“What is important is to distinguish between good and bad photography,” Tina Modotti once said. “Photography which accepts all the limitations inherent in photographic technique and takes advantage of the possibilities and characteristics the medium offers, is good. Photography which is done, one may say, with a kind of inferiority complex, with no appreciation of what photography itself offers, is bad.”

Tina Modotti was born Assunta Adelaide Luigia Modotti Mondini on August 16, 1896 in Udine (a part of Italy between the Alps and the Adriatic). At the age of just 16 she travelled alone on the SS Moltke from Genoa to America in 1913 to live with her father and sister in San Francisco. According to Letizia Argenteri, author of Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution, she arrived on July 8 at Ellis Island declaring “herself to be single, five feet one inch tall, in good mental and physical health, and a student.” She carried with her “100 dollars and a train ticket for San Francisco, where her father and her sister Mercedes resided.”

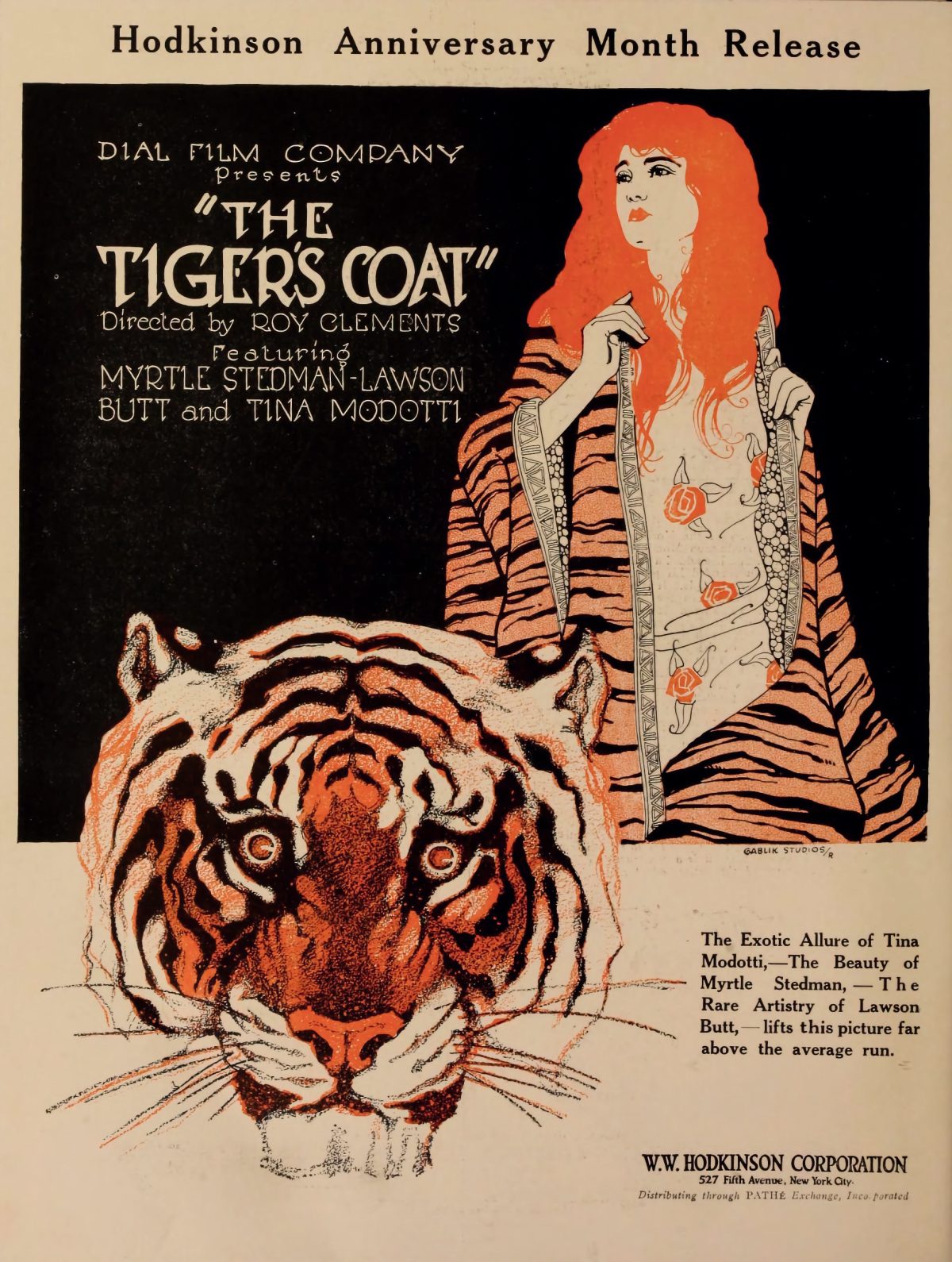

Modotti worked as an artist’s model during her first years in the country and acted in plays and silent films with her movie career culminating in the 1920 film The Tiger’s Coat released in 1920.

In the same year Modotti appeared in The Tiger’s Coat she met the photographer Edward Weston, who mentored her and was a great influence on her subsequent photographic work. By 1921 they had become lovers, and in 1923 they moved together to Mexico City – a cosmopolitan and cultural hotspot in the interwar years – and where they established a portrait photographic studio. They joined the Mexican Communist Party and became friends with political and artistic expatriate such as Sergei Eisenstein, Leon Trotsky, Lupe Marin and Jean Charlotte and moved in bohemian circles with Mexican intellectuals and artists such as Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

Tina Modotti and Frida Kahlo The relationship between the two women and their work is explored in Laura Mulvey’s 1983 short film, Tina Moddoti and Frida Kahlo, as well as depicted in the movie Frida, in which Modotti was played by American actress Ashley Judd

“I cannot, as you [Edward Weston] once proposed to me – solve the problem of life by losing myself in the problem of art … in my case, life is always struggling to predominate and art naturally suffers.”

