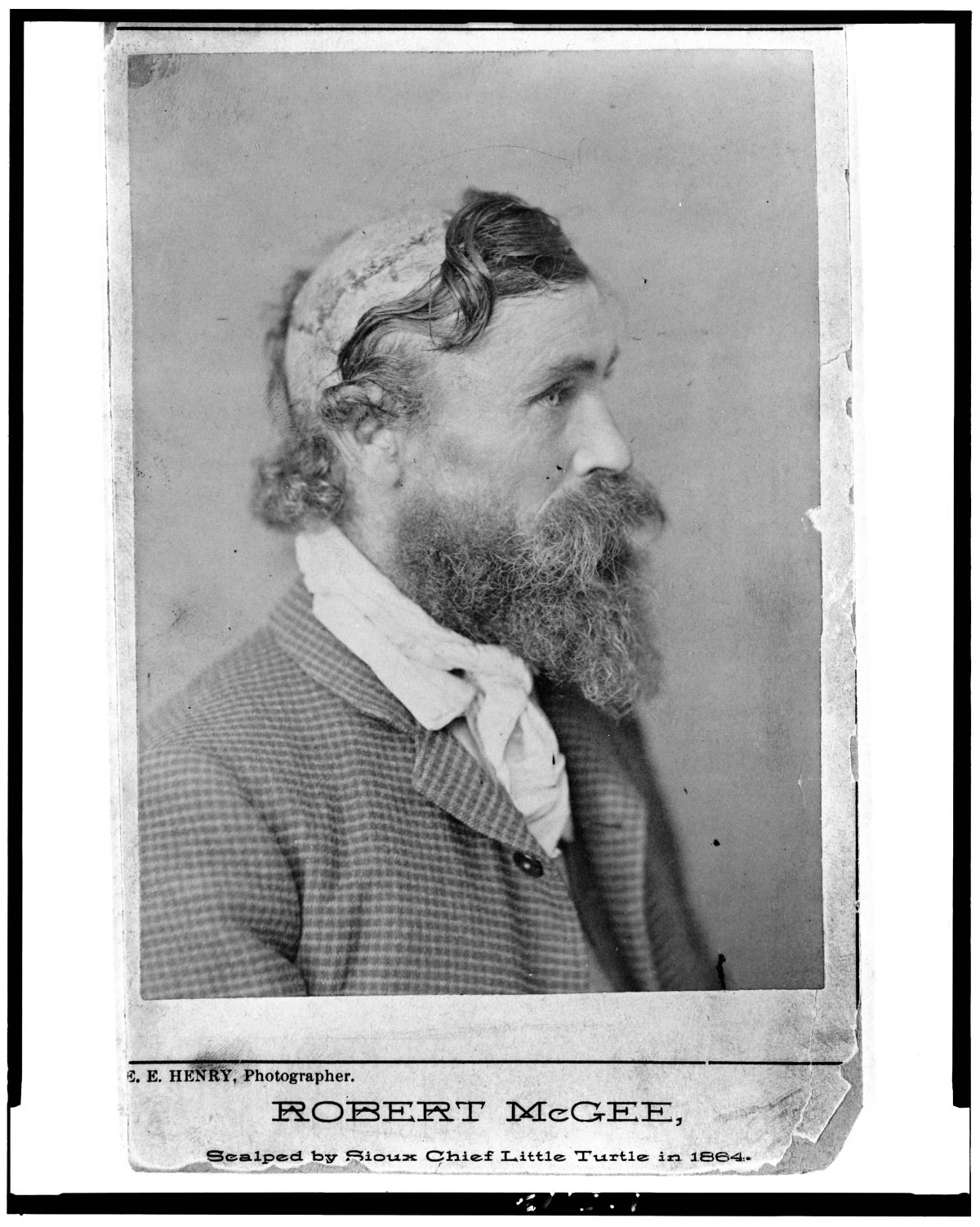

In the early years of the 20th Century, Robert McGee sat for photographer E.E. Henry (1826-1917). The picture, the portrait you see above, shows McGee after he was scalped in the summer of 1864.

