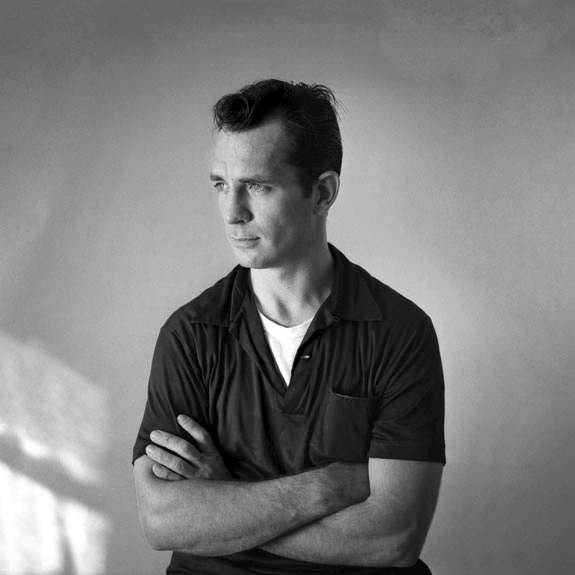

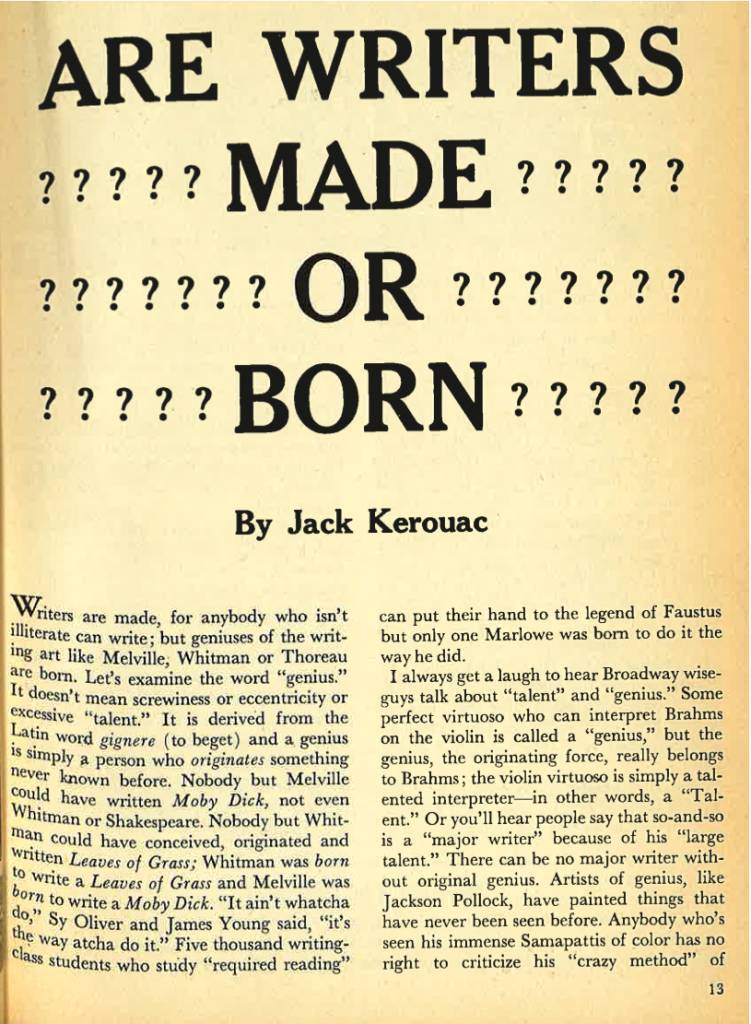

Jack Kerouac’s 1962 essay for Writer’s Digest “Are Writers Made or Born?” begins:

Writers are made, for anybody who isn’t illiterate can write; but geniuses of the writing art like Melville, Whitman or Thoreau are born.

What is genius? British novelist Amelia E. Barr was succinct, writing in 1901: “Genius is nothing more nor less than doing well what anyone can do badly.”

Is genius competitive, nirvana for competitive intelligence tests taken by people-pleasing children and needy adults who like to score their brains? Can you become a genius on a points decision?

