Near the end of the war in 1945, Jewish prisoners from the Bergen-Belsen death camp were being transported by rail to another camp when their German guards abandoned the train. The US Army happened upon the survivors. Two soldiers took photographs. And from those pictures, decades later something wonderful happened.

Friday, April 13th, 1945. The Moment of Liberation.

Farsleben, Germany. By U.S. Army, Major Clarence Benjamin, 743rd Tank Battalion.

Matthew Rozell is a United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Teacher Fellow and teaches history at his alma mater in upstate New York. His work has resulted in the reuniting of 275 Holocaust survivors with the American soldiers who freed them. How that came about is a story of curiosity, chance, the human spirit and the power of photography.

Matthew was interviewing World War II US Army tank commander Carrol Walsh in July 2001. ‘For two hours we talked about battles and close calls, friends he lost and those he bonded with,’ Matthew writes. ‘He hated the war, he hated the Army. “Well, I think you had an obligation and you knew it, and you weren’t going to let the guys down, that’s all,” said Walsh. He mentioned the train, almost as an afterthought, and only when prompted by his daughter.’

(George Gross and Red Walsh) “This is a picture of two comrades who depended upon each other in the war. I am the one on the viewer’s left; on the right is Judge Carrol S. Walsh, who was with me at the train and at most of our memorable experiences in combat.”

Carrol Walsh invited Matthew to contact his friend on the West coast, George C. Gross, who had a negative of the photo you see at the top of this story and ten others he’d taken of the train.

What happened next made the past come alive. Dr. Gross was happy to meet and talk. In March 2002, Sgt. Gross told Matthew his story. The captions to the images below are his words.

Dr Gross got to know quite a few of the people he helped save before he died on Feb. 1, 2009. Before we hear from him, some words about that train. In his book Move out Verify: the Combat Story of the 743rd Tank Battalion, Wayne Robinson tells us what the Americans saw:

A few miles northwest of Magdeburg there was a railroad siding in a wooded ravine not far from the Elbe River. Major Clarence Benjamin in a jeep was leading a small task force of two light tanks from Dog Company on a routine job of patrolling. The unit came upon some 200 shabby looking civilians by the side of the road. There was something immediately apparent about each one of these people, men and women, which arrested the attention. Each one of them was skeleton thin with starvation, a sickness in their faces and the way in which they stood-and there was something else. At the sight of Americans they began laughing in joy-if it could be called laughing. It was an outpouring of pure, near-hysterical relief.

The tankers soon found out why. The reason was found at the railroad siding.

There they came upon a long string of grimy, ancient boxcars standing silent on the tracks. In the banks by the tracks, as if to get some pitiful comfort from the thin April sun, a multitude of people of all shades of misery spread themselves in a sorry, despairing tableaux [sic]. As the American uniforms were sighted, a great stir went through this strange camp. Many rushed toward the Major’s jeep and the two light tanks.

Bit by bit, as the Major found some who spoke English, the story came out.

This had been-and was-a horror train. In these freight cars had been shipped 2500 people, jam-packed in like sardines, and they were people that had two things in common, one with the other: They were prisoners of the German State and they were Jews.

These 2500 wretched people, starved, beaten, ill, some dying, were political prisoners who had until a few days before been held at concentration camp near Hanover. When the Allied armies smashed through beyond the Rhine and began slicing into central Germany, the tragic 2500 had been loaded into old railroad cars-as many as 68 in one filthy boxcar-and brought in a torturous journey to this railroad siding by the Elbe. They were to be taken still deeper into Germany beyond the Elbe when German trainmen got into an argument about the route and the cars had been shunted onto the siding. Here the tide of the Ninth Army’s rush had found them.

