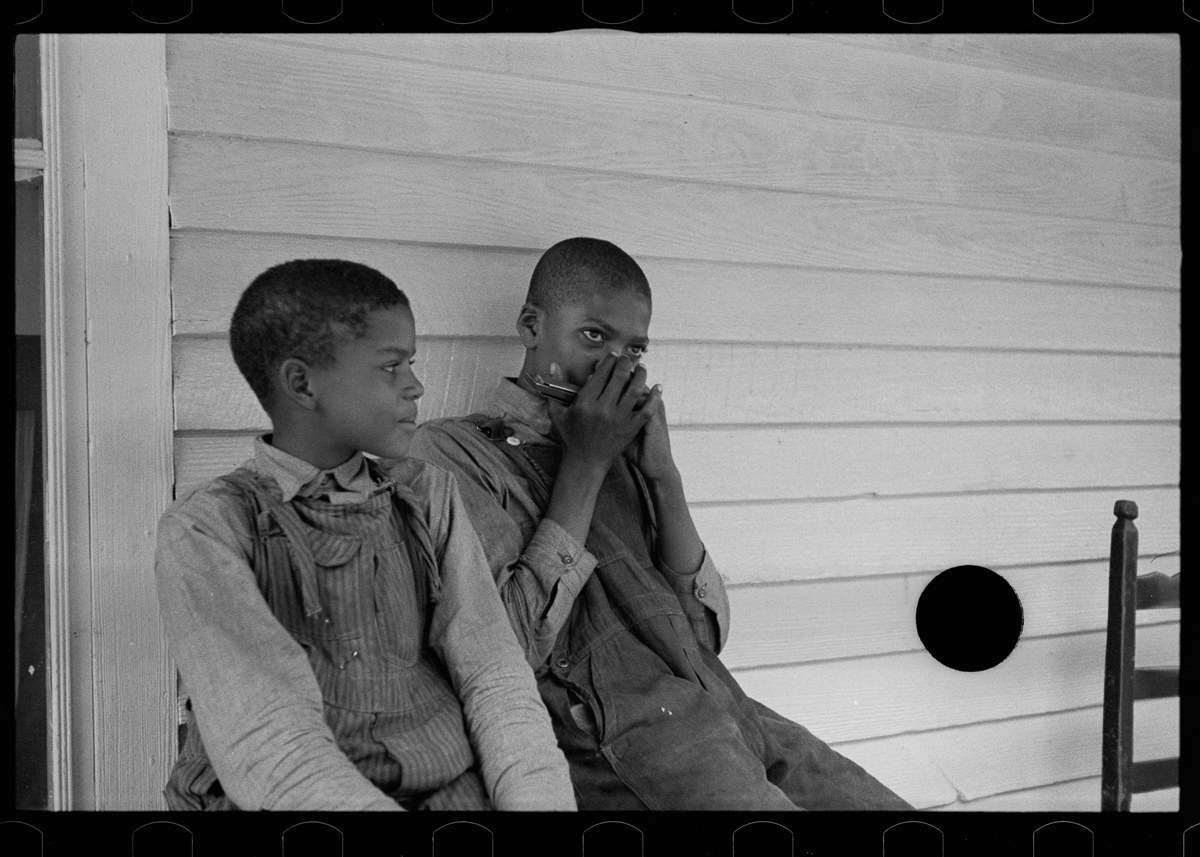

We’ve featured many pictures from the US Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) ambitious project to document the lives of farming families during the 1930s. We’ve witnessed Migrant Mothers, Dorothea Lange’s elegant portraits of life in The Dust Bowl, viewed haunting and powerful pictures of Appalachian families, spent a day in London, Ohio, taken a look at heavy industry at Corpus Christi, Texas and attended a Square Dance in McIntosh County, Oklahoma.

