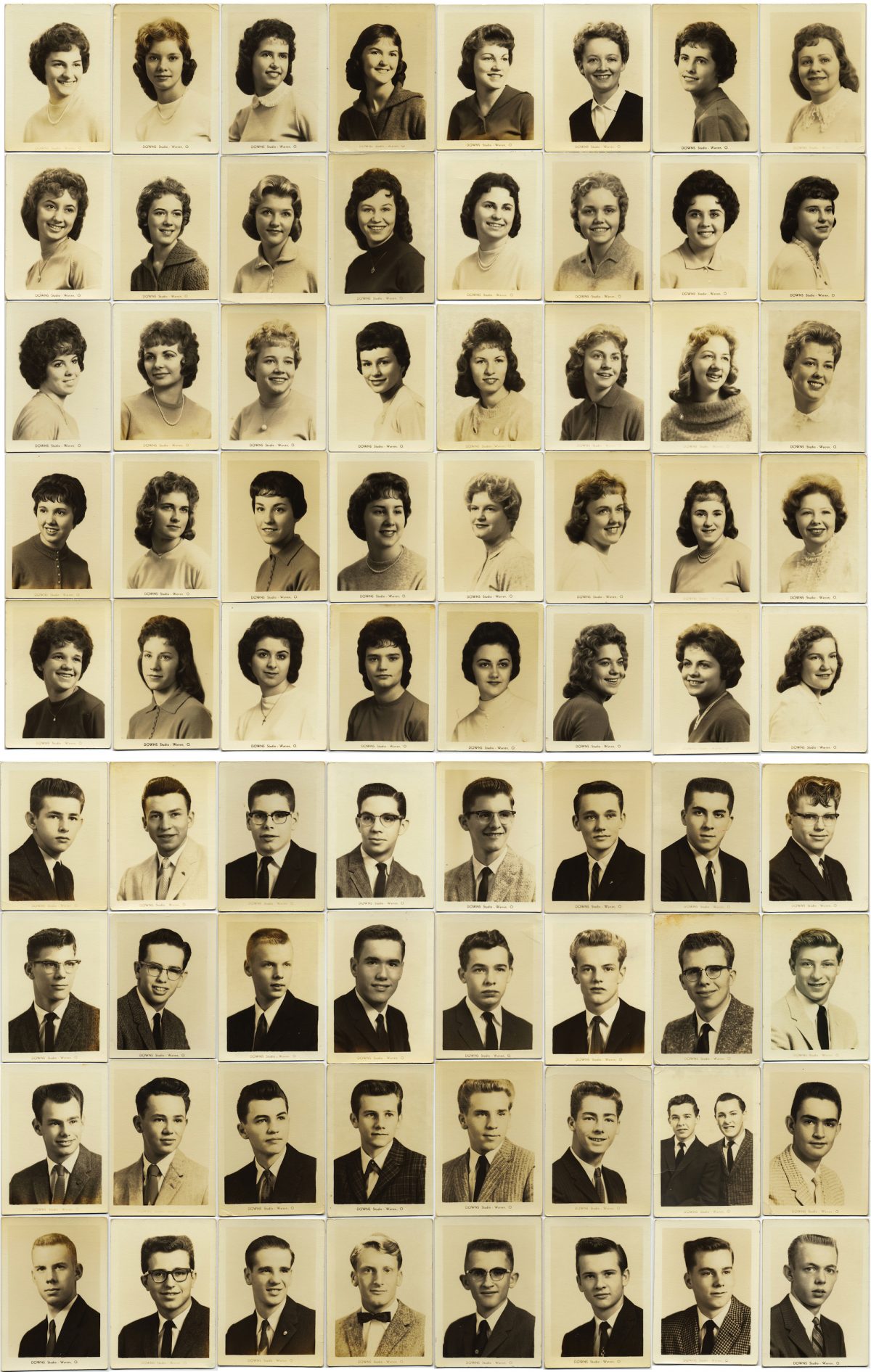

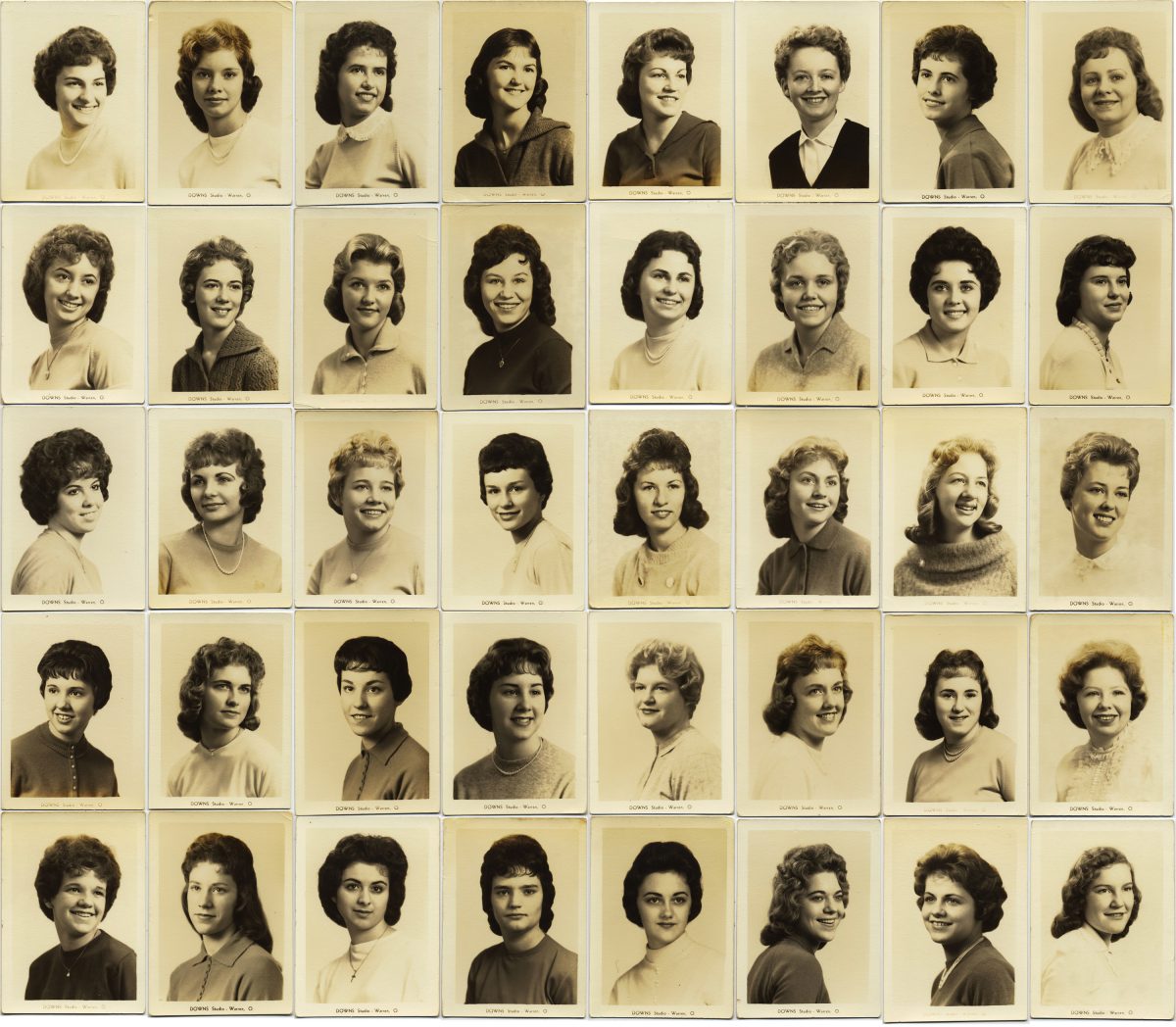

I somewhat recently purchased a group of yearbook photographs – 73 of them in all, and all relating to one graduating woman: Kay. Forty of the photos are of women; 33 are of men. The vast majority have dedicatory writing on the verso (and it was because of the versos that I bought the group). I thought it interesting to see what information and insights can be gleaned from these images, formulaic and unimaginatively conventional as they are. Certainly, the captions are the principal purveyor of content, but even without them, the photographer and/or the subjects make choices regarding self-presentation that reveal much about the times and more.