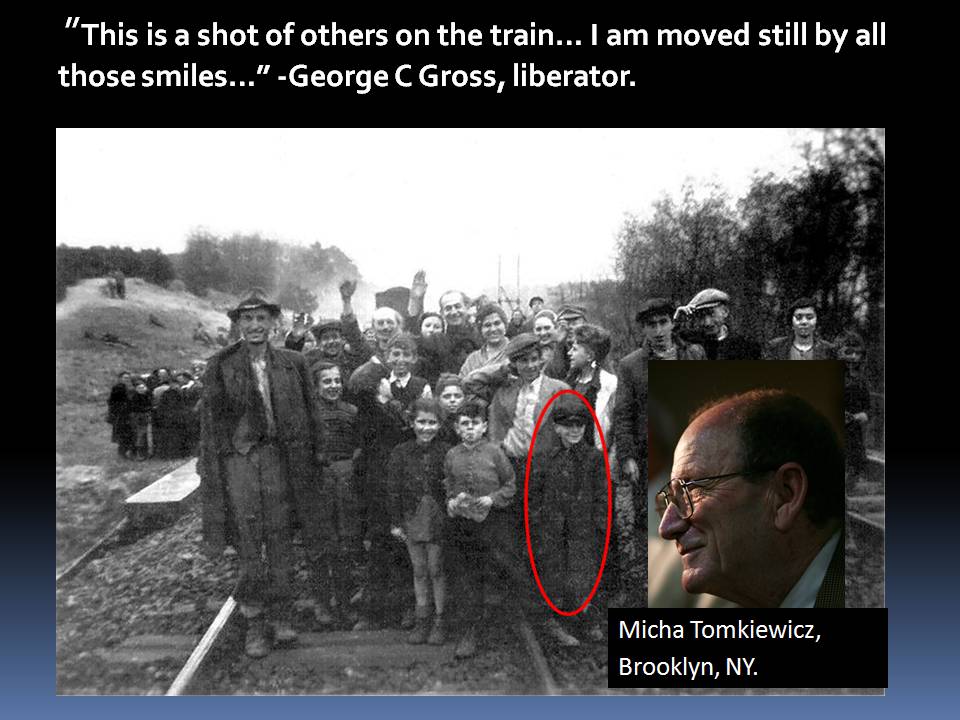

“This is a shot of others on the train. I am moved still by all those smiles, particularly the one on the thin little girl in front at the left.”

These are the words of George C. Gross – Spring Valley, California, June 3, 2001:

“On Friday, April 13, 1945, I was commanding a light tank in a column of the 743rd Tank Battalion and the 30th Infantry Division, moving south near the Elbe River toward Magdeburg, Germany. After three weeks of non-stop advancing with the 30th from the Rhine to the Elbe as we alternated spearhead and mop-up duties with the 2nd Armored Division, we were worn out and in a somber mood because, although we knew the fighting was at last almost over, a pall had been cast upon our victories by the news of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. I had no inkling of the further grim news that morning would bring.

“Suddenly, I was pulled out of the column, along with my buddy Sergeant Carrol Walsh in his light tank, to accompany Major Clarence L. Benjamin of the 743rd in a scouting foray to the east of our route. Major Benjamin had come upon some emaciated Finnish soldiers who had escaped from a train full of starving prisoners a short distance away. The major led our two tanks, each carrying several infantrymen from the 30th Infantry Division on its deck, down a narrow road until we came to a valley with a small train station at its head and a motley assemblage of passenger compartment cars and boxcars pulled onto a siding. There was a mass of people sitting or lying listlessly about, unaware as yet of our presence. There must have been guards, but they evidently ran away before or as we arrived, for I remember no firefight. Our taking of the train, therefore, was no great heroic action but a small police operation. The heroism that day was all with the prisoners on the train.

“Major Benjamin took a powerful picture just as a few of the people became aware that they had been rescued. It shows people in the background still lying about trying to soak up a bit of energy from the sun, while in the foreground a woman has her arms flung wide and a great look of surprise and joy on her face as she rushes toward us. In a moment, that woman found a pack left by a fleeing German soldier, rummaged through it, and held up triumphantly a tin of rations…

This view shows compartment cars. Most of the train was made up of boxcars. It looks as though one man at lower left is praying; others are sitting or lying on the ground.

