Waves Like Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night: Horio Mosuke Yoshiharu and the Flooding of Takamatsu Castle, sheet of a triptych

Edo, ninth month 1865 Utagawa Yoshifuji (1828 – 1904)

Vincent van Gogh (30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) moved from Paris to Arles in the south of France in search of the “clearness of the atmosphere and the gay colour effects” he saw in his collection of Japanese prints. He wrote that Japanese art made him happy and cheerful. He made three paintings after Japanese prints from his own collection. This gave him a chance to explore the Japanese printmakers’ style and use of colour.

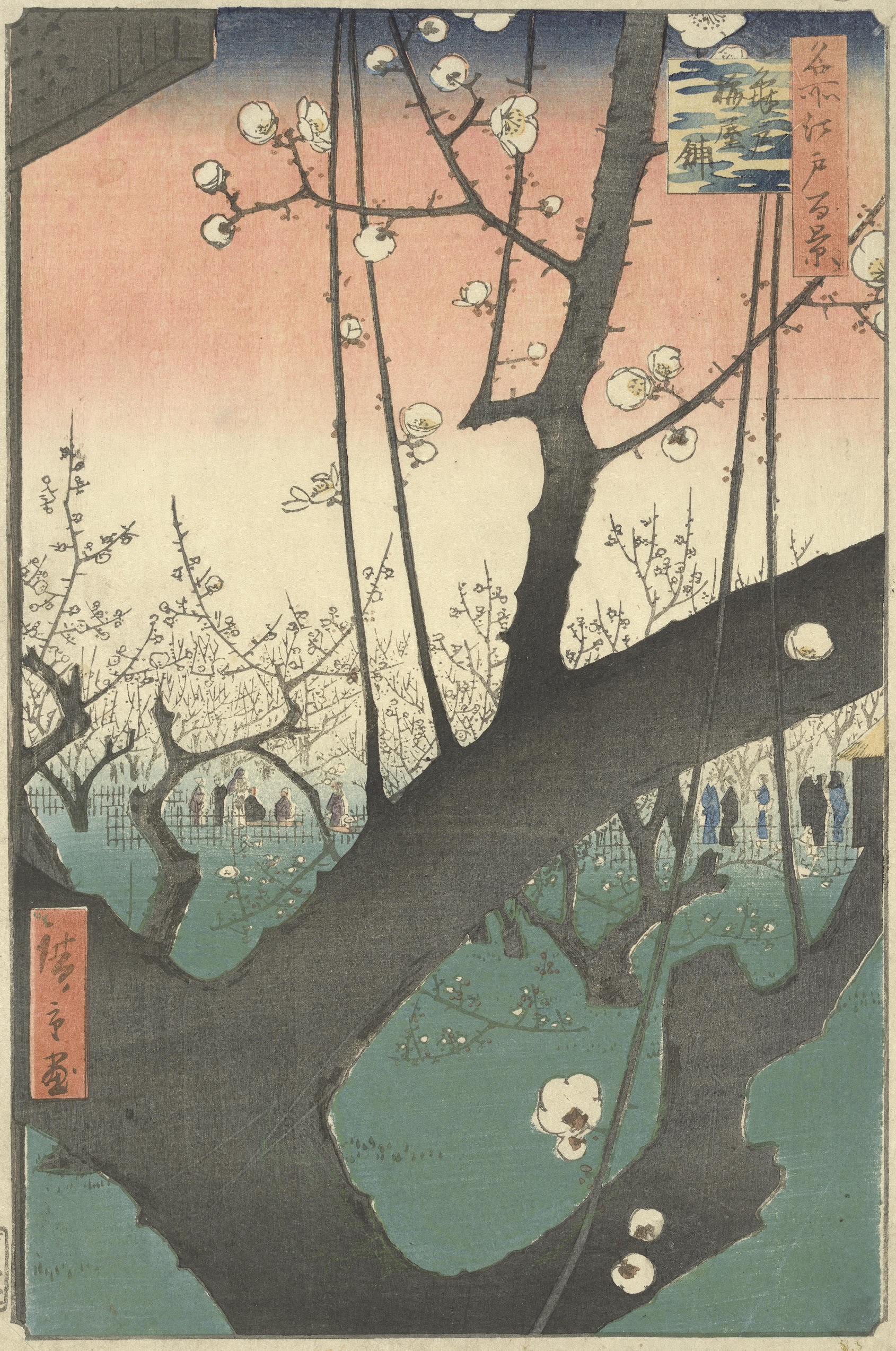

As the Van Gogh Museum tells us: The first of these copies is based on Utagawa Hiroshige’s Plum Garden in Kameido. Van Gogh accurately reproduced the composition but made the colours much more intense. He replaced the black and grey of Hiroshige’s tree trunk with red and blue tones. He also added the two orange borders with Japanese characters for a decorative and exotic effect. The original and Van Gogh’s copy are in the next three images:

The Residence with Plum Trees at Kameido, from the series One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo

Edo, eleventh month 1857 Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858)

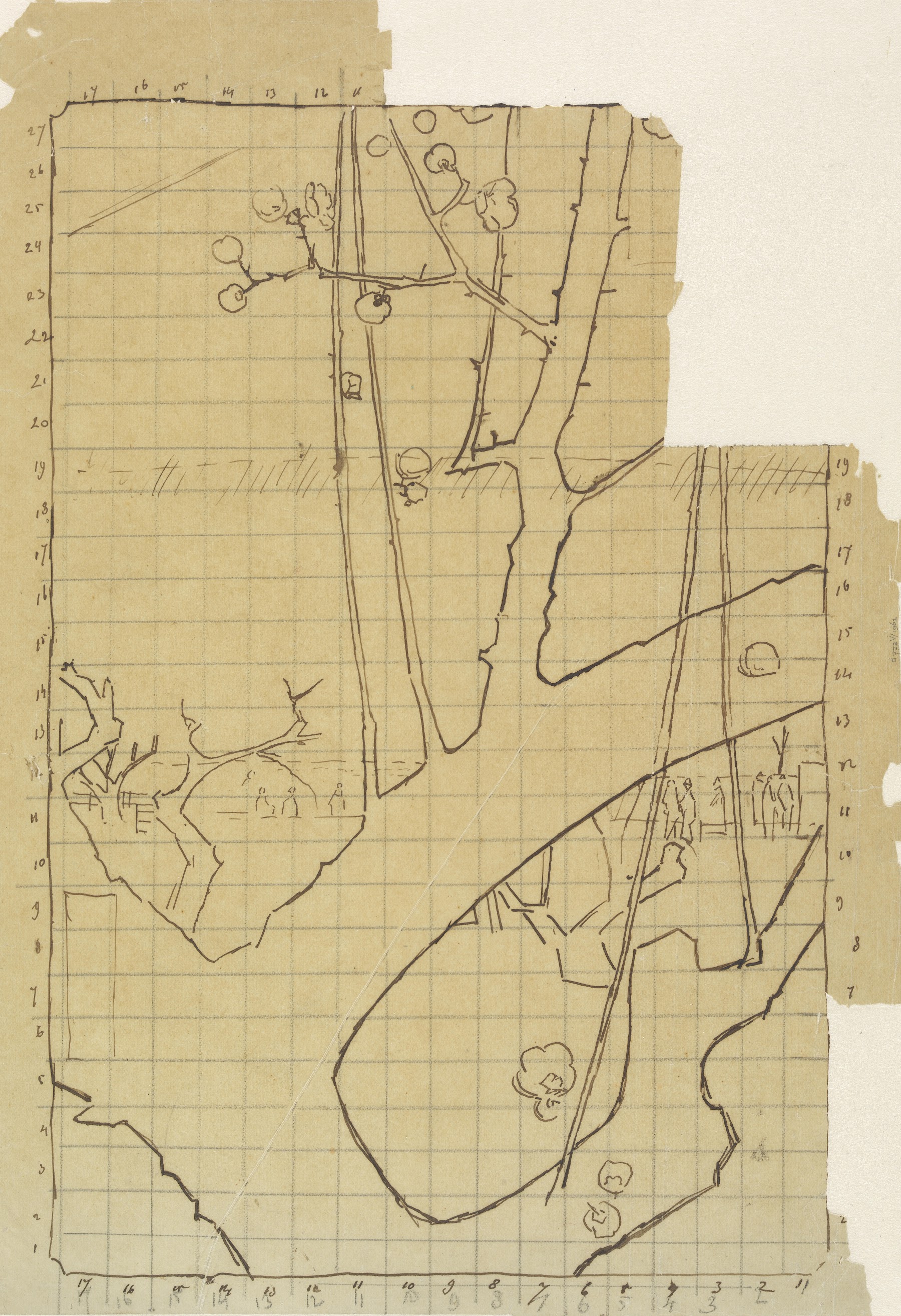

Tracing of ‘The Plum Tree Teahouse at Kameido’ of Hiroshige

Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890), Paris, July-December 1887

pencil, pen and ink, on paper, 38.3 cm x 26.2 cm

Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige)

Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890), Paris, October-November 1887

oil on canvas, 55.6 cm x 46.8 cm

The Van Gogh Museum has made available for download the painter’s collection of Japanese art. As Colin Marshall writes, “Having got a deal on about 660 Japanese woodcuts in the winter of 1886-87, apparently with an intent to trade them, he ultimately held on to them, copied them, and even used their elements as backgrounds for his own portraits.” Through them Van Gogh envisioned his “art of the future”, an expression that “had to be colourful and joyous, just like Japanese printmaking”.