Let’s start at the beginning. Though we don’t know their exact provenance, it’s likely they came from the estate of the woman to whom they were originally given. We have enough information to know that that woman was “Kay” from Warren, Ohio. Warren, a small manufacturing town about half an hour by car from Youngstown, Ohio, and just over an hour from Cleveland and Akron, boasts Fox News’s Roger Ailes, filmmaker Chris Columbus, rock musician Dave Grohl, and a number of NFL players among its celebrated children.

Kay, we learn, graduated from Champion High School in Warren in the class of ’61 (she’d be around 75 years old today). Champion High had moved into a brand-new building just a few years before these photos were made. An online search reveals that Kay was, in all likelihood, Kay Jones. It’s not an unusual name, and since it is her maiden name, it’s difficult to find out much more about her (and especially what her life was like after Champion). But the information contained in the dedicatory notes on the versos of the images gives us a deceptively comprehensive picture.

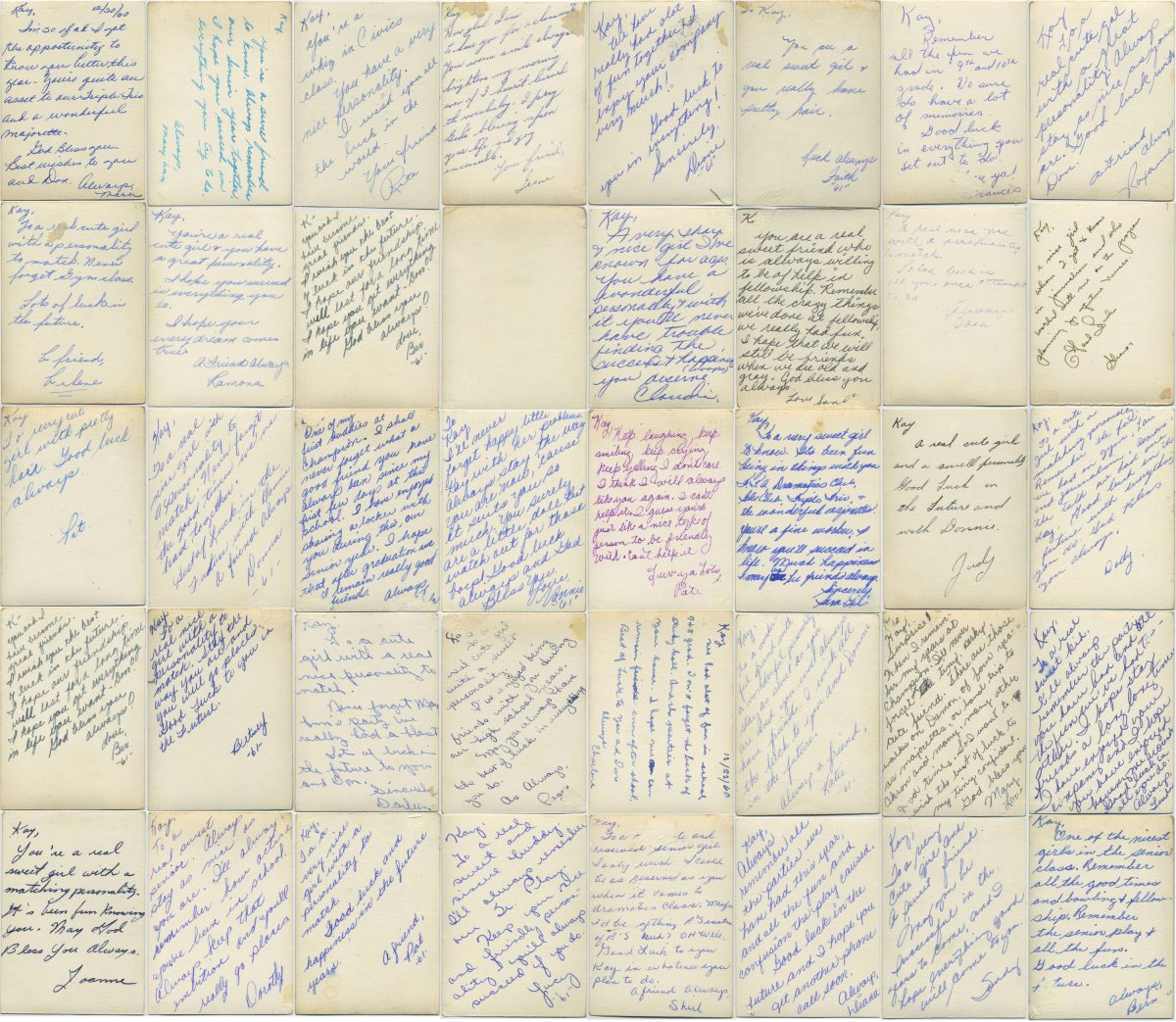

We discover that Kay was a “petite” woman. Her stature (“small”; “tiny”; “a doll”) was remarked on by more than one person, as was her hair (“pretty”). She seems to have been particularly adept physically as two women remark that they would “never forget gym class”. That this refers to physical ability (rather than a joking comment on ineptness) is supported by the fact that she also appears to have been a drum majorette (one assumes a level of physical dexterity and facility). Academically, Kay appears unremarkable, though she is once described as being a “civics class whiz”. Outside of that reference (and a couple of references to a journalism class) no other indication of academic or intellectual activities make their appearance in the comments.

Personality is where Kay excelled, and “nice” is by far the most common (and most anodyne) descriptor of it. “Cute” and “sweet” also make their appearances and how these three words break down in terms of sex is interesting. The men overwhelmingly use the adjective “nice” with twice the number of them (14) using it to women (7). When it comes to “cute” and “sweet,” however, only 1 man uses “cute” and only 2 use “sweet”- perhaps because those words have a more intimate and affective quality. Women are unsurprisingly more at ease with those terms, with “cute” edging out “sweet” 10 to 8 (the distribution of “cute,” “sweet,” and “nice” as descriptors is almost equally used among the women). While those adjectives usually qualify the word “girl” (as in “To a real nice girl”), frequently they are also tied to the linguistic formula: “To a real nice girl with a personality to match.”

