Albert Allick Bowlly, who some say invented ‘crooning’ or as he called it “The Modern Singing Style” – an expressive style of singing that took advantage of the invention of the microphone in 1931 – was an incredibly influential singer before World War 2. Women, in particular, were susceptible to his not inconsiderable vocal charms. The band leader Ray Noble once said of Al Bowlly that he often stepped away from the microphone with tears in his eyes: “never mind him making you cry, he could make himself cry!” Bowlly died during a terrible air-raid in 1941 although his music lives on and has featured in some of the most famous ‘cult’ films of the last few decades including The Shining, Amelie and Withnail and I.

Bowlly was born in Mozambique, then a Portuguese colony, to Greek and Lebanese parents who met en route to Australia but moved to South Africa. After travelling and busking his way to Europe he made his first recording in 1927 in Berlin with Irving Berlin’s Blue Skies. He then came over to London as part of the Fred Elizalde’s orchestra. Their version of ‘If I Had You’ became a hit in America – maybe the first British jazz record to do so. It wasn’t initially a smooth ride to fame for Bowlly the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 meant that he had to return to several months of busking to survive. In wasn’t too long, however, before he signed two contracts — one in May 1931 with Roy Fox, singing in his live band for the Monseigneur Restaurant in London, the other a record contract with Ray Noble’s orchestra in November 1930.