More evidence of the profound effect Japanese art had on Van Gogh appears in a letter to his brother, Theo van Gogh, on Sunday 23 September 1888:

I’ve arranged all the Japanese prints in the studio, and the Daumierss and the Delacroixs and the Géricault. If you come across the Delacroix Pietà or the Géricault I urge you to buy as many of them as you can.

If we study Japanese art, then we see a man, undoubtedly wise and a philosopher and intelligent, who spends his time — on what? — studying the distance from the earth to the moon? — no; studying Bismarck’s politics? — no, he studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him to draw all the plants — then the seasons, the broad features of landscapes, finally animals, and then the human figure. He spends his life like that, and life is too short to do everything. Just think of that; isn’t it almost a new religion that these Japanese teach us, who are so simple and live in nature as if they themselves were flowers?

And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention… I envy the Japanese the extreme clarity that everything in their work has. It’s never dull, and never appears to be done too hastily. Their work is as simple as breathing, and they do a figure with a few confident strokes with the same ease as if it was as simple as buttoning your waistcoat. Ah, I must manage to do a figure with a few strokes. That will keep me busy all winter. Once I have that, I’ll be able to do people strolling along the boulevards, the streets, a host of new subjects. While I’ve been writing you this letter, I’ve drawn a good dozen of them. I’m on the track of finding it. But it’s very complicated, because what I’m after is that in a few strokes the figure of a man, a woman, a kid, a horse, a dog, will have a head, a body, legs, arms that will fit together.

![Kameyama: Wind, Rain and Thunder, no. 47 from the series Collection of Illustrations of Famous Places near the Fifty-Three Stations [Along the Tōkaidō] Utagawa Hiroshige, seventh month 1855](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/vangoghmuseum-n0073V1962-3840.jpg)

Kameyama: Wind, Rain and Thunder, no. 47 from the series Collection of Illustrations of Famous Places near the Fifty-Three Stations [Along the Tōkaidō]

Utagawa Hiroshige, seventh month 1855

Woman Cleaning a Fish, central sheet of the triptych The Fourth Month: The First Cuckoo, from the series The Twelve Months

Utagawa Kunisada, sixth month 1854

Peonies and Blue-and-White Flycatcher, from the album New Selection of Birds and Flowers

Tokyo, 1871-1873 Utagawa Hiroshige III (1842 – 1894)

By studying works by artists including Kunichika, Van Gogh learned how to fill up the canvas with his figures. Just like the Japanese master, Van Gogh used heavy outlines and positioned his subjects against a richly-decorated, flat background, as you can see in Portrait of Père Tanguy.

