THE second-highest grossing film of 1977 (right behind George Lucas’s Star Wars) was Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of The Third Kind, a science fiction film concerning mankind’s first official contact with alien life-forms.

Close Encounter’s narrative also involves the mystery behind alien abductions and the truth regarding a government conspiracy to keep the existence of UFOs a secret.

Throughout the film Spielberg cross-cuts between two major plot-lines: a scientist’s (Francois Truffaut’s) efforts to develop a language so as to communicate with the visiting aliens, and one blue-collar worker’s (Richard Dreyfuss) personal journey to better understand their uncomfortable — but growing — presence in his daily life…and inside his very head.

Importantly, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) was described by Science Digest as a film that is “tantamount to faith.”

The same publication noted too that Close Encounters’ sense of faith, so “wondrous and thoroughly spiritual – is registered in nearly every frame, reaching a climax in its messianic ending.”(Joy Boyom, Feb 1978, p.17).

Similarly, Gregory Richards’ monograph, Science Fiction Movies (Gallery Books, 1984, p.61) contextualizes Spielberg’s disco-decade UFO epic “as more of a religious film than a science fiction one.”

So the primary question that viewers must reckon with regarding this cult classic is: why have so many reviewers contextualized the Spielberg film as one of an overtly religious nature? Does an understanding of the religious allegory open up new avenues for understanding this work of art?

Or contrarily, does the religious explanation of Close Encounters only serve to cloud the secular, humanist message beating at the movie’s heart?

Close Encounters as Religious Allegory

In part, the categorization of Close Encounters of the Third Kind as a film about spirituality and faith arises because Steven Spielberg’s movie so abundantly features what David A Cook, author of Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970 – 1979, calls “an aura of religious mystery.” (University of California Press, 2000, p.47).

Roy Neary — much like the apostle Paul on the road to Damascus according to Paul Flesher and Robert Torry in Film and Religion: An Introduction — experiences a kind of spiritual dawning or awakening.

In particular, Neary sees a UFO and hears the call of the aliens (transmitted via a telepathically implanted, subconscious “message” or “vision.”)

At first he does not understand the alien message. What is the meaning of the strange thoughts in his head? Why does he feel compelled to undertake a pilgrimage –– a journey to a location of great importance to one’s faith — to some mountain he has witnessed seen only in his mind?

Eventually, however, Neary surrenders to the vision, to his faith. He forsakes all his worldly belongings and connections — including his family — in a devoted (and perhaps mad…) attempt to understand why he has been “chosen” to hear this call from a (literally) Higher Power.

Clearly, Neary seeks communion with the message’s sender…with a stand-in for God. His quest in Close Encounters thus reflects Scripture and Romans in particular. “Faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ.” Here, Neary has heard and honored that word, but it is the words of the aliens.

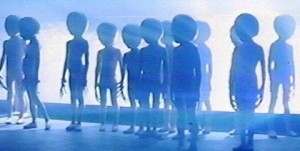

Neary’s hardship and trials are eventually vindicated. At last, he meets the aliens at the mountain of his vision (ironically at a place called Devil’s Tower), and then watches as a version of the second coming of Christ is re-enacted before his eyes.

According to Flesher and Torry (Abindgon Press, 2007, p.200), the returned abductees whom the aliens release from their landed mother ship symbolically represent the dead rising, or the resurrection of the dead as foretold in Scripture. And furthermore, the ascent of the alien craft to outer space with one of the faithful (Neary) ensconced aboard it similarly represents the Christian rapture, the trip to Heaven, essentially.

Even the physical appearance of the aliens in Close Encounters might be readily interpreted as strongly reflecting Christian apotheosis.

In form, the extra-terrestrial bodies “have no clear blemishes or gender, suggesting that superior beings transcend the normal categories of physical existence and approach the ethereal qualities associated with spirits and angels,” notes scholar Eric Michael Mazur, (Encyclopedia of Religion and Faith (ABLC-CLIO, LLC 2011, page 388).

In his final ascent to the stars, to Heaven, Roy Neary is wholly affirmed in his unyielding faith and belief in the vision he received, over his wife’s cynicism and stubborn skepticism, and over the U.S. Government’s attempt to “control” the meeting of man and alien.

In some sense, Close Encounters is all about taking a leap of faith, and that very idea finds resonance in one of Spielberg’s compositions. Confronted with the government lie about a deadly and toxic nerve gas spill in Wyoming (near Devil’s Tower), Neary chooses to “believe” his own narrative instead. He rips off his protective gas mask and breaths the purportedly contaminated air. But he is proven right…he survives, and his faith is replenished.

Given the alien angels, the metaphor for the Second Coming and even this leap of faith, the overall effect, therefore, of this cinematic journey is indeed, well, rapturous.

Strangely, however, there is a dark aspect to this story of religious awakening that one must also weigh.

