Preparing a Warp from Nylon Yarn, British Nylon Spinners, Pontypool, Wales, 1964.

Maurice Broomfield (1916-2010) photographed British industry in the 1950s and 1960s, an era Harold Wilson called the “white heat” of rapid technological transition. Born in Draycott, Derbyshire, England, Broomfield began his working career age 15 as a lathe operator for Rolls-Royce, back when the UK was the world’s workshop. He studied art at evening classes, where he sensibly ignored the advice of his photography teacher. Broomfield was largely self-taught.

In 1964, Broomfield’s work represented the UK at the World’s Fair in New York. There is a thread of propaganda to his work.“Factory work reduces the essence of the meaning of life,” he said. “I had a responsibility towards the company. I wasn’t a news photographer.”

That same year he took the fabulous photo you see above of a woman on the production line at British Nylon Spinners, Pontypool, Wales. Who is she? And was she doing her job? “Maurice would treat the factories as film sets,” says his son Nick, “putting attractive people in shot, even if they weren’t the ones charged with the task he was photographing, and ruthlessly recrafting backdrops to suit his own perfectionist vision.”

And the staging? “I love lighting,” said Maurice. “It changes everything. It creates moods; it’s like a painting material. Take two people assembling a bearing in a corrugated iron shack. If I show them in a complete environment, that is not going to do any credit to the product they are making. So I would overlight the subject and underlight the background so that it went pitch black. The pictures were not about what I left in but what I left out.”

British Nylon Spinners (BNS) was founded by ICI in 1940 in partnership with Courtaulds, the leading suppliers of viscose rayon. This was a marriage of science and textiles. Nylon was needed to make parachutes. Japan’s entry into the war in December 1941 cut off supplies of silk. And Nylon, the man-made material invented by Wallace H Carothers that “flouts Solomon“, an “entirely new arrangement of matter under the sun” was the solution. In March 1948 BNS moved from plants in Coventry and Stowmarket to a new, purpose-built site in Mamhilad, Pontypool, South Wales. At its height as many as 10,000 people worked at the complex.

BNS ceased to exist in 1964, when ICI purchased Courtaulds’ stake after a failed takeover attempt. ICI sold its interest in nylon to the American patent-holder, DuPont, in 1992. The last nylon workers in Pontypool were made redundant when DuPont moved production to Turkey. The factory closed in 2003.

Broomfield saw factories as stage sets

Broomfield’s images are sensational. But what was life at the BNS factory really like? Sheila Hughes got a job at the factory in 1953. She stayed until 1967. Born on July 2 1937, Sheila told her story in November 2013.

I was offered a chance of a job at the nylon as it was, and there were about four or five thousand people working at the nylon then, so it was a good opportunity and they offered to take me in and train me as a shorthand typist, because at that time they had their own typing school, I think there were about eight of us, and we were to do, I’m trying to think how long it was, I don’t know if it was a two or a three month course, which was very intensive to learn shorthand typing, office management, and things like that. Unfortunately I was a shorthand typist who couldn’t read my shorthand back so I was asked if I would like to move to another department…

Sheila moved to a section that was “extremely noisy”. There were no ear protectors. Sheila and her colleagues learned to lip-read. She earned £3 a week, rising to £12 by the time of her departure. Her manager was Rita Crosby and there was a supervisor named Mary Simmonds. Is that one of them in the photo?

Staff of Production Control at BNS – Julie Moore far right standing

Food was plentiful. Dorothy rolled a trolley come round with coffee in one urn and tea in another. She offered filled rolls in the morning and cakes in the afternoon. “The canteen was excellent,” says Sheila. “There were different grades of restaurant. I mean, we went to the worker’s canteen, because we were in main plant, but if you worked in the offices there was sort of a higher grade where you had waitress service. I did go there occasionally when I got promoted. And so you had waitress service there, which was very nice.”

Film actresses Honor Blackman and Lana Morris run their fingers through the new nylon stockings becoming available in the UK, 1949.

Sheila:

“When I started there, there was no admin, there was no textile development department, there was no research office block, it was all sort of put into a pilot plant, then there was a big gap and then there was the main plant. And I ended up working in the main plant. I went from the typing pool, and I went into the physical test lab, where we used to test the different strengths and things of the nylon, as it came off the machines to make sure that the machines were working properly. It was very interesting…”

