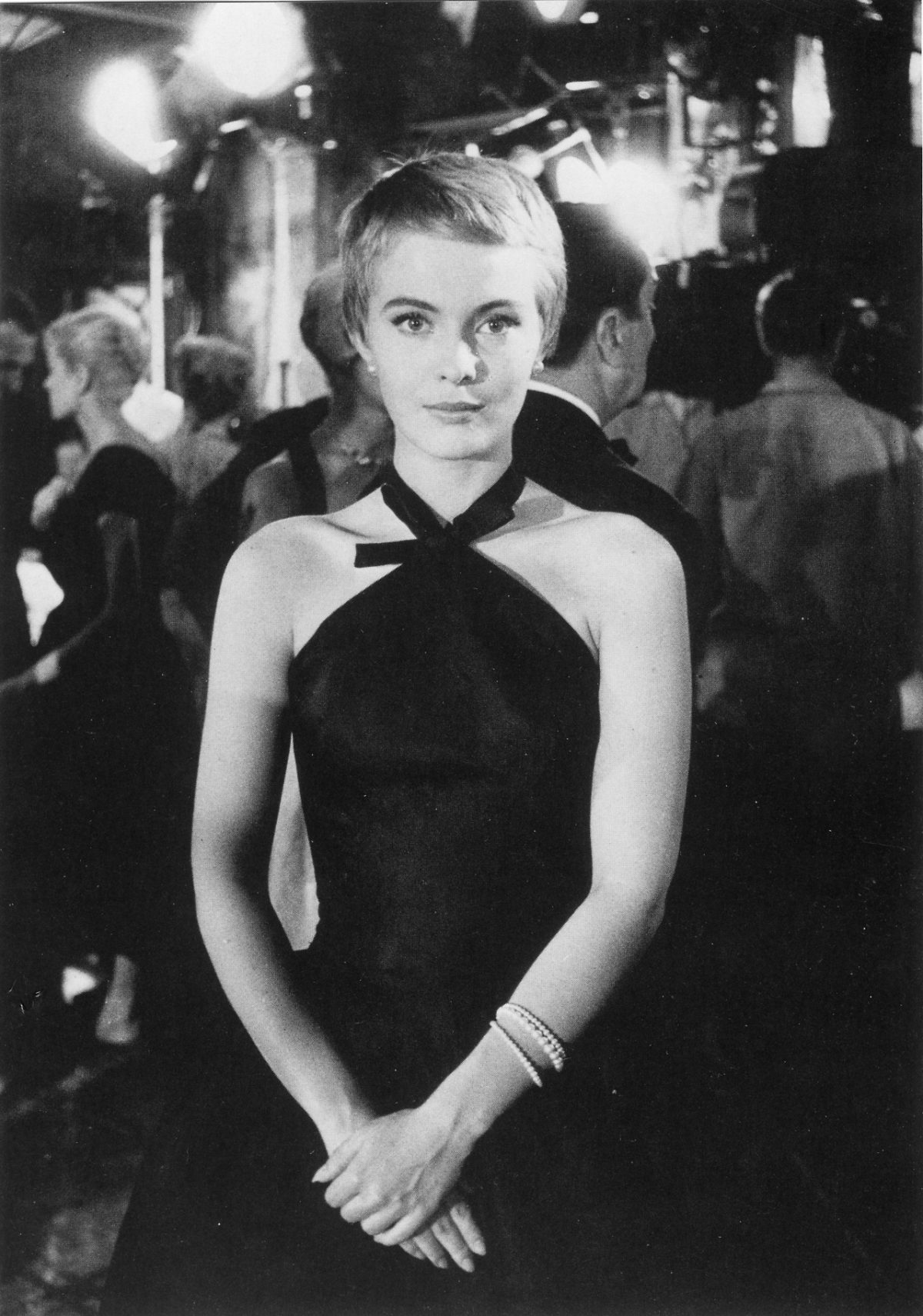

Jean Seberg during filming of Bonjour Tristesse at Maxim’s restaurant in Paris. Photo by Bob Willoughby