While it is true that Roy Neary transitions from an unhappy and spiritually bereft life to one of faith and purpose, the cost of such knowledge of God (or God surrogate, in this case) is his very family. In the act of proving his faith and his worthiness of being “born again” in the stars, Roy abandons his family on Earth. This abandonment is literal, not metaphorical.

The non-believers — including his children — get “left behind” to toil in the world without his guidance or even presence. And again, the message could be interpreted as strongly religious.

If you don’t “believe,” you don’t get saved.

Lastly, even Close Encounters’ famous tag-line “We Are Not Alone,” could be easily parsed in a religious, “God is my co-pilot” sense.

Close Encounters as a Secular Film about Self-Fulfillment

An alternate reading of Close Encounters suggests this cinematic work of art from Spielberg is actually a humanist film, the secular tale of a man who chooses to no longer be enslaved to society’s destructive constructs (including government, career, and family), and to follow his own individual path instead.

The story, again, is of Neary breaking free of constraints, but the breaking free in this reading is from a society that lies, cover-ups, and demands his perpetual unhappiness for its continuance.

The fact that Spielberg plays the song “When You Wish Upon a Star” at the conclusion of Close Encounters of the Third Kind is the primary support for this reading.

One lyric in that composition suggests a direct rebuke of faith, or religious identification. When you wish upon a star it “makes no difference who you are,” the song goes. In other words, you need not be affiliated with any particular group or belief system if you hope to achieve your dreams. You need not believe in God or a higher power. Instead, if you must merely “wish” and voice your “dreams,” you will be rewarded for following the best angels of your — human — nature.

In terms of history, Close Encounters of the Third Kind followed closely on many frissons in American politics, and this context, likewise, suggests a more humanist reading.

President Richard Nixon had been toppled in the Watergate Scandal in 1974, for example. His resignation and culpability in illegal activity suggested that “faith” or “belief” in the pillar of leadership was not such a good idea.

Similarly, the Vietnam War had ended in ignominy for the U.S. in 1975. The cause that so many Americans fought for (and died for…) was lost, and this very idea seems reflected in Close Encounters’ final scene.

There, a line of carefully vetted and approved government officials (surrogates for soldiers in Vietnam?) are overlooked by the aliens in favor of the “Everyman,” Roy Neary.

By contrast to these seemingly emotionless, expressionless, thoughtless drones, he is a man who chose explicitly not to believe the fairy tales his government was peddling. He has thus established his independence and his resourcefulness outside of Earthly and national considerations.

In this reading, the “leap of faith” of taking off the gas mask is actually the dawning awareness that — because of Watergate and Vietnam — the U.S. Government could no longer be trusted, or be considered an agent for honesty.

But again, in this reading of Close Encounters, one must reckon with Neary’s pure selfishness, his very questionable decision to leave his children and wife behind for his own individual “self-fulfillment.” And again, one must note that very idea of “sweet fulfillment” is explicitly voiced in the lyrics to the song “When You Wish Upon a Star.”

Yet I would suggest that Neary’s act of leaving his family (and his government, and his job…) behind in 1977 would not have been looked at by many audience members as purely a bad thing.

One must recall that the 1970s was determinedly the decade of the “self,” a fact reflected in the hedonism of disco music, and the blazing ascent in popularity of the “self-help” book genre. Popular buzz-words of the day included “self-realization” and — sound familiar? — “self-fulfillment.”

Yet as the movement of “self” grew in the late 1970s, many people were concerned that the new ethos was merely one of “self-involvement. The consumption-oriented life-style of immediate gratification soon gave rise to President Carter’s notorious 1979 “Crisis of Confidence” speech, which warned against judging success on material wealth rather than intrinsic human qualities of character and morality.

Meanwhile, the nation kept building more shopping malls, and imagined worlds futuristic (Logan’s Run) and apocalyptic (Dawn of the Dead) set at these new shrines to materialism. he 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers remake deals explicitly with this notion too, of the idea of people “moving in and out of relationships too fast” because they wanted to be happy and fulfilled, all the time.

But in a way, this is what Close Encounters concerns as well. Roy Neary helps himself, finally, to achieve his “dream,” even if his family can’t share in that dream. He gets what he wants — to go with the benevolent aliens to the stars — and in the late 1970s, this result is what qualified as a happy ending.

In his text How Fundamentalism Betrays Christianity (Three Rivers Press, 1997, page 291) author Bruce Bawer wrote of Close Encounters of the Third Kind that “salvation, meaning, and transcendence come down from the Heavens in a spaceship.” The question to ponder today involves the brand of salvation and transcendence.

Is it a spiritual reckoning, or a secular one that the alien spaceship brings with it?

It is a testament to Spielberg’s skill, perhaps, as a filmmaker and storyteller, that Close Encounters can be interpreted through two such opposite lenses or world-views.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.