Some writers have a tendency to mythologise their lives, which is perhaps understandable as their trade is fiction.

Barrie Keeffe claimed he was inspired to write the The Long Good Friday after he “took a Saturday morning drive around the East End, looking at Docklands and this hideous memorial to Thatcherism, Canary Wharf. I hate Docklands. The first seeds of the story came from that anger.”

Good heart, good copy, but hardly true. Keeffe wrote the first draft of The Long Good Friday four weeks before Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in May 1979. Moreover, that memorial to Thatcherism, Canary Wharf, wasn’t developed until five years after the movie’s release while most the buildings (including One Canada Square) were not completed until the 1990s.

Producer Barry Hanson asked Keefe to write a script for a TV series called The Last Thriller sometime in the late 1970s. Hanson loved gangster movies and wanted Keeffe to write something like a modern version of Nic Roeg‘s Performance. Keeffe delivered a script called The Paddy Factory which turned on the idea of a opportunistic but ruthless East End gangster confronted by unrelenting force of political belief in the form of the IRA. Or as Keeffe described it “terrorism meets gangsterism”. Hanson liked the script and thought it had the potential to make a good movie.

Barrie Keeffe was an established theatre and television writer. He wrote political, social, provocative and often prescient dramas about class, race, and the fragmentation of society. His plays included Gotcha (1976) about a disaffected schoolboy holding a teacher hostage; Barbarians (1977) about youth unemployment; Gimme Shelter (1977) examined class; and SUS about institutional racism within the Police.

For BBC’s Play for Today he wrote Nipper (1977) about a teenager’s life of crime; and Waterloo Sunset (1979) which starred legendary Londoner Queenie Watts as a woman who flees her retirement home to visit the streets of her youth.