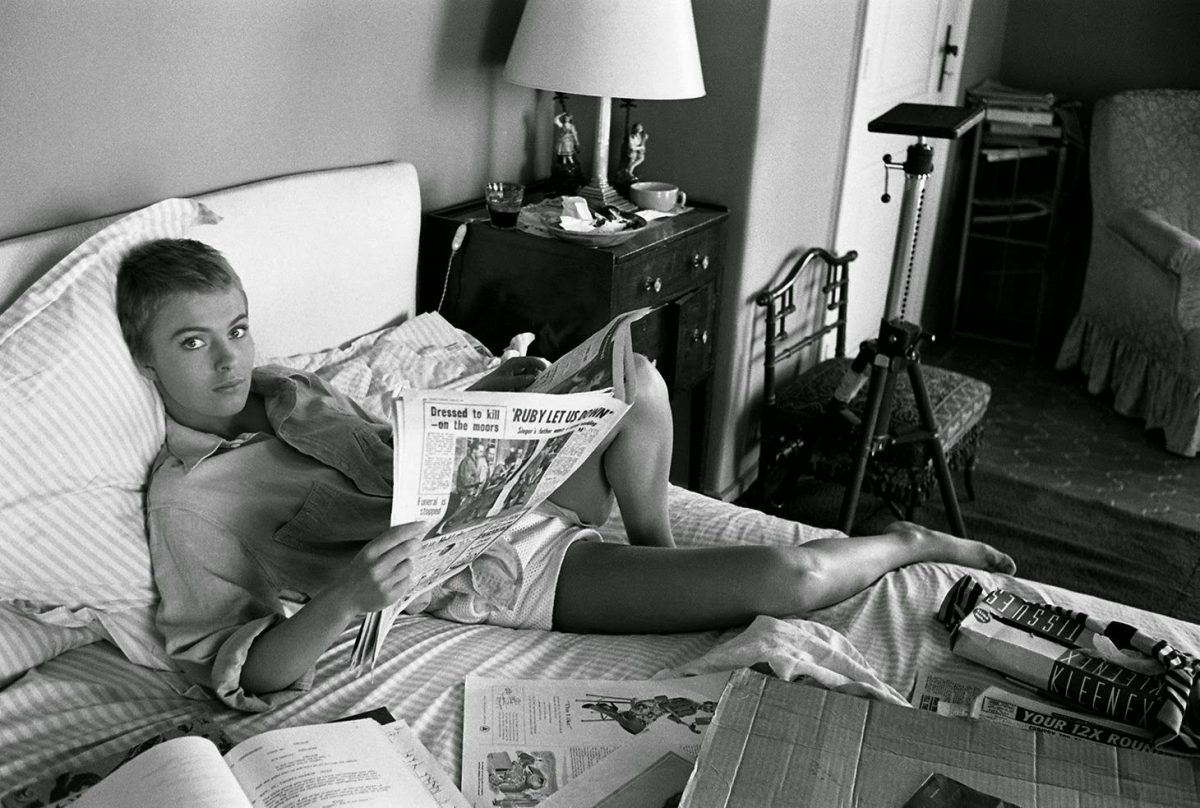

Jean Seberg reads the paper in bed during filming of Bonjour Tristesse in France

Jean Seberg from Bonjour Tristesse

Bonjour Tristesse

Jean Seberg The Mouse that Roared, 1959

Jean Seberg and François Moreuil, 1958.

While making Bonjour Tristesse on the French Riviera Seberg met and soon got engaged to a young lawyer called François Moreuil. She would later say that she became attracted to him because he seemed sophisticated and knew how to choose the right wine. They married on September 5 1958 in Seberg’s hometown of Marshalltown. Moreuil helped Seberg free herself from the contract with Preminger and her next film, distributed by Columbia, was The Mouse That Roared with Peter Sellers which became his international breakthrough. Around this time Moreuil heard that Jean-Luc Godard was planning to make a film, based on a treatment by Truffaut, about a small-time gangster and his girlfriend. The French new wave directors loved Preminger and Godard would later say, “The character played by Jean Seberg was a continuation of her role in Bonjour Tristesse. I could have taken the last shot of Preminger’s film and started after dissolving to a title: “Three years later”.