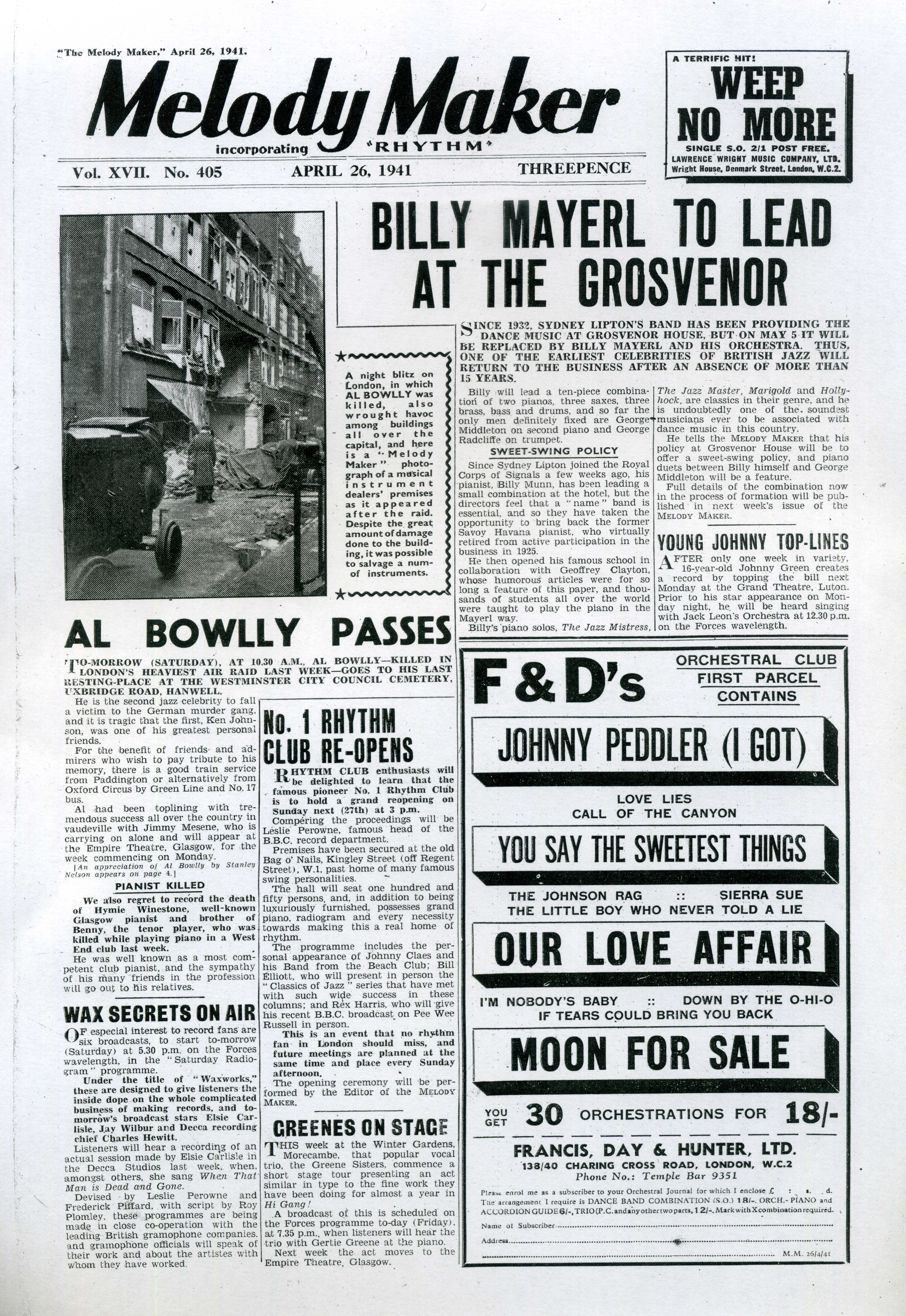

“Without any shadow of a doubt,” the Melody Maker announced, Bowlly is “the leading style singer in the country. His phrasing, diction and intonation are superb, whilst the individualism he manages to get into his renderings is really amazing.”

Al Bowlly sings “The Very Thought of You” in 1934 for Pathé.

Al Bowlly

In the early days of amplified singing microphones were not necessarily always available and Bowlly featured in a an advert in Melody Maker where ‘Britain’s most outstanding dance vocalist’ expounded the “Al Bowlly ultra compact Megaphone” – a new loud speaker for vocalists!” Although he used them he disliked megaphones as they would hide his face.

During the next four years, he recorded over 500 songs. By 1933 Lew Stone had ousted Fox as bandleader, and Bowlly was singing Stone’s arrangements with Stone’s band. After much radio exposure and a successful British tour with Stone, Bowlly was inundated with demands for personal appearances and gigs—including undertaking a subsequent solo British tour—but continued to make the bulk of his recordings with Noble.

With Ray Noble, Bowlly travelled to New York City in 1934 which resulted in more success, and their recordings first achieved popularity in the United States; he appeared at the head of an orchestra hand-picked for him and Noble by Glenn Miller. During the mid-1930s, such songs as “Blue Moon”, “Easy to Love”, “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” and “My Melancholy Baby” became American hits. His growing popularity in the US meant that Bowlly gained his own radio series on NBC and traveled to Hollywood to co-star in 1936 with Bing Crosby, one of his biggest competitors, in The Big Broadcast.

His absence from the UK when he moved to the States in 1934 damaged his popularity with British audiences. His career began to suffer as a result of problems with his voice from around 1936, which affected the frequency of his recordings. He played a few small parts in films around this time, yet never professed to be an actor. The parts he did play were often cut, and scenes that were shown were brief. Noble was offered a role in Hollywood although the offer did not, unfortunately, include Bowlly, as a singer had already been instated. Bowlly moved back to London with his wife Marjie in January 1937.

With his diminished success in Britain, he toured regional theatres and recorded as often as possible to make a living, moving from orchestra to orchestra, including those of Sydney Lipton, Geraldo and Ken Johnson. He underwent a revival from 1940, as part of a double act with Jimmy Messene (whose career had also suffered a recent downturn, not least because of excessive drinking), with an act called Radio Stars with Two Guitars, performing on the London stage. It was his last venture before his death in April 1941.

Bowlly’s last recorded song was, like his first, by Irving Berlin – the satirical song on Hitler called “When That Man is Dead and Gone”. Two weeks later Bowlly gave a performance at the Rex Cinema in High Wycombe. Although offered an overnight stay in the town he decided to take the last train home to his flat at 32 Duke’s Court in Duke Street in St James, London. When he reached London there was a ferocious air-raid on but by the time he had walked back home from Marylebone station he was in bed at just after midnight and started to read a book of cowboy stories.

It was said that Bowlly’s relaxed attitude to the Blitz came from one of the first daylight raids of the war, when he had been walking along Brewer Street in Soho. A bomb exploded in the middle of the road in front of him but all the force of the blast went in the opposite direction – leaving him unscathed. From that point he often ignored the sirens, feeling almost invincible.