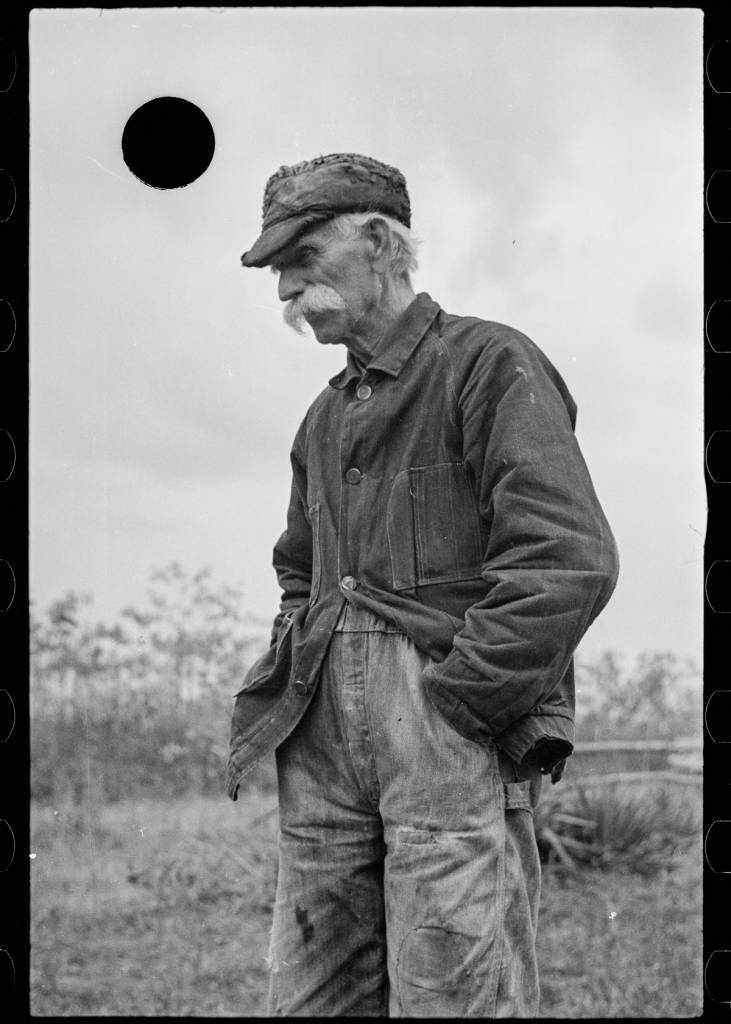

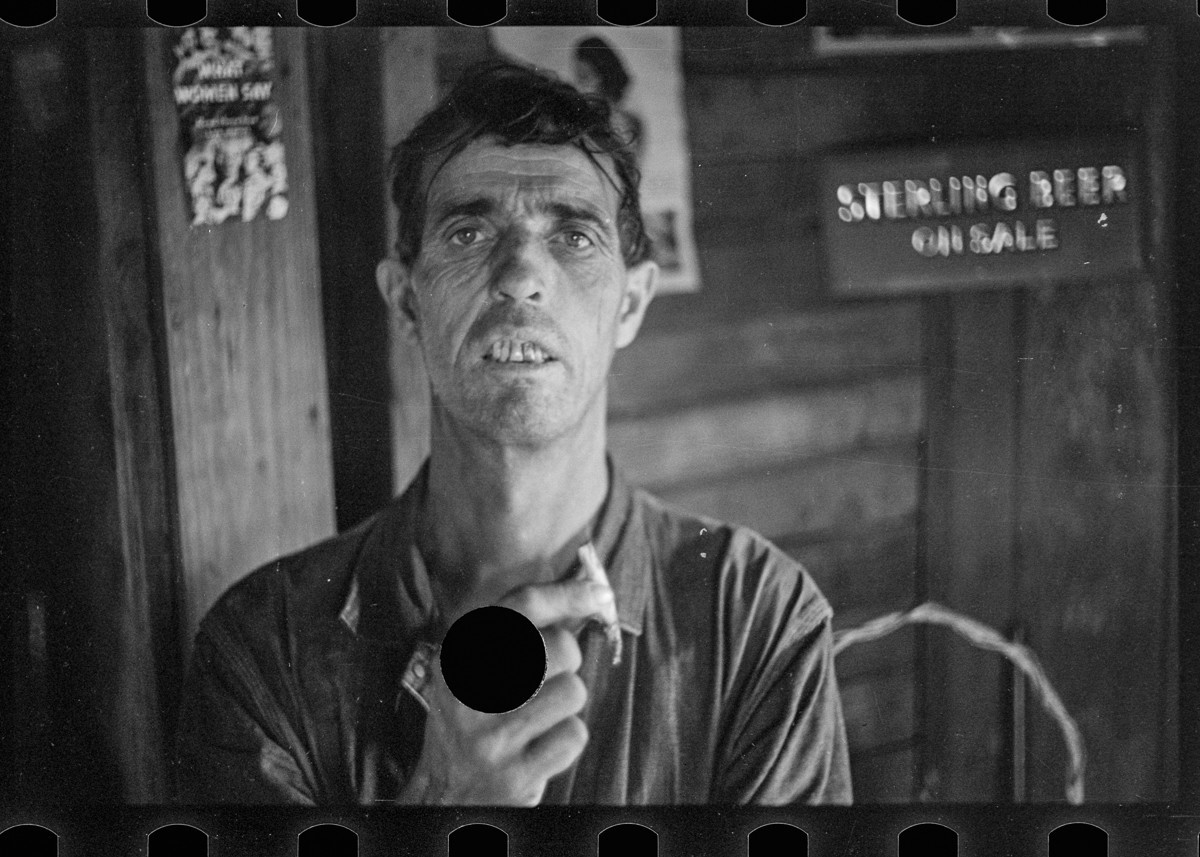

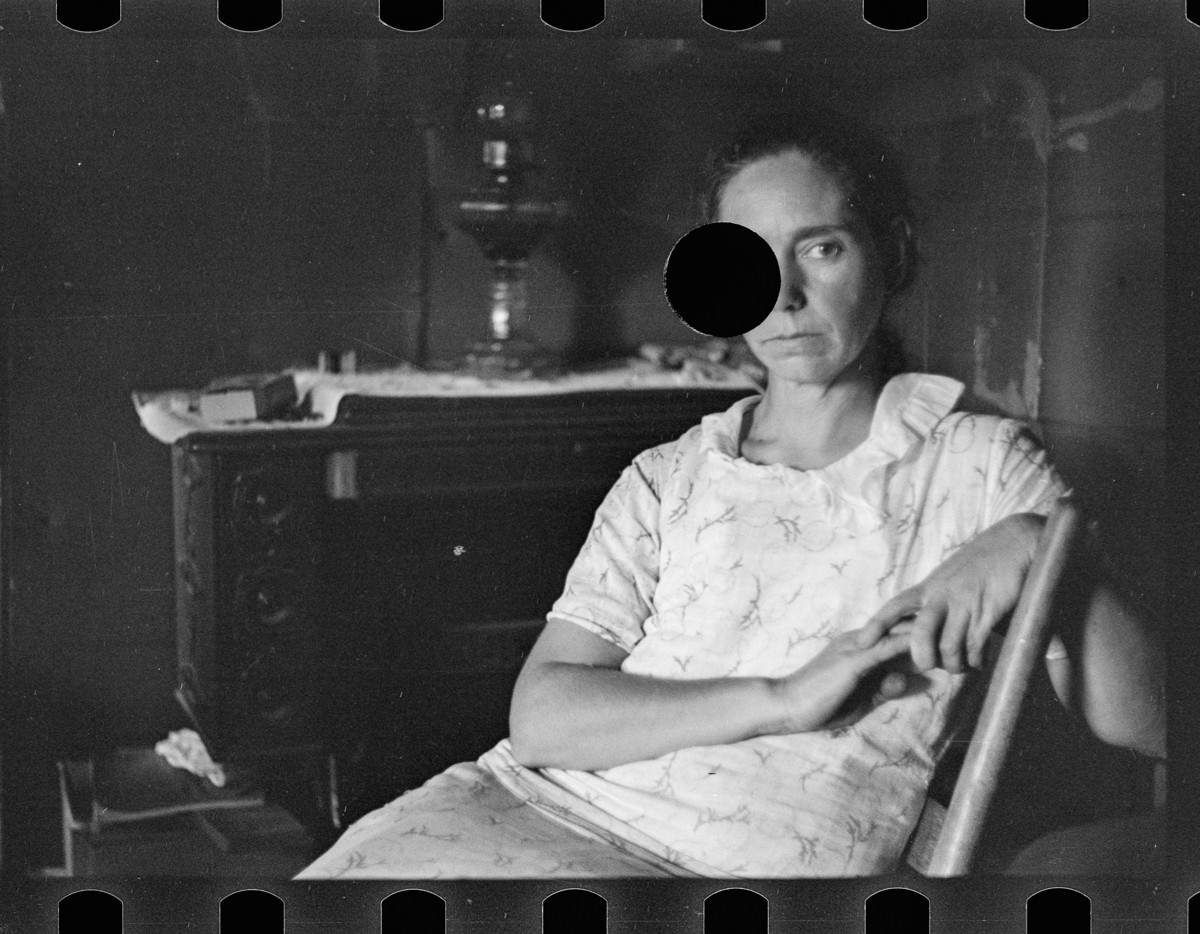

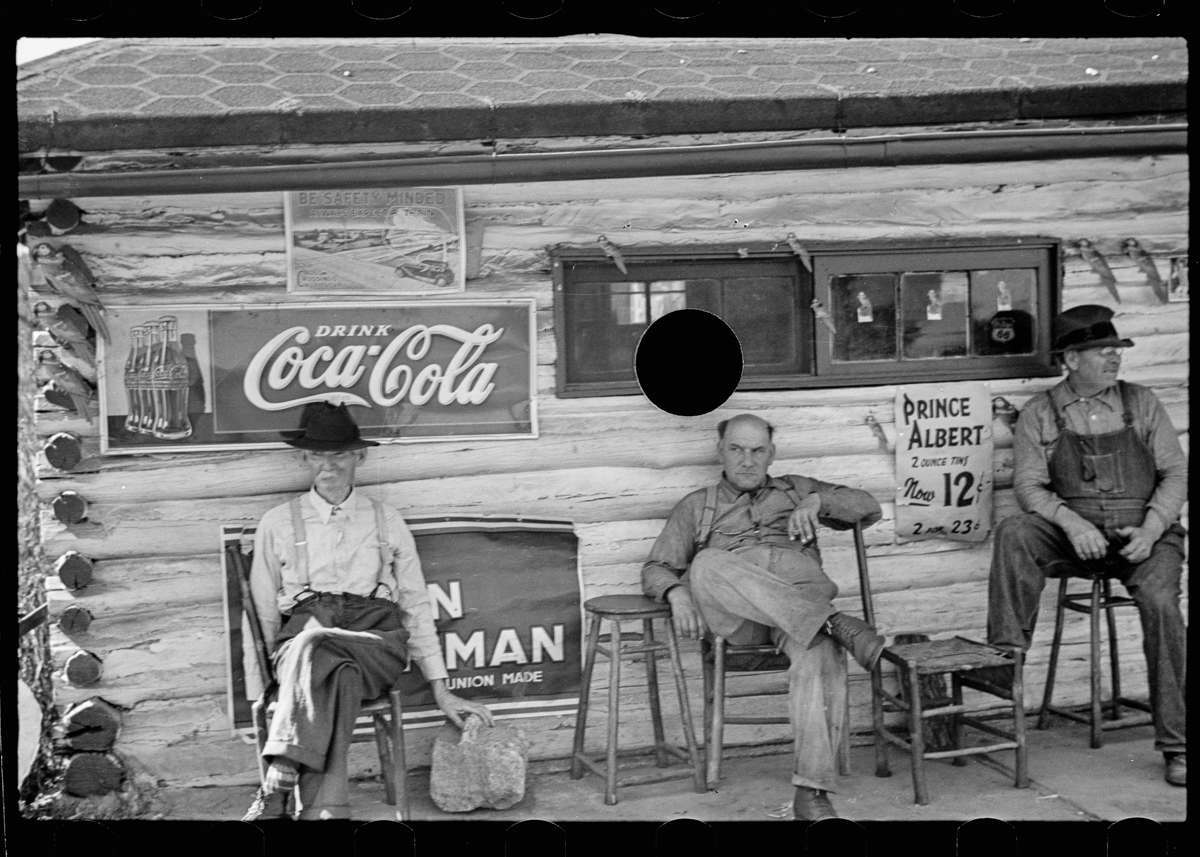

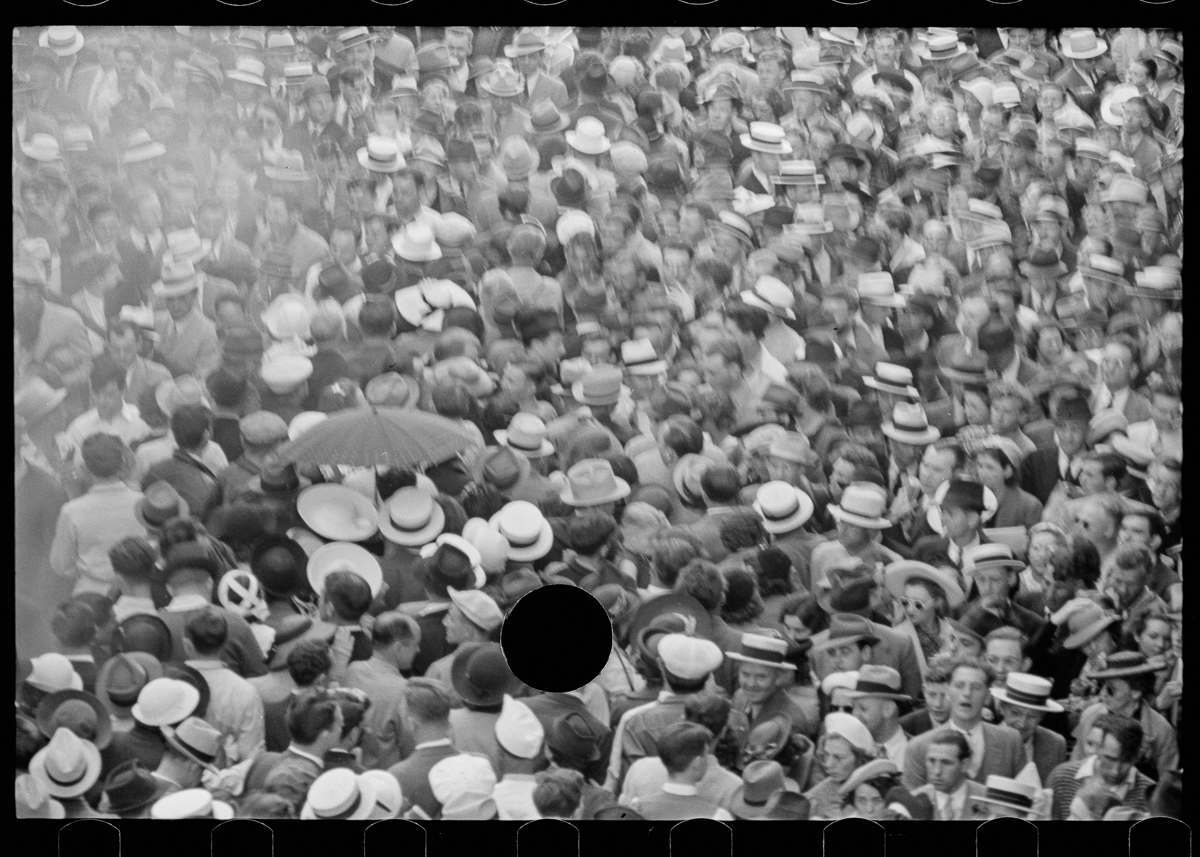

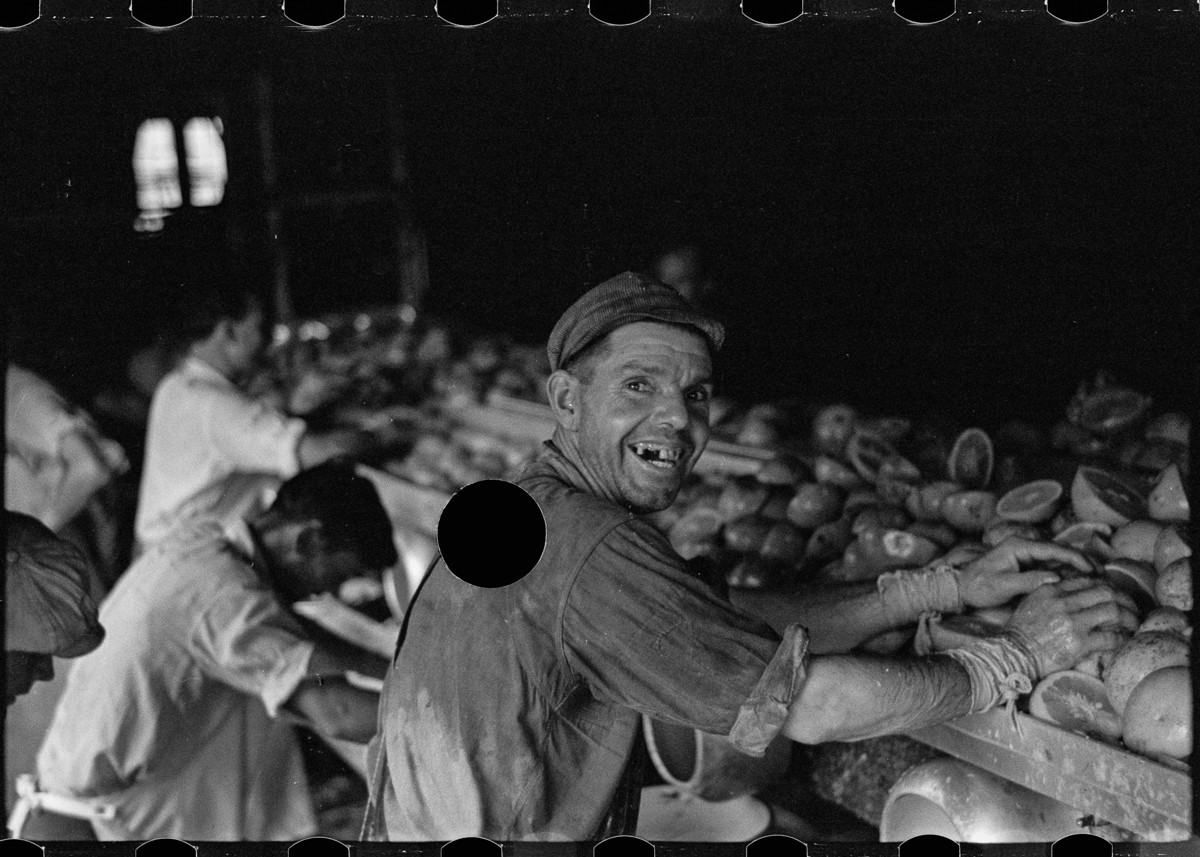

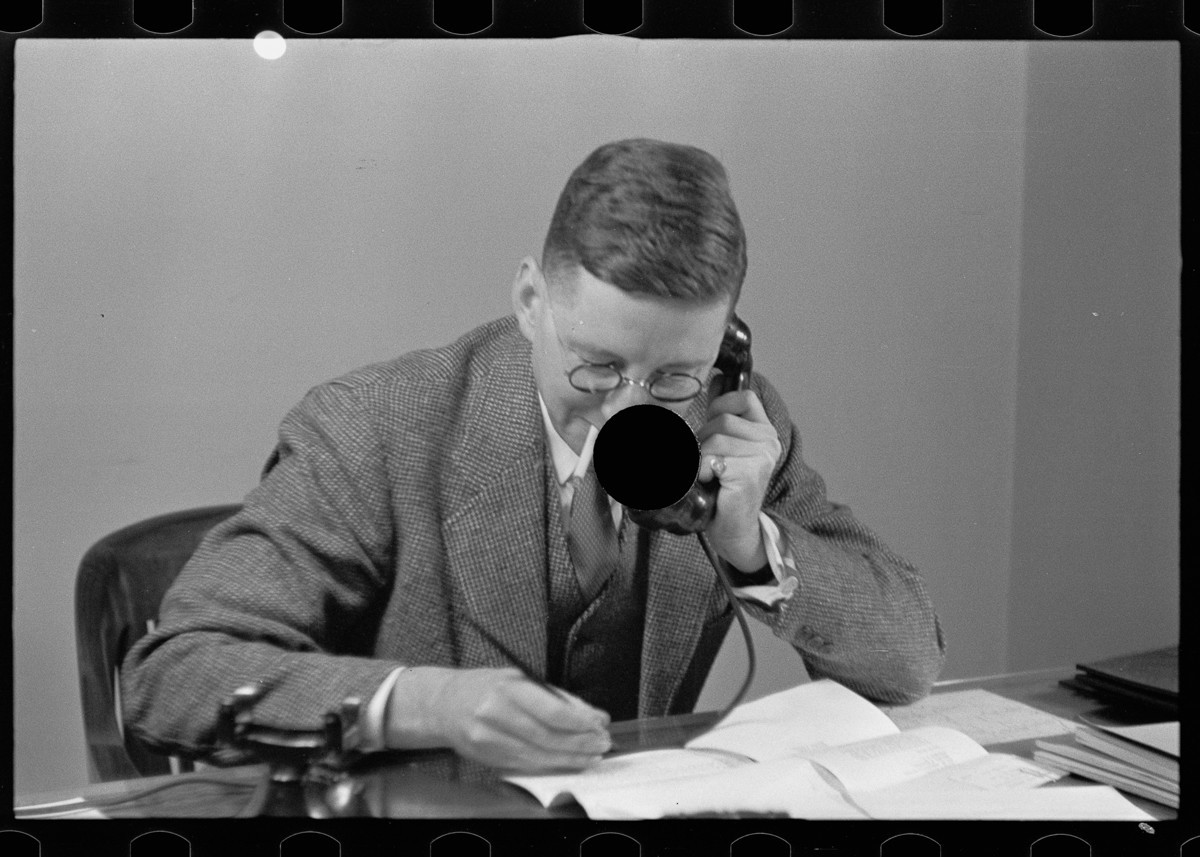

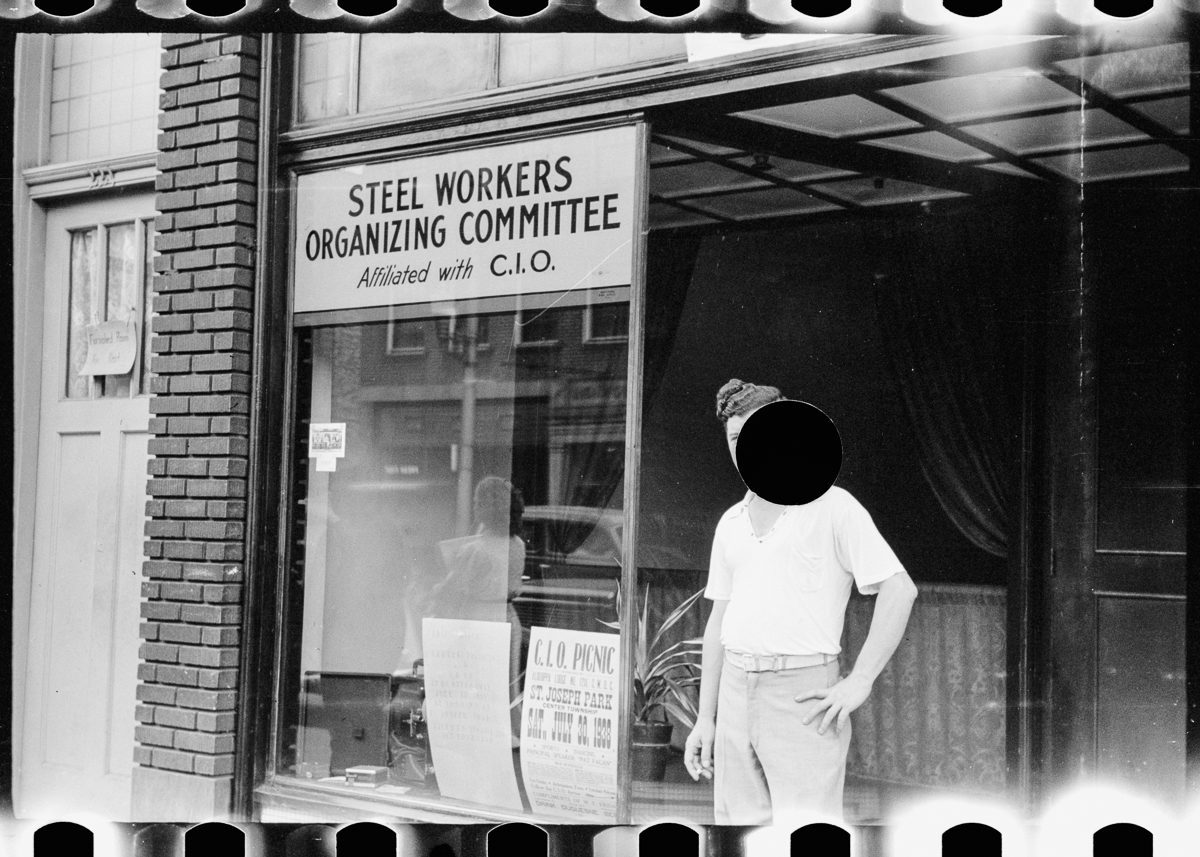

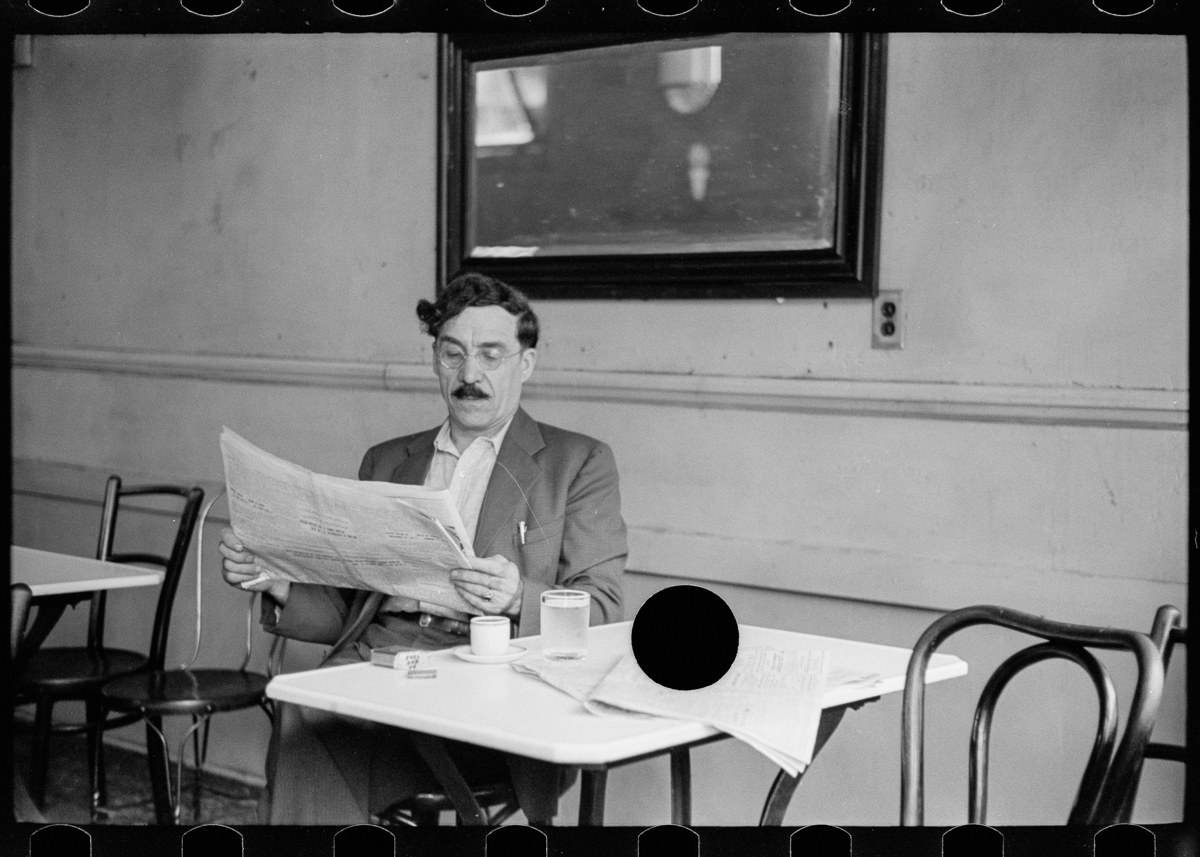