Barr advocated hard work and a thick skin in her fuller 9 Rules for success:

*Men and women succeed because they take pains to succeed. Industry and patience are almost genius; and successful people are often more distinguished for resolution and perseverance than for unusual gifts. They make determination and unity of purpose supply the place of ability.

*Success is the reward of those who “spurn delights and live laborious days.” We learn to do things by doing them. One of the great secrets of success is “pegging away.” No disappointment must discourage, and a run back must often be allowed, in order to take a longer leap forward.

*No opposition must be taken to heart. Our enemies often help us more than our friends. Besides, a head-wind is better than no wind. Who ever got anywhere in a dead calm?

*A fatal mistake is to imagine that success is some stroke of luck. This world is run with far too tight a rein for luck to interfere. Fortune sells her wares; she never gives them. In some form or other, we pay for her favors; or we go empty away.

*We have been told, for centuries, to watch for opportunities, and to strike while the iron is hot. Very good; but I think better of Oliver Cromwell’s amendment — “make the iron hot by striking it.”

*Everything good needs time. Don’t do work in a hurry. Go into details; it pays in every way. Time means power for your work. Mediocrity is always in a rush; but whatever is worth doing at all is worth doing with consideration. For genius is nothing more nor less than doing well what anyone can do badly.

Be orderly. Slatternly work is never good work. It is either affectation, or there is some radical defect in the intellect. I would distrust even the spiritual life of one whose methods and work were dirty, untidy, and without clearness and order.

*Never be above your profession. I have had many letters from people who wanted all the emoluments and honors of literature, and who yet said, “Literature is the accident of my life; I am a lawyer, or a doctor, or a lady, or a gentleman.” Literature is no accident. She is a mistress who demands the whole heart, the whole intellect, and the whole time of a devotee.

*Don’t fail through defects of temper and over-sensitiveness at moments of trial. One of the great helps to success is to be cheerful; to go to work with a full sense of life; to be determined to put hindrances out of the way; to prevail over them and to get the mastery. Above all things else, be cheerful; there is no beatitude for the despairing.

*Apparent success may be reached by sheer impudence, in defiance of offensive demerit. But men who get what they are manifestly unfit for, are made to feel what people think of them. Charlatanry may flourish; but when its bay tree is greenest, it is held far lower than genuine effort. The world is just; it may, it does, patronize quacks; but it never puts them on a level with true men.

It is better to have the opportunity of victory, than to be spared the struggle; for success comes but as the result of arduous experience. The foundations of my success were laid before I can well remember; it was after at least forty-five years of conscious labor that I reached the object of my hope. Many a time my head failed me, my hands failed me, my feet failed me, but, thank God, my heart never failed me.

So. No genius without dedication.

What of inspiration?

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky wrote to his benefactress, Nadezhda von Meck on March 17th, 1878 (from The Life & Letters of Pete Ilich Tchaikovsky): (The pair never met. ‘They implicitly agreed never to meet in person. ”My ideal man is a musician,” she wrote. But ”I am afraid to meet you; I don’t think I would be able to say anything to you.” Tchaikovsky replied: ”You are afraid not to find in me those qualities which your idealizing-inclined imagination has attributed to me. And you are quite right.”’)

Tchaikovsky wrote:

Do not believe those who try to persuade you that composition is only a cold exercise of the intellect. The only music capable of moving and touching us is that which flows from the depths of a composer’s soul when he is stirred by inspiration. There is no doubt that even the greatest musical geniuses have sometimes worked without inspiration. This guest does not always respond to the first invitation. We must always work, and a self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood. If we wait for the mood, without endeavouring to meet it half-way, we easily become indolent and apathetic. We must be patient, and believe that inspiration will come to those who can master their disinclination.

A few days ago I told you I was working every day without any real inspiration. Had I given way to my disinclination, undoubtedly I should have drifted into a long period of idleness. But my patience and faith did not fail me, and to-day I felt that inexplicable glow of inspiration of which I told you; thanks to which I know beforehand that whatever I write to-day will have power to make an impression, and to touch the hearts of those who hear it. I hope you will not think I am indulging in self-laudation, if I tell you that I very seldom suffer from this disinclination to work. I believe the reason for this is that I am naturally patient. I have learnt to master myself, and I am glad I have not followed in the steps of some of my Russian colleagues, who have no self-confidence and are so impatient that at the least difficulty they are ready to throw up the sponge. This is why, in spite of great gifts, they accomplish so little, and that in an amateur way.