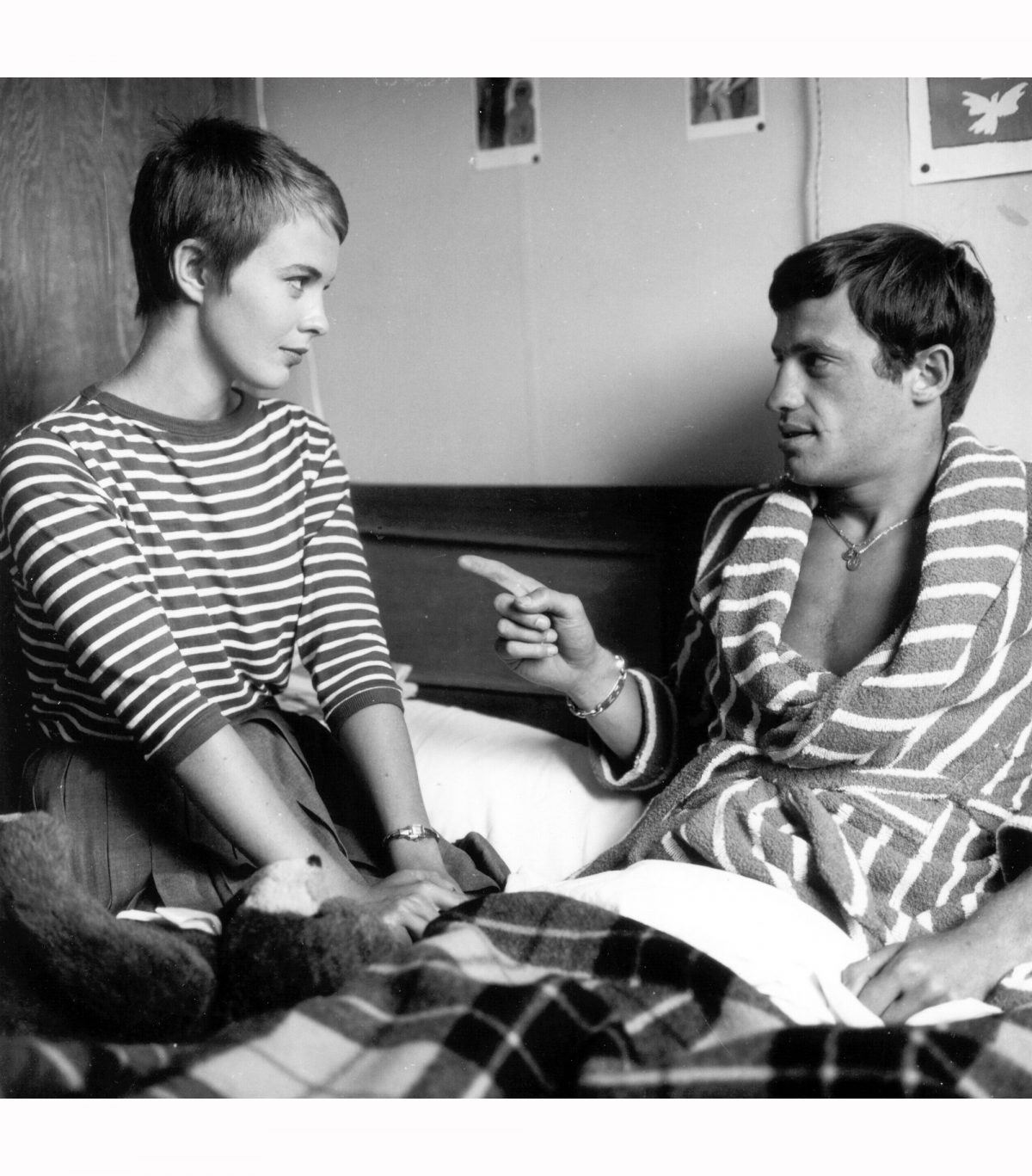

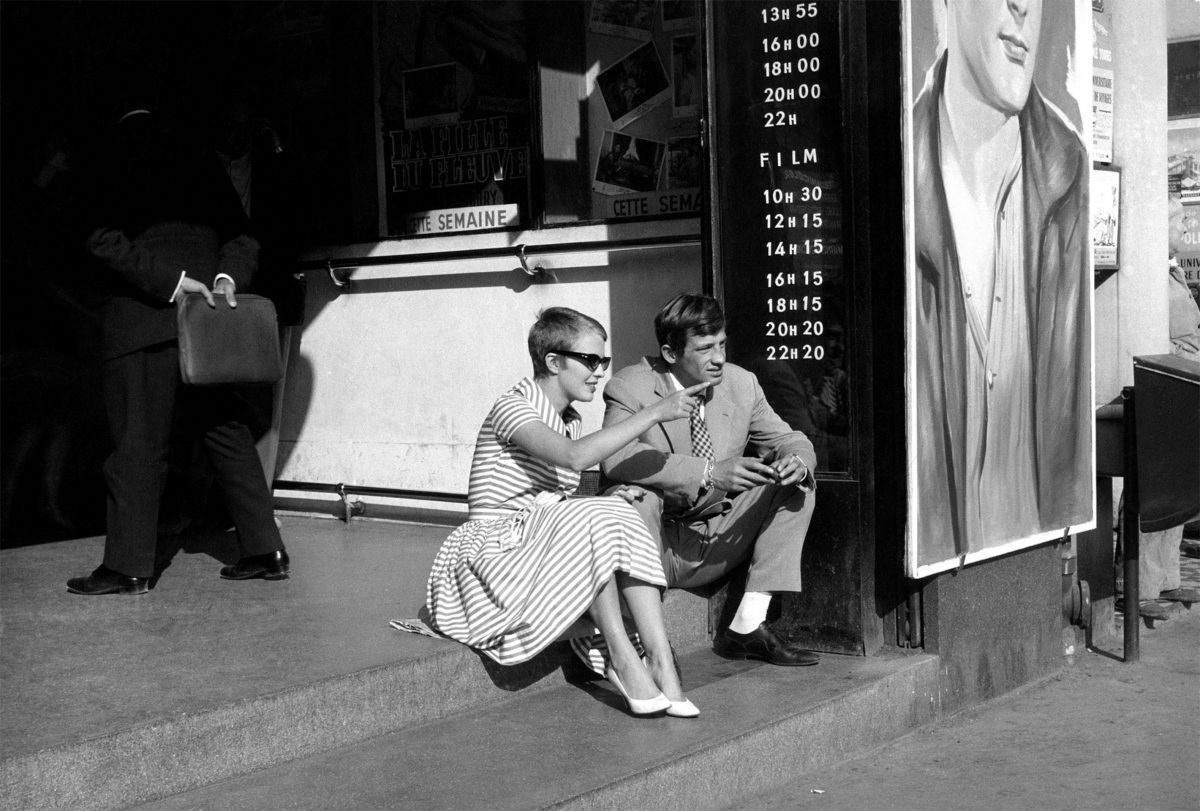

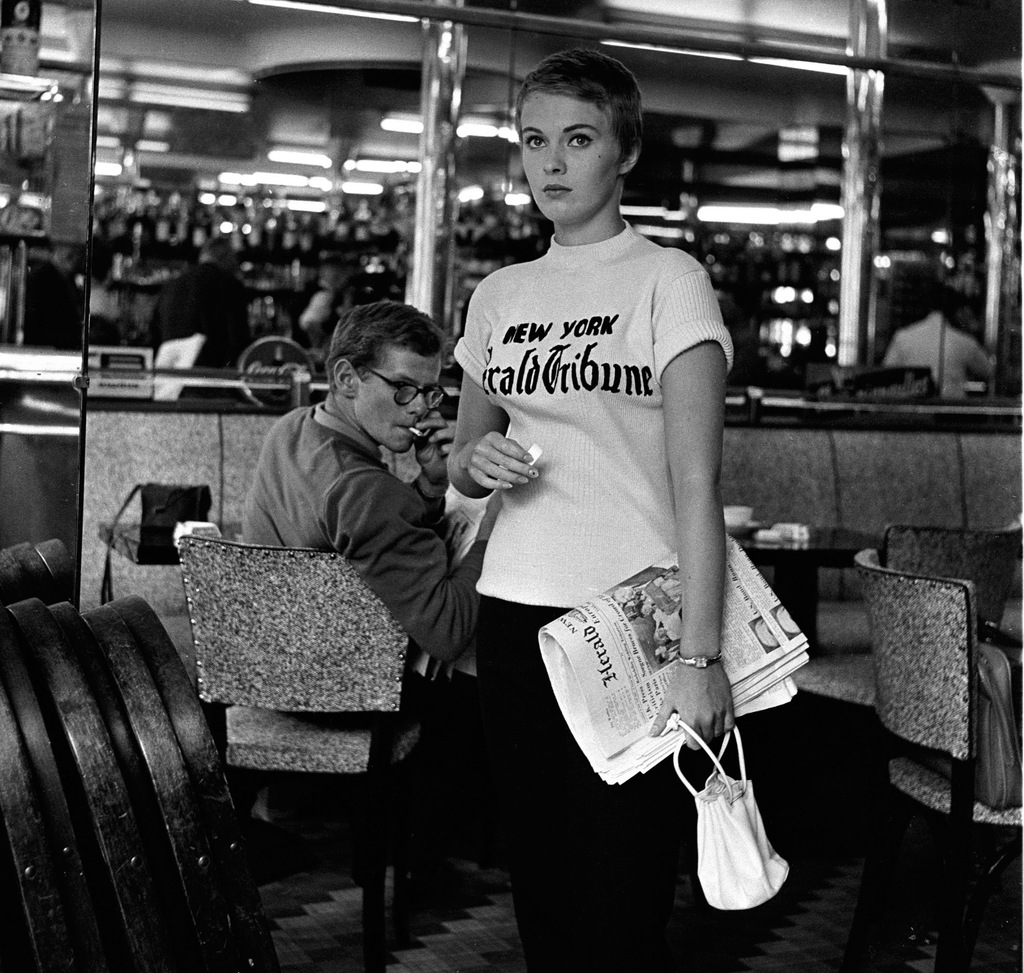

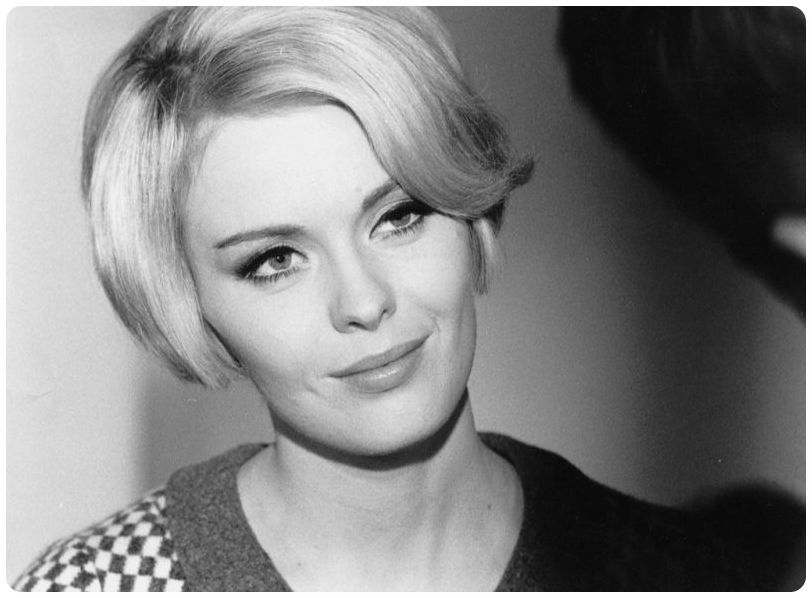

A Bout de Souffle, or Breathless as it became known in the English speaking world, at last brought Seberg acceptance by the critics. Not only that but her look and style with her pixie haircut, black eyeliner and the sailor stripes were copied everywhere. And still are.

Jean Seberg and Jean Paul Belmondo in Breathless