The commonness of this formulation is notable, and when one thinks that each person might have had to write personal notes on 30 or more photographs of the graduating senior class, stock formulations are understandable. It should, perhaps, also be noted that, despite the regularity of this turn of phrase, significantly more women than men link “nice/cute/sweet” to personality (14 to 7). For men, “nice/cute/sweet” appears to encompass more than just personality. So Kay was seemingly well liked and popular (“friendly” is an adjective used frequently to describe her by both men and women), active (“the fun we had” is a common trope, though “clown[ing] around” also makes an appearance), and a few mention the “parties we had” as well as a “band trip to Akron” which was clearly memorable (at least to one respondent). She was outgoing and an extrovert. Outside of band and being a drum majorette, her most memorable activity was theatrical. A number of people mention her participation in “Dramatics Club” (and Glee Club) and especially the Senior play. This last theatrical venture was clearly memorable and caused “fun and confusion,” which leads us wanting to know exactly what transpired.

Only a few people hint at something perhaps a little more complex. One man mentions Kay’s “tough personality,” and a woman starts her dedication by saying “I’ll never forget happy little Kay with her problems” [emphasis added]. Another woman observes a rather ambivalent “Keep laughing, keep smiling, keep crying, keep yelling I don’t care. I think I will always like you again. I can’t help it.” A boy named Steve was perhaps a jilted suitor: “remember” he writes “when I liked you for a girlfriend? We surely had a lot of fun together. The very best of luck with ‘Peaner’,” he adds, jealously. It appears that “Peaner” is Don, Kay’s boyfriend (and, possibly, future husband). They were clearly a couple by the time graduation came around (he may have graduated before her). If so, the most likely candidate for “Don” is Donald “Don” Knowlton who graduated 3 years prior to Kay from Champion. Alternatively, one website gives Kay’s married name as Schultz, so a Don Schultz (or Someone Schultz) might have made an appearance in her life sometime after graduation. Whichever it was, it is very clear that Kay and Don were expected to marry and have a future together. One woman wishes Kay good luck for the future and hopes Kay “will get another phone call soon” which might refer to either theatrical or romantic developments. Either way, the relationship is mentioned in many of the dedications and is evenly split between men and women (8 women and 7 men mention Don or Donnie or Donny).

Finally, it should be noted that women wrote significantly more than men (1 woman wrote nothing; 3 men left their versos blank). The reasons for this might be various. Perhaps women felt more at ease writing to (and for) another woman? It is also likely that a young woman would have had more female friends or close acquaintances in high school than male friends. But it could also be the gender norms of the day might have discouraged male loquacity and imposed affinitive distance between the sexes. Additionally, there is notably little religiosity in the salutations. A few people wish Kay “God bless” (or variant), but the majority of well wishes are secular with “always” being the most common among the women and “good luck” (or variant) winning out among the men.

What is interesting, though, is that despite the brevity, stock formulations, superficiality of observation and remembrance, indeed despite the similarity of all the comments one to another, a remarkably full picture of the one woman we do not see depicted emerges. And although the brushstrokes of that portrait are broad, there is a surprising amount of texture to her biography.