“I pulled my tank up beside the small station house at the head of the train and kept it there as a sign that the train was under American protection now. Carroll Walsh’s tank was soon sent back to the battalion, and I do not remember how long the infantrymen stayed with us, though it was a comfort to have them for a while. My recollection is that my tank was alone for the afternoon and night of the 13th. A number of things happened fairly quickly. We were told that the commander of the 823rd Tank Destroyer battalion had ordered all the burgermeisters of nearby towns to prepare food and get it to the train promptly, and were assured that Military Government would take care of the refugees the following day. So we were left to hunker down and protect the starving people, commiserating with if not relieving their dire condition.

…

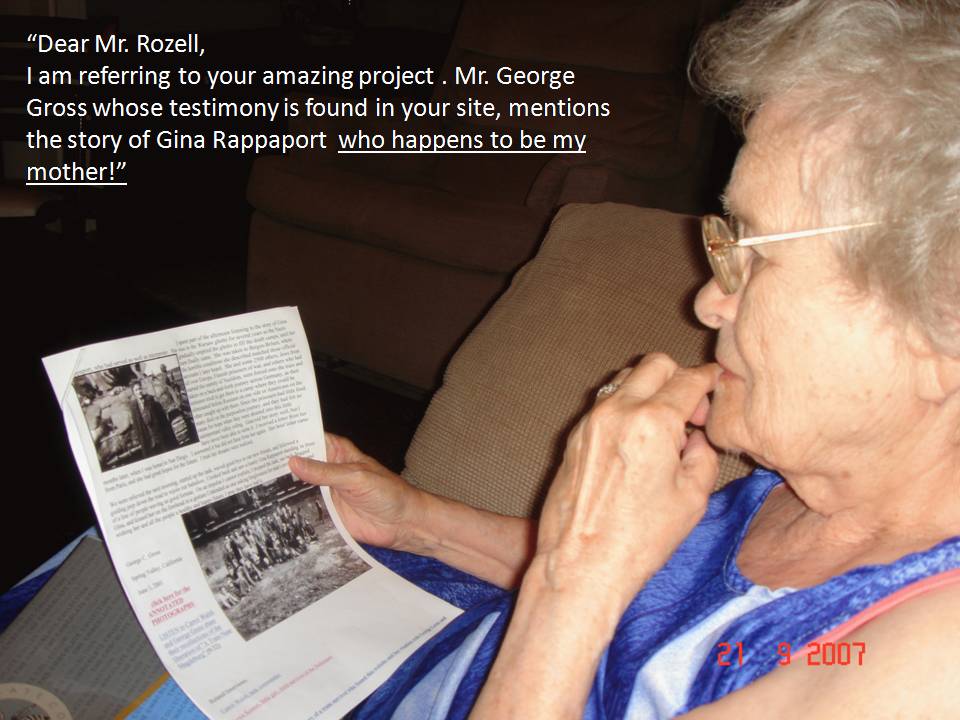

“A young woman named Gina Rappaport came up and offered to be my interpreter. She spoke English very well and was evidently conversant with several other languages besides her native Polish. We stood in front of the tank as along line of men, women, and little children formed itself spontaneously, with great dignity and no confusion, to greet us. It is a time I cannot forget, for it was terribly moving to see the courtesy with which they treated each other, and the importance they seemed to place on reasserting their individuality in some seemingly official way. Each would stand at a position of rigid attention, held with some difficulty, and introduce himself or herself by what grew to be a sort of formula: the full name, followed by “a Polish Jew from Hungary” – or a similar phrase which gave both the origin and the home from which the person had been seized. Then each would shake hands in a solemn and dignified assertion of individual worth. Battle-hardened veterans learn to contain their emotions, but it was difficult then, and I cry now to think about it. What stamina and regenerative spirit those brave people showed!”

Gina Rappaport – Friday, April 13th, 1945. This is Gina Rappaport, who spoke very good English and spent a couple hours telling me her story. I have notes packed away somewhere but have never felt up to trying to make an essay of them. She was in the Warsaw ghetto under terrible conditions, and then was sent to Bergen-Belsen. She said that the people on the train had been hurriedly jammed into cars and sent on a meandering journey back and forth across central Germany to escape the British, American, and Russian troops. The attempt was evidently to get them to a camp where they could be eliminated before they could be liberated.