Jean Seberg and Jean Paul Belmondo

Raymond Cauchetier, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg in A bout de Souffle directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1960

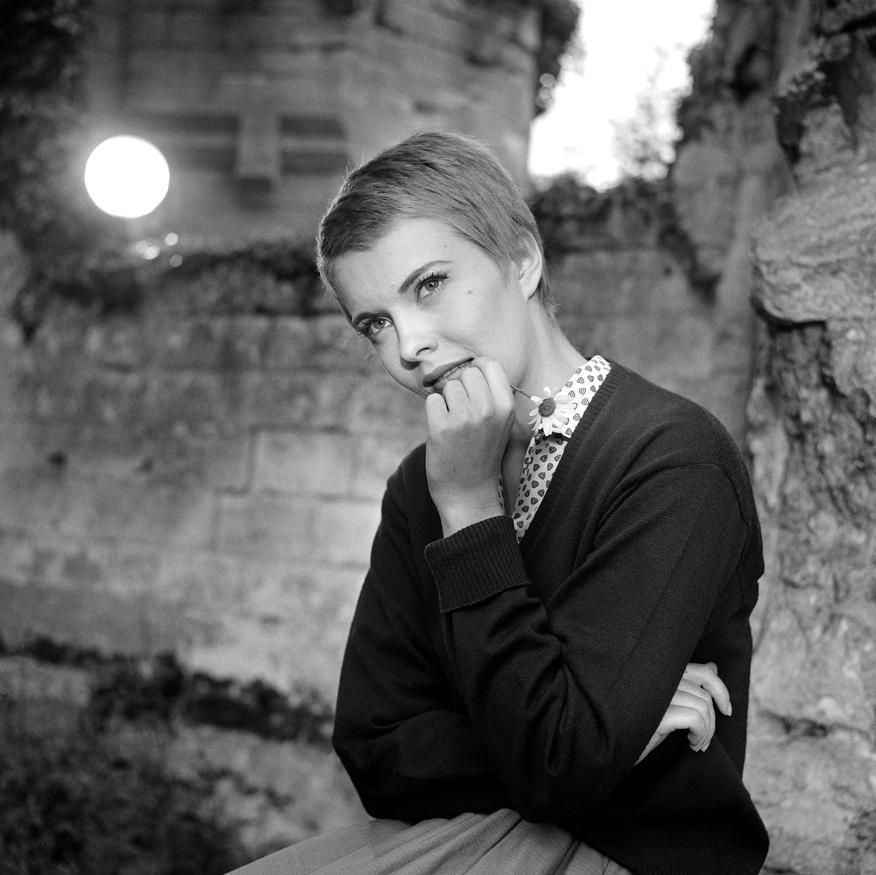

Raymond Cauchetier, Jean Seberg on the set of A bout de Souffle directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1960

Raymond Cauchetier, Jean Seberg in A bout de Souffle directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1960