Back then, the 14-year-old orphan had been recruited as a teamster with the H.C. Barret company to transport a caravan of flour to Fort Union in New Mexico Territory.

What happened to McGee is told in The Old Santa Fe Trail: The Story of a Great Highway by Colonel Henry Inman (1837-1899), a Late Assistant Quartermaster, United States Army, who became a journalist, writer and newspaper publisher. In Chapter 20, Inman tells us how Robert McGee came to be at Pawnee Rock, lose his scalp and live to tell the tale. Told by Inman, it is the stuff of Ripping Yarns. The language is very much of the period – and aimed squarely at a non Native American audience.

In 1893, the American Historical Association convened at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History”, in which he invited his audience to “stand at Cumberland Gap [the famous pass through the Appalachian Mountains], and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur trader and hunter, the cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.”

Inman’s text begins with a preface by the hymned W. F. Cody, “Buffalo Bill” (February 26, 1846 – January 10, 1917). As for context, in 1964: President Abraham Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant commander in chief of all Union armies; in the so-called ‘Indian Wars’, Colorado volunteers led by Colonel John Chivington massacre hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapahoe noncombatants at Sand Creek, Colorado; and Asa Mercer was “importing” women to the Pacific Northwest to balance the gender ratio.

That portion of the great central plains which radiates from Pawnee Rock, including the Big Bend of the Arkansas, thirteen miles distant, where that river makes a sudden sweep to the southeast, and the beautiful valley of the Walnut, in all its vast area of more than a million square acres, was from time immemorial a sort of debatable land, occupied by none of the Indian tribes, but claimed by all to hunt in; for it was a famous pasturage of the buffalo.

…

Pawnee Rock was a spot well calculated by nature to form, as it has done, an important rendezvous and ambuscade for the prowling savages of the prairies, and often afforded them, especially the once powerful and murderous Pawnees whose name it perpetuates, a pleasant little retreat or eyrie from which to watch the passing Santa Fe traders, and dash down upon them like hawks, to carry off their plunder and their scalps.

Through this once dangerous region, close to the silent Arkansas, and running under the very shadow of the rock, the Old Trail wound its course. Now, at this point, it is the actual road-bed of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, so strangely are the past and present transcontinental highways connected here.

Who, among bearded and grizzled old fellows like myself, has forgotten that most sensational of all the miserably executed illustrations in the geographies of fifty years ago, “The Santa Fe Traders attacked by Indians”? The picture located the scene of the fight at Pawnee Rock, which formed a sort of nondescript shadow in the background of a crudely drawn representation of the dangers of the Trail.

If this once giant sentinel of the plains might speak, what a story it could tell of the events that have happened on the beautiful prairie stretching out for miles at its feet!

…

Scalp-Shirts by Edward S. Curtis, Edward S – 1908

One of the most horrible massacres in the history of the Trail occurred at Little Cow Creek in the summer of 1864. In July of that year a government caravan, loaded with military stores for Fort Union in New Mexico, left Fort Leavenworth for the long and dangerous journey of more than seven hundred miles over the great plains, which that season were infested by Indians to a degree almost without precedent in the annals of freight traffic.

The train was owned by a Mr. H. C. Barret, a contractor with the quartermaster’s department; but he declined to take the chances of the trip unless the government would lease the outfit in its entirety, or give him an indemnifying bond as assurance against any loss. The chief quartermaster executed the bond as demanded, and Barret hired his teamsters for the hazardous journey; but he found it a difficult matter to induce men to go out that season.

