GEORGE Romero’s impressive movie-making career stretches back to the Pittsburgh area in the late 1960s and spans over forty years.

Like many horror filmmakers of his generation, Romero has seen his share of big successes, like Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Creepshow (1982), critical darlings like Martin (1976), cult classics such as The Crazies (1973) and the occasional out-right bomb, like Diary of the Dead (2007).

But several of Romero’s finer films didn’t meet with financial or critical success, and deserve to have further light shone on them. Accordingly, my selections for the most underrated of his feature films are listed below.

Hungry Wives (1971)

George Romero’s self-described “feminist” horror movie, also known as Jack’s Wife and Season of the Witch, involves a bored suburban house-wife, Joan Mitchell (Jan White) who is only able to define herself in terms of her place in the suburbs as a married woman and a home-maker.

In an attempt to rebel against her “accepted” role in society, Joan delves into witchcraft and then adultery, but the movie’s crafty point is, commendably, that witchcraft is no more defining or self-actualizing for Joan than being a house-wife had been. She has merely changed her demographic affiliation or club, while everything else in her life remains the same

Hungry Wives is so powerfully-wrought because George Romero serves as both editor and director, and his editing flights-of-fancy make the movie’s point plain in terms of visualizations. Early on, for instance, Joan experiences a telling dream in which her husband leads her around on a leash, like a dog. One of the film’s final images reveals Joan involved in a coven ritual, a red rope looped about her neck, and the symbolism is plain: she has merely traded one trap for another. This visual counterpoint is underlined by the counsel of Joan’s therapist, who advises her that she is imprisoning herself, and must change that pattern if she hopes to make her life better.

Day of the Dead (1985)

Before 2007 at least, Day of the Dead (1985) was the least-appreciated of the famous Romero living Dead cycle. This lack of approbation was a result, in part,of the film’s overtly and relentlessly serious tone. For all its mayhem and violence, Dawn of the Dead — set at a shopping mall — also had a fun or jaunty side to it. But Day of the Dead proved a totally different animal: a solemn and extremely gory exploration of mankind’s last chapter as the dominant species on Earth.

Rather unconventionally, the movie ends with a committed and likable protagonist, Sarah (Lori Cardille) realizing it is all over but the crying, and essentially giving up the fight so as to live her last years (and the last years of humanity…) on a nice island beach somewhere with two decadent helicopter pilots.

But importantly, Day of the Dead also moves the cycle forward in significant fashion via its introduction of Bub (Howard Sherman), a zombie who has been domesticated, after a fashion, and reveals both rudimentary memory, and rudimentary humanity.

In fact, this lovable zombie shows more humanity than the film’s brutal military leader, Rhodes (Joe Pilato), and thereby suggests that the change in the social order might not be all that bad, if the zombies continue to evolve towards something…civilized.

Finally, Day of the Dead features an epic and awe-inspiring opening,:a view of a city in Florida completely overrun by the living dead. This moment is arguably the biggest in scope of the entire dead run, and establishes brilliantly the zombies’ numerical advantage. As this shot reveals, Day of the Dead is actually the Twilight of Man.

Monkey Shines (1988)

I still remember discussing this Romero horror film at length with visiting movie critic Molly Haskell at the University of Richmond in the late 1980s. We agreed that the critical community had virtually ignored what was a very powerful and very relevant film about human nature.

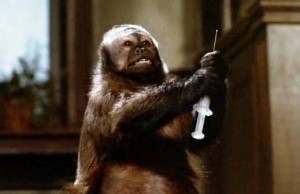

Monkey Shines involves a man, Allan (Jason Beghe) who is paralyzed in an accident and becomes a quadriplegic. As such, he is provided by his scientist friend (John Pankow) a capuchin monkey named Ella to act as his arms and legs. Before long, Ella and Allan form a close bond of friendship and dependence…but then each begins acting on each other’s emotional states and desires. Soon bloody murder is being committed…but is it at Ellas behest, or Allan’s?

