THE found-footage horror film genre is one that isn’t often appreciated. The late Roger Ebert himself once wrote that movies of this type often consist of “low quality home video footage,” are “usually under-lit,” are “lacking in pacing” and seem “intentionally hard to comprehend.”

Indeed, there seems to be the pervasive misconception that a found-footage horror movie is somehow easy to shoot and produce. You don’t need a star, for example, or much of a budget either, to make such a film. You don’t even need expensive equipment.

All an intrepid film crew needs is a good concept, and a whole lot of shakin.’

None of this is true.

A good found-footage horror film — while cut-off in large part from the elegance, structure, and language of traditional film grammar — nonetheless has its merits.

For one thing, found-footage films ramp-up the experiential or immersing aspects of the genre. The hand-held camera-work provokes a brand of immediacy and urgency that other horror sub-genres can’t necessarily emulate.

Horror movies in general concern situations that are impossible to escape, set in isolated locations. The found-footage genre runs with this idea, landing its stars in frightening landscapes and then charting a kind of pressure-cooker intensity as terror boils over.

For another thing, the compositions in found-footage films must appear spontaneous and on-the-fly, all while simultaneously capturing crucial action. This balancing act requires quite a bit of legerdemain.

A unique development of cinema-verite documentary techniques, the found-footage horror film thus requires patient preparation of shots, split-second timing, long takes, and a certain brand of non-theatrical or “naturalistic” performance that not every actor can easily master.

The overt critical dislike and disregard for the found-footage genre reminds me very much of the critical hand-wringing that occurred in the 1980s over the slasher movie formula, or in the mid-2000s over so-called “torture porn.”

Basically, movie critics are always finding some reason to object to horror’s latest trend, even as audiences are ahead of the curve, and excavating reasons to appreciate the new format.

In short, a good found-footage film — such as the genre’s classic, The Blair Witch Project (1999) — isn’t just a case of point-and-run film-making. In The Blair Witch, for instance, artistry can be detected in the escalation of the film’s throat-tightening terror, and there is even a clever sub-text about the camera operating as a “filter” that occludes reality.

The found-footage film genre has many undisputed highs, from [REC] (2007) to Trollhunter (2008), but the five found-footage horror films featured below have generally been dismissed by critics, even though they possess abundant virtues not necessarily associated with this derided sub-genre.

1. Apollo 18 (2011)

You know your movie has been poorly received when it is the butt of a joke in another found-footage horror movie (Grave Encounters 2 [2012]).

But reception aside, Apollo 18 boasts a value that found-footage movies aren’t supposed to reflect: excellent production design.

The movie is actually a period piece, set in 1972, during the last days of NASA’s Apollo program. The film concerns a failed space mission to the moon, and the discovery of terrible creatures on the lunar surface.

In this case, tremendous attention has been paid to making certain that the film’s sets and wardrobes are appropriate and correct to the disco decade epoch. The film grain is right too, and the result is that Apollo 18 looks very much like footage of a real space program venture. The retro (low) tech wonders of the film are actually quite remarkable, from the Lunar Lander interior and astronaut spacesuits to the Rover mock-up. There is no hint in the visuals that this is modern fakery.

Similarly, if the game of the found-footage movie is to find an inhospitable or dangerous terrain, and then chart the mental and physical disintegration of the characters’ trapped there, then Apollo 18 must represent an apotheosis of sorts. The whole movie is set on Earth’s moon. The vast, desolate landscape is recreated ably on a low budget, and viewers understand immediately that this is a realm of a million dangers, and virtually no sanctuary whatsoever.

With convincing mock-ups and locations, Apollo 18 asks its audience to dwell, essentially, in an extended moment of fear and isolation, with no genuine hope of escape. One touching moment involves an astronaut — knowing he shall never see home again — playing a recording of his wife and son over and over; reaching out for something, anything human and comforting.

Again, critics want to tell you the characters in the film are indistinguishable and you never care about them. But this scene of human longing and separation puts truth to that lie.

2. Grave Encounters (2011)

Again, this is a found-footage movie that received largely negative reviews, but a positive audience response. And again, it boasts an intellectual or aesthetic quality that found-footage movies supposedly don’t possess: satirical insight.

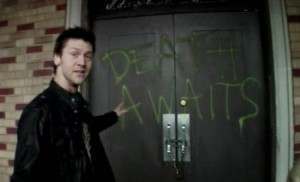

In this case, the filmmakers mercilessly and humorously roast reality-TV conventions, and especially those of the Ghost Hunter-type show variety. In programs of this type, every little cold spot and door squeak is made into a paranormal event of historical proportions. Accordingly, Grave Encounters involves a team of reality-star wannabes, led by Lance Preston (Sean Rogerson), as these actors investigate a purportedly haunted mental institution.