– Tina Modotti

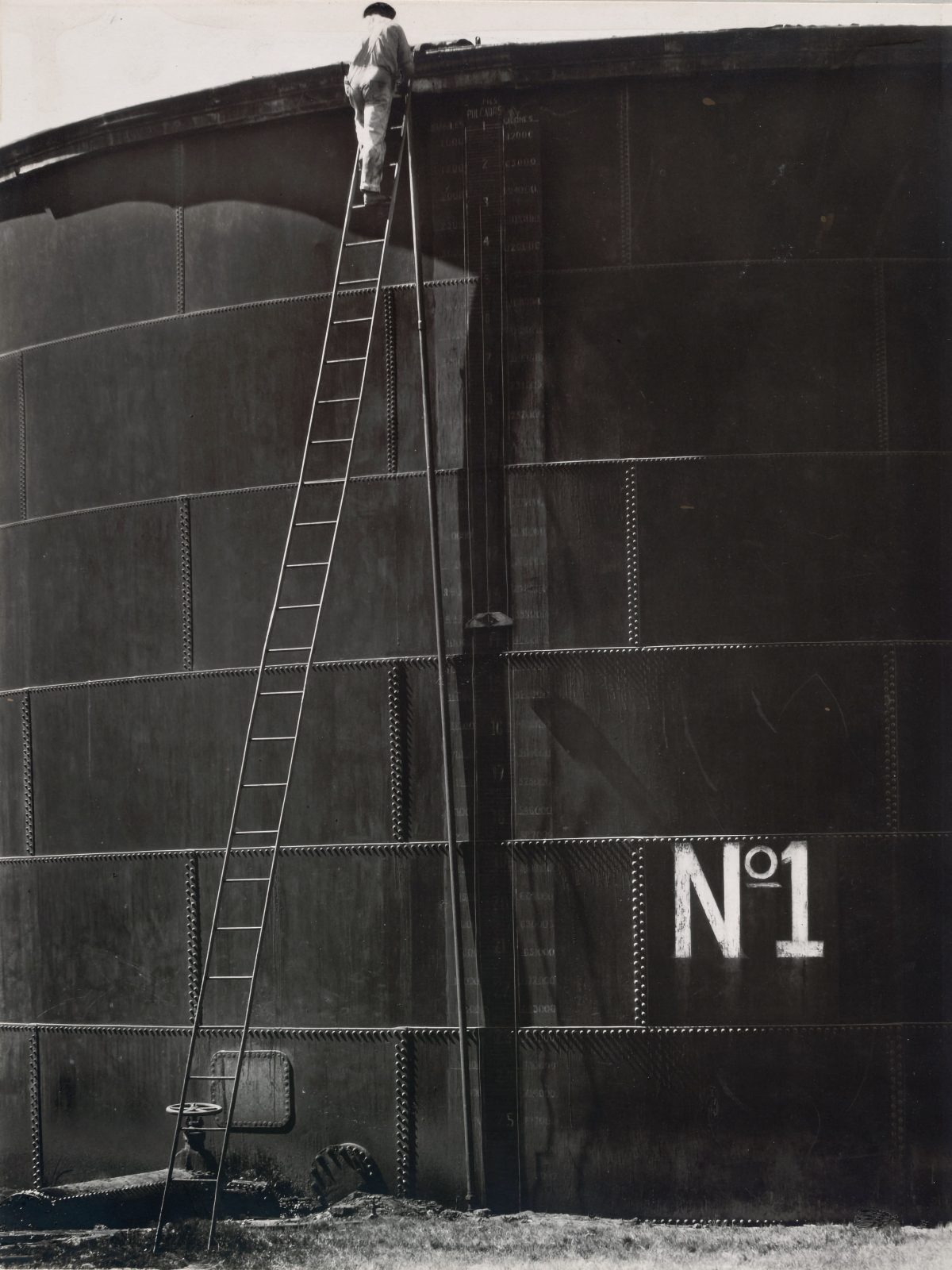

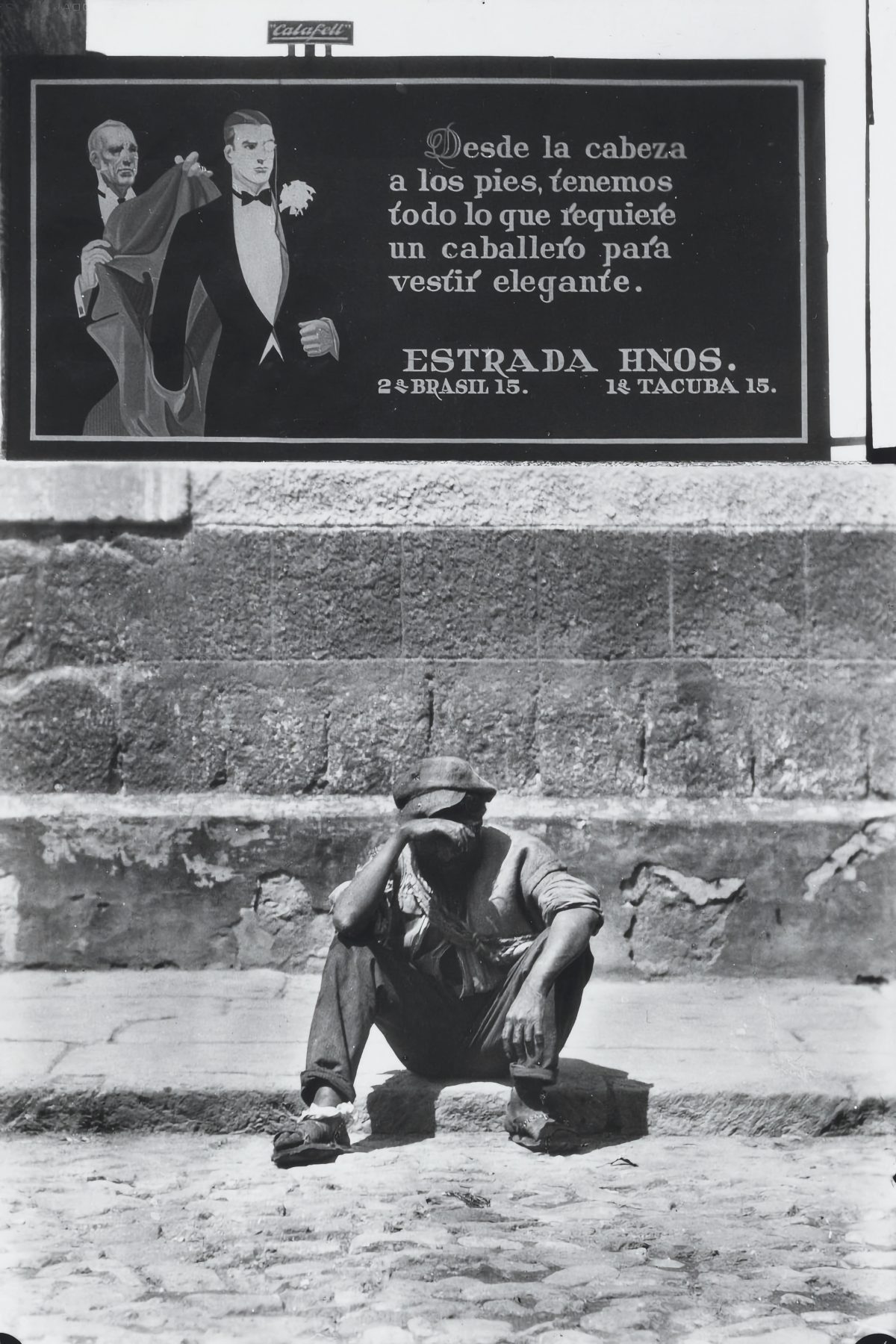

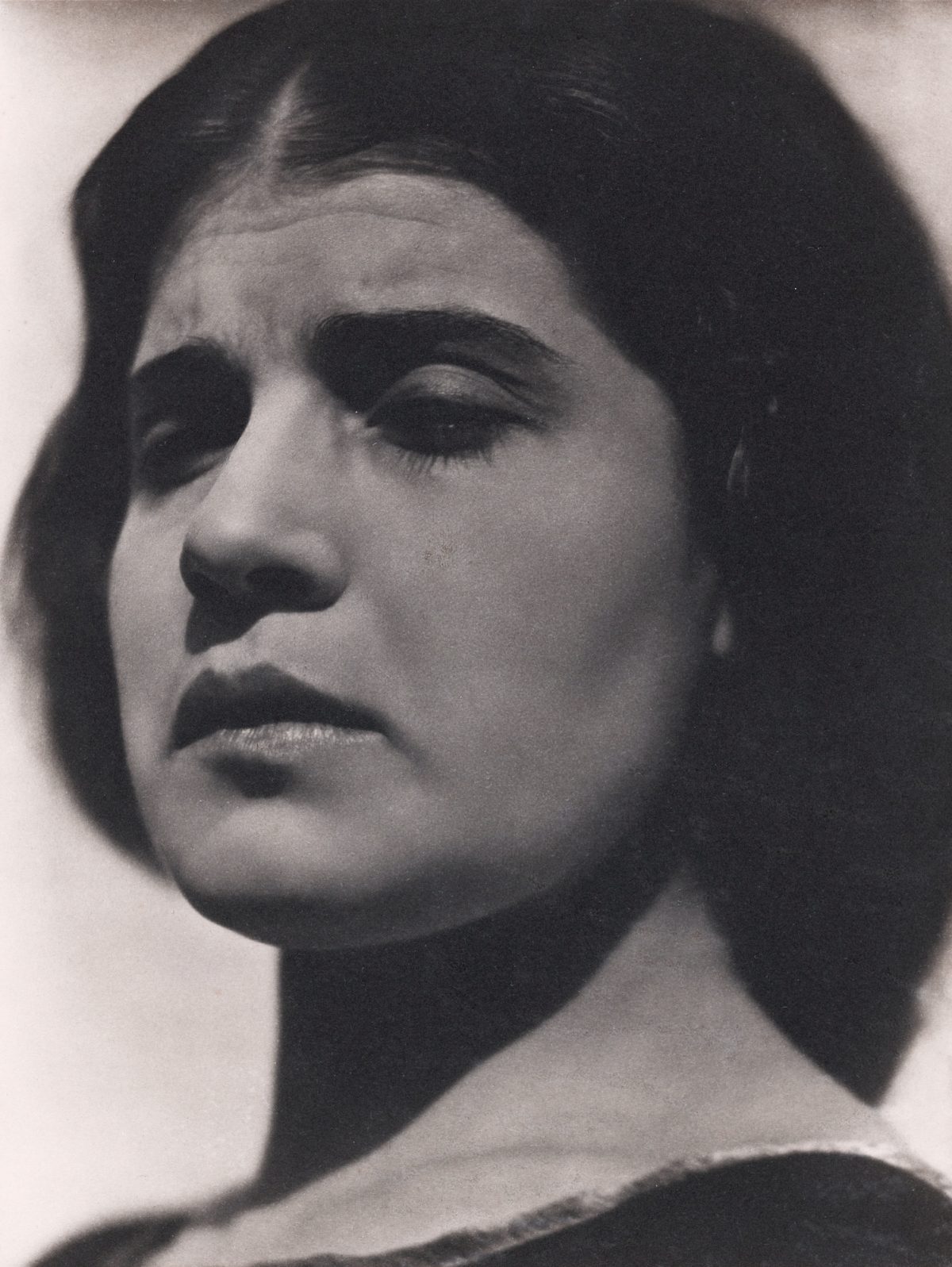

While Weston became inspired by the landscape and traditional folk-art of Mexico beginning to create abstract photographic work his partner Modotti became fascinated by the people of Mexico and their lives. She shunned the term ‘artist’ to describe herself and became intent on “capturing social realities”. She once stated:

Always, when the words art and artistic are applied to my photographic work, I am disagreeably affected. This is due, surely, to the bad use and abuse made of those terms. I consider myself a photographer, nothing more. If my photographs differ from that which is usually done in this field, it is precisely because I try to produce not art but honest photographs, without distortions or manipulations.