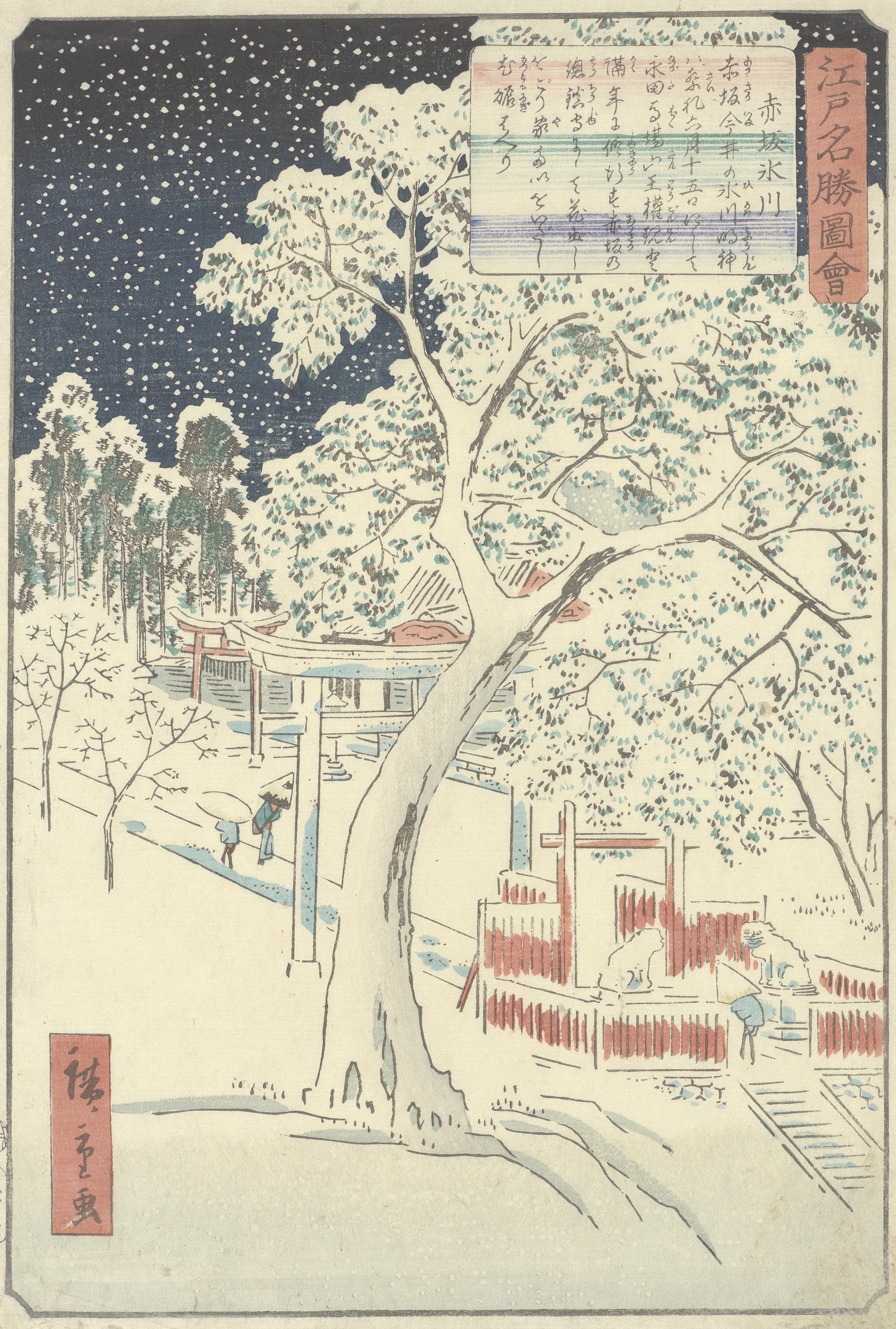

Hikawa Shrine in Akasaka, from the series Collection of Illustrations of Famous Views in Edo

Edo, ninth month 1862 Utagawa Hiroshige II (1826 – 1869)

Actor Tying a Poem Slip to a Cherry Tree, fifth sheet of the pentaptych Favourites All Together in Full Flower

Edo, twelfth month 1858 Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865)

Finches and Pomegranates, from the series Illustrations of Plants, Trees, Flowers and Birds

Tokyo, c. 1875 Togaku

Genji Reflecting on the Flowers at Night, central sheet of a triptych

Edo, first month 1861 Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865)

![Ishiyakushi: The Yoshitsune Cherry Tree near the Noriyori Shrine, no. 45 from the series Collection of Illustrations of Famous Places near the Fifty-Three Stations [Along the Tōkaidō] Edo, seventh month 1855 Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 - 1858)](https://flashbak.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/VanGoghJapanprints-11.jpg)

Ishiyakushi: The Yoshitsune Cherry Tree near the Noriyori Shrine, no. 45 from the series Collection of Illustrations of Famous Places near the Fifty-Three Stations [Along the Tōkaidō]

Edo, seventh month 1855 Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 – 1858)

Shinobazu Pond, from the series Comparison of Famous Places in Tokyo

Tokyo, 1865-1875 Toyohara Chikanobu (1838 – 1912)

Woman on a Riverbank, left sheet of the tryptich The Crystal River of Ide in Yamashiro Province, from an untitled series of the Six Crystal Rivers

Edo, 1847-1848 Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797 – 1861)

Thee actors, central sheet of the triptych Parody of the Drinking Party at Ōeyama with Flowers of Chivalry

Edo, fourth month 1864 Toyohara Kunichika (1835 – 1900)

The Voice of the Dove with the Politeness of the Three Branches, from an untitled series related to animal calls

Edo, ninth month 1853 Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865)

Splendour of Butterflies and Peonies in the Garden, right sheet of a triptych

Edo, 1849 Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865)