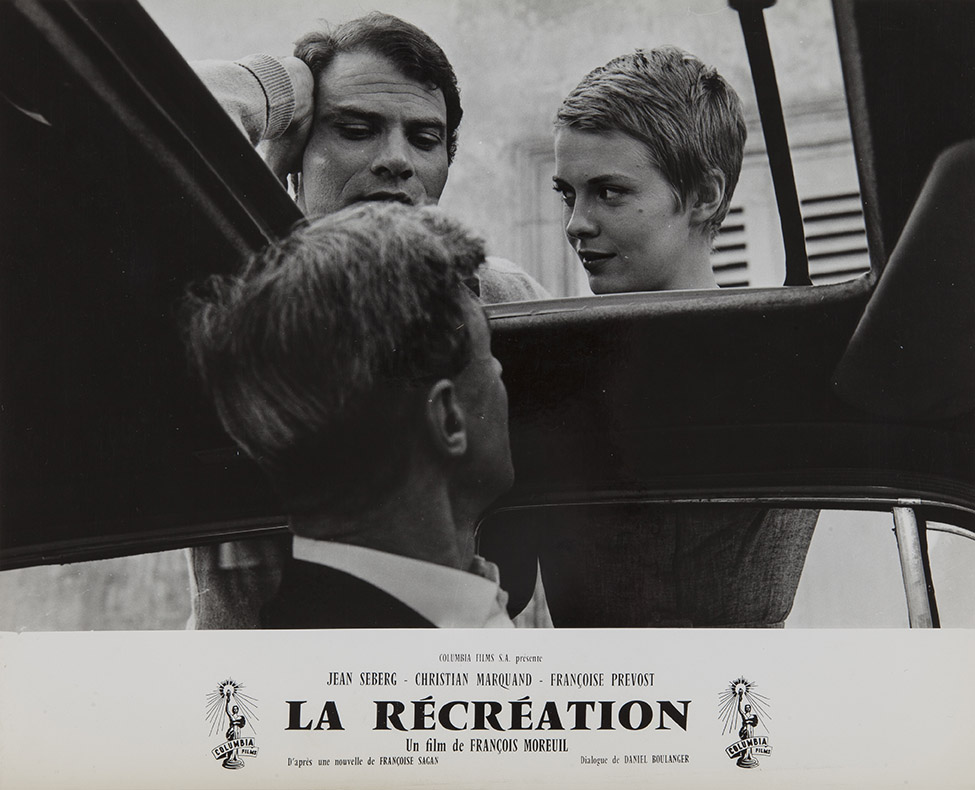

In 1959 Moreuil and Seberg visited Los Angeles and met the French Consul General Romain Gary – a novelist and French wartime hero – for dinner. When Moreuil had to return to Paris unexpectedly he asked Gary to look after his wife while he was a way: “and he did,” Moreuil once recalled, “- he sure did.” Late in 1961 Gary and Seberg moved into a spacious apartment at 108 Rue du Bac. Seberg did, however, appear in Moreuil’s film La Récréation which was released earlier that year. In 1962 they divorced and only met once more in their lives. According to Seberg, the marriage had been a ‘violent’ one and she had ‘got married for all the wrong reasons.’ Meanwhile Seberg and Gary married in a ceremony in the little Corsican village of Sarrola-Carcopino.

In an interview with a journalist in 1963: “The life of an actress is so uncertain. Just like the movie burliness. You never know what happens to a career. Some actresses get trapped in the wrong kind of role. Some turn into successes, others just fade away. I think I’ve about exhausted the possibilities of work here. Whenever I’m given a role in a French film, they have to rewrite it to make the girl an American or something to account for my French accent, which is pretty flat.”

Jean Seberg & Romain Gary marriage in Sarrola-Carcopino

Françoise Prévost and Jean Seberg in Les grandes personnes directed by Jean Valère, 1961

Romain Gary (Romain Kacew, Emile Ajar) et Jean Seberg a Rome avant le depart pour le tournage du film Congo Vivo, 1961 Neg:1070 — Romain Gary and Jean Seberg in Rome before departure for filming of Congo Vivo, 1961

Jean Seberg on the set of La récreation directed by Fabien Collin and François Moreuil, 1961

La Recreation Jean Seberg and Evelyne Ker in La Récreation directed by Fabien Collin and François Moreuil, 1961

In 1959 the couple visited Los Angeles and met the French Consul General Romain Gary – a novelist and French wartime hero – for dinner. When Moreuil had to return to Paris unexpectedly he asked Gary to look after his wife while he was a way: “and he did,” Moreuil once recalled, “- he sure did.” She and Moreuil divorced the following year and their marriage, according to Seberg, had been a ‘violent’ one and she had ‘got married for all the wrong reasons.’ Seberg did, however, appear in Moreuil’s film La Récréation which was released in 1961.

Warren Beatty and Jean Seberg in Lillith directed by Robert Rossen, 1964. It was Rossen’s last film and he died two years later.

Jacques Perrin and Jean Seberg in La ligne de demarcation directed by Claude Chabrol, 1966

Jean Seberg in Lillith directed by Robert Rossen, 1964

Jean Seberg and Maurice Ronet in La ligne de demarcation directed by Claude Chabrol, 1966

