“For me, taking photographs that the GDR authorities did not like was a kind of inner liberation. To not be able to travel freely when you’re young is very depressing. Taking photographs was the work I did to fight against that feeling. A kind of tit for tat. If you hurt me, I hurt you.”

– Harald Hauswald whose photographs recorded everyday life in East Germany

Harald Hauswald, Subway Line A, Berlin, 1986 Metro

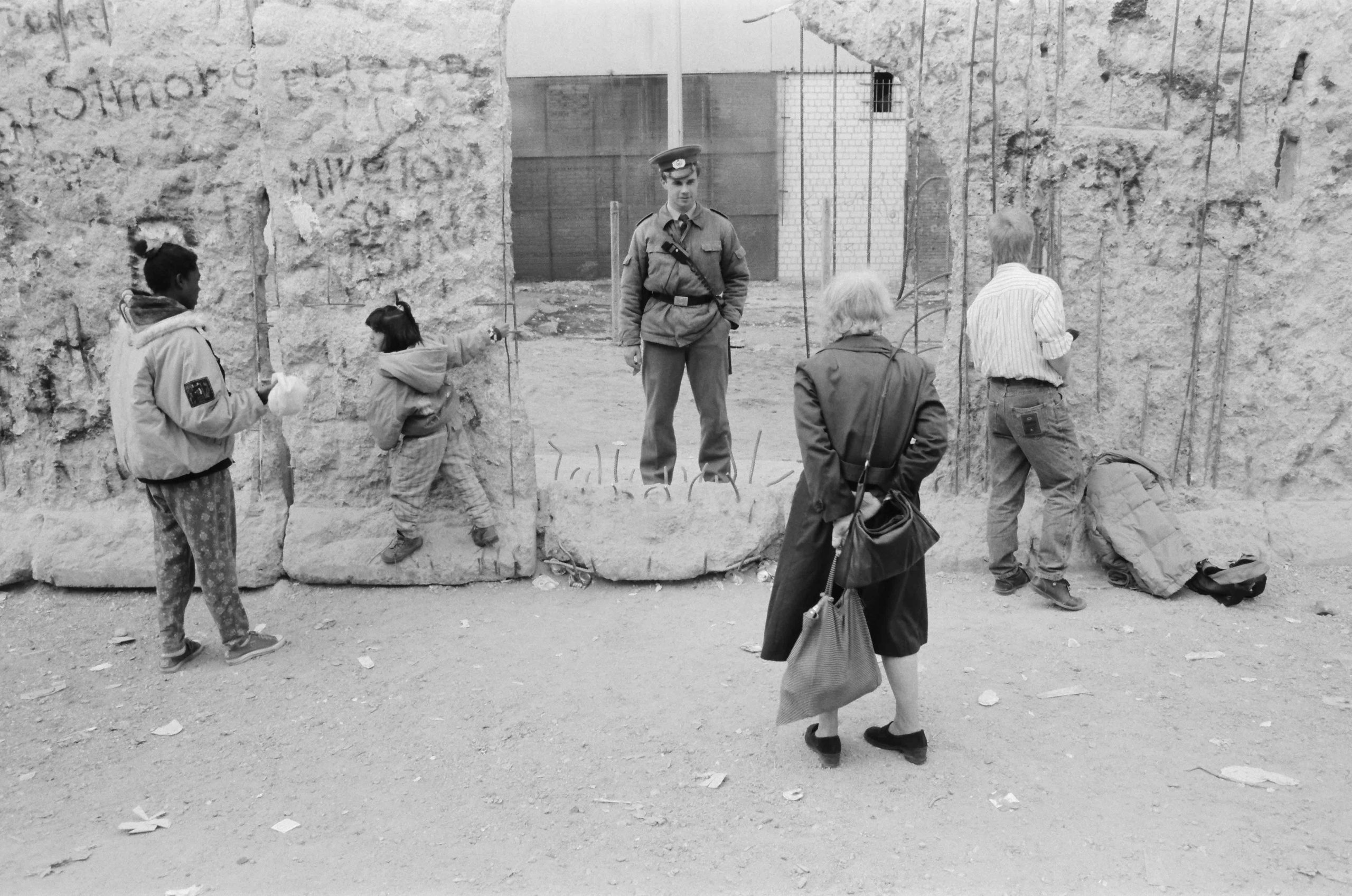

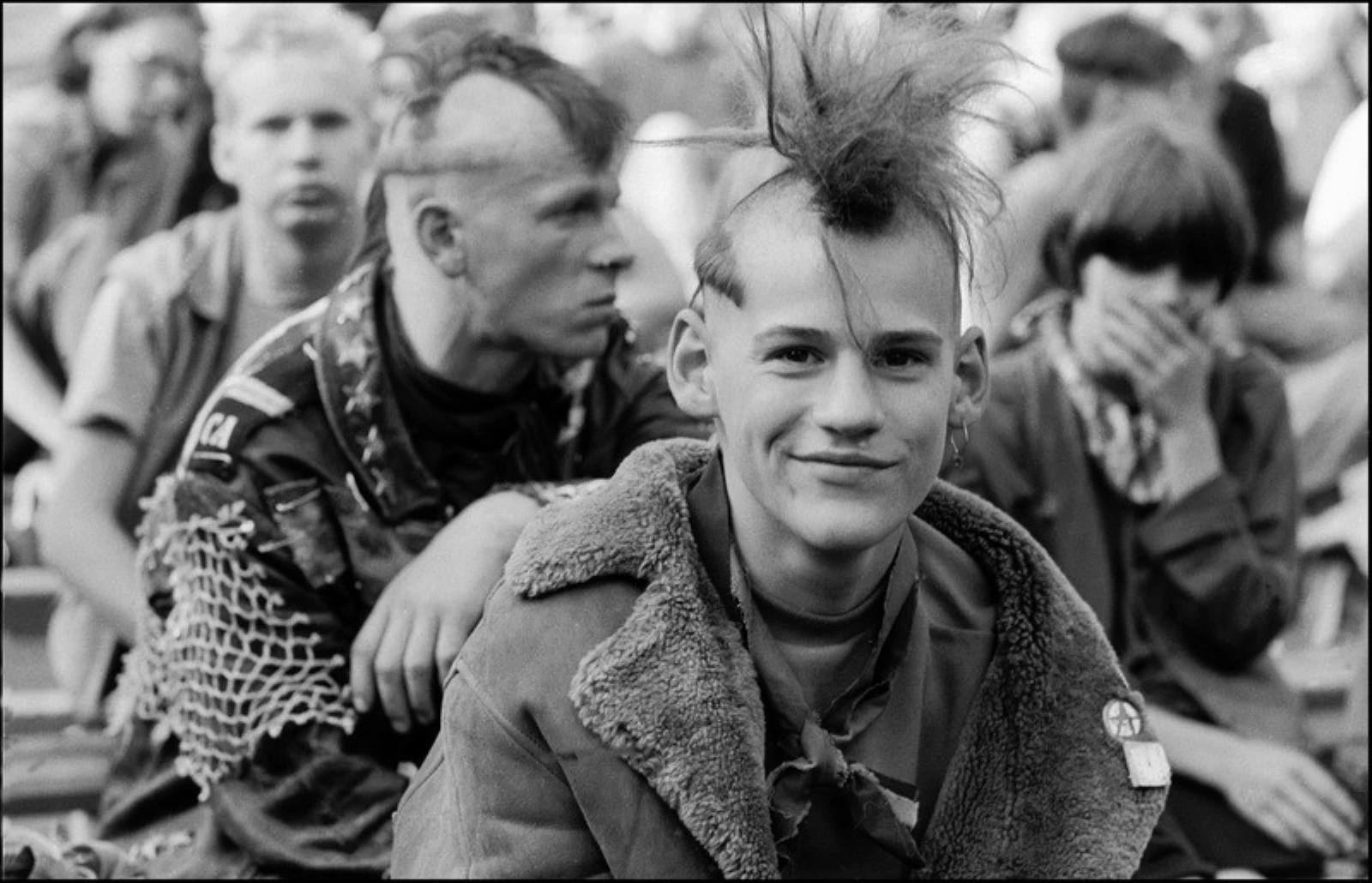

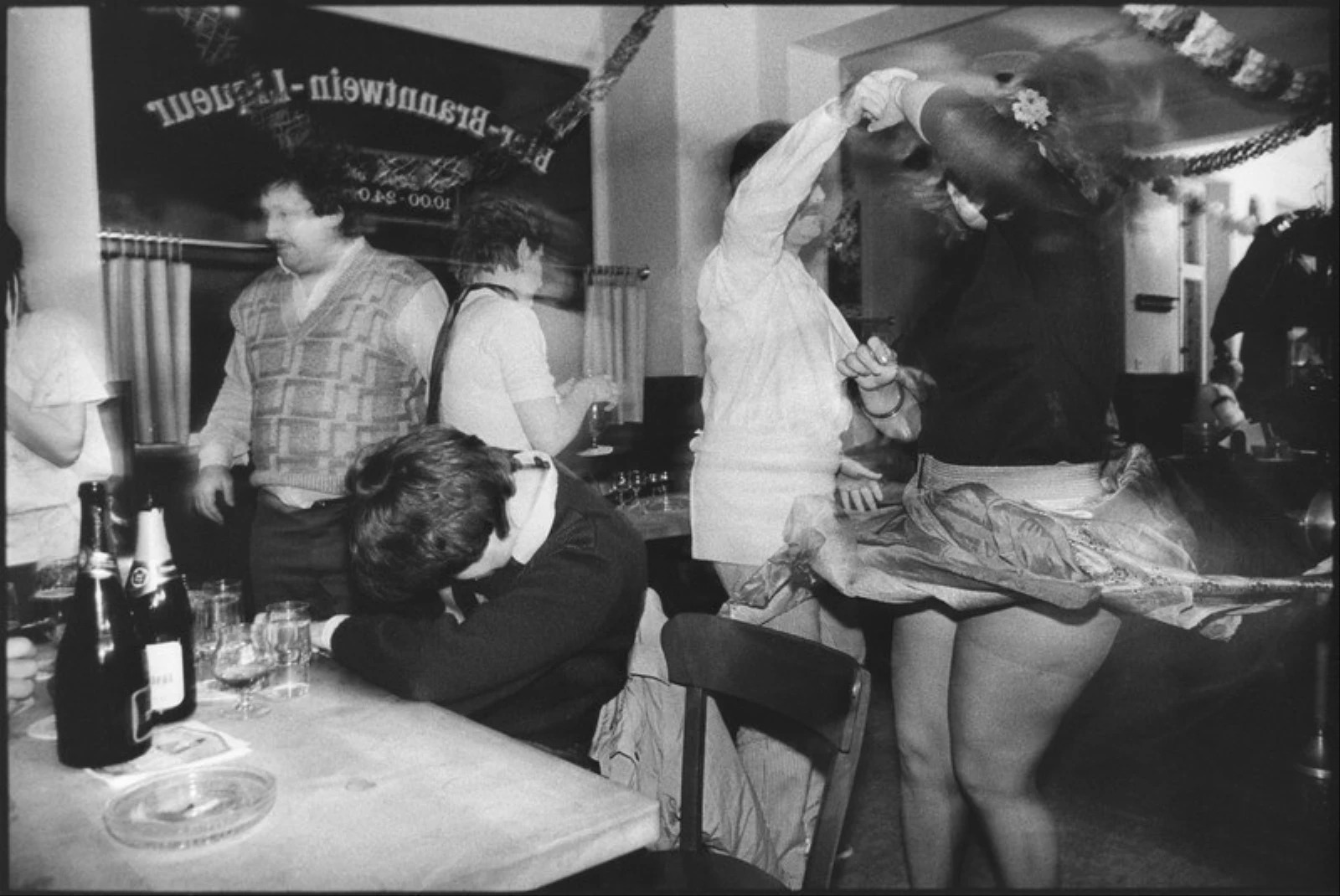

There was a negative freedom in communist East Berlin – a freedom from some of the things that occupy minds. Freedom from things like indecision, movement, choices and self-expression. Photographer Harald Hauswald shows us what it was like to live in the German Democratic Republic, a world full of man-made limits, where one size fitted all – or else.

And as he observed his fellow East Berliners, the State was observing him, tapping phones and bugging rooms, taking notes, building dossiers. Everyone might hate the Germans, as the post-war British say half in jest, but Germans loathed themselves more.