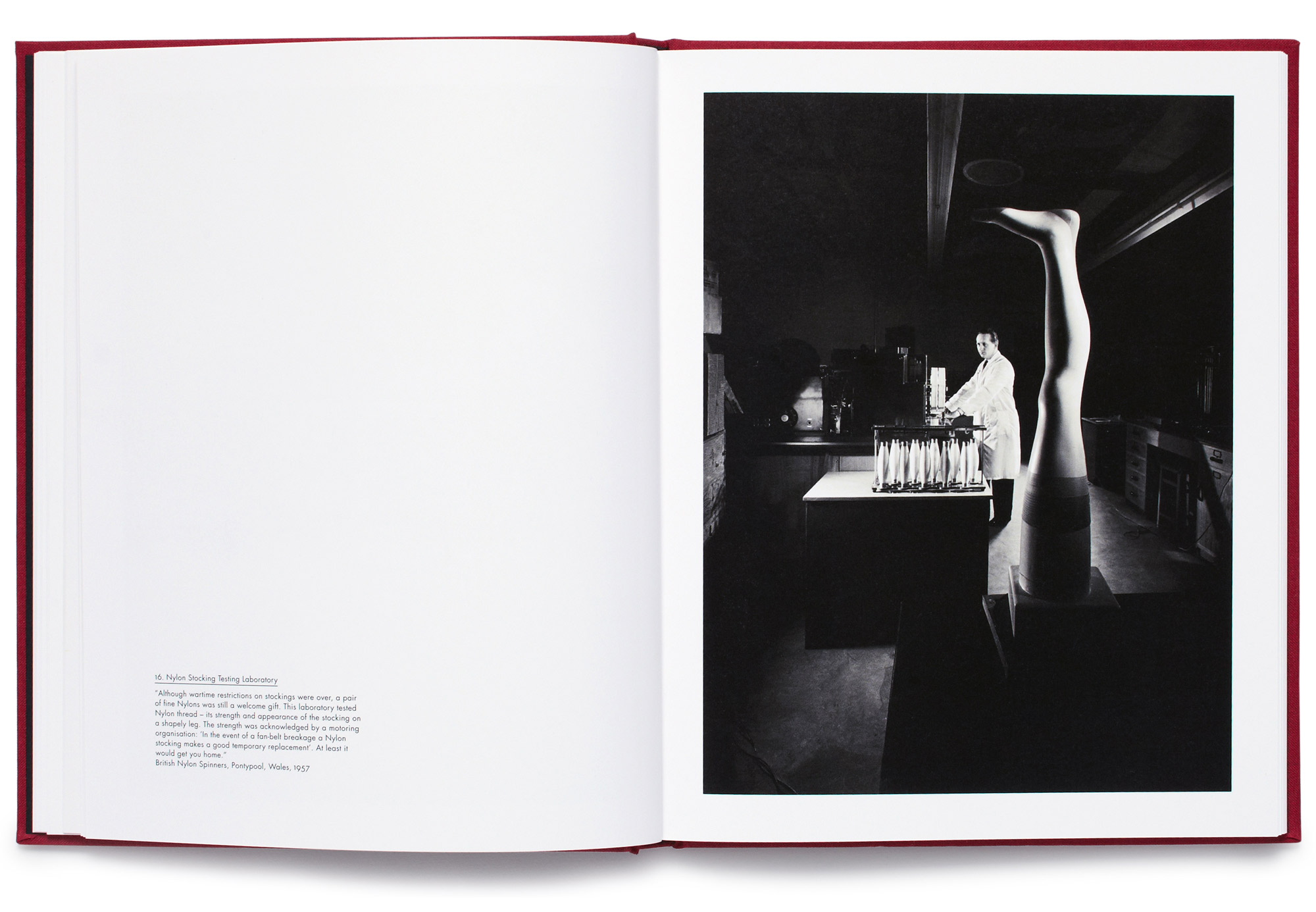

A photo of lab staff

by Audrey Gray, who worked there

Life revolved around the factory:

“It was one long social life! There were dances and we had, when I started there they had a small clubhouse, 1960-ish they opened a big clubhouse the other side of the road, the other side of the main road, which had one of the biggest ballrooms in South Wales I think. It was huge. And it was a beautiful building. It had all sorts of places downstairs, there was a rifle range and there was, they used to have judo lessons, we used to have judo classes there, judo club, they had the ballroom which was a sprung floor which was wonderful, a huge stage, grand piano, restaurant there, a couple of bars, and there was always something going on there.

“Bill [her husband who also worked there] and I used to go the, they used to have, music and drama, no music and film, and you’d get offbeat films. We saw The Wild Ones there before it was issued. With Marlon Brando. It wasn’t allowed to be out in the cinema, but we saw it there. And we went to see John Ogden, pianist; we went to see Campoli, the violinist; we went to see Leon Goossens the oboe player. They had big orchestras there, my dad was a house band there for a long time, who sort of played when the big bands wanted a break, dad would take his, you know, his band was there. And they had people like Ted Heath, Joe Loss, Felix Mendelssohn, Ken Cooper, you know, they had all the big bands there. Big companies come down from London. You know, it was a very organised, a very well-run thing. Christmas parties… there was always something going on, yeah the parties were good.”