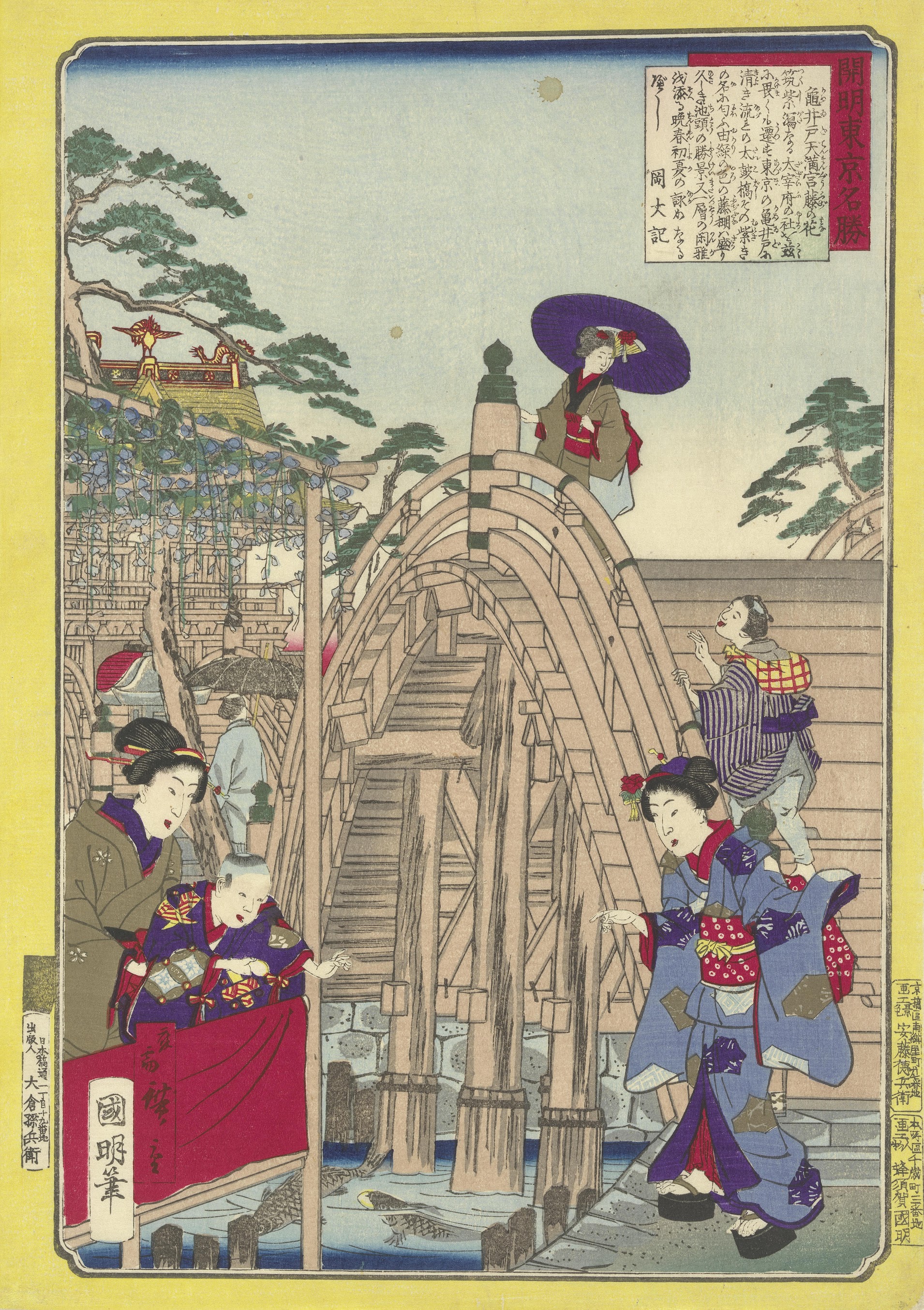

The Wisteria Flowers at the Tenmangū Shrine in Kameido, from the series Beautiful Views on Enlightened Tokyo

Tokyo, c. 1881 Utagawa Hiroshige III (1842 – 1894)

Central sheet of the triptych Celebration of Flowers, Birds, Wind and Moon

Edo, eighth month 1860 Utagawa Kunimaro

Finches and Pomegranates, from the series Illustrations of Plants, Trees, Flowers and Birds

Tokyo, c. 1875 Togaku

The Van Gogh Museum : Van Gogh’s Japanese art collection,

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.