“Also tremendously moving were their smiles. I have one picture of several girls, specter-thin, hollow-cheeked, with enormous eyes that had seen much evil and terror, and yet with smiles to break one’s heart. Little children came around with shy smiles, and mothers with proud smiles happily pushed them forward to get their pictures taken. I walked up and down the train seeing some lying in pain or lack of energy, and some sitting and making hopeful plans for a future that suddenly seemed possible again. Others followed everywhere I went, not intruding but just wanting to be close to a representative of the forces that had freed them. How sad it was that we had no food to give immediately, and no medical help, for during my short stay with the train sixteen or more bodies were carried up the hillside to await burial, brave hearts having lost the fight against starvation before we could help them.

“The boxcars were generally in very bad condition from having been the living quarters of far too many people, and the passenger compartments showed the same signs of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. But the people were not dirty. Their clothes were old and often ragged, but they were generally clean, and the people themselves had obviously taken great pains to look their best as they presented themselves to us. I was told that many had taken advantage of the cold stream that flowed through the lower part of the valley to wash themselves and their clothing. Once again I was impressed by the indomitable spirits of these courageous people.”

I find this picture very moving: mothers love to show off their youngsters, no matter what the situation. The little fellow was pleased at having his picture taken. Note the thin legs and brave smile.

“I spent part of the afternoon listening to the story of Gina Rappaport, who had served so well as interpreter. She was in the Warsaw ghetto for several years as the Nazis gradually emptied the ghetto to fill the death camps, until her turn finally came. She was taken to Bergen-Belsen, where the horrible conditions she described matched those official accounts I later heard. She and some 2500 others, Jews from all over Europe, Finnish prisoners of war, and others who had earned the enmity of Nazidom, were forced onto the train and taken on a back-and-forth journey across Germany, as their torturers tried to get them to a camp where they could be eliminated before Russians on one side or Americans on the other caught up with them. Since the prisoners had little food, many died on the purposeless journey, and they had felt no cause for hope when they were shunted into this little unimportant valley siding. Gina told her story well, but I have never been able to write it. I received a letter from her months later, when I was home in San Diego. I answered it but did not hear from her again. Her brief letter came from Paris, and she had great hopes for the future. I trust her dreams were realized.

“We were relieved the next morning, started up the tank, waved good-bye to our new friends, and followed a guiding jeep down the road to rejoin our battalion. I looked back and saw a lonely Gina Rappaport standing in front of a line of people waving us good fortune. On an impulse I cannot explain, I stopped the tank, ran back, hugged Gina, and kissed her on the forehead in a gesture I intended as one asking forgiveness for man’s terrible cruelty and wishing her and all the people a healthy and happy future. I pray they have had it.”

“This is a view of the train from the rear, showing boxcars like those in picture 1. On the hill to the left are people resting–some forever. Some sixteen died of starvation before food could be brought to the train.”

“This one, too, is very moving. My original note says, ‘The little girl in the middle is so weak from starvation she can hardly stand–yet she has a smile for her ‘liberators.” One might say exactly the same of the two children on either side.”

Long Time, No See!

Thanks to Matthew’s story, the story got out. ‘Then, the first miracle happened,’ he notes. ‘I heard from my first Holocaust survivor now living in Australia, a grandmother who had been a little girl on the train. In short order I heard from a doctor in London, a scientist in Brooklyn, and a retired airline executive in New Jersey. So I decided to host a reunion for them at our school. Judge Walsh met them with a laugh, and said, “Long time, no see!”’

Dr. Tomkiewicz, professor of Environmental Studies and Physics at Brooklyn College, sai of the reunions: ” Mr. Tomkiewicz said of the Reunion, “Suddenly, we had names. We could shake hands. We could put our own background in a context we couldn’t put before; this was an event that crystallized the scenario.”

Words From the Saved:

‘It was a beautiful, balmy morning in April 1945, when I entered Major Adams’ makeshift office in Farsleben, a small town in Germany, to offer my services as an interpreter. It made me feel good that I could show, in a small way, the gratitude I felt for the 9th American Army, which had liberated us as we were being transported from Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

‘Orders found by the Americans in the German officer’s car directed that the train was to be stopped on the bridge crossing the Elbe River at Magdeburg, then the bridge was to be blown up, also destroying the train and its cargo all at once. The deadline was noon, Friday the 13th, and at 11 A.M. we were liberated!