Placed under surveillance by around – get this – more than 40 Ministry for State Security (Stasi) informers, things came to a head in 1985, when the Stasi issued an internal warrant for Hauswald’s arrest on the grounds of anti-state activities, violating exchange-control regulations, currency violations and passing on unclassified information.

The spooks had noticed Hauswald’s work appearing in West German periodicals like Stern, Taz and Zeit magazines. His pictures for one Berlin issue of GEO in 1986 resulted in a ban from the only East Berlin photo lab capable of processing Kodak film.

How did he get his photographs to the West?

“Berlin was a special case, ” he told Vice magazine. “About 15 western journalists were accredited here, who either had a working apartment or actually lived here. I also knew some of them, mostly two; Peter Pragal from Stern. He had his office on Leipziger Strasse in the east and lived in the west. And Hans-Jürgen Röder, from the evangelical press service, lived right here in East Berlin. The two had a border recommendation, a kind of pre-diplomatic status, and were able to bring working materials over uncontrolled. We knew, of course, that their offices were bugged. I always finished my letter, handwritten only, so no sender, and only when I left the apartment did I get it out and when they nodded, they said they were going to West Berlin today and could take the pictures with them.”

Had Hauswald’s gone to prison, he had a plan:

“Naturally I was afraid of going to prison, and by 1985 the state had made it clear they wanted to put me in there for political reasons,” he told Slow Travel Berlin. “But if they had put me in the U-Haft (Untersuchungshaft, or pre-trial prison, which the Stasi routinely used to torture prisoners), my plan would have been to make a request to go to the West, and I would have probably been released within three weeks.” It had worked for his friend, the writer Lutz Rathenow.

