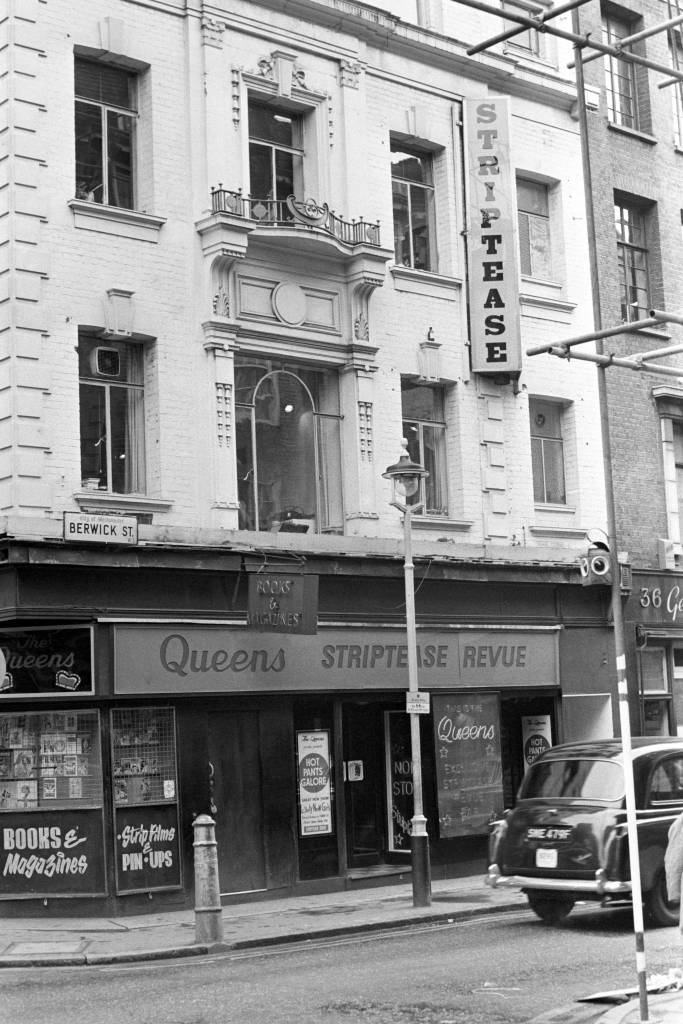

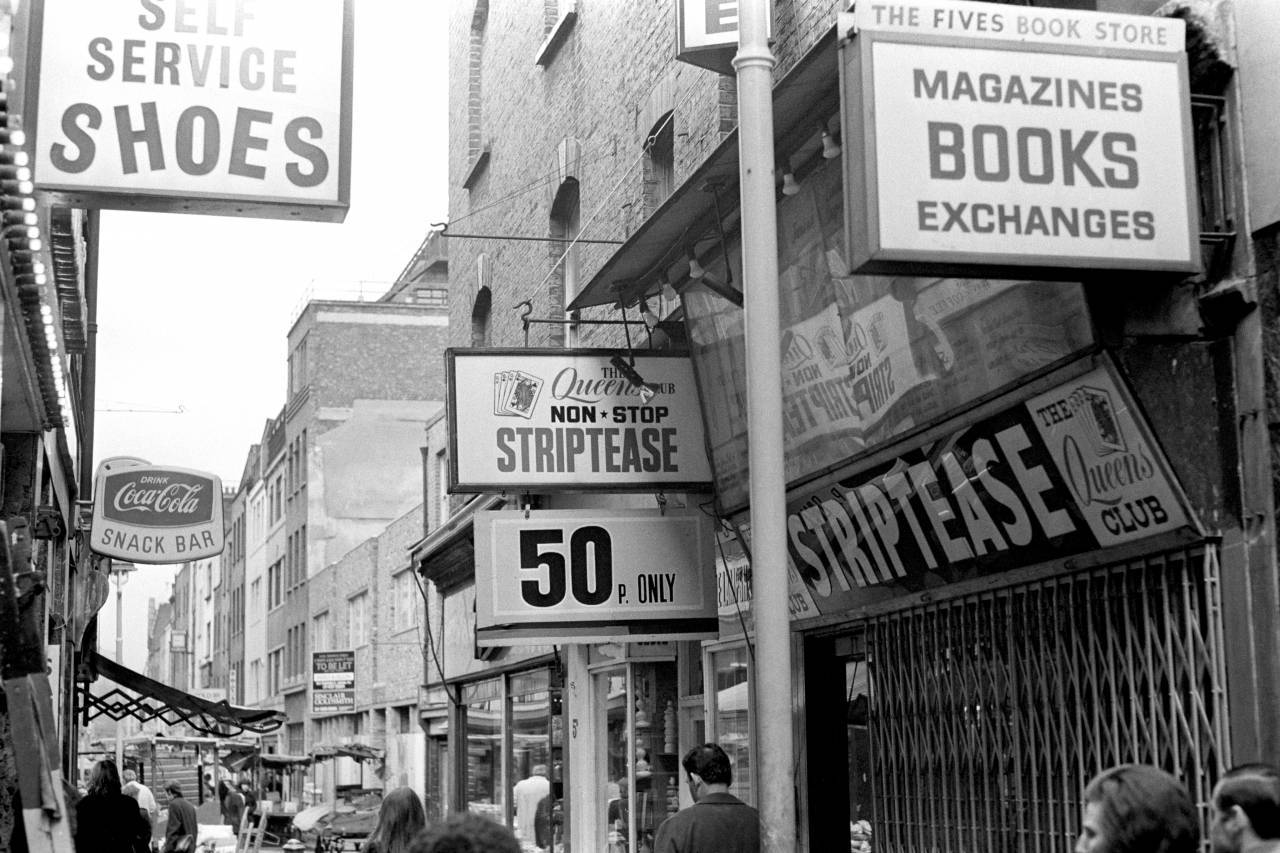

For over 200 years Soho has had a racy reputation. Prostitution, for instance, was relatively open in the area at least until the Street Offences Act of 1959. The number of sex-shops, however, had always been relatively few but rose from just a handful in the early sixties to almost sixty by 1970.

Suddenly it seemed the dirty book-shops were almost taking over the area. There was corruption in Soho – essentially collusion between the ‘pornographers’ and the police – and it was an open secret amongst journalists, lawyers and the police themselves. Although almost no one vaguely knew the extent of it.

While the Soho porn industry was steadily proliferating there was an almost ferocious police assault against, what they called, politically subversive obscenity and apologists for the alternative society.

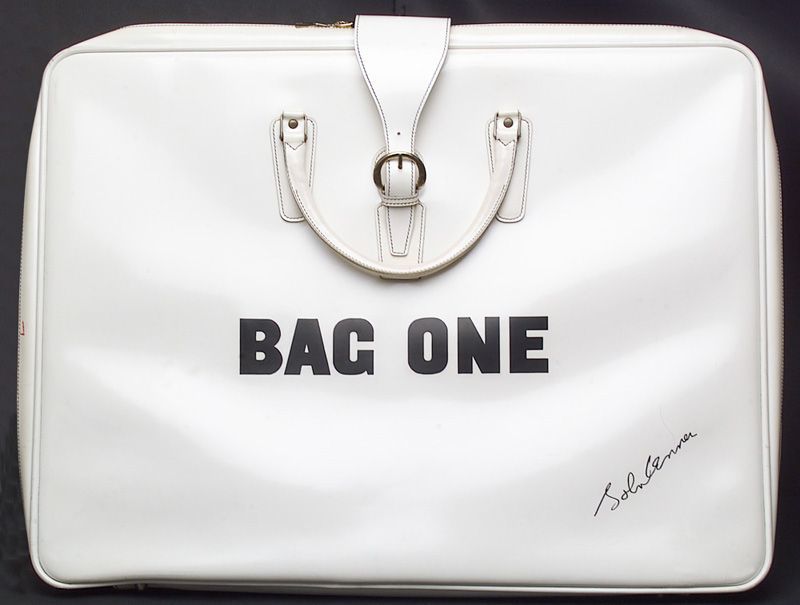

In 1970 Eugene Schuster’s London Arts Gallery on New Bond Street in salubrious Mayfair was raided by the Obscene Publications Squad, known to many at the time as the infamous ‘Dirty Squad’. The gallery was immediately closed down and Schuster was charged under the Obscene Publications Act. A situation not abnormal for the time perhaps but this particular closure garnered an extraordinary amount of publicity.

It had only been open for two days but the gallery had been showing The Bag One exhibition – fourteen ‘intimate and erotic’ lithographs by John Lennon that depicted himself and his wife, Yoko Ono, in various sexual poses. Each lithograph was for sale for £40 each or £550 for the set which included an extremely handy leather hold-all to keep them in.

John Lennon lithograph of Yoko shown at the Bag One exhibition at the London Arts Gallery in Mayfair.

Soon after the forced closure of the gallery the Director of Public Prosecutions received a letter from a member of the public, a Mr P.F.C. Fuller esq. The missive warned that if the court case went ahead there was a chance other art collections throughout the country could potentially be in trouble. Including, he suggested, even the Queen’s. Fuller wrote:

“I understand that HM the Queen has some highly erotic work by Fragonard.”