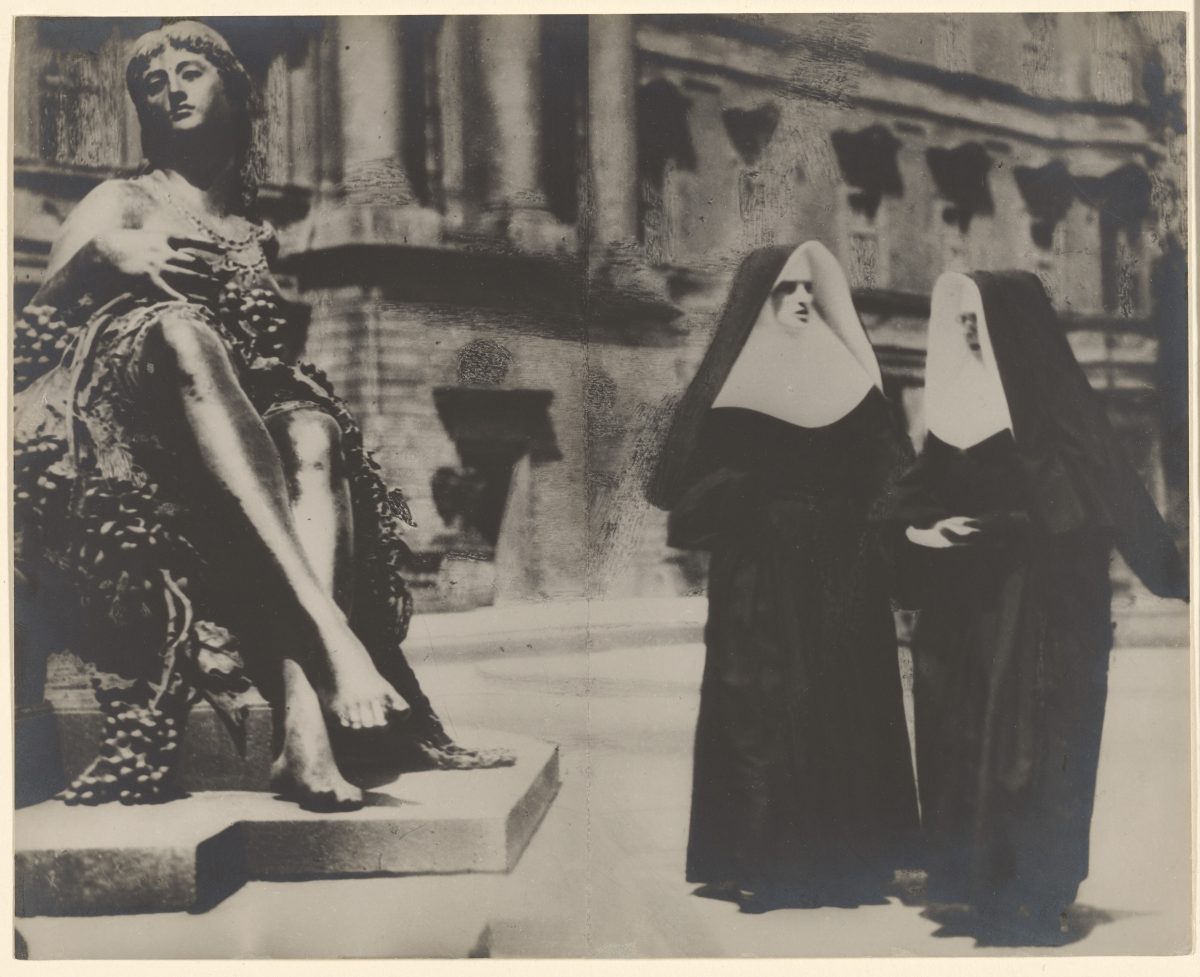

Modotti also became the photographer of choice for the blossoming Mexican mural movement, photographing people such as José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera and their works. Between 1924 and 1928, Modotti took hundreds of photographs of Rivera’s murals at the Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico City.

Weston would eventually go back to his wife in California whereas Modotti stayed in Mexico and in 1925 joined the International Red Aid (also commonly known by its Russian acronym MOPR) a Communist organisation that was meant to be an “international political Red Cross”, providing material and moral aid to radical “class-war” political prisoners around the world. According to Patricia Albers and Sam Stourdze in “Tina Modotti and the Mexican Renaissance” around this time Modotti met several political radicals and Communists, including three Mexican Communist Party leaders who would all eventually become romantically linked with her: Xavier Guerrero, Julio Antonio Mella, and Vittorio Vidali. By the way, Tina Modotti, who had many lovers but never married, once said:

I don’t believe in marriage. I think at worst it’s a hostile political act, a way for small-minded men to keep women in the house and out of the way, wrapped up in the guise of tradition and conservative religious nonsense.

In 1930 Modotti found herself in prison. The cuban activist Julio Antonio Mella had been assassinated while walking in the street with Modotti from the offices of the International Red Aid. Modotti – who was being watched by both the Mexican and Italian political police for her left-wing activism — was interrogated about the Mella assassination but also an attempt on the life of the Mexican soon-to-be-elected President Pascual Ortiz Rubio.

After 13 days in prison amidst a concerted anti-communist, anti-immigrant press campaign, that depicted “the fierce and bloody Tina Modotti”, the artist and prominent member of the Mexican Communist Party was eventually released and deported. Initially spending a few months months in Berlin followed by several years in Moscow. After 1931, Modotti no longer took any photographs none can be found anyway.

When the Spanish Civil War started in 1936 Modotti (using the pseudonym “Maria”) left Moscow for Spain, where she stayed and worked until 1939. Following the collapse of the Republican movement in Spain that year, Modotti left Spain and returned to Mexico under an assumed name.

On January 4, 1942, at the age of just 45, Modotti died on her way home in a taxi from dinner at the poet Pablo Neruda’s house. She had political enemies and although there were suspicions that she had been murdered. Diego Rivera, for instance, openly blamed Vittorio Vidali, a Stalinist with whom Modotti had a long affair, for her untimely death. An autopsy showed that she died of natural causes, specifically congestive heart failure. Her grave is to be found in the Panteón de Dolores cemetery (the largest in Mexico). The poet Pablo Neruda composed Modotti’s epitaph, part of which can also be found on her damaged tombstone, which also includes a relief portrait of Modotti by engraver Leopoldo Méndez.