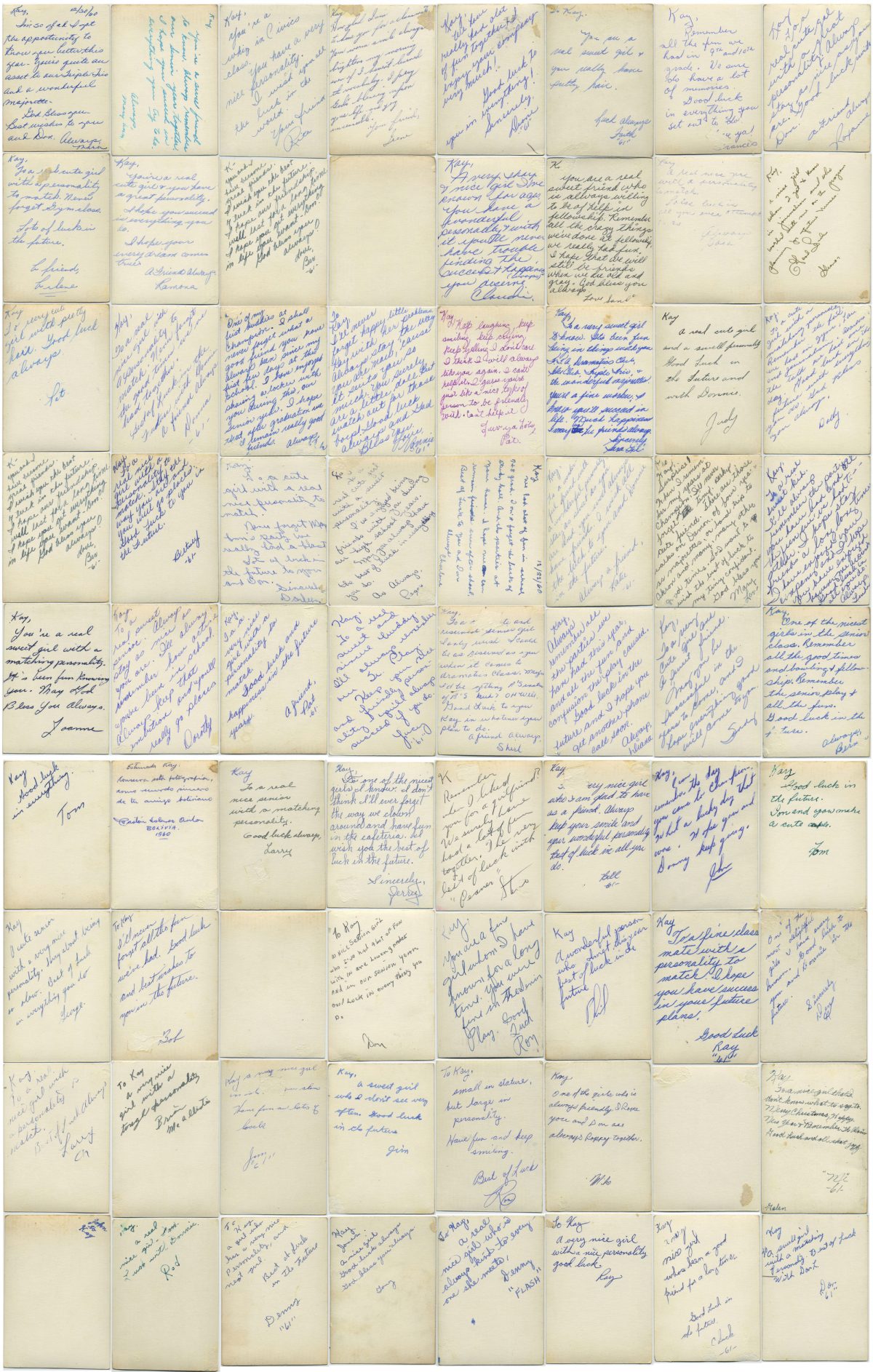

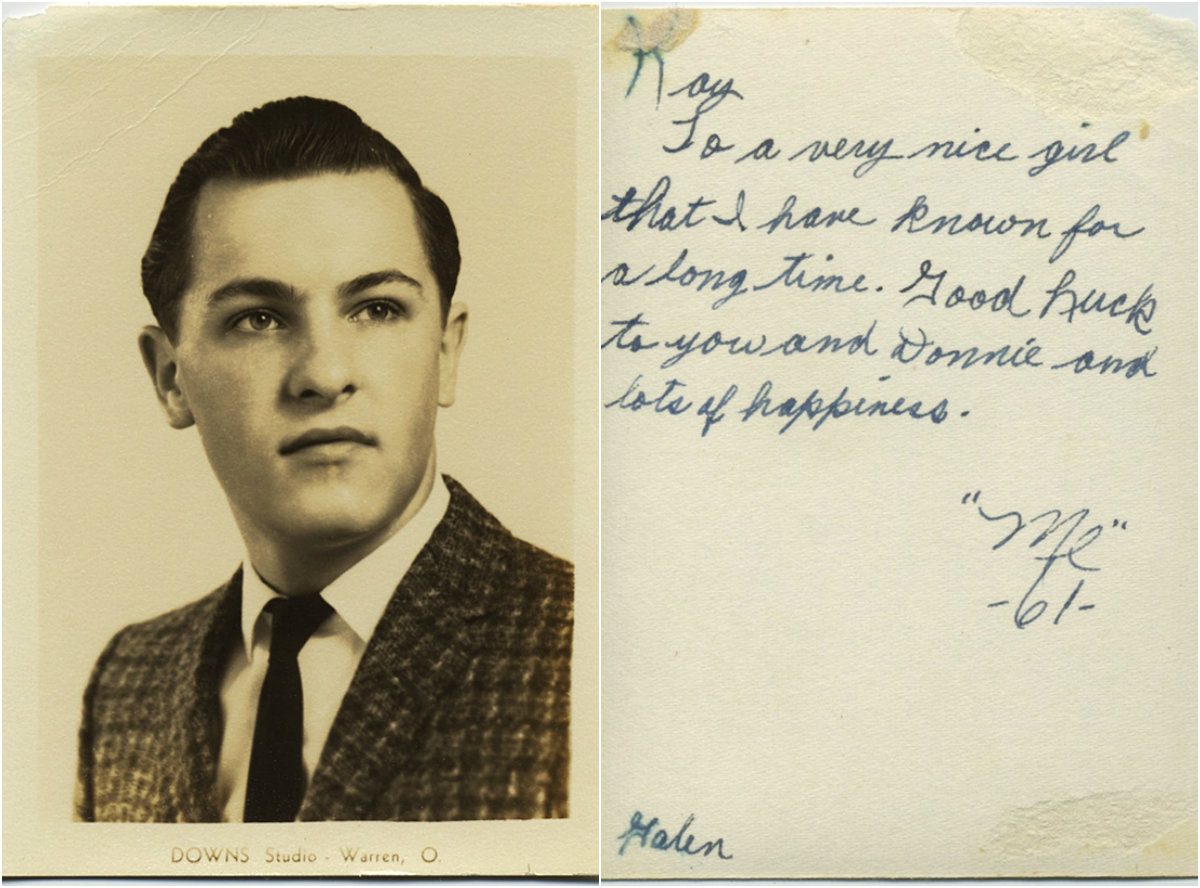

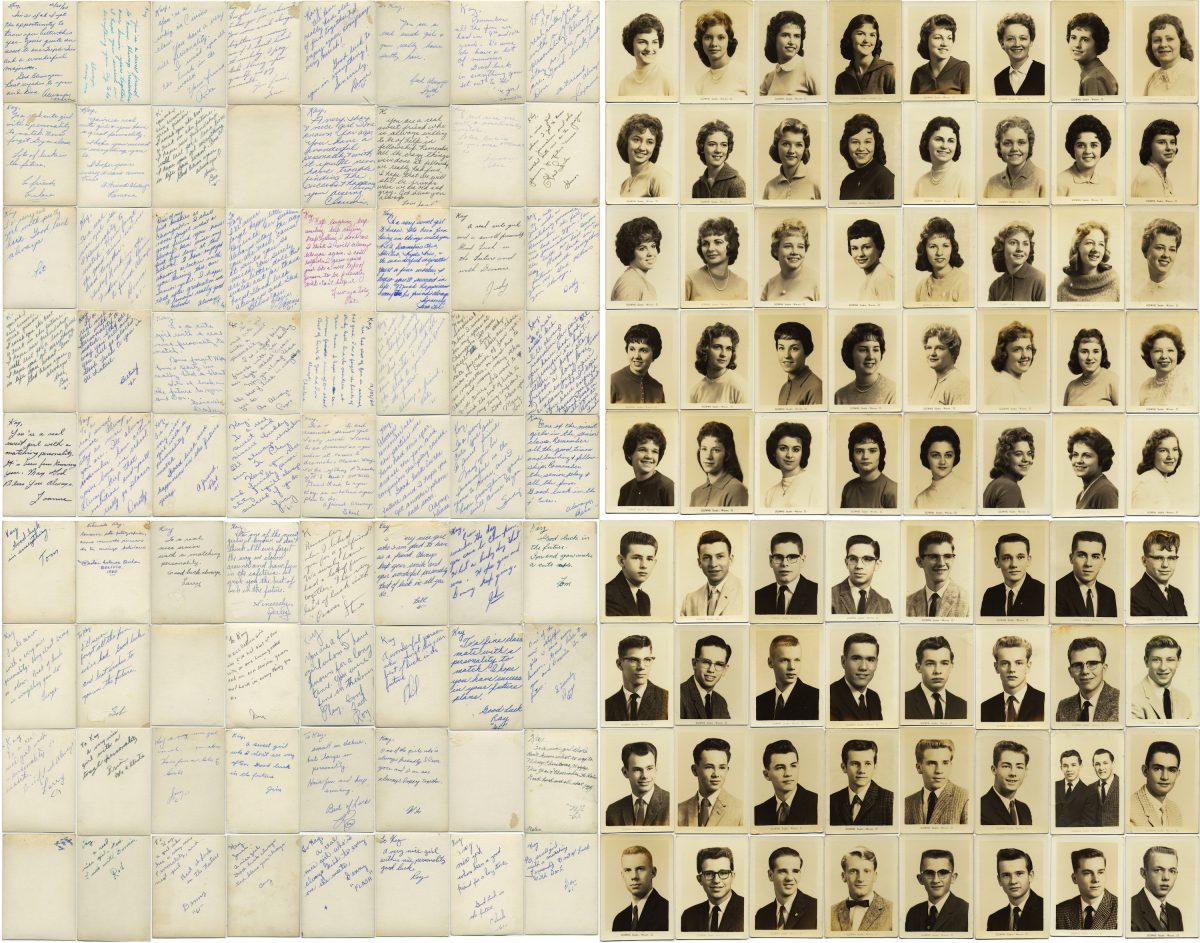

As mentioned earlier, what originally attracted me to this group of portraits was the writing on the versos.

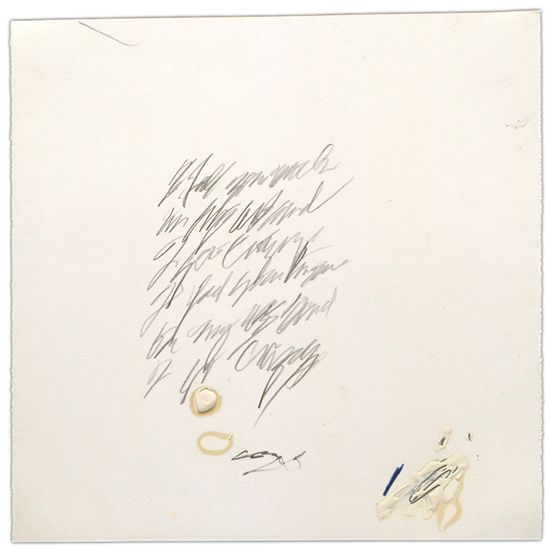

This and image below: Not quite Twombly-esque, (Cy Twombly, from Letter of Resignation) the different angles, inks, and density of the writings are visually compelling.