The DPP, presumably, decided that the Queen’s art collection was not at risk from the Dirty Squad and the case went to court several months later in April 1970. The summons, using a law that was 160 years old, alleged that the gallery had “exhibited to public view eight indecent prints to the annoyance of passengers, contrary to Section 54(12) of the Metropolitan Police Act, 1839″. It was an odd law and the warrant had originally been issued under the Obscene Publications Act, but at a later date it was decided to proceed under the Act of 1839 which meant that the defence of artistic merit or public interest could not be used. The defence concentrated on the word ‘annoyance’ arguing that it was an integral part of the offence and Detective-Inspector Patrick Luff, of New Scotland Yard told the magistrate that when he went to the gallery on January 15 about forty people were viewing the prints: “I saw no display of annoyance from the younger age group, but one gentleman was clearly annoyed.”

Mr. St. John Harmsworth, the magistrate, asked the Detective-Inspector: “Did he stamp his foot?” To which Luff replied, “anger was registered on his face.”

The Guardian reported that a prosecution witness, a grey-haired accountant from Wandsworth Common had “felt a bit sick that a man should draw himself and his wife in such positions.” It had been a shock, he said, to see a picture of “Yoko in the nude with rather exaggerated bosom with apparently somebody sucking a nipple.”

Amidst much laughter in court the case was dismissed with the magistrate deciding that anyway there are no passengers in a gallery – “they have, for the time being, finished passaging” and thus Lennon’s prints were “unlikely to deprave or corrupt.”