Buffalo Bill ca. 1913

Among those whom he persuaded to enter his employ was a mere boy, named McGee, who came wandering into Leavenworth a few weeks before the train was ready to leave, seeking work of any description. His parents had died on their way to Kansas, and on his arrival at Westport Landing, the emigrant outfit that had extended to him shelter and protection in his utter loneliness was disbanded; so the youthful orphan was thrown on his own resources. At that time the Indians of the great plains, especially along the line of the Santa Fe Trail, were very hostile, and continually harassing the freight caravans and stage-coaches of the overland route. Companies of men were enlisting and being mustered into the United States service to go out after the savages, and young Robert McGee volunteered with hundreds of others for the dangerous duty. The government needed men badly, but McGee’s youth militated against him, and he was below the required stature; so he was rejected by the mustering officer.

Mr. Barret, in hunting for teamsters to drive his caravan, came across McGee, who, supposing that he was hiring as a government employee, accepted Mr. Barret’s offer.

By the last day of June the caravan was all ready, and on the morning of the next day, July 1, the wagons rolled out of the fort, escorted by a company of United States troops, from the volunteers referred to.

…

On the 18th of July, the caravan arrived in the vicinity of Fort Larned. There it was supposed that the proximity of that military post would be a sufficient guarantee from any attack of the savages; so the men of the train became careless, and as the day was excessively hot, they went into camp early in the afternoon, the escort remaining in bivouac about a mile in the rear of the train.