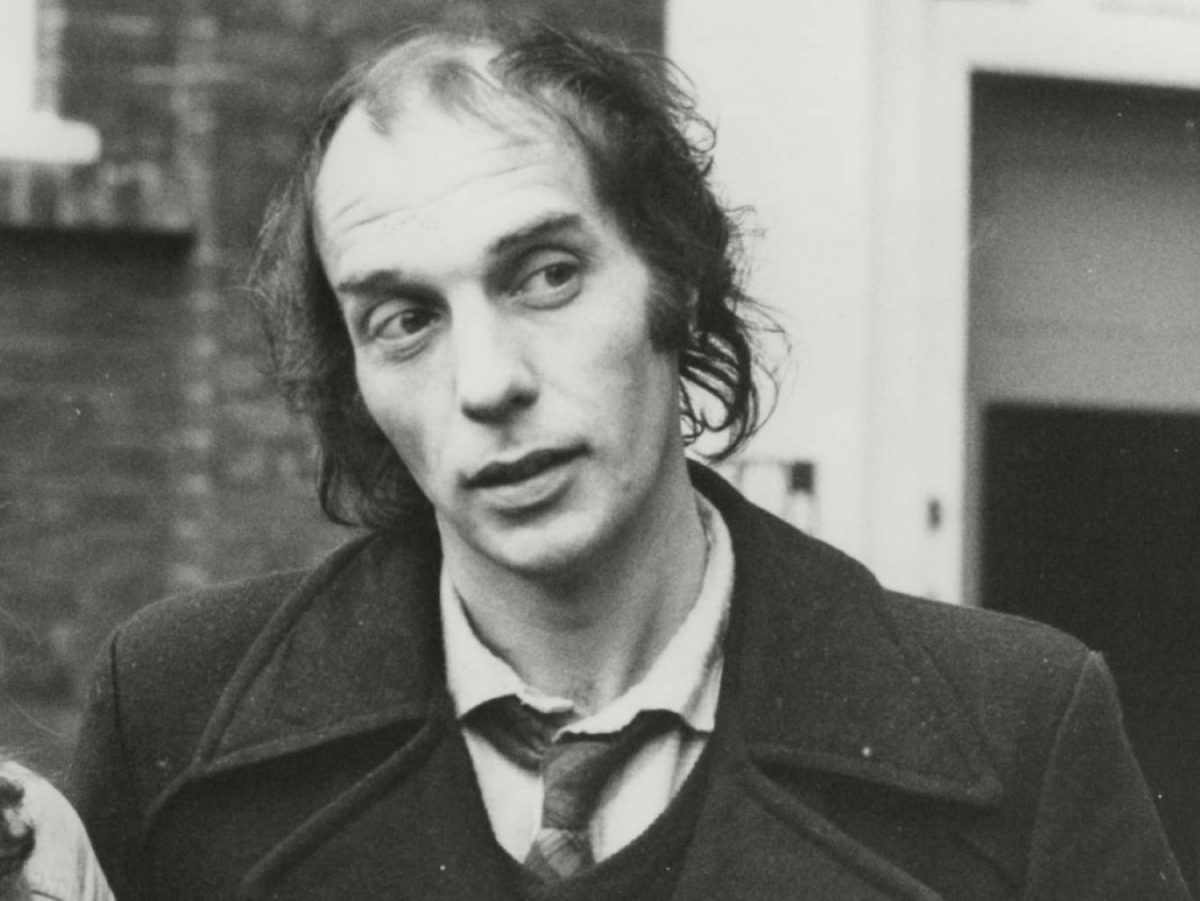

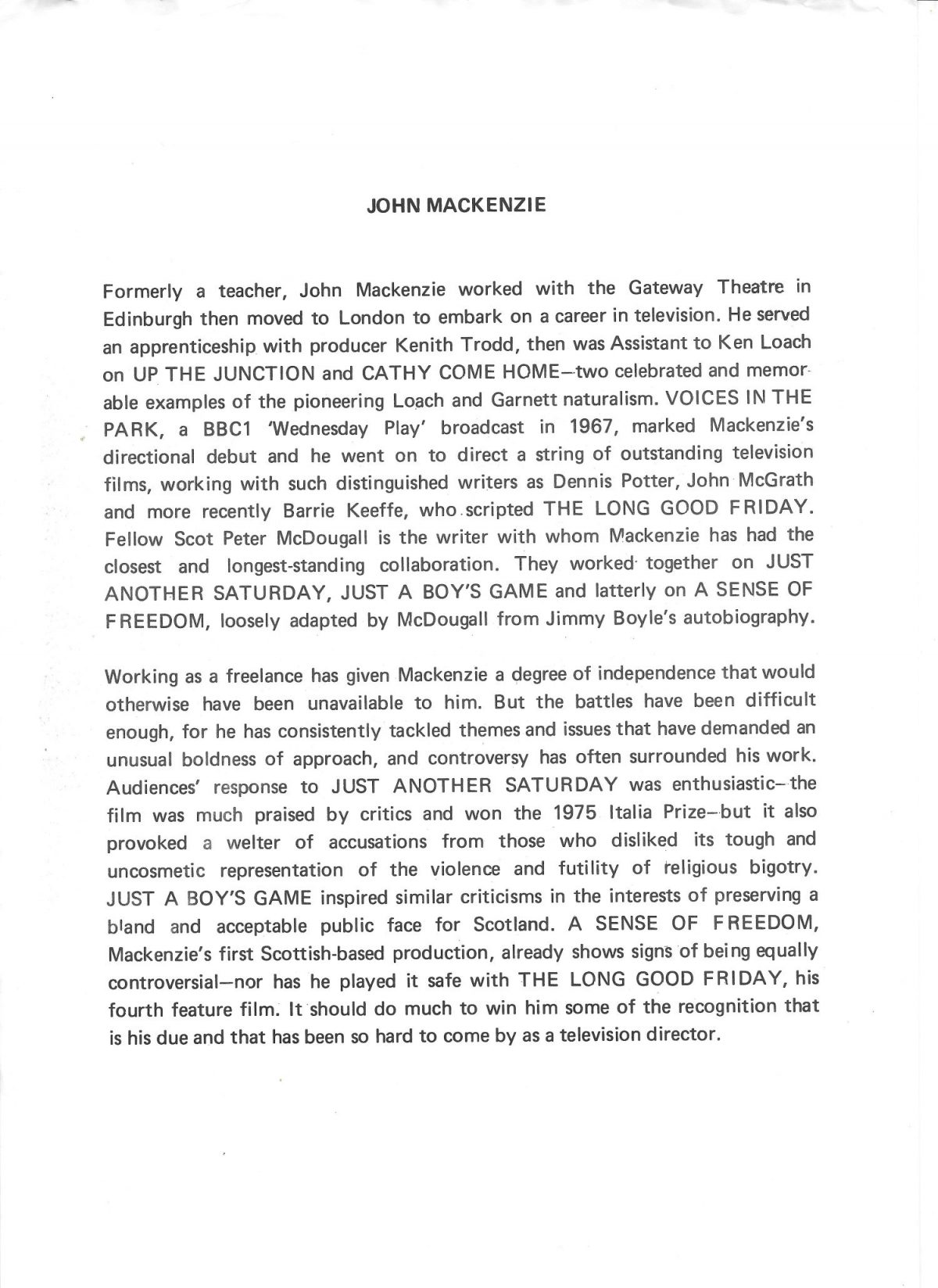

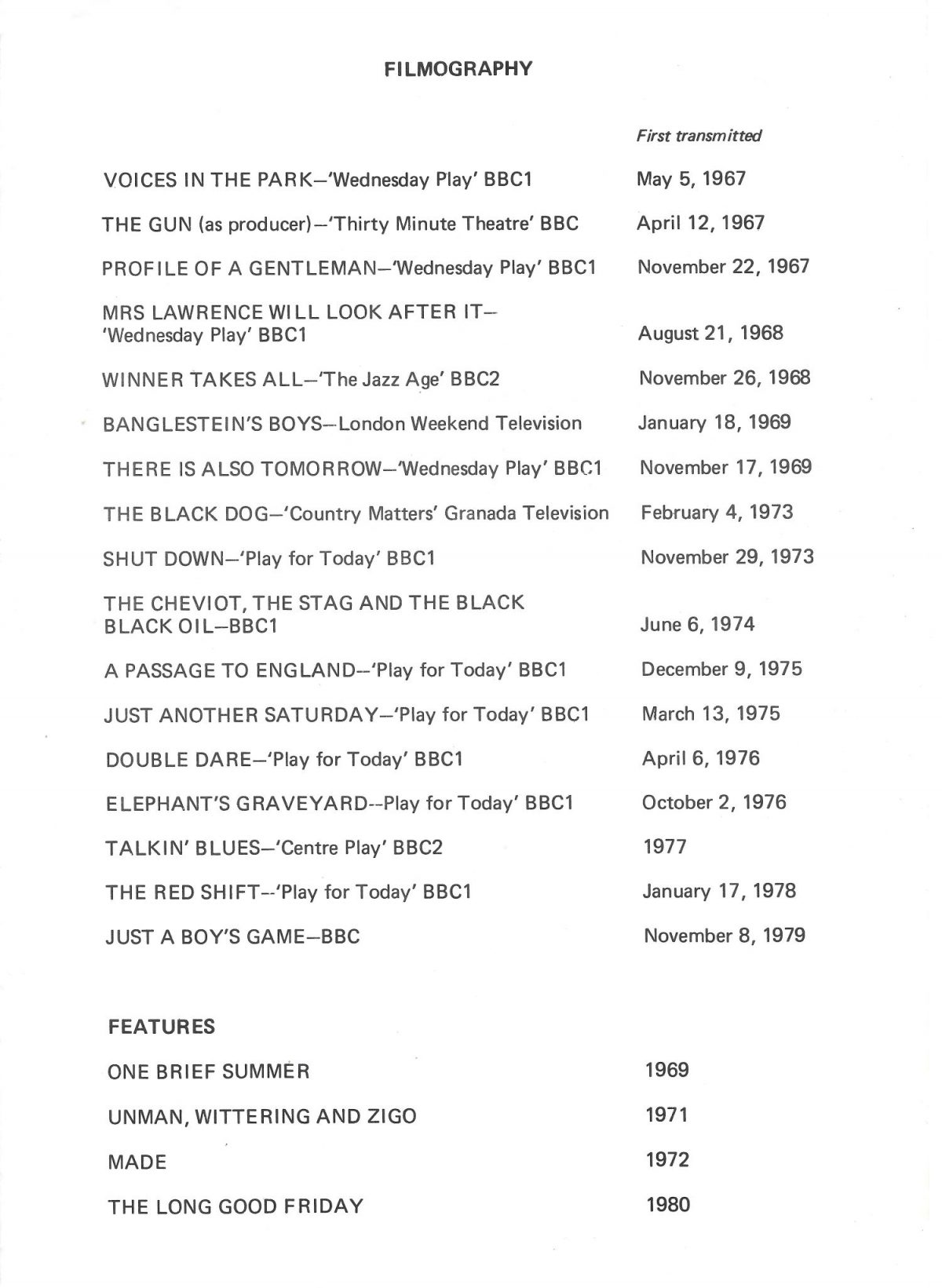

Hanson bought the rights to Keeffe’s script and took it with him when he left television to set-up Calendar Films. Hanson brought in John MacKenzie to direct. MacKenzie was an award-winning director with two feature films to his credit and a series of acclaimed TV dramas written by Peter McDougall Just Another Saturday (1975), The Elephant’s Graveyard (1976) and Just A Boy’s Game (1979). MacKenzie liked Keeffe’s script but thought it needed work: “….the essence of the story was there. The Docklands backdrop and the Mafia involvement was there already but I wanted to embed the IRA into the back