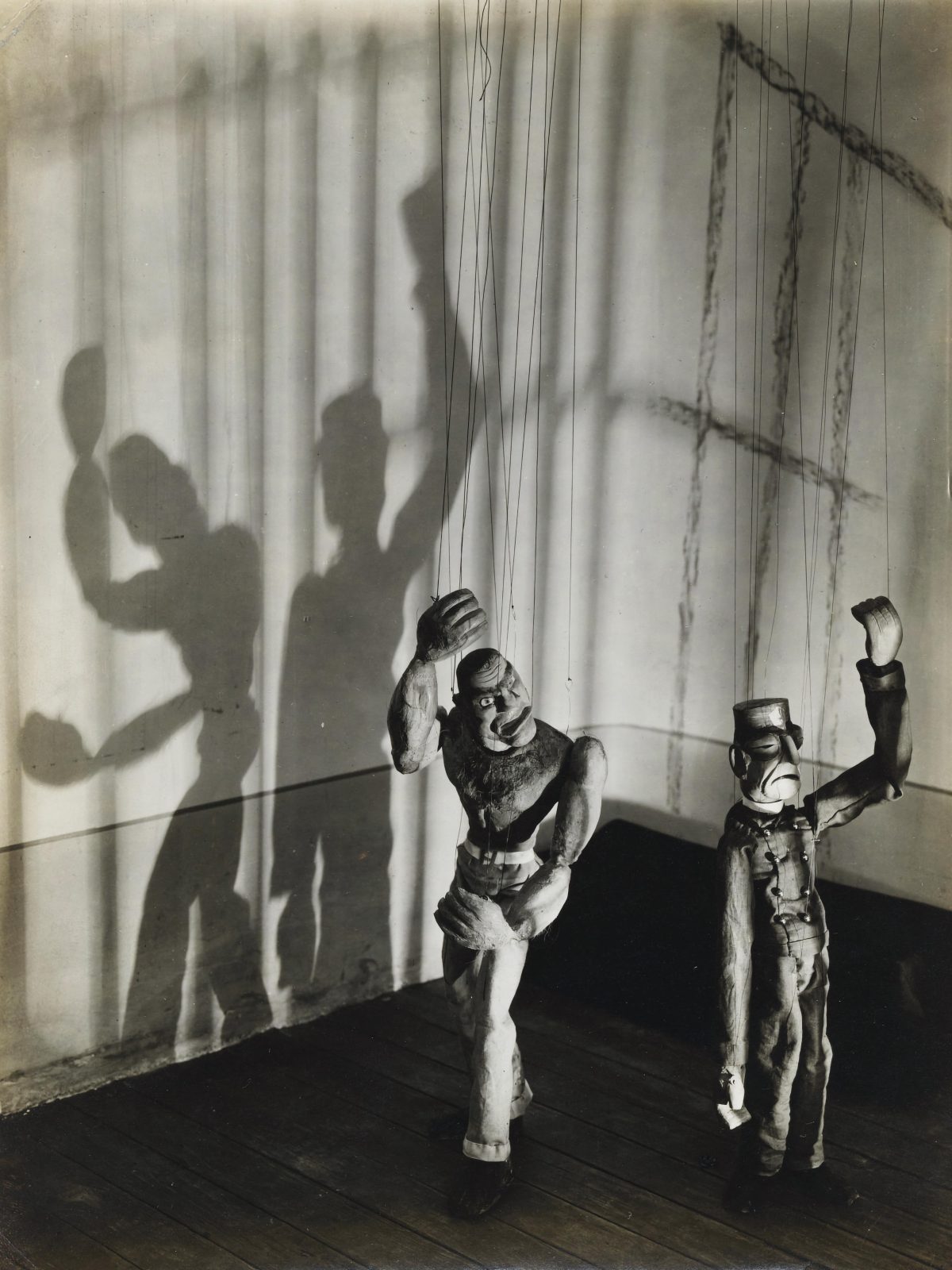

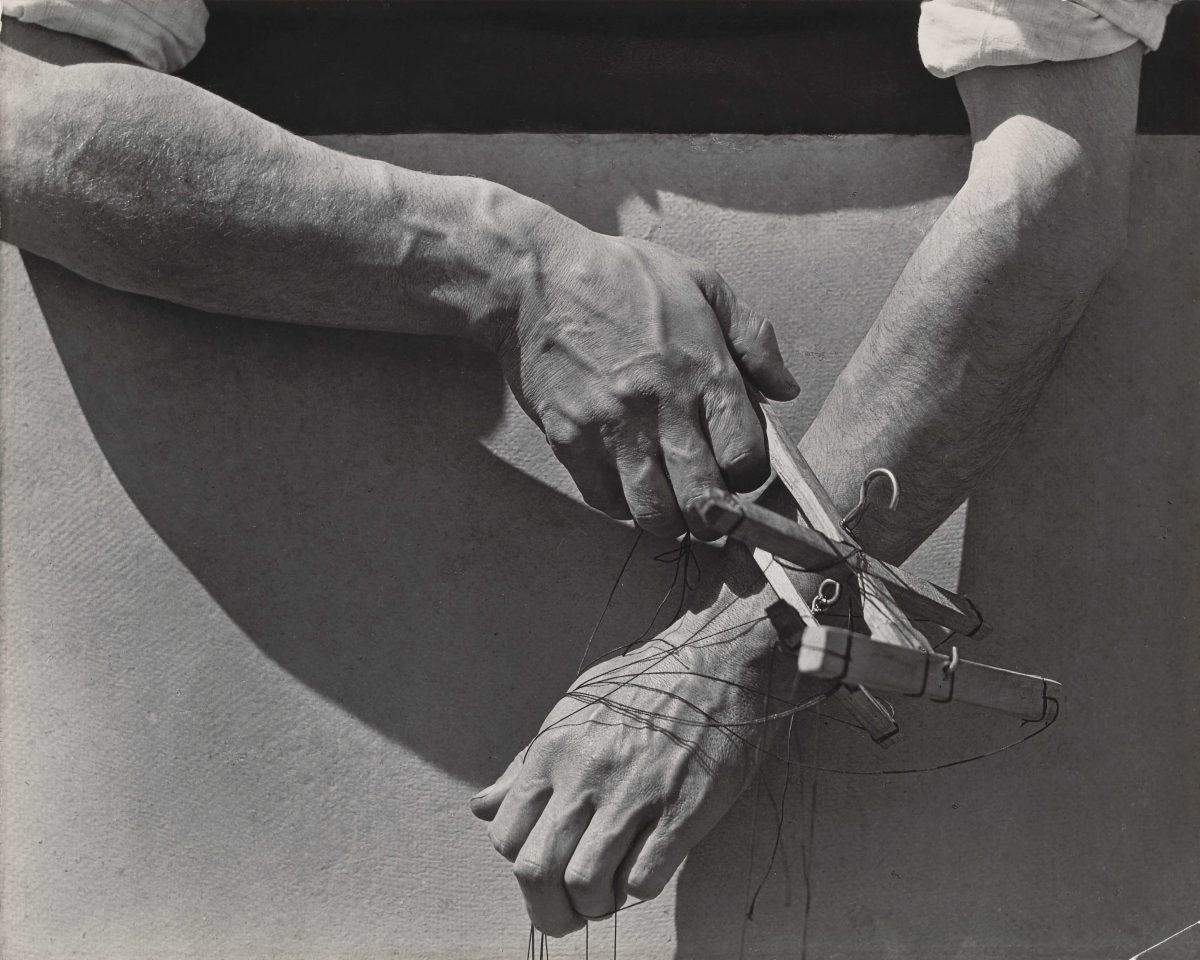

Hands of Marionette Player, 1929 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

