‘I came out with a towel around me looking for the mail and there was Sophia Loren. And she said to me, “Tony Vaccaro, always ready. Sempre pronto.’

– Tony Vaccaro

It may seem odd that a traumatized war photographer who trained his lens on the grimmest scenes imaginable should turn to fashion and celebrity on his return home. (Or, in the case of Lee Miller and Cecil Beaton, should move in the opposite direction.) On the other hand, it’s easy to see exactly why a war photographer would never want to see another immolated corpse or a village reduced to rubble. What could be farther from the battlefield than the world of haute couture? In the case of Tony Vaccaro, there is far more to say about his move from one to the other.

Born in Pennsylvania, he moved to Italy at an early age, his family on the run from the mafia. Both parents then died by the time he reached age 5. Despite these early traumas, he was determined to become an artist and he always treated his fashion photography as art. He would go on to photograph Jackson Pollock, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Marcel Duchamp. In a shoot with Pablo Picasso, he pretended the camera had broken. “He kept posing like male models,” he says. “I wanted real photography to be real photography. Honest photography.”

Hubert de Givenchy and Eartha Kitt, 1961 by Tony Vaccaro

He photographed on the set of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and captured movie stars like Sophia Lauren and Eartha Kitt in “honest” poses and moments. And he brought the same approach to his fashion work for Life, Look, Harper’s Bazaar, Newsweek, and more as he tells Rachel Gould at Culture Trip:

“I had models running through the streets, and I took many photos while the models weren’t expecting it. Over time I was able to remove anything artificial – even poses. I put my subjects in an environment – their favorite environment – and then I took photos.”

This shift is evident in his 1960s color work and his sometimes even psychedelic collaborations Finnish brand Marimekko, in which he occasionally uses multiple exposures, the kind of effect he otherwise strenuously avoids.

Georgia O’Keeffe by Tony Vaccero in 1960 – Via

Vaccero’s incredible life story contextualizes his fashion work. Photography at first, for him, was a means of surviving a war he fought as an “infantryman in the 83rd Infantry Division,” that landed on Omaha Beach, The Eye of Photography notes, “six days after the first landings at Normandy. Denied access to the Signal Corps, Tony was determined to photograph the war, and had his portable 35mm Argus C-3 with him from the start. For the next 272 days he photographed his personal witness to the brutality of the war.”

Vaccaro developed his own negatives in foxholes at night, pouring chemicals into helmets and hanging the prints on branches to dry. The experience of war was thoroughly scarring. “I was evil for 272 days, but not forever,” he says near the end of Underfire, an HBO documentary about his life. “I realized he was suffering his entire life, as many vets have, from PTSD,” says filmmaker Max Lewkowicz. “It’s the story of a real human being who’s cast into a world of horror, but besides having to live with it like most soldiers do, he also had this incredible drive as an artist to photograph it.”

He took a total of 8,000 war photographs, and most of them remained unseen until the 1990s. “He was not known at all as a conflict photographer,” Lewkowicz says. But his work did appear in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes, where it attracted attention. His touching photo The Kiss of Liberation became world famous. Most of his WWII photographs captured darker scenes, such as the award-winning White Death, depicting the blackened corpse of Private Henry Irving Tannenbaum, lying dead in a snowy Belgian field that had been used for growing Christmas trees.

This bleakley ironic photo would launch Vaccarro’s career in fashion. “When the editor of Flair magazine, Fleur Cowles, asked me if I can do fashion this way, looking at White Death,” Vaccaro remembers, “I said to her, yes I can. I had never photographed fashion in my life.” He may not have had the same motivation as when he was a DIY photojournalist during the war, when, he says, “I knew I had an opportunity to tell the future what was happening now. I had run away from fascist Italy in 1939, so I knew how fascism was ruining lives.”

Tony Vaccaro, :PVT Henry I Tannenbaum Ottre Belgium, 1945. Buy prints of this and more of his images at the Monroe Gallery

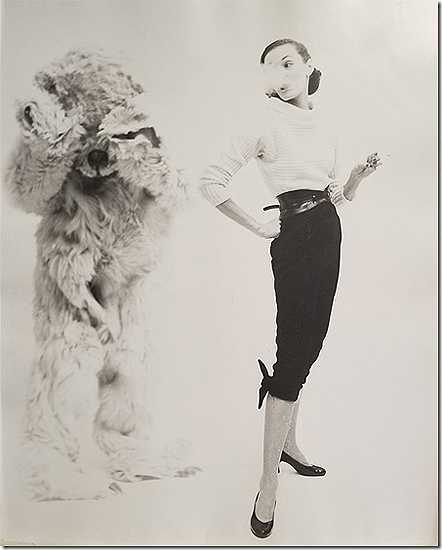

Model and Bear for LOOK, 1950

But whether as documentarian, artist, or commercial photographer, Vaccaro is most of all extraordinarily persistent. He is “one of the few people alive who can claim to have survived the Battle of Normandy and COVID-19,” which he contracted at the age of 97 and from which he almost immediately recovered. “I really feel I have luck on my back,” the almost-98-year-old photographer says. “And I could go anywhere on this Earth and survive it.”