story a lot more. Their presence tapped into a deeper theme: the struggle between a freelance gangster and idealists.”

However, MacKenzie disliked the title The Paddy Factory and insisted on calling the film The Long Good Friday until it stuck.

Hanson chose Bob Hoskins to star as the yet unnamed East End gangster. Hanson and Keeffe met with Hoskins at a hospital for tropical disease where the actor was having a “26-foot tape worm removed.” Hoskins had ingested the worm while filming Zulu Dawn in South Africa. According to Hanson this worm had a foot added to its length every time Keeffe retold the story. Hoskins liked the script but thought it needed to be fleshed out.

Hoskins came up with the name Harold Shand for his character. Hoskins improvised Shand’s character based on his knowledge of East End gangsters. According MacKenzie, Hoskins was firing one idea after another which were then given to Keeffe to develop.

Helen Mirren was cast as Shand’s girlfriend Verina. Mirren liked the script but thought Verina cliched and dull. She agreed to take the role on one condition: that her character was rewritten and developed. Originally Verina was a mousy, quiet moll. She only opened her mouth once to show a set of rotten teeth. Like Hoskins, Mirren began suggesting ideas for her character. Verina became Victoria. She was no longer a quiet working class girl but a smart middle class woman who was as tough and as complex as Harold Shand.