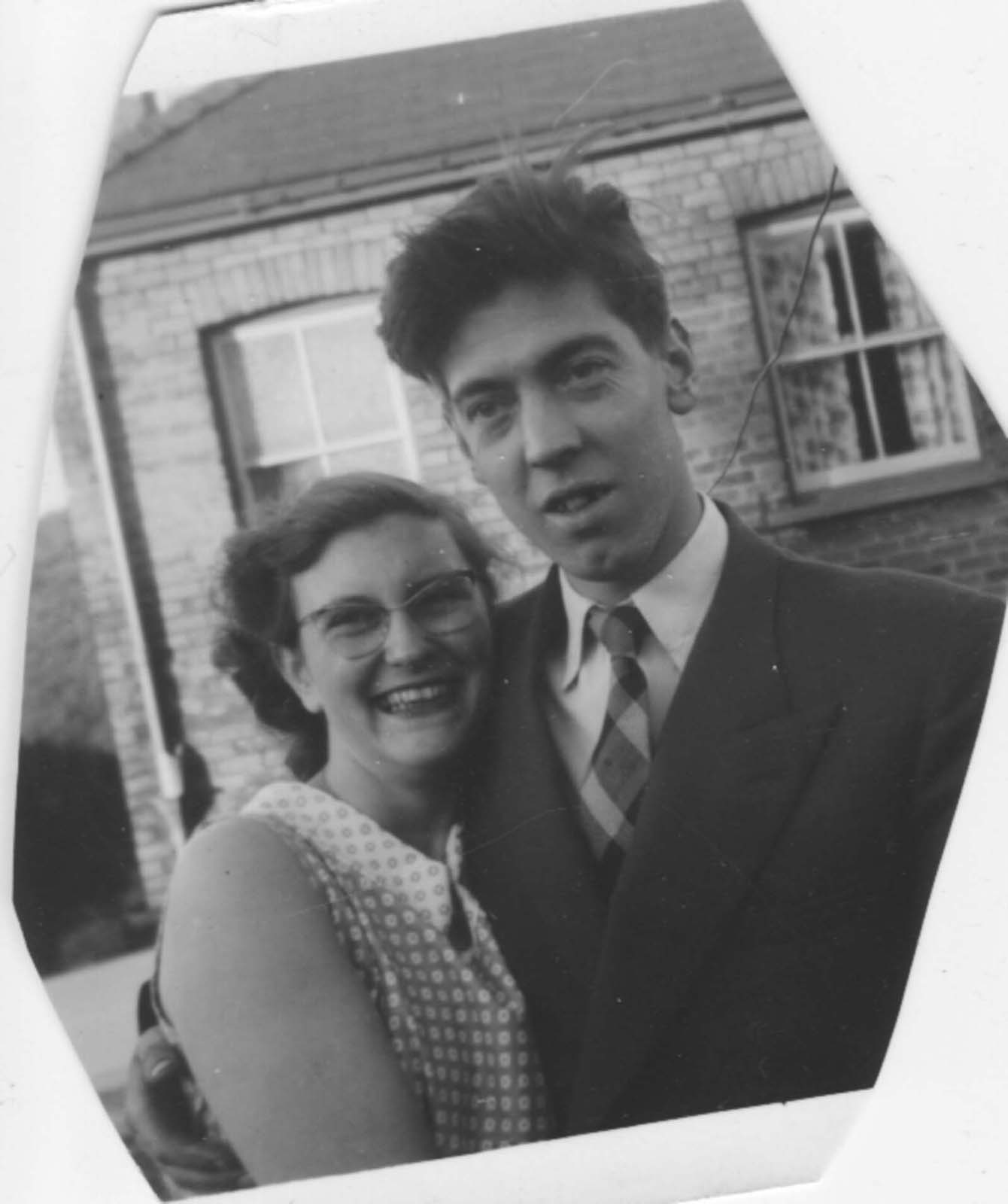

Sheila and her husband (via)

You could read about events and more in Signpost, the weekly factory newspaper:

I think it was a penny or something or two pence, it wasn’t very expensive anyway, coppers. And, but it gave you what was going on in the factory, who’d got married, who’d left to have babies, and you know things like that, and there was usually a photograph of the section that they were being presented with baby clothes or wedding presents and things like that. And who’d won the football matches, and the hockey team and the cricket team and the rugby team, you know, what was

generally going on in the factory

A selection from the V&A’s archive of Broomfield’s photographs are on display at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

Sheila’s story via Women’s Archive of Wales

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.