The Sun, LOOK, NYC, 1969

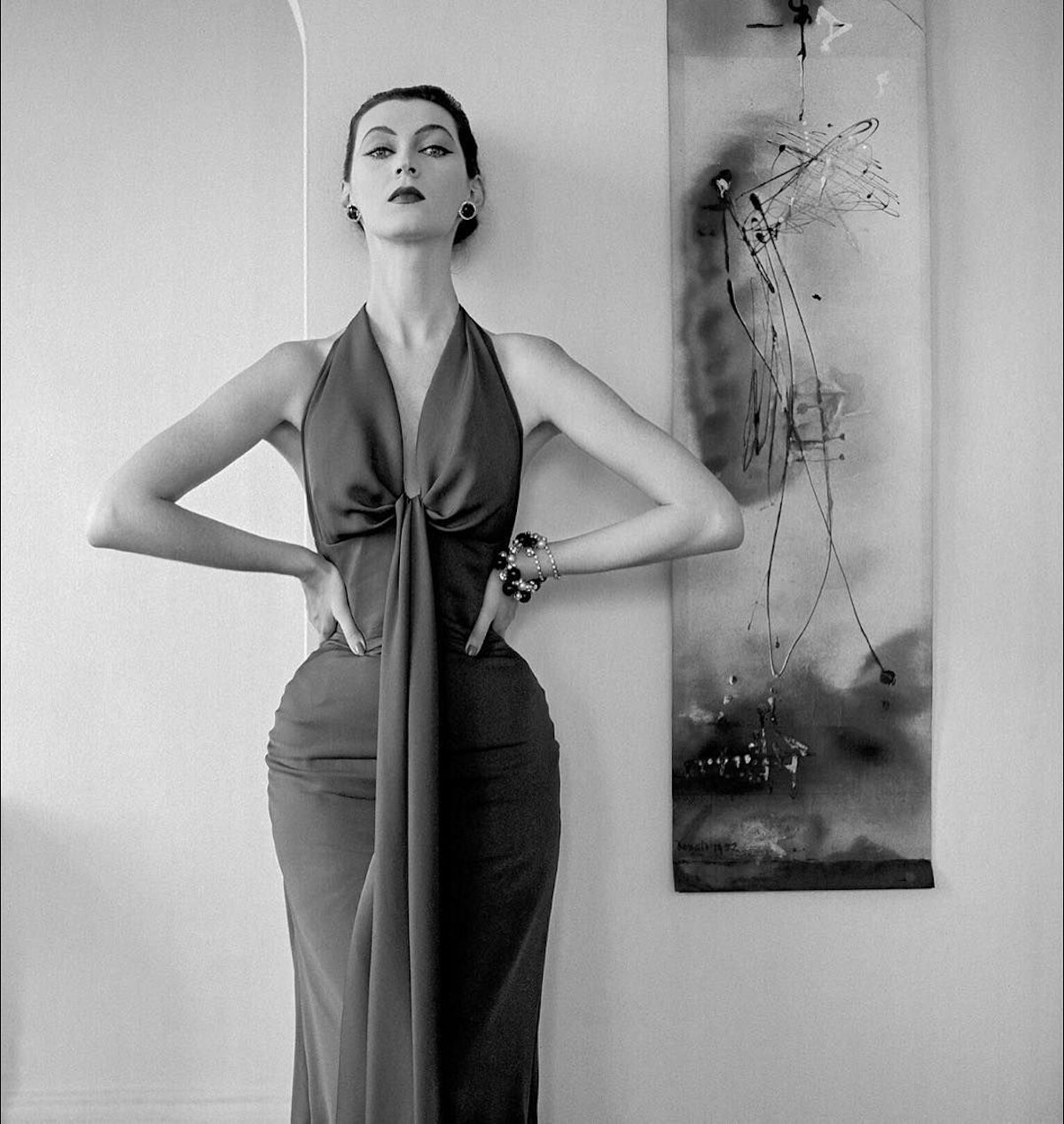

Lead image: Gwen Verdon, New York City, NY, 1953.

Via: Tony Vaccaro: From Shadow to Light will run at Getty Images Gallery, Library of Congress, Monroe Gallery, LadyWorld

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.