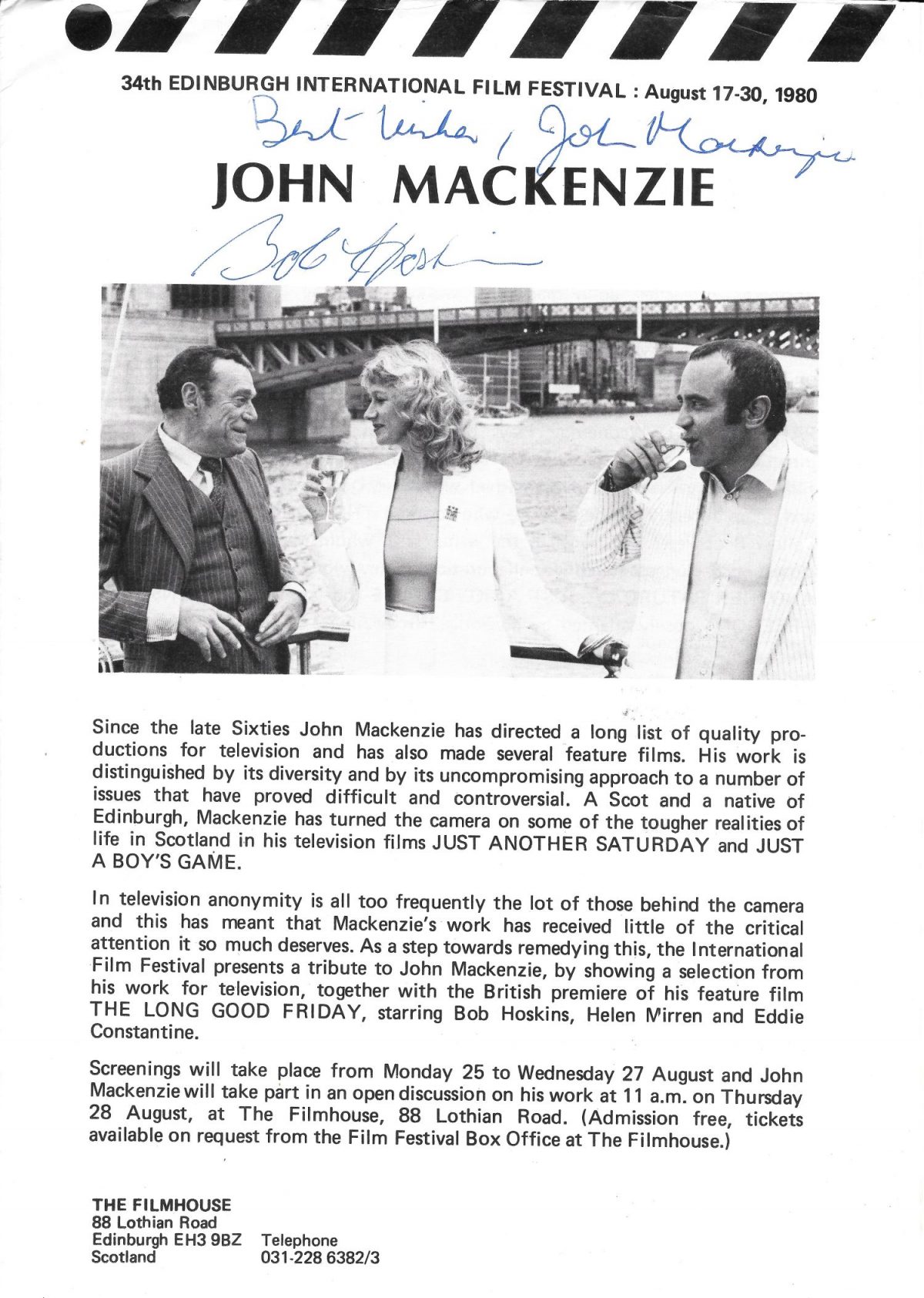

Tuesday 26th August 1980: I was at the premiere screening of The Long Good Friday during the 1980 Edinburgh Film Festival. I bought tickets because I liked Barrie Keeffe’s work, and hoped he might be in attendance. I also knew Hoskins work through Pennies from Heaven and the adult literacy series On the Move. I had little thought about him but certainly more about John MacKenzie who had directed three brilliant scripts by Peter MacDougall. All unimportant but necessary to explain why I was there: for the writer not the director or star.