No inspiration withour perspiration. Keroauc had flair. But how much of it was by design?

In Odd Type Writers: From Joyce and Dickens to Wharton and Welty, the Obsessive Habits and Quirky Techniques of Great Authors, we read how Kerouac wrote On The Road on one long enormously long reel of paper. No pauses required. Just type and type and type. The great work was not spontaneous, of course. It was the product of much thinking, plotting and noting. When the scroll was finished, Kerouac handed it to editor Robert Giroux:

To [Kerouac’s] dismay, Giroux focused on the unusual packaging. He asked, “But Jack, how can you make corrections on a manuscript like that?” Giroux recalled saying, “Jack, you know you have to cut this up. It has to be edited.” Kerouac left the office in a rage. It took several years for Kerouac’s agent, Sterling Lord, to finally find a home for the book, at the Viking Press.

It could not be cut up. You see, the book had come from God:

Unfurling the scroll, Jack “tossed it right across the office like a piece of celebration confetti.” Giroux remembers him saying, “And here it is! Written by the Holy Ghost!”

Darrin M. McMahon notes in Divine Fury: A History of Genius (via):

“I want to know how God created the world,” Einstein once observed. “I want to know his thoughts.” It was, to be sure, a manner of speaking, like the physicist’s celebrated line about the universe and dice. Still, the aspiration is telling. For genius, from its earliest origins, was a religious notion, and as such was bound up not only with the superhuman and transcendent, but also with the capacity for violence, destruction, and evil that all religions must confront.

Kerouac had created a new thing. As Joyce Johnson recalls:

On the January night in 1957 when we first met, I’d heard about Jack’s homemade scroll—how he’d used it to break through to a new way of writing (“spontaneous bop prosody,” Allen Ginsberg later called it) that enabled him to do the entire book in 20 days without stopping to put a new page in the typewriter and barely changing a word. “First thought, best thought,” Jack told me sternly, after learning that I constantly revised my own writing. As if to drive the point home, he would fish my discarded pages out of the trash and use the backs of them himself…

In the media blitz ignited by the Times review, the public heard a great deal about that scroll. It quickly became a major component of the story behind the book, and over the years, with the scroll locked away from sight, the impression grew that great violence had been done to this outlaw classic by the editors who had worked on it, that the scroll version lost to the public was far more experimental than the text of the printed book—even written in such a radically different style that there was no punctuation at all; some believed the scroll contained messages and revelations that had subsequently been suppressed. “The sadness that this was never published in its most exciting form—its original discovery,” Allen Ginsberg lamented in The Village Voice as early as 1958, “but hacked and punctuated and broken—the rhythms and swing of it broken—by presumptuous literary critics in publishing houses. The original mad version is greater than the published version, the manuscript still exists and someday when everybody’s dead will be published as it is.”

So. To Kerouac’s view on genius:

[Genius] doesn’t mean screwiness or eccentricity or excessive “talent.” It is derived from the Latin word gignere (to beget) and a genius is simply a person who originates something never known before. Nobody but Melville could have written Moby-Dick, not even Whitman or Shakespeare. Nobody but Whitman could have written Leaves of Grass; Whitman was born to write Leaves of Grass and Melville was born to write Moby-Dick.

Is talent also genius?