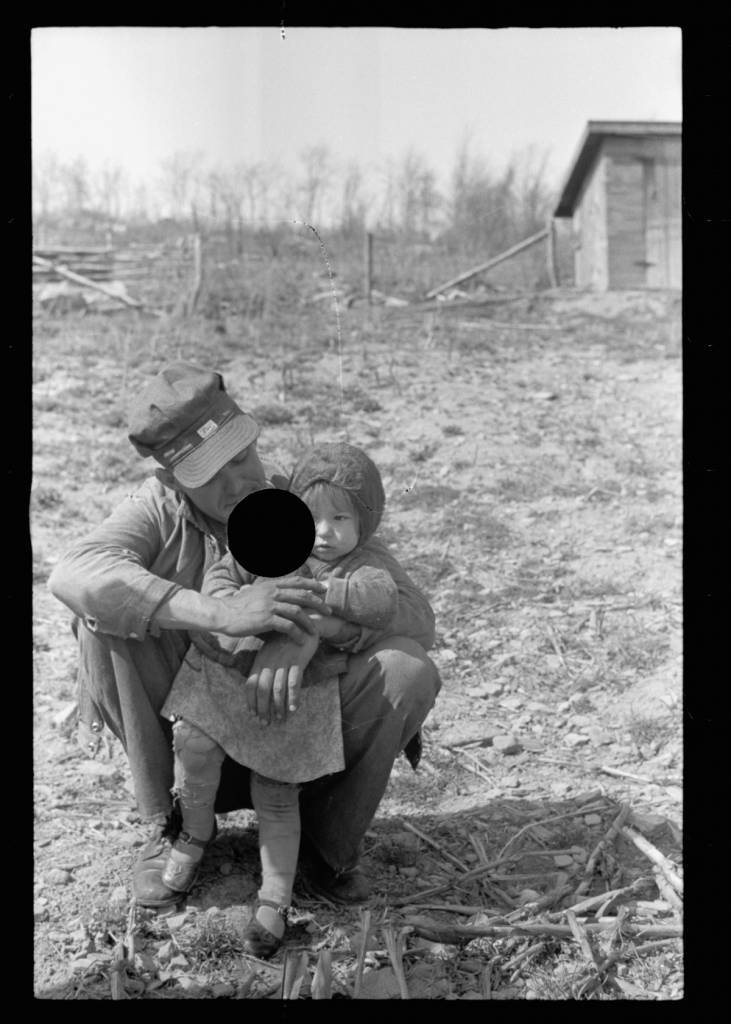

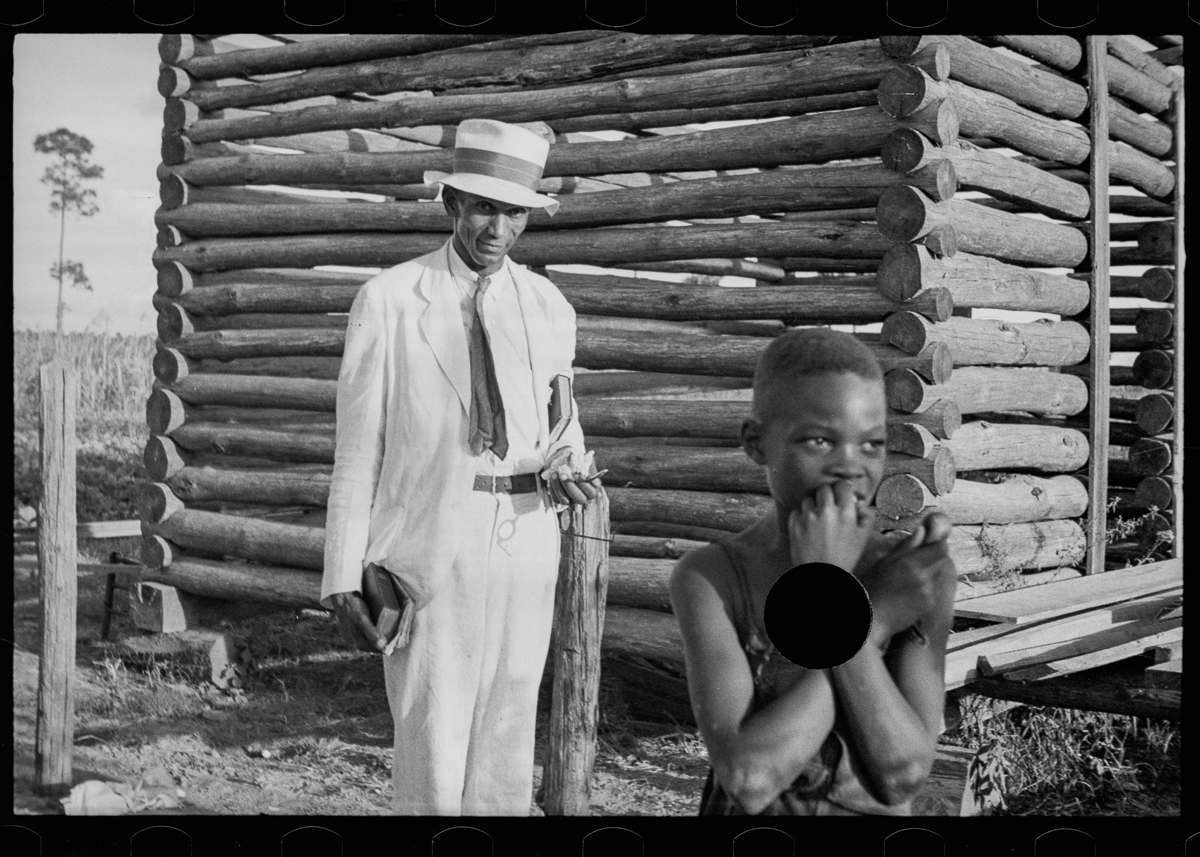

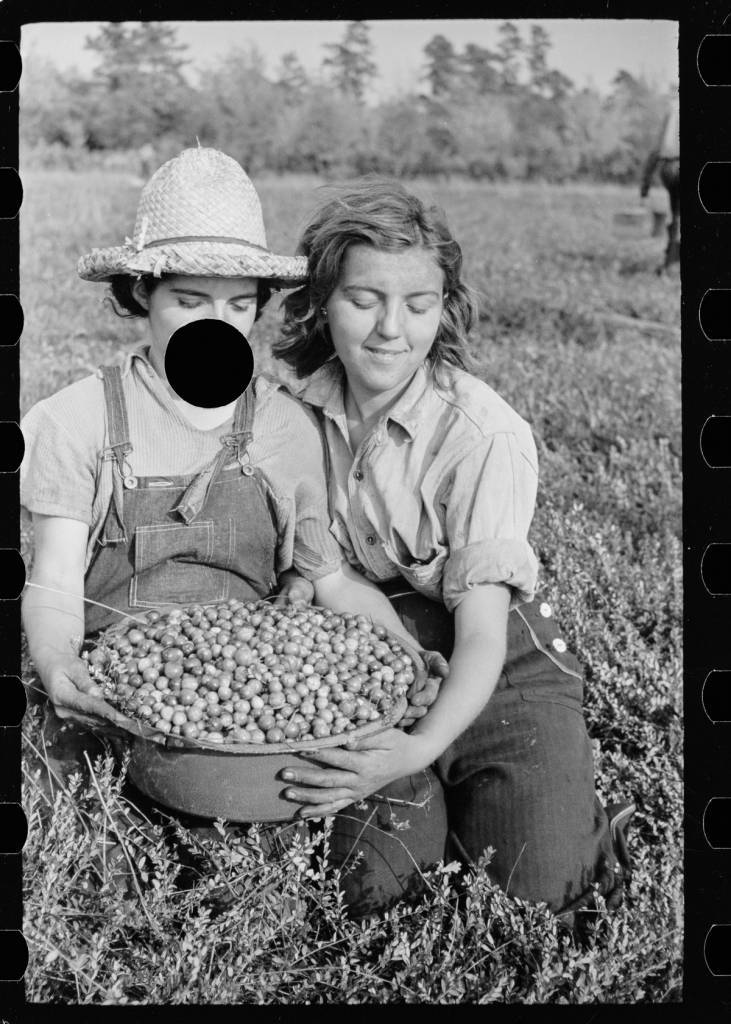

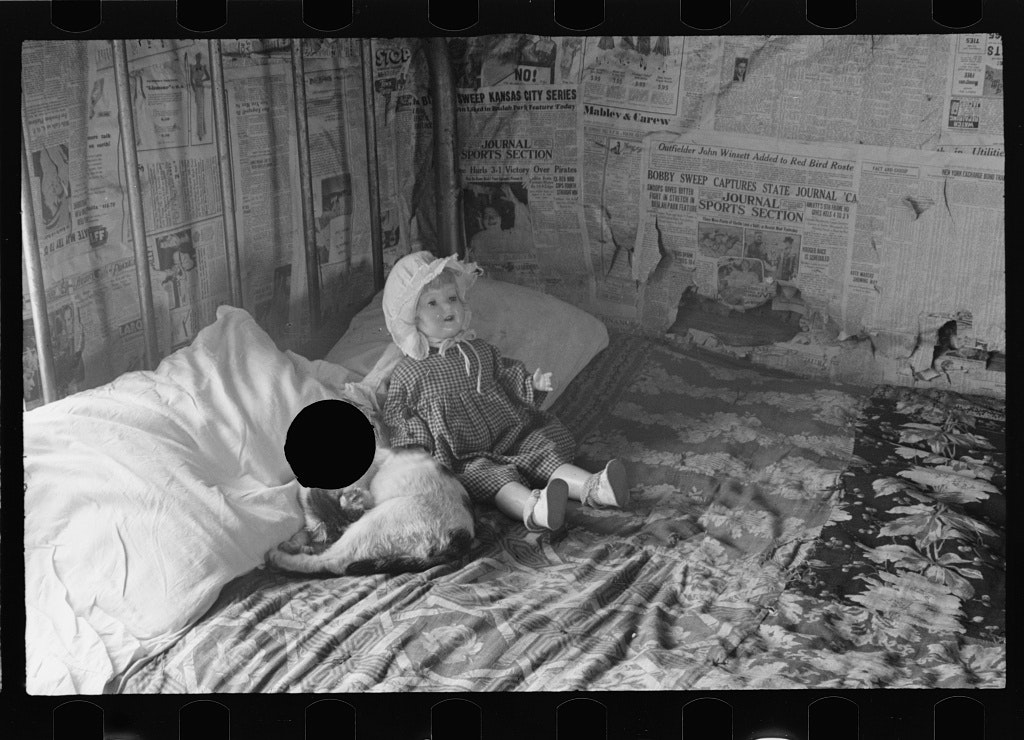

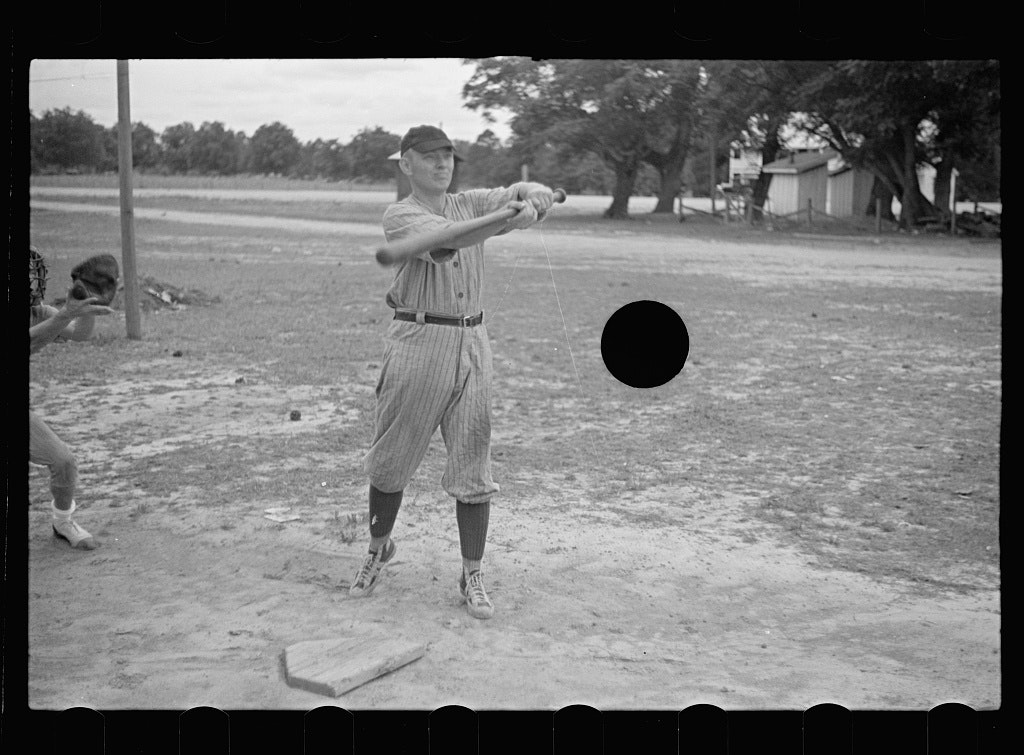

Now we can show you what the censors didn’t want you to see: the black hole photographs. These pictures each contain an inky black disc of nothing. A black sun hangs with pendant menace and mystery.