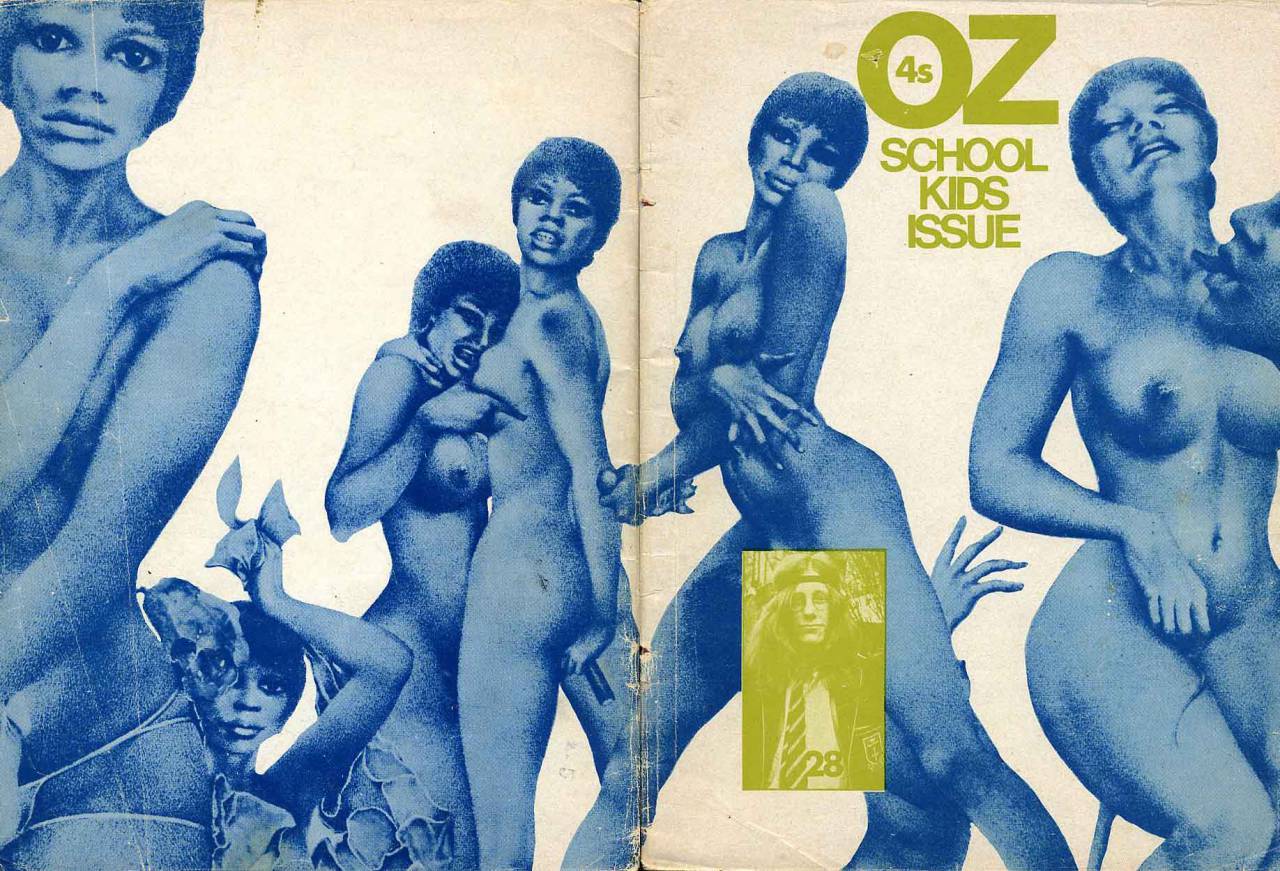

The following month in May 1970, in response to accusations the magazine was losing touch with younger readers, OZ magazine published the ‘SCHOOL KIDS ISSUE’, OZ No. 28. The issue was so-called not because it was aimed at children but was written by around 20 secondary school students who had answered an advert in OZ No. 26:

Some of us are feeling old and boring. We invite our readers who are under 18 to come and edit the April issue. We will choose one person, several or accept collective applications from a group of friends. Oz belongs to you.

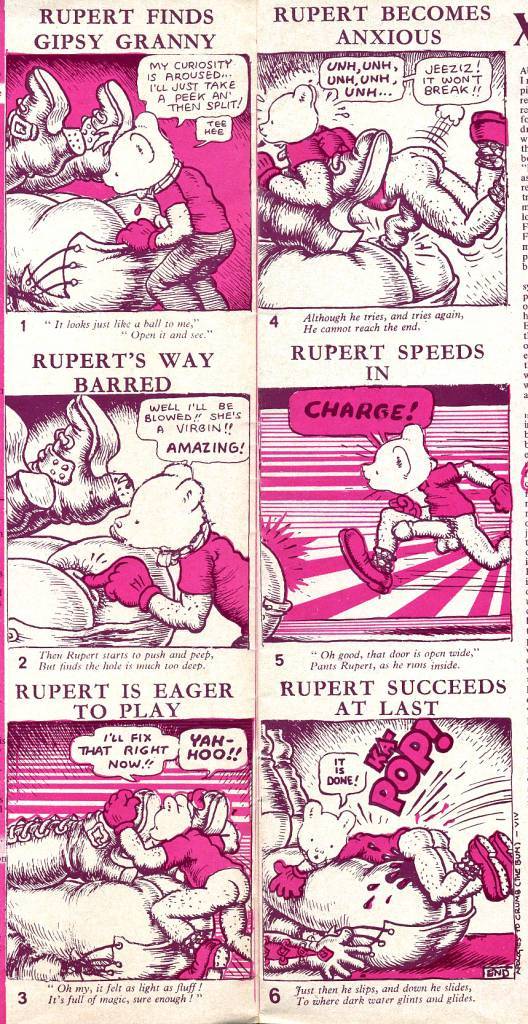

The young would be journalists, which included the music writer Charles Shaar Murray and Deyan Sudjic (now Director of the Design Museum), gathered at Richard Neville’s flat in Palace Gardens Terrace, by London’s Notting Hill Gate. Over a few weekends the magazine took shape. The finished issue (cover price: 48p) featured such treats as a racy Rupert Bear parody produced by 15-year-old Islington schoolboy Vivian Berger (his mother was Grace Berger, at the time Chair of the National Council for Civil Liberties), Jail Bait of the Month and a Review of Theodore Roszak’s The Making of a Counter Culture.

Vivian Berger had pasted the head of Alfred Bestall’s much loved Rupert the Bear onto an x-rated cartoon by cartoonist Robert Crumb.

Oz had been pushing boundaries, but the introduction of children was the trigger for the police to attack. As Jonathon Green notes in All Dressed Up: “The Establishment did not like Oz or the counter-culture that it represented – when Neville naively, injudiciously, combined ‘children’ with the usual irritants of drugs and sex and rock, they saw their chance.”