Bowlly was asleep when in the early hours of 17 April 1941, a large parachute bomb floated down above St James’s. At around 3.10 a.m. it exploded just above the corner of Jermyn Street with Duke Street St James. Parachute bombs, or landmines as they were often called (they were originally designed as mines to be used in water with a magnetic detonator), were built to explode in the air just above their target so that without protective cover the resultant shockwaves would flatten whole streets, with windows breaking up to a mile away. In this particular case the destruction was savage. The famous Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street, once said to be the finest Turkish bath in Europe, was razed to the ground while other premises badly damaged were Fortnum & Mason, the Cavendish Hotel, Dunhill’s and the southern end of the Piccadilly Arcade. Many of the serviced flats in Duke’s Court also took the full force of the 1,000 kg bomb.

It wasn’t just St James’s that suffered during the Luftwaffe bombing raids on the night of 16/17 April. As far as London was concerned, it was one of the worst of the war and became known, simply, as ‘The Wednesday’. Over a seven-hour period about 1,000 tons of incendiaries and high explosives rained down on the capital. This time it wasn’t the East End that took the brunt, but much of central and west London, with the West End in particular taking a battering. It was estimated that 1,180 London civilians died that night or soon after, with 2,230 seriously injured. The diarist Anthony Heap wrote: ‘About the worst “blitz” we’ve yet experienced broke over London after 9 p.m. last night and lasted a good seven hours. It took us right back to last September, though neither then nor since has there been anything to match the raid for non-stop intensity.’ The novelist Graham Greene who was a bomb warden that night in the West End wrote years later that the night was ‘the worst raid Central London had ever experienced’.

Although there were no real numbers of casualties, the newspapers on the 18th, despite the usual lack of details, acknowledged the devastation across London. The Daily Express reported: ‘The vicious air raid on London on Wednesday night – it was the worst the capital has experienced – caused heavy casualties, it is officially reported. High explosives and fire bombs were rained down hour after hour until dawn brought relief. One of the districts most affected was the West End, where shop and office workers yesterday morning had to wade through piles of shattered glass and wreckage.’ The newspaper added that Lord and Lady Stamp and Mr Wilfrid Carlyle Stamp, their eldest son and heir to the title, were killed in the raid, as was ‘Lord Auckland (an expert in animal taming)’. Almost as an afterthought the newspaper mentioned the death of ‘well-known crooner’ Al Bowlly.

When the all-clear sounded around dawn on the 17th April the caretaker of Dukes Court went round to check on the safety of his tenants. It had been one of the worst bombing raids on London of the Blitz. The night would be forever known as ‘The Wednesday’. The caretaker found Al Bowlly on the floor by the side of his bed killed outright by the door of his room smashing on his head from the blast of the parachute bomb. Two friends of Bowlly’s also lived in the same apartment block. The pianist Monia Liter who had been in Bangor the previous day and had known Bowlly since 1929. When as a pianist and leader of his own orchestra he had employed the young vocalist at Raffles the famous hotel in Singapore and subsequently had been his accompanist on Bowlly’s solo records. When Liter arrived back at the apartment block in Jermyn Street he met in the hall the comedienne and actress Beatrice Lillie, another inhabitant of the serviced flats. He later recalled: “When I got back to Jermyn Street on the morning after the raid, Bea Lillie met me in the hall. She said ‘We’ve had a terrible night – look here’, and showed me a number of large sacks in the hall with labels on them. ‘These are the people who were killed last night.’ I saw that one of the sacks had Al Bowlly’s name on the label. It was a terrible shock.” Lillie’s own son died a year later killed in action aboard HMS Tenedos (H04) in Colombo Harbour, Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). An inveterate entertainer of the troops she heard about her son’s death just before she was about to go on stage. She refused to postpone the performance saying “I’ll cry tomorrow.”

Bowlly’s remains were taken to the local Council’s mortuary at Glasgow Terrace and a death certificate was eventually produced which misspelt Bowlly’s name and gave the cause of death as “due to war operations”. He was buried in a mass communal grave on Saturday 26th April at 10.30am at the Westminster City Council Cemetery on the Uxbridge Road in Hanwell. Jimmy Mesene tried to make arrangements for a proper tombstone for Al Bowlly to be erected. The required licence was refused by Westminster City Council, however, for the reason that it would set a precedent – the section of the cemetery was designated as a war grave and private memorials were not allowed.

Al Bowlly sings “My Melancholy Baby” in 1934 for Pathé

This is an excerpt from the acclaimed book High Buildings, Low Morals

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.