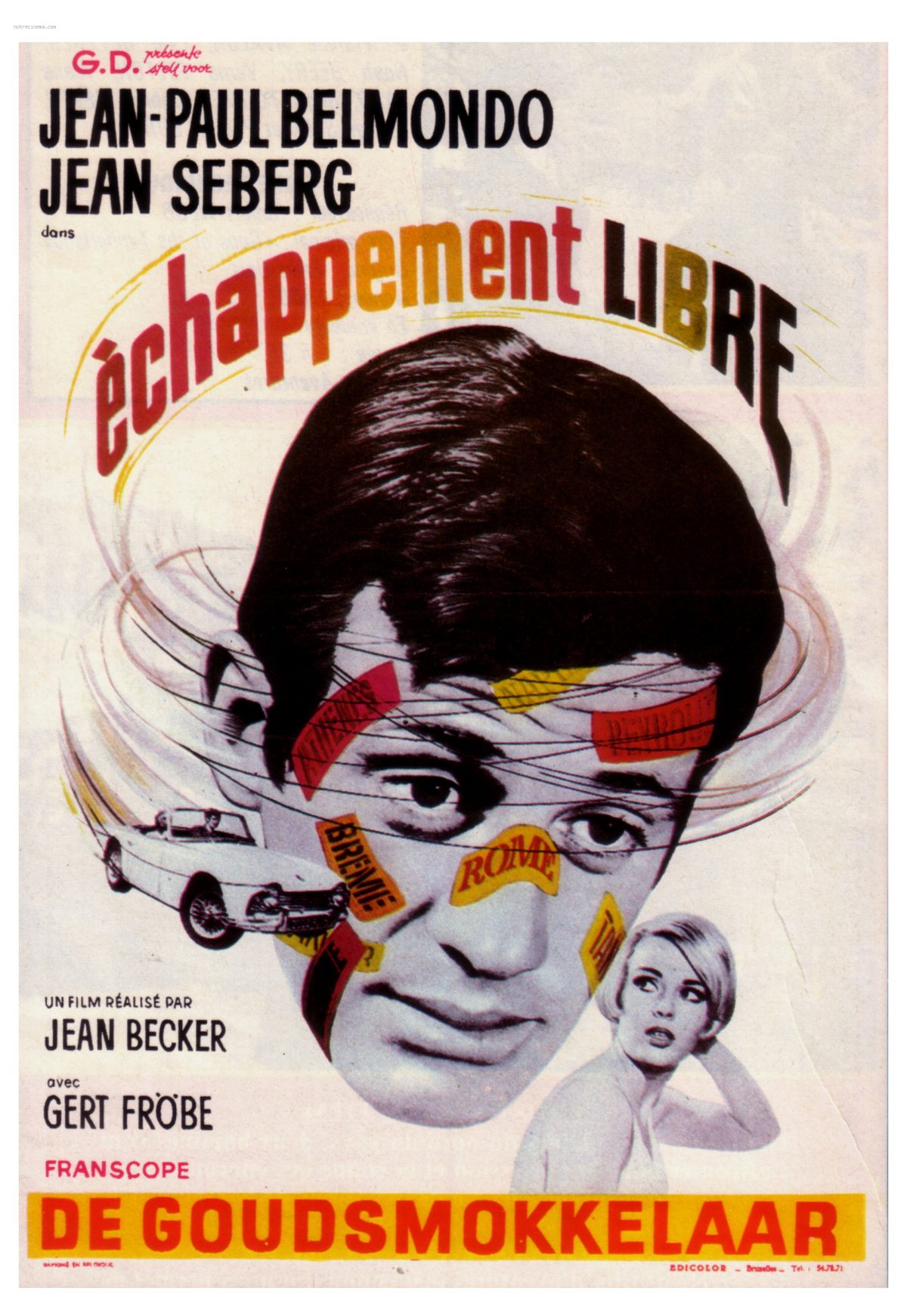

Jean Seberg in Echappement libre directed by Jean Becker, 1964

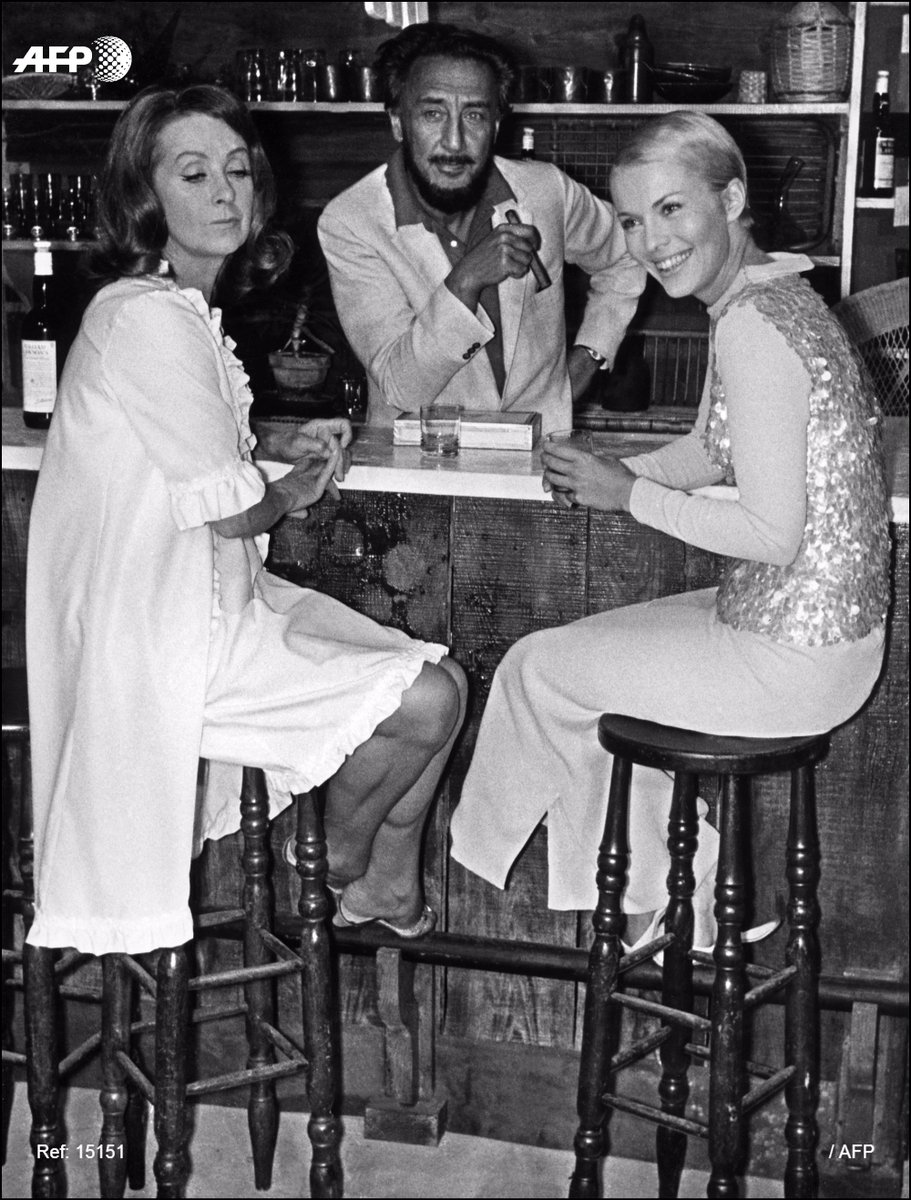

Danielle Darrieux avec Romain Gary et Jean Seberg en octobre 1967

Jean Seberg in A Fine Madness, 1966.

Jean Seberg and Claude Rich in Diamonds Are Brittle, 1965

Jean Seberg on the set of “Paint Your Wagon” – 1969.