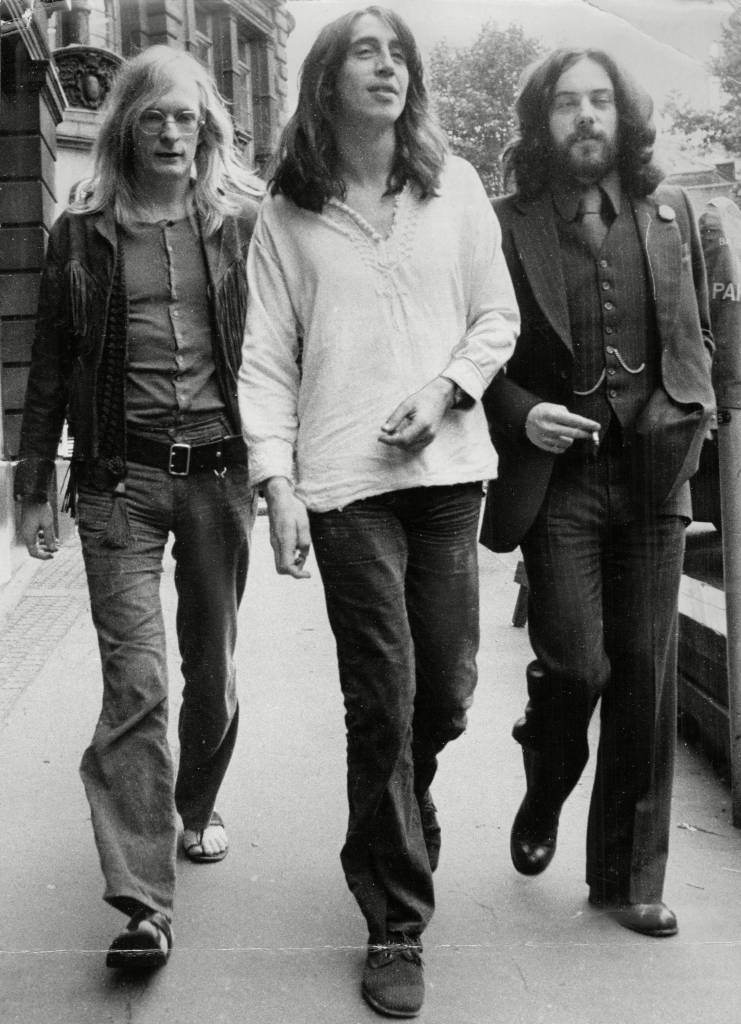

The magazine was raided by the Obscene Publications Squad in July 1970 seizing the filing cabinets and even the pictures from the walls. The three Oz editors – Richard Neville, co-founder of Oz in Sydney in 1963, Jim Anderson (‘the first out gay person I had ever met’ – Shaar Murray would later write) and “freak with a briefcase” 25 year old Felix Dennis who had previously worked as a gravedigger for Pinner County Council but was now the magazine’s business manager – were charged with producing a magazine which would “debauch and corrupt the morals of children and other young persons within the realm and to arouse and implant in the minds of those young people lustful and perverted desires”. The language seemed old fashioned and indeed it was – the charge hadn’t been used for 130 years but was intended as a way of avoiding the ‘public good’ defence that had saved Lady Chatterley seven years before. Felix Dennis, Richard Neville and Jim Anderson stood trial the following year in 1971.

It seemed odd to many that the notorious ‘Dirty Squad’ seemed happy to ignore the steady proliferation of sleazy Soho sex shops while continuing to seek prosecutions against hippie magazines such as Oz, the Little Red Schoolbook and International Times. When they raided and closed down the John Lennon exhibition on New Bond Street a few hundred metres away in Soho hardcore pornography was more or less openly on sale.

Geoffrey Robertson, then a fresh-faced Sydney law graduate and an Australian Rhodes Scholar, offered to help with the defence, and after several rebuttals by QCs worried about the effect the trial may have on their careers, John Mortimer, at the eleventh hour, agreed to defend the magazine. “Goody, goody – when do we start,” he told Neville and Robertson over their first meeting at lunch in a restaurant called Jonah’s. Neville had already met Mortimer several times and once described a party where Mortimer had mingled at a buffet with his girlfriend Louise Ferrier: “As he chatted about the bizarre sexual proclivities of Melbourne, it took a while for Louise to realise that his subject matter was the victorian Prime Minister, not the capital of Victoria.” Neville had also met at a dinner given by his sister Jill – a publisher in London. Later that night she had been woken at home by a phone call. “Hello, lovely,” whispered the notable QC already famous for his play A Voyage with my Father and for defending the publishers of Last Exit to Brooklyn, “as I’m in the area – I thought I might drop by and pop into bed?” It was an offer she immediately rebutted. Although it apparently caused no hard feelings, as he added, “I quite understand my dear, perhaps another time?”