In short order, the audience sees Lance pay a gardener on the sanitarium grounds twenty-dollars to claim that he’s seen ghosts. And the group’s psychic, Houston, is worried about possibly missing an important audition. When Houston goes “big” and suggests that there’s a demonic presence in the asylum, he asks — after the take — if was “too much.”

What Grave Encounters tells audiences is that everything you see on reality TV is phony.

Of course, horror movies must punish those who transgress, and these narcissists in Grave Encounters soon find themselves in a hospital where there is no escape. The asylum seems to rewrite reality itself, and the blasé actors – who have used real life tragedy as the source for their “drama” and stardom – are suddenly faced with a true understanding of madness.

Grave Encounters bucks all the stereotypical criticisms of the found-footage genre, and meaningfully (and scarily…) critiques an aspect of our culture: the quest for fame at all costs.

3. Paranormal Activity 3 (2011)

The best of the durable Paranormal Activity films, Paranormal Activity 3 is simply a superior scare machine.

It features some of the best jump scares in the franchise, and more than that, does so by generating the rare quality of attention, or patience. Again, critics of the found-footage format want to convince audiences that these films are slap-dash cash grabs that appeal to the lowest-common denominator. They’re cheap and gimmicky!

If that’s the case, how does one account for a film like Paranormal Activity 3, which possesses long stretches of silence and stillness, and demands engagement on the part of the viewer? Here is a film that instead of rewarding a short attention span, rewards patience.

So much of this sequel’s running time is devoted to a camera panning back and forth in a room, or the quiet recording of apparently vacant areas of a suburban house. This technique not only generates suspense, it encourages one to look closely at absolutely everything, to make a mental snapshot in your head of what item is where, what light is turned on, and what, if anything, is moving in the frame.

In a way, this very technique mirrors how it feels to wake up, sleepily, in the middle of the night (after hearing a noise) and scanning the environs. Paranormal Activity 3 is all about the potent idea of sleepy twilight, of being awake at 3:15 in the morning, and not quite having an accurate sense of what is going on. The world is at slumber — or should be — but something insidious lurks just at the edges of perception.

We’ve all experienced this feeling, and can relate to the characters’ situations.

4. V/H/S (2012)

The first found-footage anthology, this omnibus film is a social commentary on the fact that the home video revolution of the 1980s — now thirty years old — has transformed all of us into directors, actors, historians, journalists…even porno stars.

Imagine for a moment millions of people possessing home movie tapes, and then imagine what becomes of those tapes after three decades.

In whose hands to they end up? What purpose do they serve? What value do they possess?

V/H/S explore five unsettling genre stories vetted from a first-person perspective, and the wraparound narrative device involves a group of small-time miscreants desperately searching for one particular video tape in the house of a (presumably) dead tape collector.

Several tapes are viewed, and all are recordings of dark, sinister events. In virtually every situation, the video camera is used to hurt someone: to trick a gullible woman into sex, to record a carefully-plotted murder, to convince a scared girlfriend not to seek help when something strange starts happening to her, and so forth.

I once called this film “America’s Scariest Home Videos,” but it’s more than that: V/H/S is s chronicle of the weird turn that the home video revolution has taken.

Today, we have cameras on our phones and on our tablets, and we have the capacity to record our entire lives. But what if we are recording something else too? What if all the recording technology of the last thirty years is merely creating a tapestry of suffering and inhumanity? What if we are simply documenting our cruelty?

Again, it’s all too easy to dismiss this film (and its good, 2013 sequel as well…) as a gore-fest, but V/H/S explores – in horrifying fashion – the nexus of modern technology and modern morality.

5. The Devil’s Pass (2013)

This found-footage effort from Renny Harlin starts out as a meticulous exploration of the (still-unsolved) Dyatlov Pass Incident in Russia. A group of hikers died under mysterious circumstances in 1959, on the so-called “Mountain of Death.”

A film that seems in danger of being a simple Blair Witch Project knock-off, however, instead showcases something else that found-footage movies are often accused of lacking: imagination.

Before The Devil’s Pass is over, the movie has devised a (crazy…) solution to the real-life mystery, offered up a unified theory of conspiracies and the paranormal, and even had the grace and literacy to wink at Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5. The movie incorporates Indian cave drawings and the Philadelphia Experiment, and ends with an audacious final twist that will leave your jaw agape.

Sure, the actors aren’t great, and the early scenes are clunky, but The Devil’s Pass’s final act runs on pure, unadulterated, gonzo imagination. The movie goes courageously for broke, breaking out of format conventions and generating a lingering horror that lasts long beyond the end credits.

Each one of the aforementioned films is worth watching, and each one puts truth to the lie that the found footage genre is running on empty.

Apollo 18 is an accomplished period piece, Grave Encounters a satire of reality TV culture and ethos, Paranormal Activity 3 a waking dream that requires active participation on the part of the audience, V/H/S a dedicated critique of our modern technology, and The Devil’s Pass is the most imaginative and daring horror film to come down the line in quite a while.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.