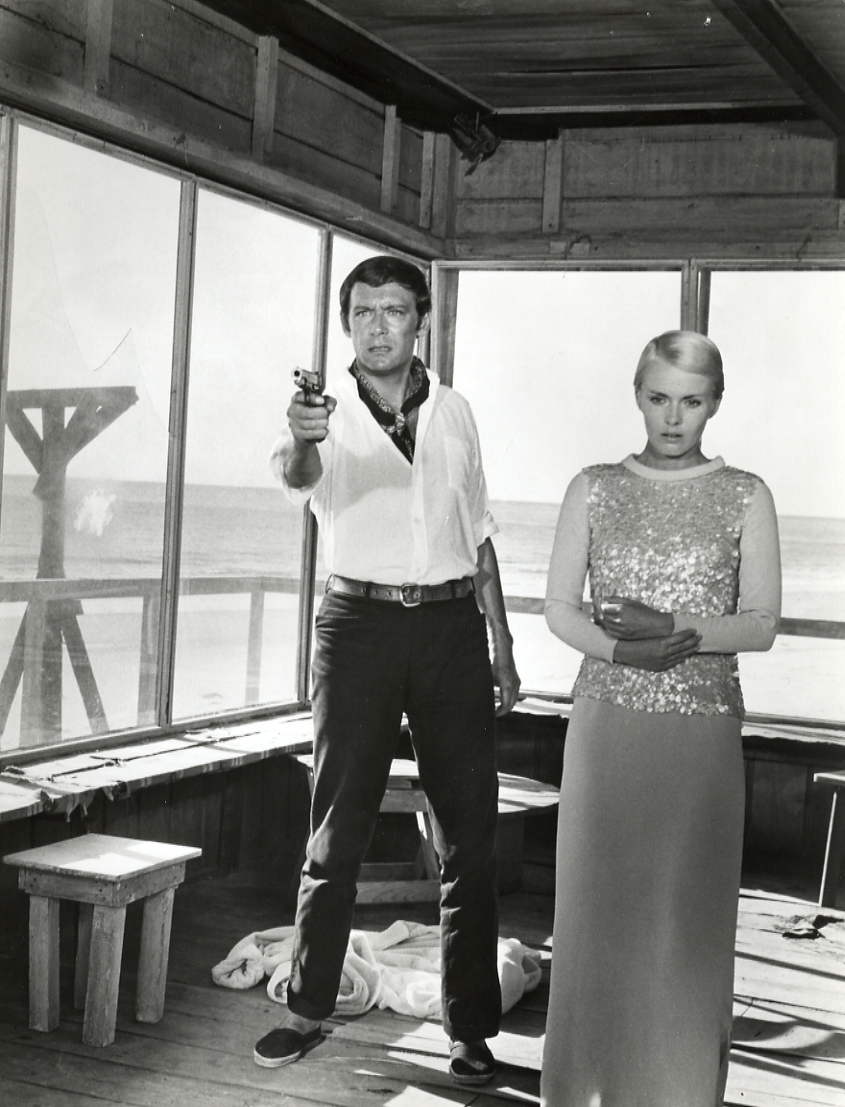

Maurice Ronet and Jean Seberg in Les oiseaux vont mourir au Pérou directed by Romain Gary, 1968

Jean Seberg and husband Romain Gary

Seberg received more good reviews in Robert Rossen’s 1964 film Lilith and she began to appear in Hollywood movies while still continuing with her European career. After completing Paint Your Wagon in the US in 1969, Seberg started helping out with the Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast Program, which provided hot meals to under-privileged children. She was soon contributing several thousand dollars in cash to the movement.