Oz Magazine Editors James Anderson Richard Neville And Felix Dennis

Photo by Ronald Spencer / Associated Newspapers / Rex Features

The Oz trial was held in number 2 court at the Old Bailey and in front of Judge Michael Argyle who from the outset seemed to think Oz magazine threatened the fate of western civilisation. It eventually became the longest obscenity trial in history although the prosecution case was actually rather brief and to the point with the only exhibit being the Schoolkids Oz magazine itself. Geoffrey Robertson in The Justice Game recalled when Detective Inspector was giving evidence, “he told the court that his interview with Felix Dennis had ended with the suspect exclaiming “Right on!” Judge Argyle, taking down the evidence longhand, looked up, puzzled. “Write on… but you had finished the interview?” “Not write on – W-R-I-T-E, my Lord – but R-I-G-H-T on.” It’s a revolutionary expression,” Luff said helpfully.

The defence took much longer with a myriad of witnesses brought in to explain why the magazine was not obscene. George Melly, the jazz singer and film critic at one point was questioned by the prosecutor Brian Leary: “If you really believe more openness is better, what do you think is wrong with an advertisement that describes oral sex attractively?”

Melly replied “Nothing. I don’t think cunnilingus could do actual harm…”

A confused Judge Argyle interrupted to ask, “For those of us who don’t have a classical education what do you mean by this word “cunnilinctus”?’ (Geoffrey Robertson later wondered whether the judge thought it was some kind of cough medicine). Melly apologised, “I’m sorry my Lord I’ve been inhibited by the architecture. I will try and use better known expressions in the future: Sucking. Blowing. Or going down or gobbling. Or, as we said in my naval days, ‘yodelling in the canyon’. Twenty-six years later Kenny MacDonald, who either knew the odd sailor or was a keen student of the Oz obscenity trial, wrote the runner-up song to represent the UK in the Eurovision song contest in 1997 called Yodel in the Canyon of Love sung by Do-Re-Mi featuring Kerry.

It was obvious to anyone at the trial that Judge Argyle wanted no other outcome other than that the defendants were to be convicted. His contemptuous and biased summing-up at the end of the Oz trial has now gone down in legal history some have said that he misdirected the jury an extraordinary 78 times.

At one point, after the jury had retired to consider their verdict, they asked Judge Argyle if he could help determine the exact meaning of ‘indecency’. Argyle answered: “If a woman takes her clothes off on a crowded beach, we think that is indecent in this country.” After a total of four hours and armed with this helpful explanation, the jury of nine men and three women found all three defendants guilty.

“Send them down!” ordered Argyle, happy with the fact that he had saved the fabric of western civilisation.

The three Oz editors were taken to prison and had their heads shaved. In the early seventies long-hair was still seen as particularly anti-establisment and the shaving was an act that intended to (and indeed did) cause a greater stir than the already considerable outcry surrounding the trial and verdict.

At the sentencing, a week later, the judge announced to a shorn Richard Neville, “I have no alternative but to sentence you to fifteen months’ imprisonment.” Incidentally Dennis was given a lesser sentence because Justice Argyle, considered the future publishing magnate and billionaire “very much less intelligent” than the other two defendants.

As they were taken downstairs another prisoner told Neville, “Christ. That’s what I got. And I tried to murder my wife.” While the sergeant who took them away quipped, “You can find more porn in Soho than what’s in the pages of Oz.”

It was alleged by Geoffrey Robertson that at the appeal the lord chief justice, Lord Widgery, sent his clerk, a former merchant seaman, to Soho one lunchtime to buy £20 worth of the hardest porn he could find. The contents of Oz “paled in comparison”.

Had the police not noticed the porn amidst the samizdat?

Off To Prison By Bus.. Left To Right Felix Dennis Richard Neville And James Anderson. The Three Editors Of Oz Magazine Were Jailed For Publishing An Obscene Article. Photo by Ronald Fortune / Associated Newspapers / Rex Features (1302418a)

3rd November 1971: James Anderson, Richard Neville, along with Felix Dennis arrive at the Old Bailey in London for their appeal against a conviction under the Obscene Publications Act with regard to an issue of their underground magazine ‘Oz’. As a gesture of defiance, the three are wearing wigs to cover the ‘prison’ haircuts, which were given to them whilst in Wormwood Scrubs. (Photo by Dennis Oulds/Central Press/Getty Images)

The Conservative Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, hauled in Detective Chief Inspector George Fenwick, at the time in charge of the Obscene Publications Squad. He explained why he’d gone after Oz and the Little Red Schoolbook. “In this country at the minute there are somewhere in the region of 80 publications which advocate what in the current idiom is called the alternative society,” said Fenwick. “Of these about 25 can be termed ‘underground’ press and a number of them contain articles which can be described as indecent. However, by far the worst of these are Oz, Frendz and IT, in that order. These in fact are the only ones against whom action has been taken or indeed contemplated in the last 12 months.”