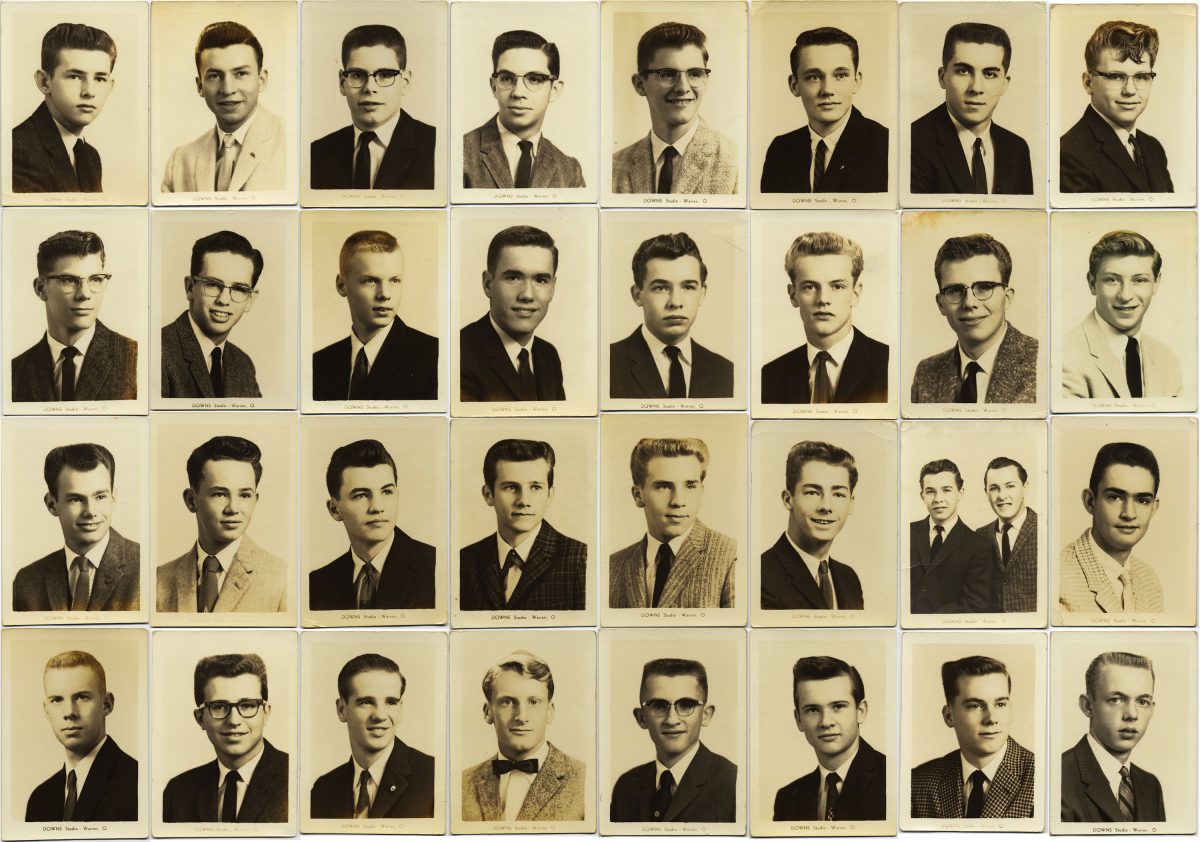

They form a gorgeous quilt of abstraction, pattern and texture when presented as a grid that feels incurably modern and quite contemporary. The way the texts nudge or push against one corner or edge, sometimes straining against the confines of their space, or the way some lines seem to cramp together or conversely to expand and breathe – the tension between negative and positive space; the way some lines curve and others adhere rigidly to an invisible grid, all lend the whole an undeniable visual rhythm. But equally, the amalgamation of those tiny messages to the future from (and about) the past are an intriguing and appealing conceit: were they cumulatively a portrait of an unseen woman? Or were they mini-portraits of the sensibilities of those depicted on their rectos?

The fronts of these photographic keepsakes also tell a story.