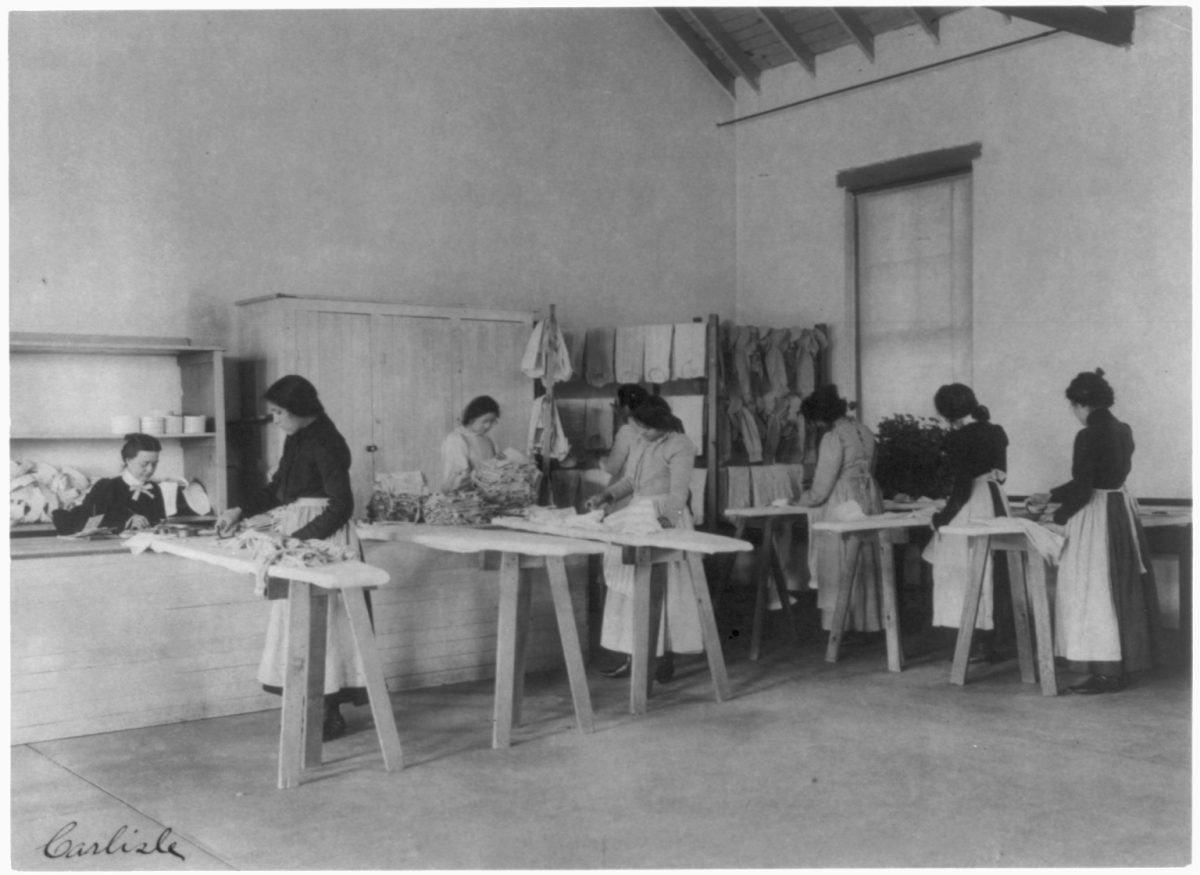

Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pa. Cooking class – 1901

About five o’clock, a hundred and fifty painted savages, under the command of Little Turtle of the Brule Sioux, swooped down on the unsuspecting caravan while the men were enjoying their evening meal. Not a moment was given them to rally to the defence of their lives, and of all belonging to the outfit, with the exception of one boy, not a soul came out alive.

The teamsters were every one of them shot dead and their bodies horribly mutilated. After their successful raid, the savages destroyed everything they found in the wagons, tearing the covers into shreds, throwing the flour on the trail, and winding up by burning everything that was combustible.

On the same day the commanding officer of Fort Larned had learned from some of his scouts that the Brule Sioux were on the war-path, and the chief of the scouts with a handful of soldiers was sent out to reconnoitre. They soon struck the trail of Little Turtle and followed it to the scene of the massacre on Cow Creek, arriving there only two hours after the savages had finished their devilish work. Dead men were lying about in the short buffalo-grass which had been stained and matted by their flowing blood, and the agonized posture of their bodies told far more forcibly than any language the tortures which had come before a welcome death. All had been scalped; all had been mutilated in that nameless manner which seems to delight the brutal instincts of the North American savage.

“Dreaming of Past Forays – Pretty Hawk, an aged Chief of the Sioux, N.D. Ca. 1908”

Moving slowly from one to the other of the lifeless forms which still showed the agony of their death-throes, the chief of the scouts came across the bodies of two boys, both of whom had been scalped and shockingly wounded, besides being mutilated, yet, strange to say, both of them were alive. As tenderly as the men could lift them, they were conveyed at once back to Fort Larned and given in charge of the post surgeon. One of the boys died in a few hours after his arrival in the hospital, but the other, Robert McGee, slowly regained his strength, and came out of the ordeal in fairly good health.

The story of the massacre was related by young McGee, after he was able to talk, while in the hospital at the fort; for he had not lost consciousness during the suffering to which he was subjected by the savages.

He was compelled to witness the tortures inflicted on his wounded and captive companions, after which he was dragged into the presence of the chief, Little Turtle, who determined that he would kill the boy with his own hands. He shot him in the back with his own revolver, having first knocked him down with a lance handle. He then drove two arrows through the unfortunate boy’s body, fastening him to the ground, and stooping over his prostrate form ran his knife around his head, lifting sixty-four square inches of his scalp, trimming it off just behind his ears.

Believing him dead by that time, Little Turtle abandoned his victim; but the other savages, as they went by his supposed corpse, could not resist their infernal delight in blood, so they thrust their knives into him, and bored great holes in his body with their lances.

After the savages had done all that their devilish ingenuity could contrive, they exultingly rode away, yelling as they bore off the reeking scalps of their victims, and drove away the hundreds of mules they had captured.

When the tragedy was ended, the soldiers, who had from their vantage-ground witnessed the whole diabolical transaction, came up to the bloody camp by order of their commander, to learn whether the teamsters had driven away their assailants, and saw too late what their cowardice had allowed to take place. The officer in command of the escort was dismissed the service, as he could not give any satisfactory reason for not going to the rescue of the caravan he had been ordered to guard.

So the story goes…

American anthropologist and ethnographer Frances Densmore records the Blackfoot chief Mountain Chief in 1916 for the Bureau of American Ethnology. Library of Congress.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.