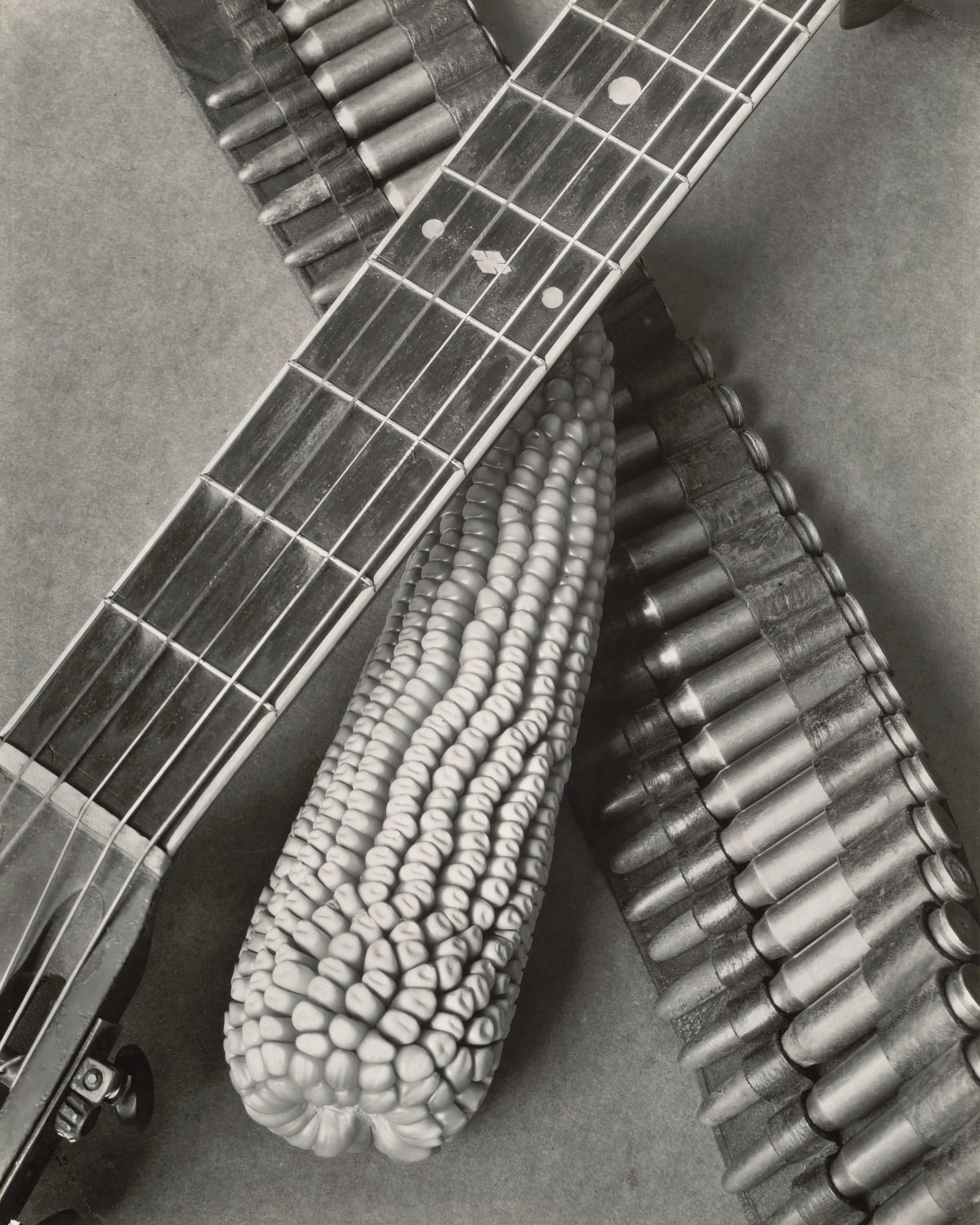

Illlustration for a Mexican Song 1927 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