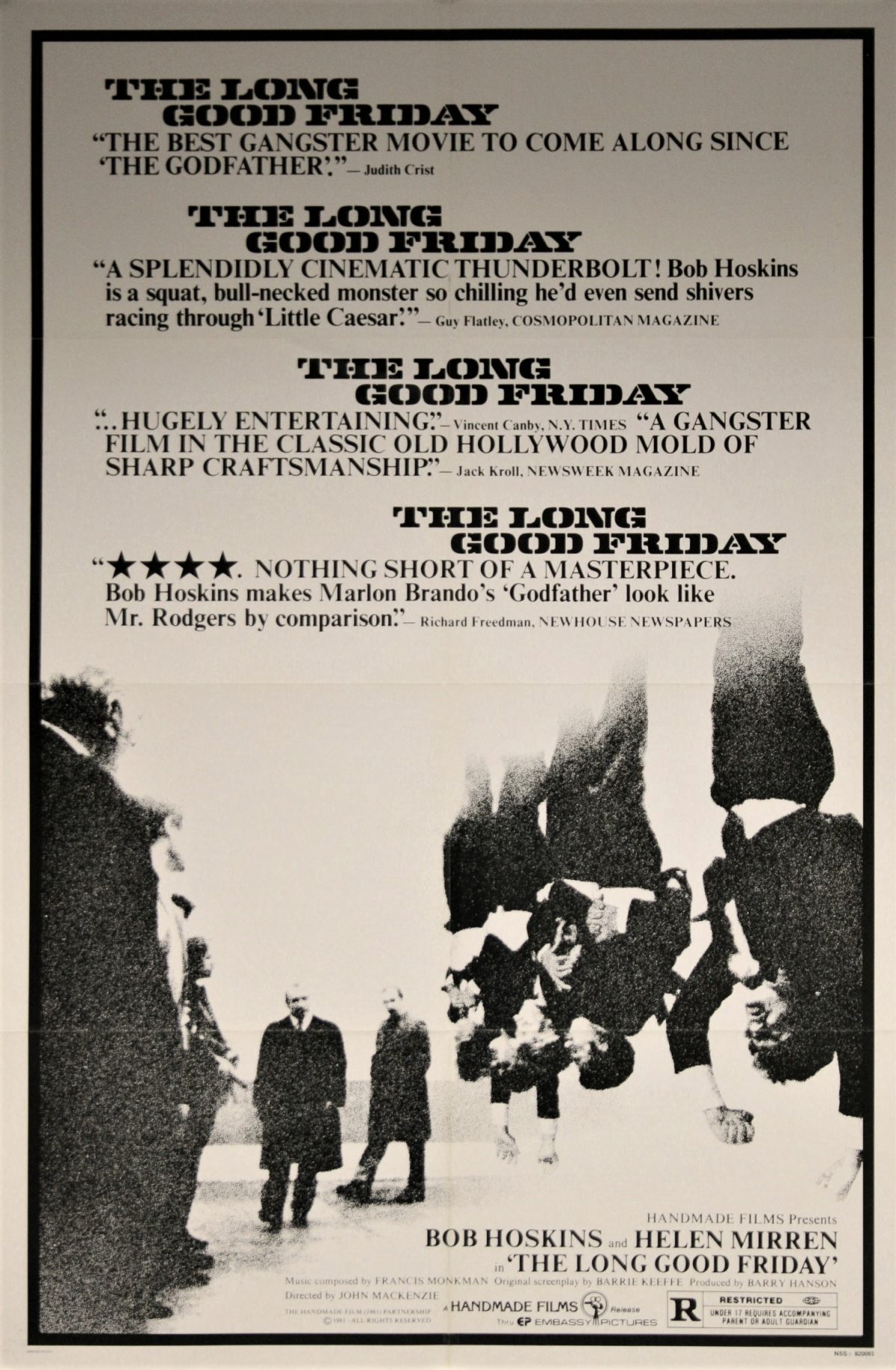

Over the next 114-minutes that changed. I watched a film which is in many respects one of the greatest British movies every produced. MacKenzie in black leather jacket, red shirt and jeans alongside a white shirted, leather-jacketed Bob Hoskins introduced the film. Hoskins said: “There it is, I hope you enjoy it.”

With its quiet, unexplained opening set in Ireland the film progressed to a complex, bloody and brutal finale with an end sequence which delivered an acting class from Bob Hoskins.

As the end titles rolled, a small but vociferous group booed the movie for its perceived suggestion of an IRA victory. Hoskins and MacKenzie sat behind my brother and myself during the screening. On the way down the stairs both were in front of us. Hoskins turned and asked, “Hey lads, what did you you think of it? Did you think we were selling the IRA?” MacKenzie piped up: “I don’t get the booing. Do you think it was an IRA film?” My brother and I assured them it wasn’t but what a brilliant film and a brilliant performance, etc, etc. Hoskins said, “That’s really nice lads, thanks.” Both signed our programmes. Then MacKenzie said, “I don’t get Edinburgh audiences.” We chatted about the film on the way down the stairs and then outside the cinema on Lothian Road until a taxi cab picked both men up. Before getting in the cab Hoskins turned and said: “Here, fancy coming for a beer, the hotel’s just up the road?” Alas, to my deep regret, my brother and I had a last bus to catch home.

The boos of a tiny part of The Long Good Friday‘s audience at the Edinburgh Festival reflected the fears of the movie’s main producer Sir Lew Grade.

Grade was one of the greatest TV producers ever. The man behind Danger Man, The Prisoner, The Champions, Randall and Hopkirk [Deceased], Department S, Jason King, Strange Report and many, many others. Although he had many, many successes, he also had the occasional failure. At the time of The Long Good Friday, Grade was losing a shedload of money on his film Raise the Titanic. Grade feared The Long Good Friday with its associations to the IRA would destroy his company. He decided to re-custom the film as a TV movie. Edit out the IRA connections and re-voice Hoskins as a gangster from Birmingham. Why Birmingham? No one knows.

Fortunately, Hoskins had a clause in his contract which forbade his voice being replaced by anyone but himself in a re-cut. Which meant the film was now in Limbo.

Grade (foolishly) wanted rid of this possible death blow, which proved lucky for MacKenzie. At a party he met George Harrison. He told him about the film and what was happening to it. Harrison liked the what he heard and bought the film off Grade for around one million pounds. The death blow Grade feared was (sadly) inflicted by himself. If he had stopped listening to his advisors (which had grown in size with his success) then Grade would have had another winner on his hands. Instead Harrison won out and his production company Handmade Films scored one of their biggest successes.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.