Michael Prince is a photographer, producer, and filmmaker. He is one of the most creative photographers working today, who has a knack for making an image steal the breath, pop the hairs, and linger in the ole meme bank long after it’s first scanned.

Now, this may sound biased so I’ll ‘fess up. Yep, I have known Michael for a long, long time, since we both worked together in television some twenty-odd years back. I was what some politely called “a maverick.” Kind of them to be sure, but I honestly didn’t give a fuck, and that was probably the problem. But Michael was a real talent, who when we first met was kinda wasting away working in graphics, when his real passion was taking pictures and making films. Thankfully, he made the move and landed happily directing programmes for the tube.

We kept in touch. We lost touch. While I drifted, Michael swam straight for the shore towards new land where X-marked the spot and all the best treasure was buried. He knew what he wanted and where he was going. Over the years, Michael built up a photographic portfolio of such high quality that most serious photographers would give their one good eye for.

Now one day, while browsing through social media, I parked in front of a series of black & white photographs someone had shared that did the very things I wrote about above. Breath-taking shots taken with a pinhole camera of wild Scottish countryside. I had no idea who had made these pictures but I became fan. Then, when I found out they were by some bloke I once knew in the last century, I felt tremendous joy at his talent and success. Not that I would ever have told him this. I doubt I would have even liked his pictures on social media in case he ever found out. But I quietly followed his career and watched this real talent produced better and greater work than I ever thought possible. But that sez more about my lack of imagination than the quality of work produced by the artist I’m writing about.

Prince’s photographic work has been exhibited across the country, published in books and magazines, and has even been seen on television. In 2019, he produced and directed a quirky and original short film about Ernest Whiteley & Co. Ladies outfitters in Bridlington, Yorkshire, an emporium which “has hardly changed since it first opened its doors in 1901.”

Mrs Anne Clough the granddaughter of the original owner describes working in the shop since 1960 when she was 27 years old.

The shop mannequins have been here since the 1930s. Their classic ‘no nonsense’ outfits, along with much of Whiteley’s other stock, including brassiers and hundreds of pairs of large ladies knickers can be extremely hard to find these days, attracting regular customers from all over Britain.

Prince made the film in September 2019 as an accompaniment to his forthcoming photographic portrait book Mannequin Heaven. I contacted him to find out more about his film and his interest in mannequins, and this was his reply.