Monkey Shines informs audiences that the “devil” is “animal instinct,” which acts by its “own set of laws,” and then asks the pertinent question: are we that different from the lower animals we treat as pets? Are we truly evolved, or — underneath the surface — are we just as violent and capricious as cousins in the jungle?

The scenes involving Ella in Monkey Shines are convincing and powerful, save for a few moments where an inert stand-in is clearly utilized, and the film’s debate about instinct (an avatar for the human subconscious in some critical way…) makes the film stand out in an era when rubber reality and slasher movies reigned supreme.

The Dark Half (1993)

Here’s a Stephen King adaptation that almost nobody loves, or even remembers. In The Dark Half (1993) Timothy Hutton plays Thad Beaumont, a writer grappling with his famous nom du plum, George Stark. When Beaumont elects to kill his famous literary name, however, the alter ego comes to life and threatens the writer and his entire family.

A deliberate and modernJekyll-Hyde story, The Dark Half is part of an early 1990s “meta” or post-modern movement in horror. Films such as Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) and John Carpenter’s In The Mouth of Madness (1994) gazed at worlds in which the line between fiction and reality were blurred. The Dark Half treads meaningfully in similar territory, and gazes at the act of writing as literally a physical birth, as an independent creation that – much like a human child – can no longer be fully controlled by its creator.

There’s nothing flashy or expensive about The Dark Half, and the ending is a bit of a bust, but otherwise Romero crafts a thoughtful, low-key horror film that possesses some electric jolts. One early scene, set in an operating room is downright terrifying, and another — with a woman broaching an invader in her dark apartment — also gets the blood flowing.

More than anything, however, The Dark Half explores the idea that the creative act of writing represents a violent assertion of will. “The only way to do it is to do it,” one character notes, and this same determination indeed is what wills the Dark George Stark into the world.

Survival of the Dead (2009)

Survival of the Dead is yet another Romero living dead movie, and another seriously underrated work of art. Since the very beginning of his career in 1968, director Romero has used his zombie saga to explore political and social issues of the time.

For example, Night of the Living Dead speaks to the political violence and upheaval of 1968, and to race relations in America. Dawn of the Dead very much concerns conspicuous consumption and the “Crisis in Confidence” Carter Age. And Land of the Dead (2005) explores post 9/11 territory.

Similarly, Survival of the Dead is a thoughtful, point-for-point allegory for American involvement in the Iraq War. Unfortunately, horror movie fans were too busy complaining about CGI blood effects to notice the movie’s clever thematic framework.

In short, Survival of the Dead involves a refugee, O’Flynn (Kenneth Welsh) — the fictional equivalent of Ahmed Chalabi — who tricks American armed forces into fighting his war for him, and ousting his enemy, Muldoon (Richard Fitzpatrick) — a Saddam Hussein figure – from the land that he would like to lead, paradise-like Plum Island.

Obligingly the National Guard moves in — guns blazing — only to find that matters aren’t so straight-forward. The soldiers have become involved in a pissing match that, ultimately, doesn’t concern them or their well-being.

The film features an Old West sort of milieu on Plum Island, with rivals O’Flynn and Muldoon (Richard Fitzpatrick) wearing cowboy hats and riding horses while zombies (here called Dead-Heads) are trapped in the nearby corral.

Again, Romero’s thoughtful set-up makes it impossible not to think of the post-911 “dead or alive” rhetoric from the Bush White House. The film’s final imagery — which depicts cowboy zombie versions of O’Flynn and Muldoon trying to kill each other under a bright moon — makes one despair that human nature is ever going to change.

With neo-con dead-enders everywhere on cable news stations this week attempting to re-enlist America in the war in Iraq a decade later, Survival of the Dead is more relevant than ever. Accordingly, this Romero film is really about discredited zombie ideologies that have long outlived their usefulness, but which keep coming back from the dead to threaten the rest of us.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.