This was all very well but Maudling asked the senior policeman exactly why the porn barons in Soho, at the same time, seemed to be operating with somewhere close to impunity. Fenwick answered: “It is an unfortunate fact of life that pornography has existed for centuries and it is unlikely that it can ever be stamped out.”

Maudling was shocked with what was rather a lame excuse, and he quickly initiated a major corruption inquiry into the Metropolitan police. The Government and the judiciary, albeit rather slowly, were coming to the conclusion that there was more than the odd bad apple within the ranks of London’s finest.

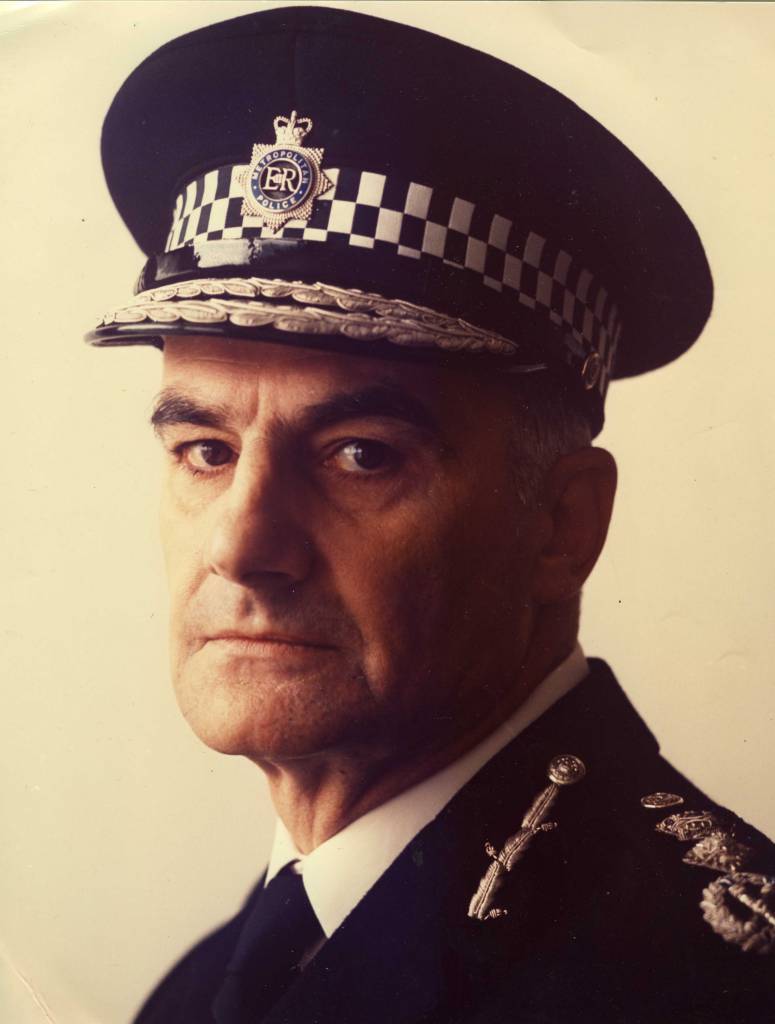

In 1972 Maudling appointed Robert Mark to be the new Commissioner of the Metropolitan police. To the old guard in the Met he was a provincial outsider. Mark had a reputation as ‘Mr Clean’ and the Met had nicknames for him such as the particularly witty ‘The Manchester Martinet’ and the hilarious ‘The Lone Ranger from Leicester’.

In Soho by now it was impossible not to notice the porn shops and unusually for shops in Britain in the mid-seventies they were open seven days a week. The windows were filled with garish displays of soft-core magazines and books but with notices implying, usually correctly, that there was a wider range of harder material to be found inside.