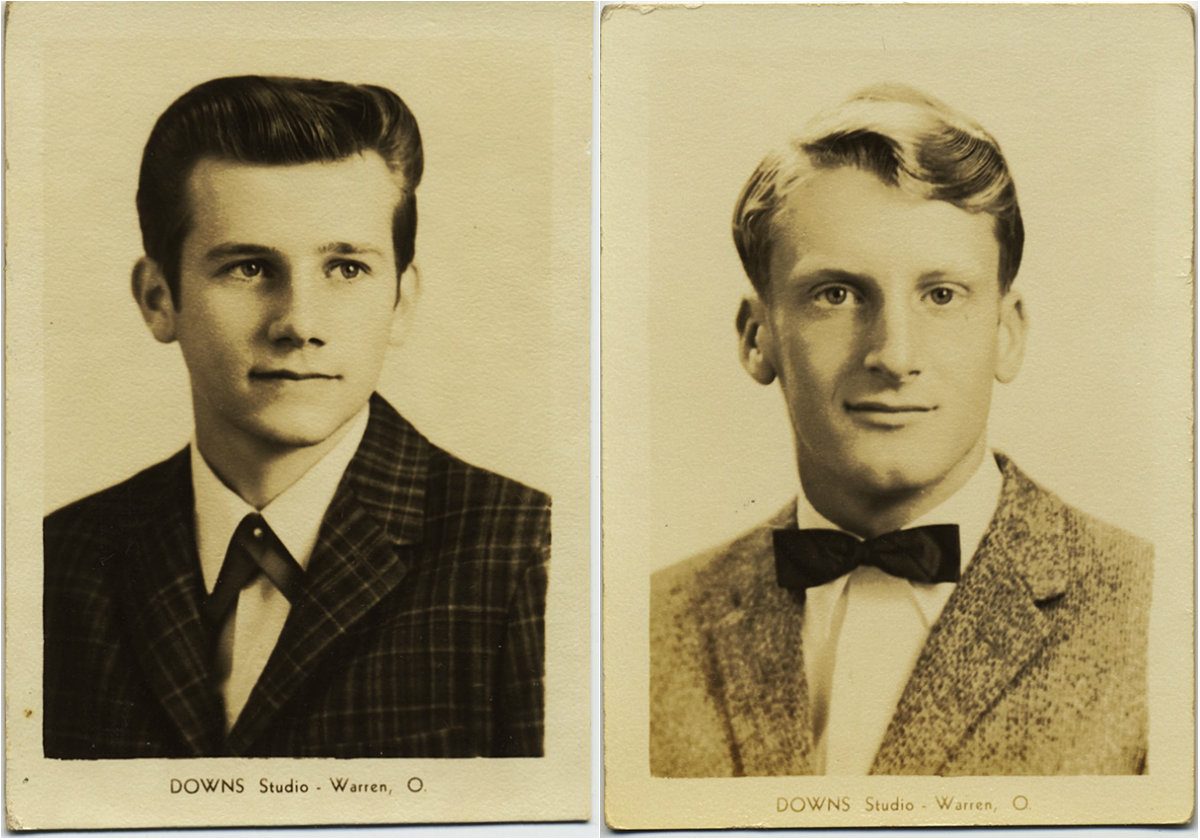

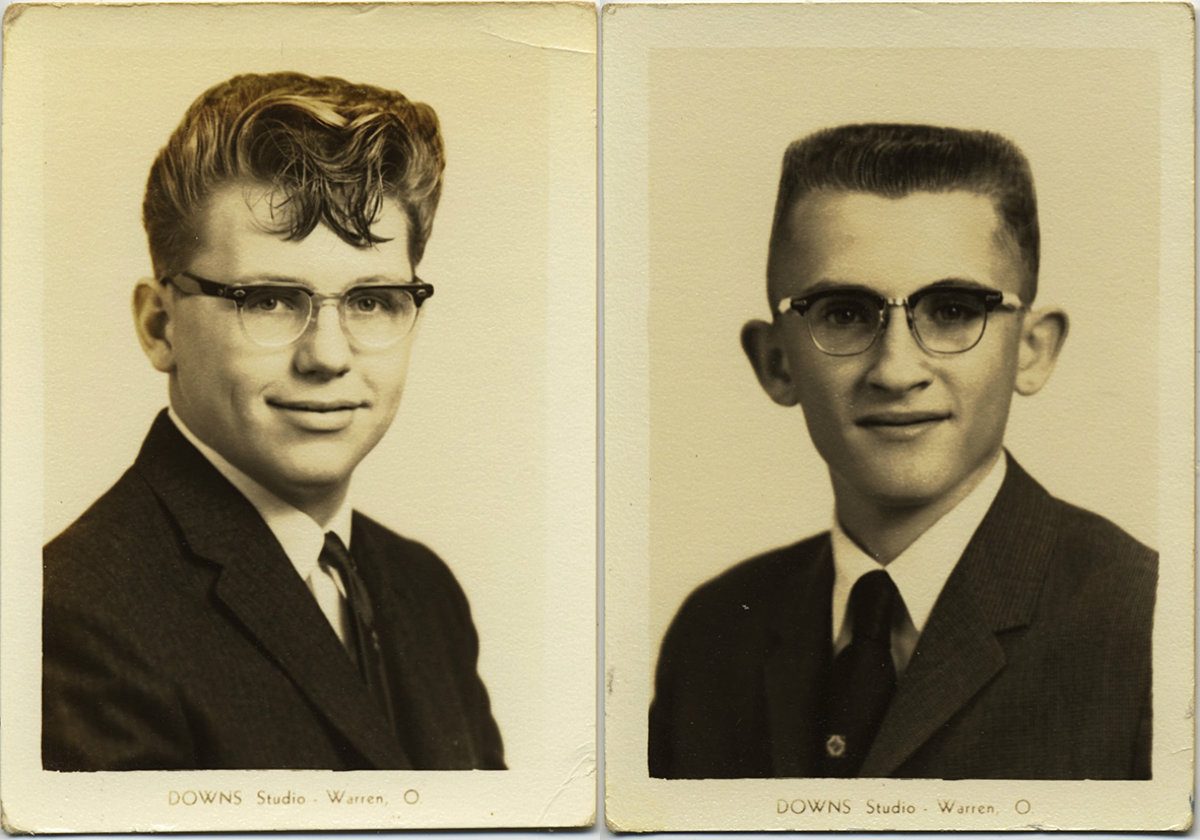

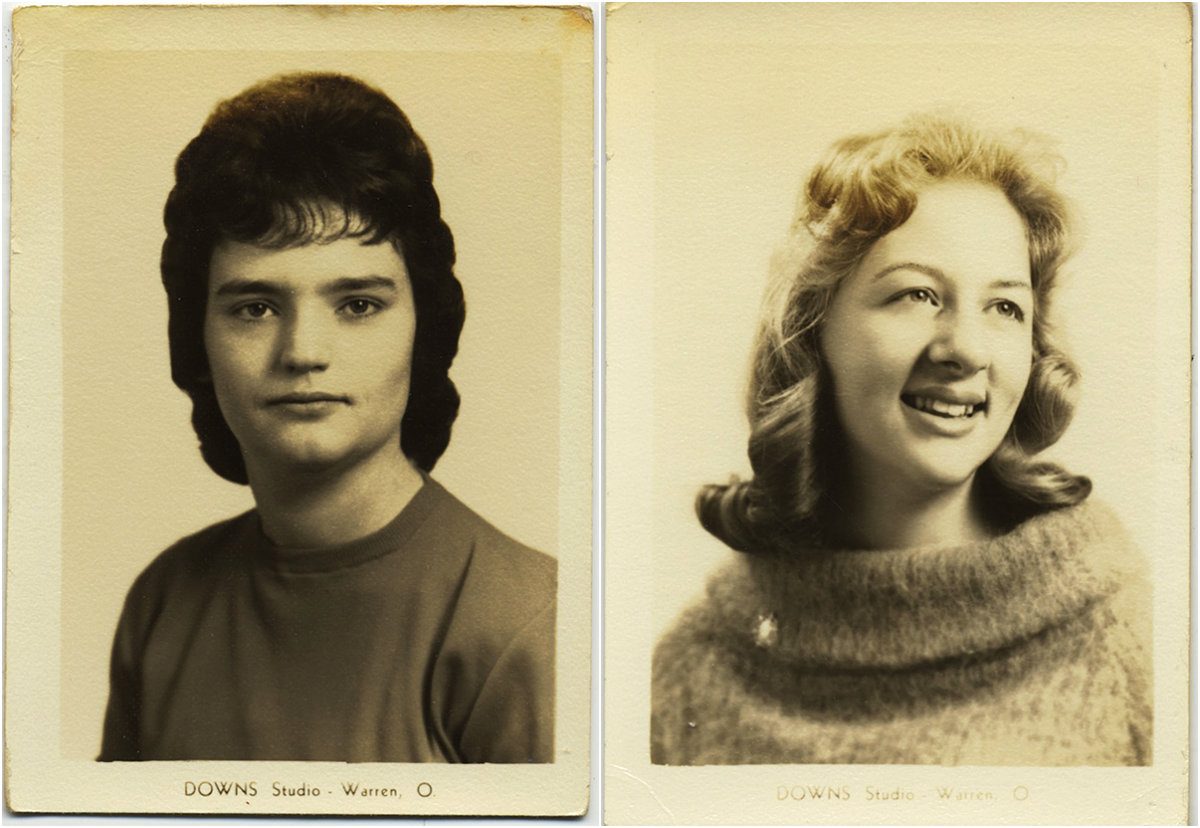

A longtime lover of photographs in series, I find the banality of these portraits—when viewed as a group—also immensely appealing. And banal they are chiefly because of their formal homogeneity: against a plain white backdrop, the students pose singularly (there is one anomaly: two men pose together in one image though the verso contains a note from only one of them). The men are all clean cut, suited and tie-d, mostly in dark colors (23, versus 5 in light colors, and 5 in textured or patterned/checked suiting). Only two men wear bow ties (one wears a western bow), none have facial hair of any type and only one wears his hair in any style other than off the forehead clear and clean. Of the nine who wear glasses, all but two wear browline frames.