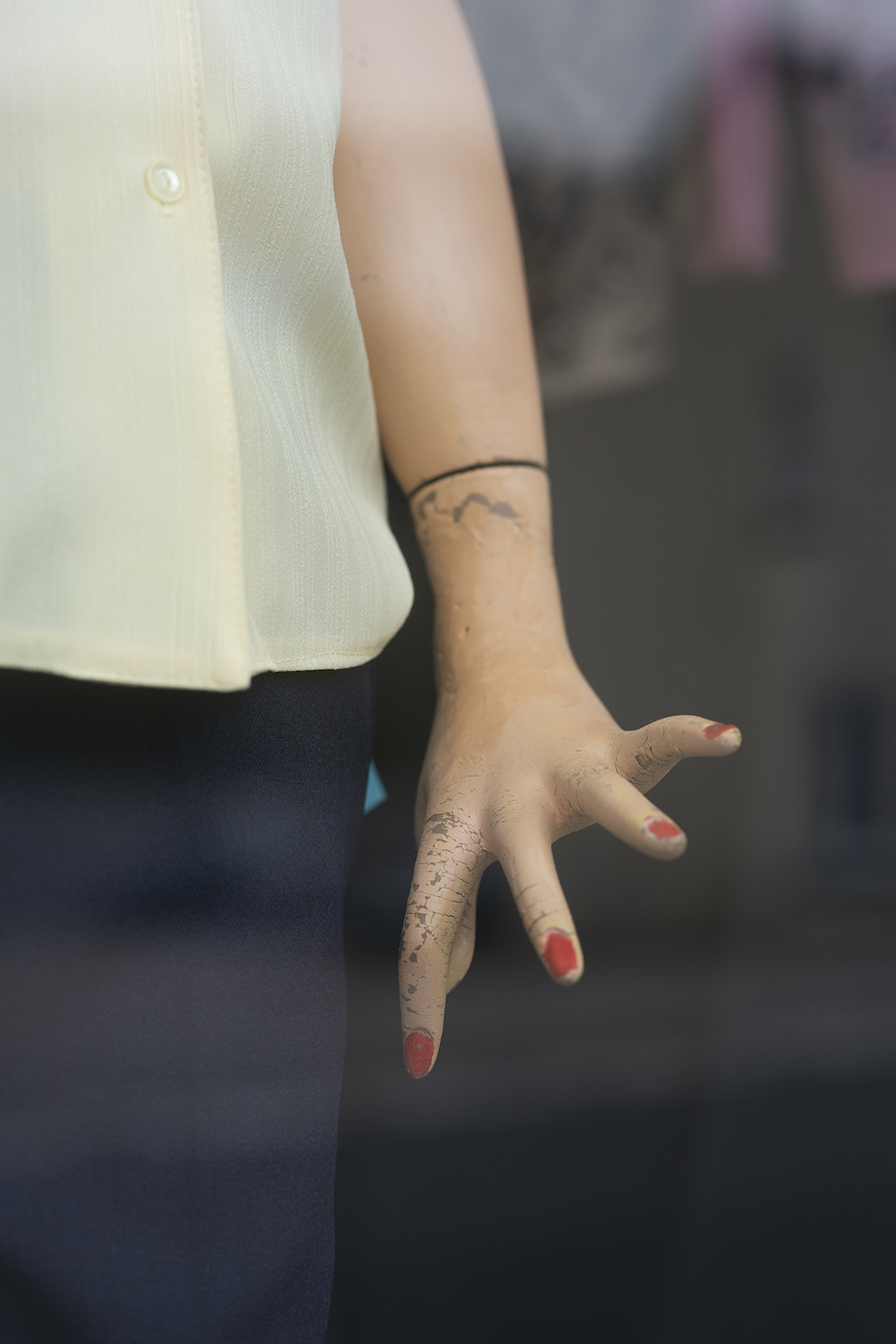

Michael Prince: I’ve always had a fascination and fondness for old mannequins, their awkward and unnatural poses, frozen expressions, and faded beauty… you may know the ones, mostly wearing a second-hand dress, complete with an ill-fitting wig and occasionally a sellotaped wrist. I’d glimpse them now and again, maybe in a charity shop or in a window of a family business selling women’s or menswear, a drapers, a tailors, or wool shop – at the forgotten end of the high street – often in smaller ‘out of the way’ towns. If I was incredibly lucky the shop would still be open for business, orange gel on the inside of the window to protect its contents from the sunlight with three or four mannequins still at work. The clothing assistant or owner is willing to talk about the history of the family business, but then explains that online shopping has killed of their trade and the future is uncertain.

Today’s high streets are ultimately characterless and depressing places where vaping, tattooing, nail bars and betting shops rule. In the windows of the retailers that sell us clothes there is the modern want for featureless and headless mannequins. You see these rows of blind souls everywhere. It’s as if fashion designers, window dressers and retailers have forgotten the art of a real mannequin, the sophistication that they bring, the selling power they possess – it’s in their dna. Instead proper mannequins have become exiled to the margins, confined to the edges of the high street.

Michael Prince: A few years ago, I set out with my camera to document the remaining real mannequins on the British high street by making portraits of them before they are cruelly dismantled and permanently retired.

I see them as an enslaved workers, trapped by their elegance and beauty into the rag trade, sealed behind glass to sell, constantly staring out at the real world, but never able to partake – only able to experience life in seconds at a time through the real lives of others that pass by their windows.

Through my portraits I focus in on their timeless beauty, their expressions and sophistication, their love for life is clear in their painted eyes. I can sense their desire and longing to be real, to be noticed, to be loved. I’ve included the reflections in the glass that imprisons them to create spaces, an alternate reality and possibly a moment that enables the mannequins to step into our world. Once freed they appear to be just like us. You might never notice them.

Their seasons change, years pass into decades, and yet they remain ageless, fixed and frozen in fashion – dutifully and relentlessly carrying on with their work; a summer dress to be sold, a reduced-price coat, a wedding outfit, a hat for the races, a school uniform on sale.

The demands of a mannequin’s working life take’s its toll as they are repeatedly dressed and undressed, rearranged and repositioned – they can often become damaged, some even lose limbs. The loss of a finger or arm is a common injury, yet nothing is said or done. Repairs are rare. A broken wrist is mended with tape and eye lashes are stuck back on. I’ve witnessed this harsh treatment close up, the scars and marks on hands and faces.

Sadly, these old shops and real mannequins are disappearing from our high streets, thousands have already been cast aside, lost forever to the blandness of modern times. Mannequin Heaven is my document and tribute to those that have stood the test of time and survived to give their lives for fashion.

‘Mannequin Heaven’ will be published in Spring 2020. See more of Michael Prince’s work here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.