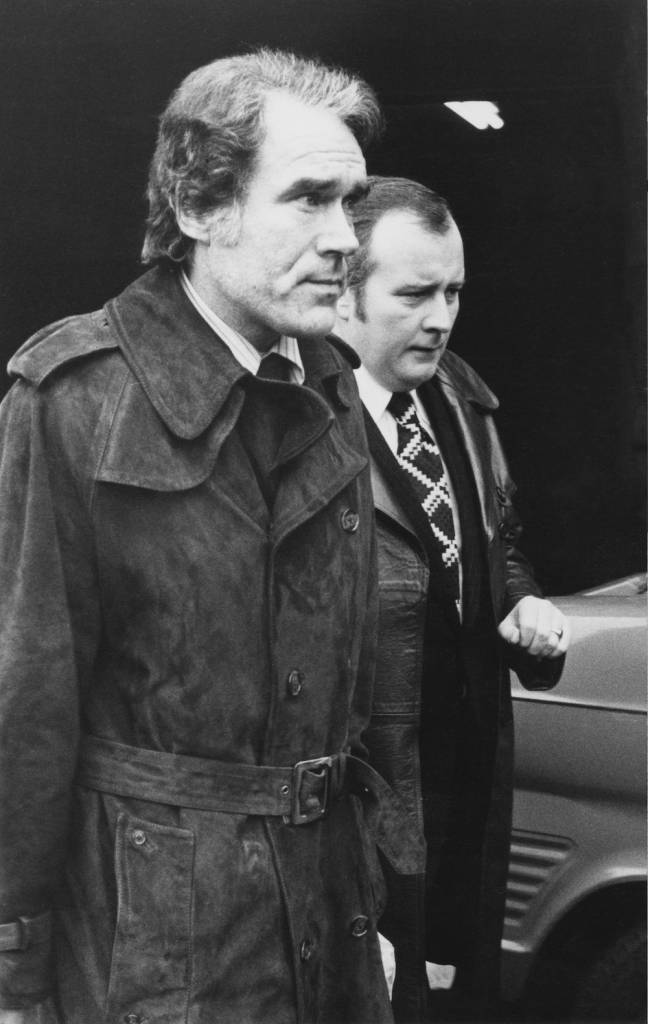

Soho sex club owner Jimmy Humphreys arrives at Heathrow Airport, handcuffed to Detective Sergeant Terence Brown of Scotland Yard (right), 10th January 1974. Humphreys was arrested in Amsterdam and brought back to England to testify against several police officers charged with corruption.

In the same year as Mark’s appointment various Sunday tabloids exposed a connection between James Humphreys (who openly ran two strip clubs and was one of the biggest operators of pornographic bookshops in Soho) and Commander Kenneth Drury. They had both enjoyed a luxurious two week holiday in Cyprus accompanied by their wives, all paid for, of course, by the Soho pornographer.

Drury was hopelessly compromised and concocted a yarn that he was in Cyprus looking for the train robber Ronnie Biggs and contradictorily paid for the trip himself. Nobody believed the story.

Humphreys quickly realised the danger for him of appearing to his criminal associates as a police informant and announced that Drury had set up the whole thing. After a police raid at his house a diary of Humphrey’s was found in a wall-safe and open-mouthed the corruption investigators found that it unbelievably detailed payments to seventeen different policemen including Drury.

Kenneth Drury, the former head of the Flying Squad, who appeared at Bow Street Magistrates court. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Even senior policemen such as Bill Moody – Head of the Obscene Publications Squad and, incredibly, his superior Commander ‘Wally’ Virgo – a man who had overall control of nine squads including the Flying, Drugs and the Porn Squad were being paid off.

It was estimated that James Humphreys and his fellow porn barons were paying an extraordinary £100,000 a year to corrupt policemen enabling them to continue selling porn unimpeded. Indeed it came to light that Humphreys had been so worried that Drury’s expensive lifestyle would give everything away, he had supplied him with expensive slimming drugs and a rowing machine to keep his weight down.

It came to light that it became important for the Dirty Squad to raid exhibitions such as John Lennon’s Bag One and bust ‘alternative’ magazines such as Oz and Little Red Schoolbook to at least look like they were doing something.

The corrupt policeman had built a delicately balanced house of cards that soon came tumbling down. Initially there were just the usual discrete early retirements and resignations but eventually there were two major corruption trials and George Fenwick, Bill Moody, Wally Virgo and Kenneth Drury were all given between ten and fourteen years in prison in 1977. Mr Justice Mars Jones after Fenwick’s trial said:

“Thank goodness the Obscene Publications Squad had gone. I fear the damage you have done may be with us for a long time.”

After the second trial Mars-Jones said it revealed “corruption on a scale which beggars description”.

The Home Office, in response to the corruption, and in conjunction with the Met Police Commissioner Sir Robert Mark, appointed the Assistant Chief Constable of Dorset Constabulary, Leonard Burt to investigate all the allegations.

In August 1978 a team of two hundred officers began investigating the Metropolitan police from top to bottom. Referring to Burt’s Dorset roots it had the nickname Operation Countryman. At first the team were housed at Camberwell Police Station but following clumsy attempts to interfere with their documents, records and evidence they moved to Godalming Police Station in Surrey.

After six years, Operation Countryman presented its findings to the Home Office and the Commissioner. Eventually over 400 police officers lost their jobs during or after the Countryman investigation. Despite the report recommending that 300 officers should face criminal charges, not one officer was ever charged with a criminal offence as a result of the investigation.

Plus ca change.

You can read the entire magazine here.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.