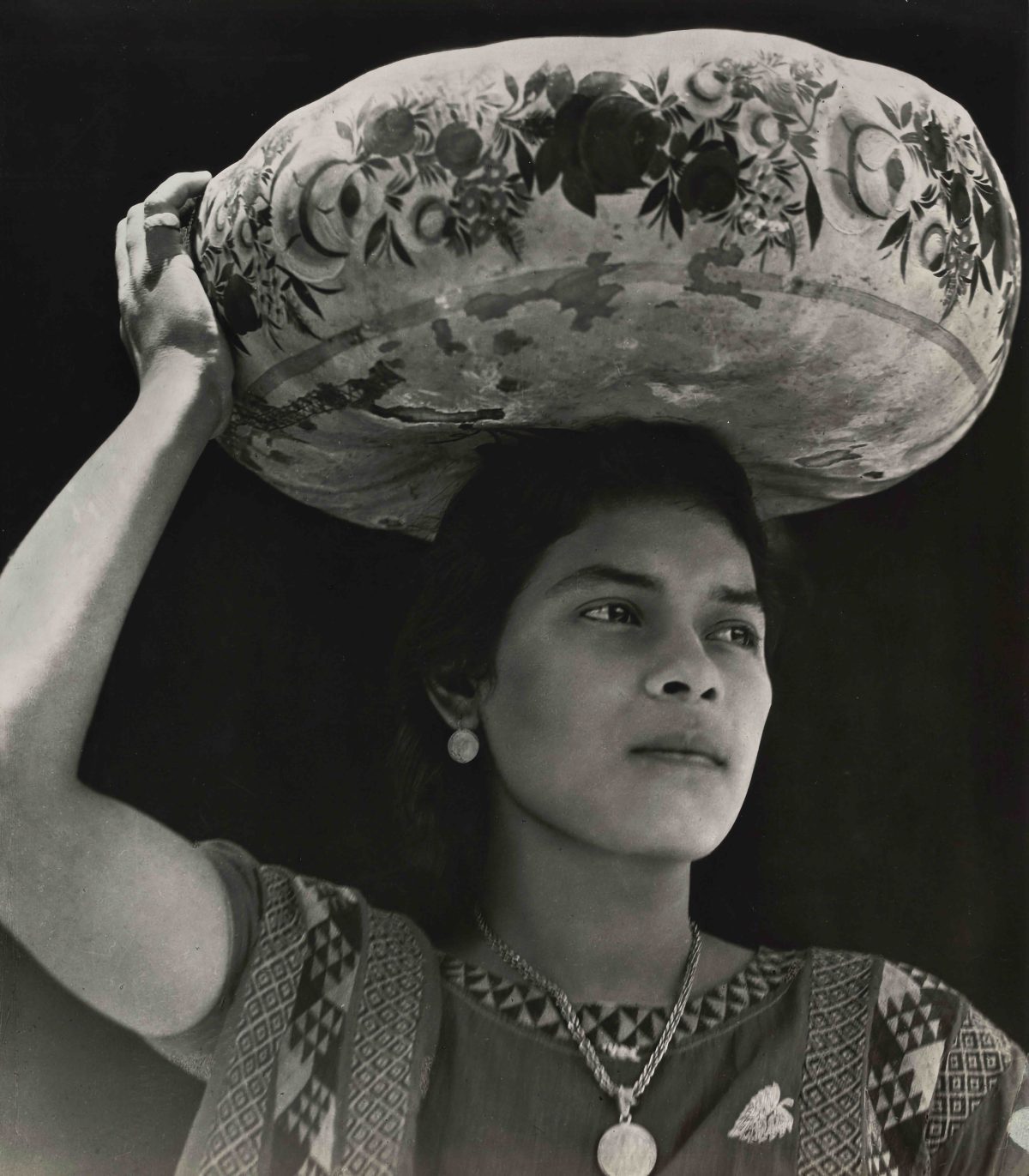

Tehuantepec Woman c. 1929 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

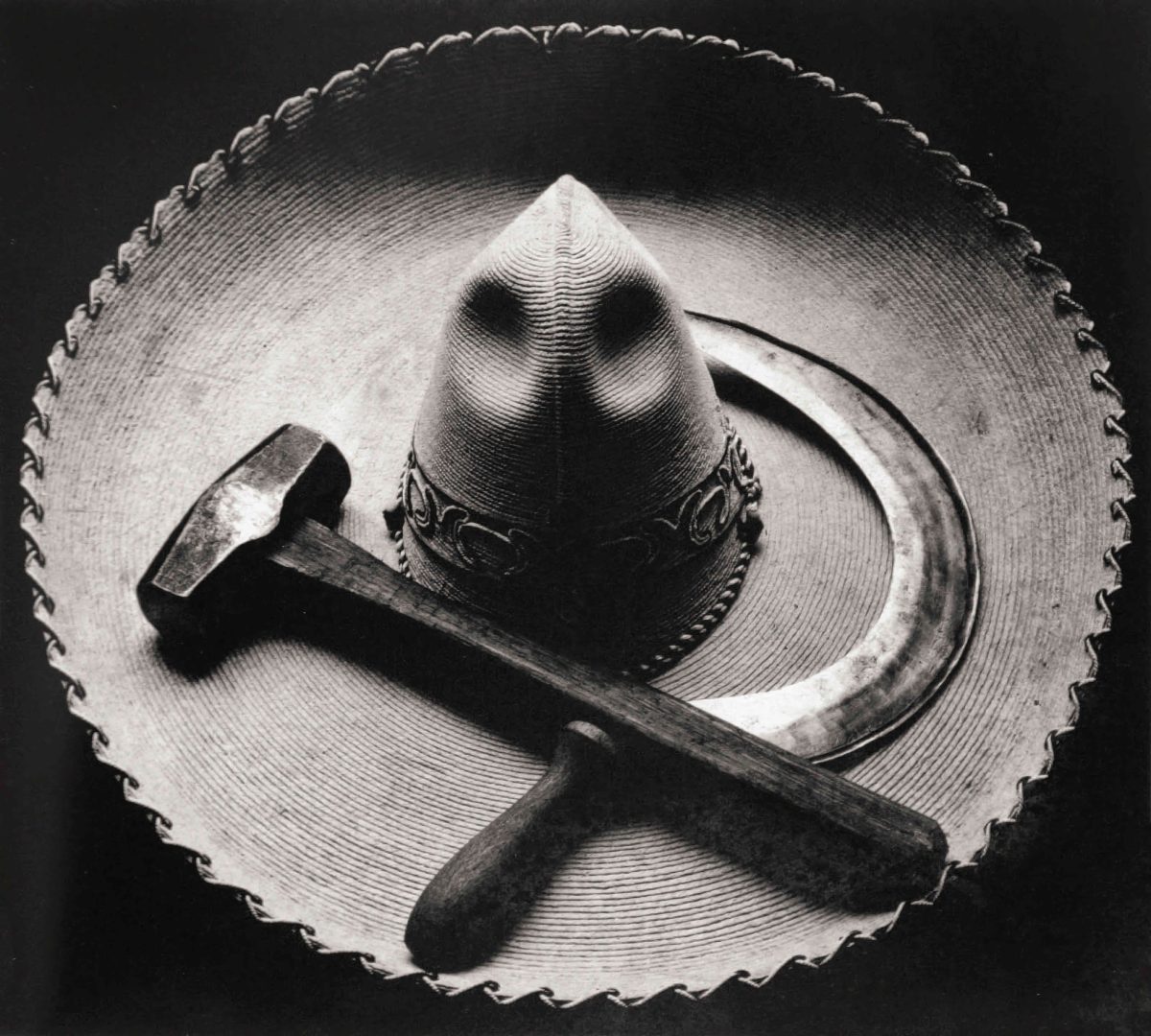

Sombrero, Hammer and Sickle, 1927 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