This is an ostensible portrait of American masculinity at its most decorous, sedate, and suburban; conformity at its zenith. Yet these young Mid-Western men, presumably between the ages of 17 and 19 here, might soon – at the height of their early adulthood – be ensnared in the growing cataclysm of Vietnam or even, perhaps, abandon conformity altogether and immerse themselves in the counter-culture that the decade held in store.

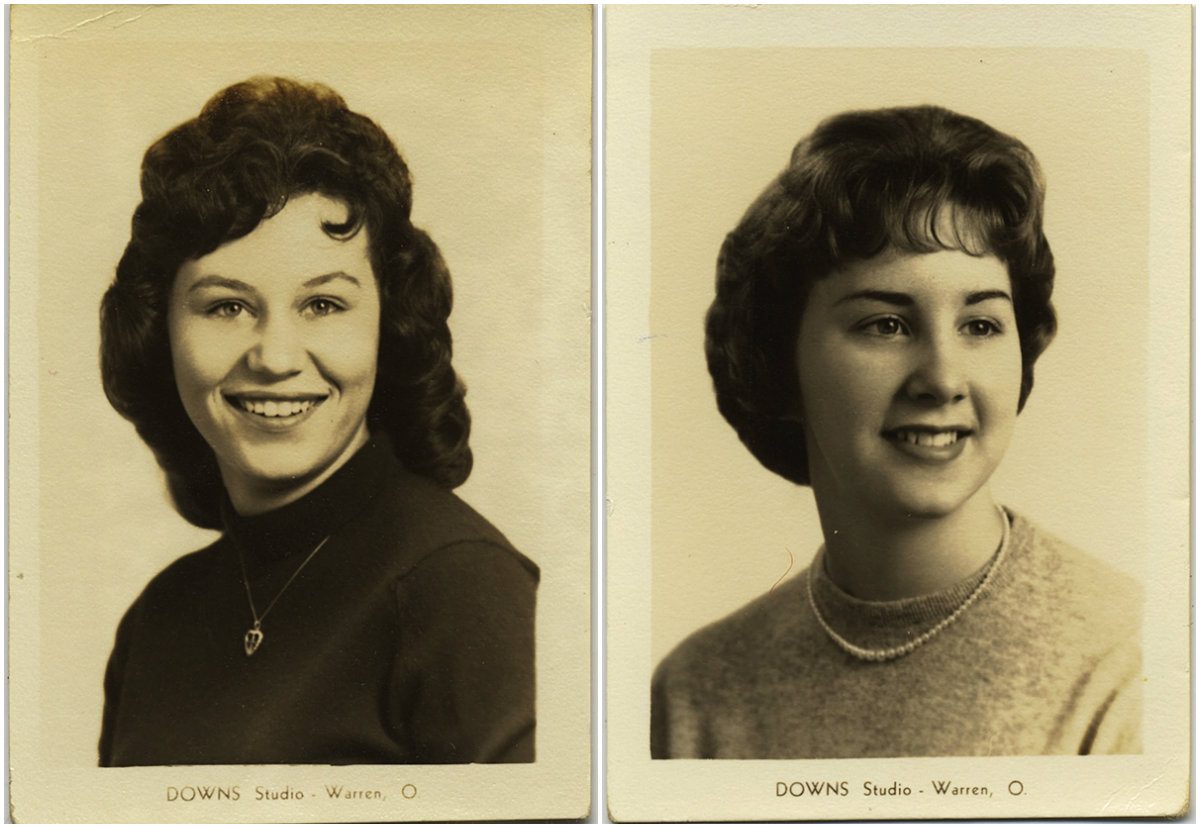

If the men dress mostly in dark colors, the plurality of women dress in light shades.

As with the men, decorum and propriety are the dress code of choice, collars define necklines and almost no skin below the neck is visible or even hinted at. Only in one case does a student opt for a softer neckline in the form of a sweater top (she is also the only woman wearing a pin or brooch, and one of the few whose hairline reaches the shoulders).

In terms of accessories, there are few, and they generally take the form of a small pendant on a chain (8 out of 40 women; only one woman sports a visible crucifix) or a string (or two) of pearls (5 out of 40 women).

The photographer of these portraits was Richard Downs. Downs – who had studied at the LA Arts Center for three years as a young man – was 37 when he shot these images (his studio had only been open for 3 years in 1961; it would stay open until he retired in 1987).

What is perhaps most interesting in these portraits is how Downs chose to pose his subjects and, especially, how the subjects’ focus and expression is sharply divided by sex. Though all the subjects’ torsos are at a slight angle to the camera (none face the camera squarely head-on) it is notable that 55% of the men look directly at the camera as opposed to only 25% of the women. The rest of the men look up and to the right (with a couple of outliers either looking above the camera or up and to the left). In contrast the majority of women look up and to the right with the rest either (as mentioned) staring at the camera, or up and to the left. Again, very few (5 out of 40) look above the camera. This directness of confrontation with the lens and photographer so evident in the men’s gazes is even more an indicator and delineator of gender roles when it comes to facial expression. While only 1 out of 40 women looks serious, 61% of men are serious in demeanor. 97% of women smile, either broadly (teeth visible) or demurely; only 39% of men do.

Here we see societal attitudes towards sex and gender expectations and roles most clearly delineated. While men are expected to both face the world and represent their personalities to it as direct, stoic, serious, and strong, women are clearly expected to be pleasing, amiable, welcoming, acquiescent, and unthreatening. These portraits express the roles these students (or the photographer) expected them to play in adult society at the very moment when they were about to enter into it.

But, as mentioned earlier, these images are taken on the cusp of a decade that would see immense societal change. (It is notable that despite the federal desegregation of schools in 1954, there are no minority students visible; there is one, visiting, Bolivian student. Warren, a factory town of about 60,000 people in 1960, was approximately 9% Black/African-American, at the time; it is 27% now.) It is difficult to imagine the staidness of these generic portraits reflecting much of what these young women or men would soon become in the years ahead of them as they moved through one of America’s most tumultuous decades. And what of Kay, the diminutive, friendly girl, with that nice personality and looks, good at dramatics, drum majoretting, and civics, with pretty hair, soon to be married to Don? We can imagine her own photo and dedication looking very much like those that were given as keepsakes to her. Indeed, looking through yearbook pictures, the only pictures that appear to be of Kay show a young woman remarkably like her peers.