Liebespaar auf dem heutigen Schloßplatz, vor dem Außenministerium der DDR, Berlin-Mitte, 1984, Berlin, DDR, Deutschland, Europa

Easy, then, to escape the hive-mind police state, which watched the lives of others for signs of individualism, beat confessions from captives, tortured them and collected their scent on pieces of cloth, so they could be tracked by dogs if they went missing. Easy to escape – in theory.

Such things were messy, of course. Blood seeps and stains. Mess gains attention, especially in the West. Dictatorships and their glorious leaders are vain, thin-skinned and needy. They abhor unflattering photos and bad press. So, the Stasi also used Zersetzung (Decomposition), a form of psychological warfare whereby the undesirable was made to doubt and be doubted. Documents and bank accounts were produced and altered to say the enemy of their class had been making payments to extra-marital lovers, illegitimate children and sex shops. Home break ins resulted in alarm clocks set to go off at 7m ringing at 1am, and objects – razors, shoes and the mundane – going missing.

“At one point I opened the door and found them standing outside my apartment,” Hauswald’s recalls. “They took me to the police station in Senefefelder Strasse, whose first floor was used by the Stasi. Their plan was to draft me into the National People’s Army, but I told them I had an 11-year-old daughter to take care of. So they took take my daughter away, which was one of hardest times of the whole era for me, and for her too.”

She was soon sent back. But as a single parent, the State had put Harald’s daughter in an orphanage for six months when she was eight and he was forced to join the military. “I knew she was unhappy, and I was too,” he recalls.

Menschen laufen, nach Öffnung der Mauer am 22.12.89, auf das Brandenburger Tor zu, 1989, Mitte, Berlin, DDR, Deutschland, Europa

On 9 November 1989, five days after half a million people gathered in East Berlin in a mass protest, the Berlin Wall dividing communist East Germany from West Germany fell. Harald Jäger was the border guard in charge that evening. In 2009, he told Der Spiegel in 2009 that he had watched a spokesman for the State say that private travel outside the country could be applied for without prerequisites. Jäger had received no news. No directive. A guard with no orders is just a man stood by a wall. “People could have been injured or killed even without shots being fired, in scuffles, or if there had been panic among the thousands gathered at the border crossing,” he told Der Spiegel. “That’s why I gave my people the order: Open the barrier!”

“The opening of the Wall was without a doubt the best moment in my life,” Harald told Huck Mag. “Even though I would say my childhood was great, because it was only with puberty that I start considering political questions, and even my adult life was fairly decent life despite the surveillance and everything, the Wall falling meant we suddenly had freedom, which is something I am still grateful for today. I think those who thought they could get more freedom without that happening were living under an illusion. The idea of socialism isn’t a bad one, but humanity isn’t built for it, it goes against its nature. It’s always ruined by power and money, and always corrupted. That was always my belief and it still is. And for me, the Wall falling was also lucky timing because I was 35 — a good age to start again.”

Harald Hauswald, Concert of Big Country, Radrennbahn, Weißensee, Berlin, 1988

Born in 1954 in Radebeul, Germany (near Dresden), Harald Hauswald studied photography in the 1970s. In 1977, he moved to Berlin where he worked as a telegram messenger and assistant in a photo processing lab. From 1981 to 1989, he worked as a photographer for the Stephanus Foundation.

He was a founding member of the Ostkreuz photography agency in 1990, alongside Sibylle Bergemann and Ute and Werner Mahler.

Harald Hauswald, Eythra, bei Leipzig, 1986 by Harald Hauswald

Hauswald, Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, 1980er-Jahre by Harald Hauswald:OSTKREUZ:Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung

Deserters, May 1 Demonstration, Alexanderplatz, Mitte, Berlin, 1987

In 1997, Harald Hauswald was awarded the Bundesverdienstkreuz (Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany), and in 2006 he received the Einheitspreis–Bürgerpreis zur Deutschen Einheit (Citizen’s Award of German Unity). He and his work are also featured in the 2007-2009 European Union-sponsored project “Overcoming Dictatorships.” As of 2013, he continues to live and work in Berlin.

In 2022, C/O Berlin, inging together around 250 of his pictures in a comprehensive retrospective entitled “Full Life!” and put them in a dialogue with parts of his Stasi files. The “new exhibition is the largest and most important of my life – an international stepping stone,” he said. “It follows much work to conserve and digitise my catalogue, around 7,500 reels of film, revealing many photos which I’ve never seen before.”

Ostkreuz has a Store where you can purchase limited-edition photographs by the Ostkreuz photographers.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.