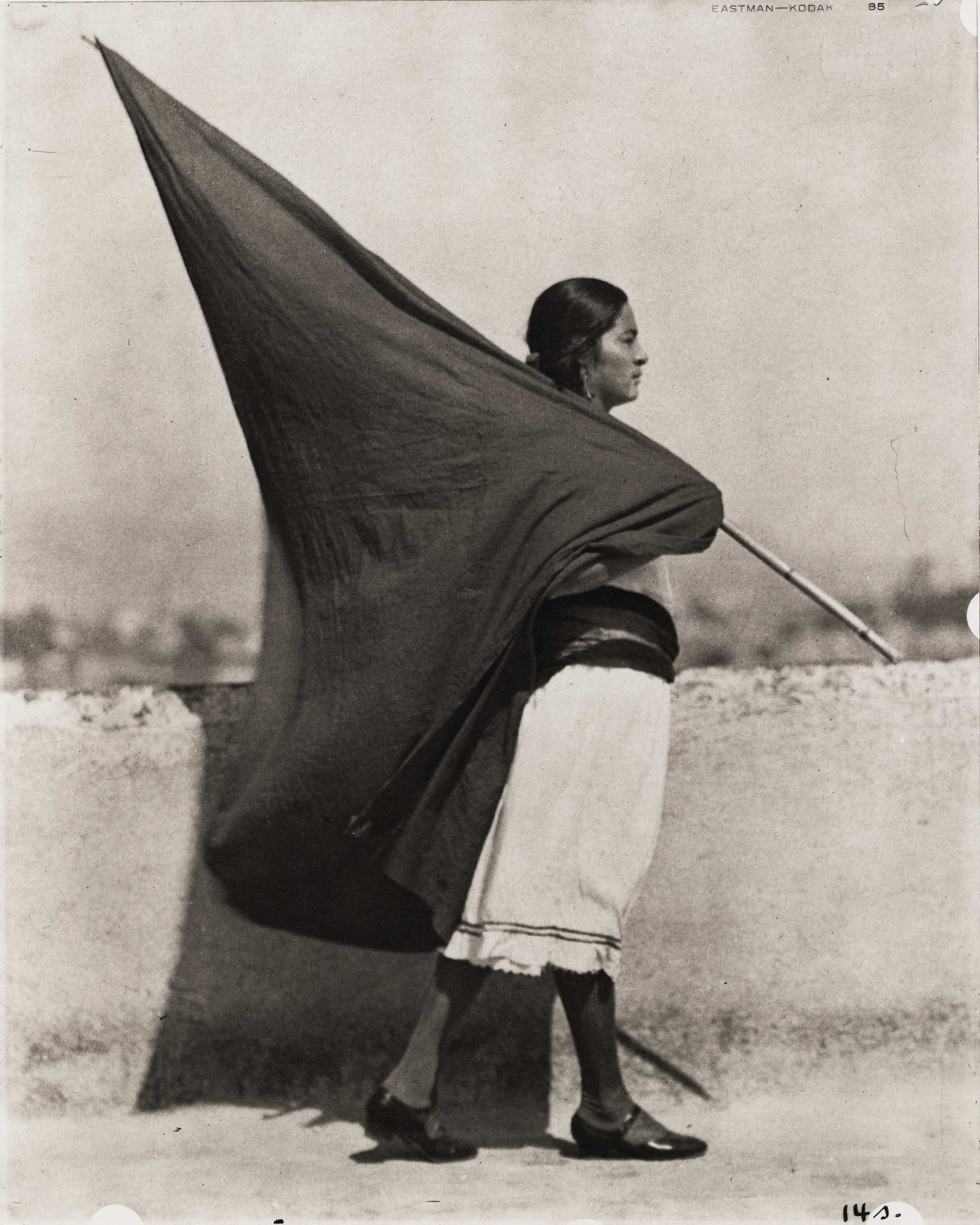

Woman with Flag, 1928 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

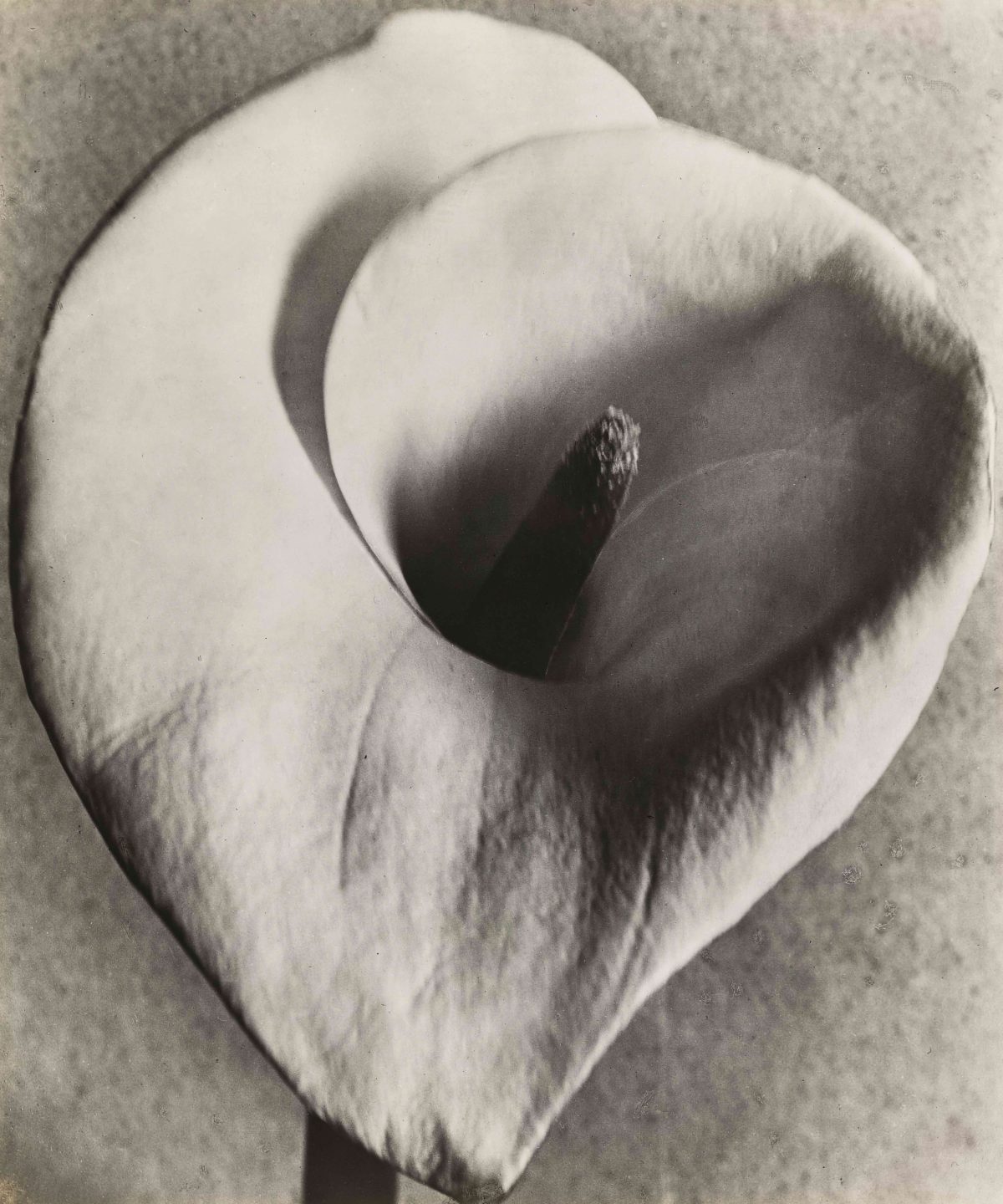

Roses, Mexico, 1924 – Buy Tina Modotti Prints

Buy Tina Modotti Prints & more in the Flashbak Shop.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.