But they’re neither objects nor stains, rather punch holes made by Roy Stryker, director of the FSA’s documentary photograph program, and his team of editors. The holes marked pictures as unfit for purpose. But what was the purpose of the Government program if not to show it all?

The holes have become additions, extra points of interest.

Why were these images killed? What is it about each image we see here that caused the editors to act as censors? Looking at the holes in the sky, we might put on our tinfoil hats and look for conspiracy, supposing the images have been redacted to remove traces of flying objects. What is the man picking up from the grass? Why is another man’s face obliterated? Who is the missing face in the crowd?

At the final count, around 100,000 images by photographers like Gordon Parks, Russell Lee and Marion Post Wolcott had been ‘killed’.

Photographer Edwin Rosskam thought Stryker’s hole-punching “barbaric”, adding: “I’m sure that some very significant pictures have in that way been killed off, because there is no way of telling, no way, what photograph would come alive when”.

Ben Shahn was outraged:

“He ruined quite a number of my pictures… Some of them were incredibly valuable. He didn’t understand at the time. . . . Later on, during the war … I went to look for [a] negative and he[‘d] punched a hole through it. Well, I shot my mouth off about that. But, I didn’t know what was done with a lot of my negatives, naturally. He learned, then, not to do that, you see, because this was an invaluable document of what life was like in 1935 and when I was looking for it in 1943 or ’44 it didn’t exist anymore.10

A chastened Stryker eventually granted veto power to photographers over which of their images would be killed.”

Today we can see them all at the National Archives. But back then the desire to show the places and faces of America in the mire was controlled to fit a message.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.