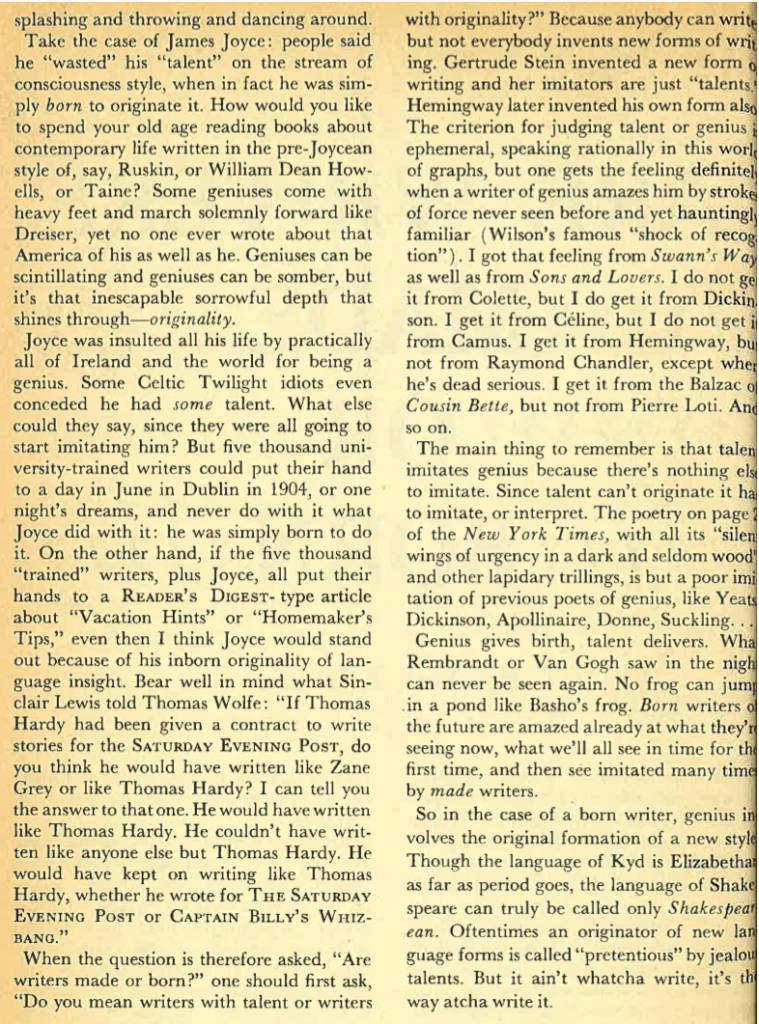

Some perfect virtuoso who can interpret Brahms on the violin is called a “genius,” but the genius, the originating force, really belongs to Brahms; the violin virtuoso is simply a talented interpreter — in other words, a “Talent.” Or you’ll hear people say that so-and-so is a “major writer” because of his “talent.” There can be no major writers without original genius. Artists of genius, like Jackson Pollock, have painted things that have never been seen before… Take the case of James Joyce: people say he “wasted” his “talent” on the stream-of-consciousness style, when in fact he was simply born to originate it.

Kerouac adds:

Some geniuses come with heavy feet and march solemnly forward… Geniuses can be scintillating and geniuses can be somber, but it’s that unescapable sorrowful depth that shines through — originality…

Joyce was insulted all his life by practically all of Ireland and the world for being a genius. Some Celtic Twilight idiots even conceded he had some talent. What else were they going to say, since they were all going to start imitating him? But five thousand university-trained writers could put their hand to a day in June in Dublin in 1904, or one night’s dreams, and never do with it what Joyce did with it: he was simply born to do it.

…

When the question is therefore asked, “Are writers born or made?” one should first ask, “Do you mean writers of talent or writers of originality?” Because everybody can write but not everybody invents new forms of writing. Gertrude Stein invented new forms of writing and her imitators are just “talents.”

Who judges?

The criterion for judging talent or genius is ephemeral, speaking rationally in this world of graphs, but one gets the feeling definitely when a writer of genius amazes him by strokes of force never seen before and yet hauntingly familiar…

The main thing to remember is that talent imitates genius, because there’s nothing else to imitate. Since talent can’t originate, it has to imitate, or interpret…

Genius gives birth, talent delivers. What Rembrandt or Van Gogh saw in the night sky can never be seen again… Born writers of the future are amazed already at what they’re seeing now, what we’ll all see in time for the first time, and see many times imitated by made writers.

And with a nod to Sy Oliver and James Young’s tune “Tain’t What You Do (It’s The Way That Cha Do It)”:

Oftentimes the originator of new language forms is called “pretentious” by jealous talents. But it ain’t whatcha write, it’s the way atcha write it.

And that’s what get results…

After all “all art constantly aspires to the condition of music”:

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.