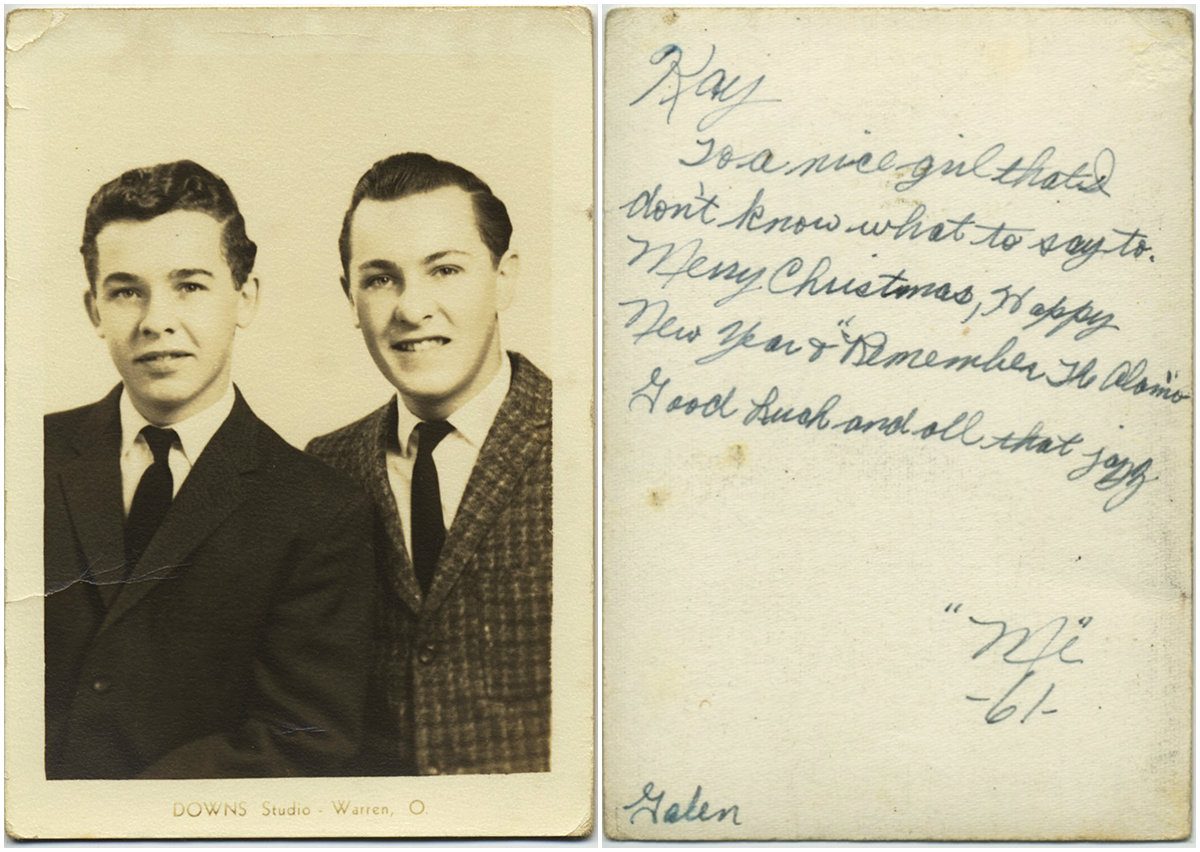

The two most common tropes about photography are that “a picture paints (or is worth) a thousand words” and that photography can either “steal” the soul of the portrait sitter or somehow reflect the soul in a direct and uncannily accurate way. Do either of these tropes apply to these photos? Barring the photo of the young man with the (more fashionable?) hairstyle (shown above) it is difficult to look at the photographs of any of these students and perceive an individuality – let alone any soul-stealing – straining to escape the straitjacket of conformity. Most of these students look like “nice” men and women with “personalities to match.” Indeed, if there is any attempt at originality, it is reflected in the dedications on the versos. Remember the anomaly mentioned above of the two guys sharing one photo? Well, it turns out that there is an image of one of those guys by himself, but I’ve not included it in the grid of men posted above (there were 33 men; the grid shows only 32).

On the rear of his solo pic, Galen (for that’s his name) writes: Kay / To a very nice girl that I have known for a long time. Good Luck to you and Donnie and lots of happiness. / “Me” / -61- But on the rear of his duo shot, he writes an almost contradictory: Kay / To a nice girl that I don’t know what to say to. Merry Christmas, Happy New Year & Remember the Alamo. Good Luck and all that jazz / “Me” / -61- . Could Galen have been another disappointed suitor? Who is the boy with whom he is posed? Why the tonal difference between the two dedications (“Good luck to you and Donnie…” versus “Good Luck and all that jazz”)? Why the “Me” in quotes, yet the insurance policy against the erasure of memory—the hand-written “Galen”—at the cards’ bottoms? Either way, the brief flash of humor is both welcome and unusual in the dedications.

Though the pictures provide very little information about those depicted (one might be hard pressed to say they paint even 100 words), the dedicatory words supply at least some of what’s missing. But, in another sense, one might also say that the reverse is true: that the rote-ness and formulaic mundanity of the written dedications paint a fairly exact picture of that perfectly adequate and perfectly nice graduating woman named Kay Jones who looks perfectly like almost everyone else in her graduating class. And one might even go further and suggest that, in some sense, the images (perhaps perversely) do paint 1000 words. But these are not words about the women and men depicted, but about the very place and purpose that those young people were scheduled, groomed, and supposed to fill in the American dreamland of the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. It was a place that would turn out to be not as standard and idyllic as the flawless, homogenous images suggest, but rife with societal, racial, sexual, and generational conflict that would render the vision these class photos present redundant or outmoded sooner than the subjects themselves might possibly have guessed.

But what did we expect? These are yearbook photos after all. They are keepsakes, at best to be kept in a purse or wallet, tossed in a drawer, tucked between the pages of a book; perhaps the modern version of a carte-de visite. Though the idea of a yearbook might go back to scrapbooks from the 17th century, the 20th century version, according to the website of a yearbook publisher, dates from the 19th:

It wasn’t until 1806 that the first college yearbook was published, by Yale University. Eighteen years later, in 1823, the Massachusetts College of Pharmacy published the longest surviving book, entitled the Signia. It was 22 years after this, that the first high school yearbook was published. This book was called The Evergreen. The printed books we know and appreciate today, came to exist in the 1880s … People were able to mass produce yearbooks and make the printing easier and faster.

These headshots functioned as cast lists for the Senior class, a visual rollcall of participants in the lives and activities laid out in those annual summations. Like all “functional” photography (my term for what we generally call the “vernacular”), their function is to document, not to describe; to serve as an impartial visual fact—or as close to that as the combination of human being and photographic depiction can get. They describe a summation of physical characteristics, without describing character. In this, these images can barely be termed “portraits;” they are identifying markers for the memory of she to whom they were given; they are secular totems, not of a personality, but of the idea of young American adulthood, ostensibly bound for a particular kind of success, in a particular kind of role, in a particular kind of world. As we were to discover later in the 60s, that kind of world was a fiction. But just as these images fail at being “fact,” they fail equally at representing the “real.” They are themselves fiction; there to represent both a sanitized ideal and an aspirational dream of a future that had never existed and possibly could never exist.

These images also exist at a watershed in time, the cusp of the past (this is a remembrance of who we were as the high school students you may have known) and the future (this is who we believe ourselves to be in the future we envisage/wish/hope for). What the images do not exist in is the present: this is who we are. To be in the present, even the present of 1961, they would have to reveal. Instead they mask; they hide behind both the presentational look each student chose to put forward to the camera and by the photographic structure of class yearbook portraiture. Downs, the photographer, had neither the skill nor the desire (nor the mandate) to describe the individual. Instead, the men and women in these pictures are interchangeable and indistinguishable one from the other. Their only hope of individualized redemption are those few words scribbled on the back—those largely formulaic remembrances, paeans to friendship, hopes and good wishes for the future, shards of memories intended to recall or evoke. Viewed together, those scribblings provide not only the greatest visual interest, but they also act as a composite image of the woman to whom they are addressed and as the most delicate of filaments: tendrils of memory and emissaries of meaning from the past, desperately hoping to link the bloodless images on their rectos to a future still to come.

Follow Nigel on his website , at foundphotographs.com and on Facebook.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.