‘With the liberation had come the disquieting news that President Roosevelt had died, and while I was airing concern that the new President, Harry Truman, (a man unknown to us) could continue the war, a sergeant suddenly said, “Hey, you speak pretty good English. I am sure the major would like to have you serve as his interpreter.”

‘Major Adams had not been told of my coming, so he was startled when he saw me. No wonder! There stood a young woman as thin as a skeleton, dressed in a two-piece suit full of holes. The suit had been in the bottom of my rucksack for 20 months, saved for the day we might be liberated, but the rats in Bergen-Belsen must have been as hungry as we were and had found an earlier use for my suit. For nine days we had been on the train, and this was the only clean clothing I owned.

‘Major Adams quickly recovered from his initial shock and seemed delighted after I explained why I had come. He asked how his men had treated us, and I heaped glowing praise on the American soldiers who had shared their food so generously with the starving prisoners. Then he took me outside to meet the “notables” of the German population, and with glee I translated orders given to them by the American commander. The irony of the reversal of roles was not lost on me nor the recipients; I was now delivering orders to those who had been ordering me around for so long! The Germans were obsequious, profusely claiming they never wanted Hitler or agreed with his policies and hoped the war would soon be over.

‘When asked to come back the next day, I was delighted but hesitated, wondering if it would be appropriate to ask a favor. Major Adams picked up on my hesitation, so I asked him to help me contact my family in America. We had emigrated to the U.S. in 1939, but after six months I returned to Holland to join my fiancé who was in the Dutch army. My parents knew that eight months after we were married my husband was taken as a hostage and sent to Mauthausen concentration camp where he was killed in 1941, but they did not know if I was alive, not having heard from me in more than two years.

‘Major Adams gave me a kind glance, saying, “Give me a few handwritten lines, in English, and I will ask my parents to forward the letter to them.”

‘When he saw the address on the note he looked at me, his mouth open in total amazement, and then he started to laugh – his parents and my parents lived in the same apartment building in New York City!

‘And so it was on Mother’s Day that his mother brought to my mother my message:

“I am alive!”’

– Lisette Lamon, a Holocaust survivor“I survived because of many miracles. But for me to actually meet, shake hands, hug, and cry together with my liberators–the ‘angels of life’ who literally gave me back my life–was just beyond imagination.’

– Leslie Meisels, Holocaust Survivor“We’d heard stories about the mistreatment of Jews, about them being tortured and being put to death, but we dismissed what we thought was propaganda. We didn’t believe one group of human beings could do that to another group of human beings. It wasn’t until we saw this trainload of Jews that we believed.”

– Army first lieutenant Frank Towers, Liberator‘I cannot believe, today, that the world almost ignored those people and what was happening. How could we have all stood by and have let that happen? They do not owe us anything. We owe them, for what we allowed to happen to them.’

– Carrol Walsh, Liberator

World War II infantry veteran Carrol Walsh, top, hugs Holocaust survivor Paul Arato at a reunion in Queensbury, N.Y., on Tuesday, Sept. 22, 2009. “Please give me a hug. You saved my life,” Arato told Walsh. Mr Arato was just 6 when he was rescued. A GI gave him a Tootsie Roll. He never forgot it.

Carrol Walsh died on Dec. 17th, 2012. He was 91. A retired state judge whose account of liberating Holocaust victims from a Nazi train led to reunions with the survivors 60 years later. “He’s the catalyst for everything,” said Matthew. “All of these people, men, women, children, jam-packed in those boxcars, I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Walsh said in 2001. “And there they were. So, now they knew they were free, they were liberated. That was a nice, nice thing.”

Matthew Rozell continues his compelling work at his excellent website Teaching History Matters. After the war, the woman and her daughter seen above in the haunting moment captured by Major Benjamin retuned to their native Hungary. They did not want to be identified.

You can read more about the train and people who came together one day in 1945 in Matthew’s excellent book : A Train Near Magdeburg: A Teacher’s Journey into the Holocaust, and the reuniting of the survivors and liberators, 70 years on.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.