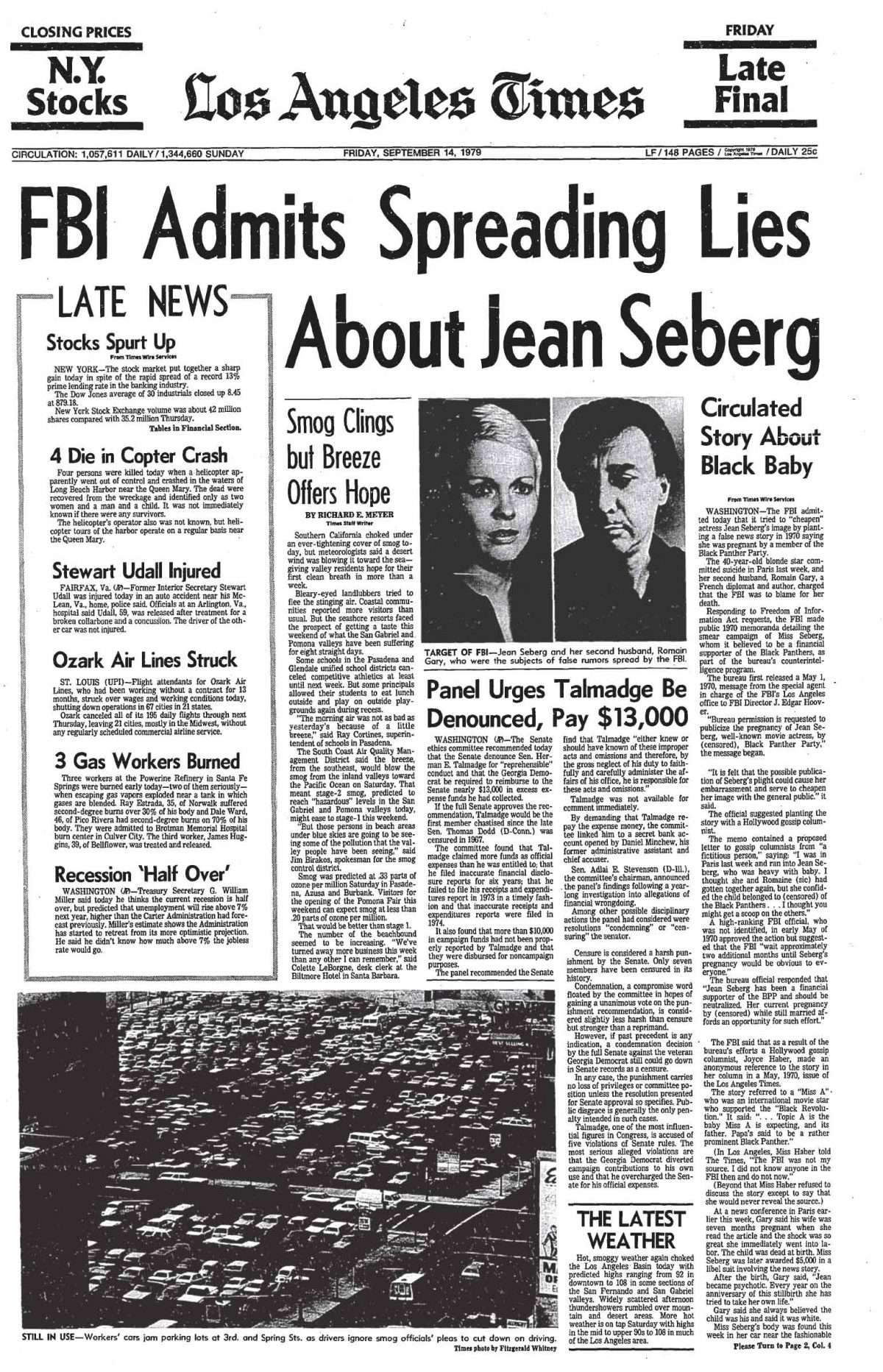

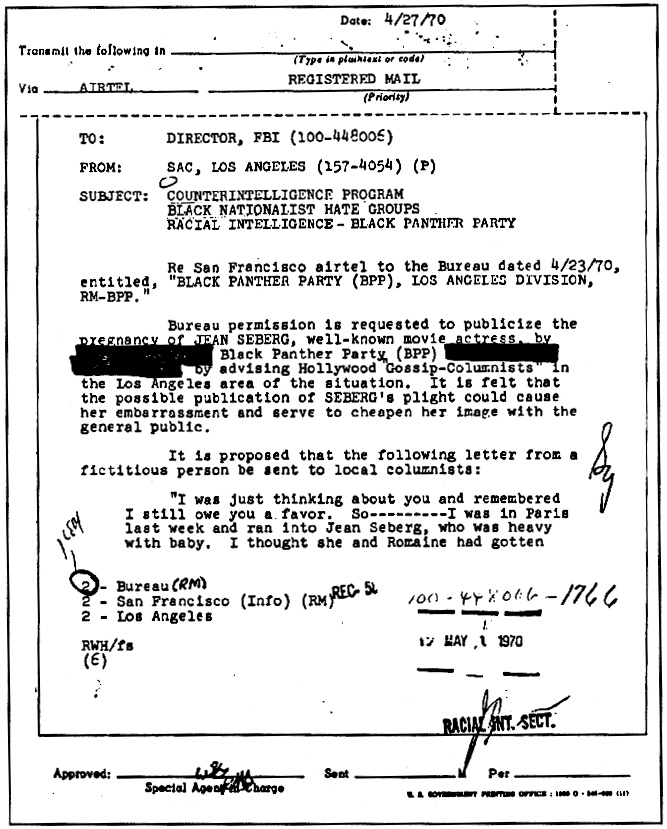

J. Edgar Hoover, at the time still Director of the FBI, thought the Black Panthers “the biggest threat to the national security” and Seberg was kept under surveillance and her telephone tapped. The FBI found out Seberg was pregnant and a rumour was planted approved by Hoover himself, that the father of the child she was expecting was ‘a black militant.” Seberg was indeed pregnant but the father was no Black Panther, nor her husband’s either but a student revolutionary she met while making a film in Mexico in 1969. Not actually naming Seberg, the rumour initially appeared in the LA Times in the summer. It gave enough clues for people to identify her: “a handsome European picked her for his wife . . . the outgoing Miss A was pursuing a number of free-spirited causes among them the black revolution . . . According [to] all those really ‘in’ international sources, topic A is the babe Miss A is expecting and its father. Papa’s said to be a rather prominent Black Panther.” On August 24 1970 Newsweek magazine named Seberg as did many other newspapers across America.

Seberg was devastated and at the end of the month she gave birth to a premature baby girl who died two days later. At the funeral in Marshalltown Seberg opened the coffin to show that the baby was white. Soon after she went to New York to talk to her lawyer. “He said suing for libel would cost $1 million and take ten years, and he asked if the bitterness was worth it. That’s when I cracked up and I was locked up.” Seberg never really recovered from the shock. Seberg and Gary divorced in less than a year later but stayed friends and they split their Parisian apartment in two. In March 1972 she married for the third time to aspiring film maker Dennis Berry, son of the director John Berry and continued living in Paris. With the exception of the TV movie Mousey never worked in the US again.

During this time there were more periods of ‘mental instability’ and she started to depend more and more on prescription drugs, alcohol and and hangers-on: “I like to have friends laughing around me, and I like good food and good wine – so what if I’m the only one who can afford to pick up the check?”

On September 10 1979 the day after Seberg’s autopsy, Gary called a press conference and made the claim that the FBI was responsible for Seberg’s death. The action they had taken to discredit her because of her financial support for the Black Panthers had caused her to repeatedly attempt to take her own life often on the anniversary of her daughter’s death. According to her friends interviewed after her she had died, she experienced years of aggressive surveillance, as well as break-ins and other intimidation-oriented activity.

On the evening of December 2, 1980 Romain Gary, Seberg’s former husband, also ended his life with a carefully planned bullet to the head. His suicide note urged that “devotees of broken hearts” should look elsewhere. Many of his friends and associates, however, had little doubt that the Seberg’s death had enormously upset him.

Francois Truffaut who wrote the original treatment for A Bout de Souffle tried to hire Seberg for his film Day for Night in 1973 but it was at the time of another low point in her life and he was unable to get in touch with her. He wrote of Seberg in 1958 at a time when most of the world seemed to be laughing at her:

Her “wide-open blue eyes” have “a glint of boyish malice” and “when Jean Seberg is on screen you can’t look at anything else. Her every movement is graceful, each glance is precise. The shape of her head, her silhouette, her walk, everything is perfect; this kind of sex appeal hasn’t been seen on the screen.”

Bob Willoughby, Jean Seberg at the Loire (at the set of ‘Saint Joan

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.